Gentrifying Lisbon Downtown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WILLIE DOHERTY B

WILLIE DOHERTY b. 1959, Derry, Northern Ireland Lives and works in Derry EDUCATION 1978-81 BA Hons Degree in Sculpture, Ulster Polytechnic, York Street 1977-78 Foundation Course, Ulster Polytechnic, Jordanstown FORTHCOMING & CURRENT EXHIBITIONS 2020 ENDLESS, Kerlin Gallery, online viewing room, (27 May - 16 June 2020), (solo) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Remains, Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Ireland Inquieta, Galeria Moises Perez de Albeniz, Madrid, Spain 2017 Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Switzerland Remains, Art Sonje Center, Seoul, South Korea No Return, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA Loose Ends, Matt’s Gallery, London, UK 2016 Passage, Alexander and Bonin, New York Lydney Park Estate, Gloucestershire, presented by Matt’s Gallery + BLACKROCK Loose Ends, Regional Centre, Letterkenny; Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland Home, Villa Merkel, Germany 2015 Again and Again, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, CAM, Lisbon Panopticon, Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), Salt Lake City 2014 The Amnesiac and other recent video and photographic works, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA UNSEEN, Museum De Pont, Tilburg The Amnesiac, Galería Moisés Pérez de Albéniz, Madrid REMAINS, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2013 UNSEEN, City Factory Gallery, Derry Secretion, Neue Galerie, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel Secretion, The Annex, IMMA, Dublin Without Trace, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich 2012 Secretion, Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen LAPSE, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin Photo/text/85/92, Matts Gallery, London One Place Twice, -

GROWING INTERNATIONAL SALES Global Segmentation Toolkit Using Segmentation to Win International Sales CONTENTS

GROWING INTERNATIONAL SALES Global Segmentation Toolkit Using segmentation to win international sales CONTENTS − Introduction − Culturally Curious − Social Energisers − Great Escapers − Understanding experiential tourism − The experience wheel − The 5 stage digital consumer journey − Direct and indirect sales channels − Overview − Air and ferry routes − Snapshot of the market − 5 steps to developing your sales plan − Overseas sales action plan template − Fáilte Ireland − Tourism Ireland INTRODUCTION In 2013 Irish tourism saw a significant and well deserved growth in overseas visitor numbers with many markets now back or close to peak performance levels. Overall growth of 7.2% in 2013 was reflected in an increase from Great Britain (GB) of +5.6%, the United States (US) +14.5%, Germany + 7.7% and France + 9.4%. For the first nine months of 2013, corresponding overseas revenue grew by +13% and holidaymakers by +13%. With growth of +11% between December 2013 and February 2014, the positive start to 2014 is reflected in all the main source markets; visitors from North America (US & Canada) have increased by +17%; GB +14%; Germany +16% and France + 5%. Tourism Ireland’s target for 2014 is 8.2m overseas visitors, an increase of 1 million over 2013. While the trading environment in most source markets remains challenging there are positive indicators. To secure this growth Ireland must win additional market share in the main markets and in a determined effort to do this, the tourism agencies on the island of Ireland are jointly implementing a new, evidence-based consumer global segmentation model. This model provides new, unique insights about the key consumer segments; their motivations, the kinds of experiences they will buy, associated market differentiators and the key channel intermediaries they use. -

What Is Cool Edit Pro LE?

Getting Started Thank you for purchasing the Roland ED UA-30 USB Audio Interface. This manual tells how to set up the UA-30, and explains basic operation. To avoid problems and enjoy optimal performance, please perform the setup correctly as described in this manual. Before using this unit, carefully read the sections entitled: “USING THE UNIT SAFELY” and “IMPORTANT NOTES” ( P.2, P.4). These sections provide important information concerning the proper operation of the unit. Additionally, in order to feel assured that you have gained a good grasp of every feature provided by your new unit, Getting Started should be read in its entirety. The manual should be saved and kept on hand as a convenient reference. Copyright © 1999 ROLAND CORPORATION All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ROLAND CORPORATION. Used for instructions intended to alert The symbol alerts the user to important instructions the user to the risk of death or severe or warnings.The specific meaning of the symbol is injury should the unit be used determined by the design contained within the improperly. triangle. In the case of the symbol at left, it is used for general cautions, warnings, or alerts to danger. Used for instructions intended to alert the user to the risk of injury or material The symbol alerts the user to items that must never be carried out (are forbidden). The specific thing that damage should the unit be used must not be done is indicated by the design contained improperly. -

Predeparture Information Guide

Barcelona Summer - Internship Program Predeparture Information Congratulations on your decision to intern this summer! We have no doubt that it will be a life-changing adventure. We're glad to have you with us. Here you will find more details about your program and find out what you need to do next. You should also begin filling out your online predeparture forms that are accessible in your MyIESabroad account. Feeling lost? Your IES Internships Advisor is here to help. Just call 800.995.2300 or email [email protected]. How will this experience redefine you? We can't wait to find out! Page 1 Table Of Contents Getting Started ................................................................. 3 Plan Travel ........................................................................ 5 Passport & Visa ................................................................ 5 Travel Dates .................................................................... 7 Arrival .............................................................................. 9 My Program .................................................................... 11 Packing ......................................................................... 11 Housing ......................................................................... 13 Academics ..................................................................... 17 Tuition & Financial Aid .................................................... 21 Field Trips ...................................................................... 26 Health -

SEAN SCULLY B

SEAN SCULLY b. 1945, Dublin Lives and works in New York & Mooseurach, Germany CURRENT & FORTHCOMING EXHIBITIONS 2021 Standing on the Land, Pilane Sculpture Park, Klövedal, Sweden (Solo, 15 May – 26 September) The Shape of Ideas, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX, USA (Solo, June – October) London Calling. British art today. From David Hockney to Idris Khan, Fundación Bancaja, Valencia (Group, 17 June – 17 October) From the Real: Liliane Tomasko & Sean Scully, Newlands House Gallery, Petworth House and Park, Petworth, UK (24 July – 10 October) Masterpieces in Miniature: The 2021 Model Art Gallery, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, UK (Group, 26 June – Spring 2022) Passenger, Benaki Museum, Athens, Greece (Solo, 22 November) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Passenger – a retrospective, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest, Hungary Eleuthera, Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin Entre ciel et terre, Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, France Overlay, Kewenig, Berlin, Germany Sean Scully: Wall Big And Small, Lisson Gallery, East Hampton, USA 2020 Insideoutside, Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden, Wuppertal, Germany Opulent Ascension, LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster, Germany Aeternum, Forum Paracelsus, St Moritz, Switzerland Sean Scully. Early Prints, Galerie Klüser, Münich, Germany 2019 Eleuthera, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo, Málaga, Spain Long Night, Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese, Italy Landline, The Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, USA Sean Scully. Celtique Picasso House,Château de Boisgeloup, Gisros, France PAN, Lisson Gallery, NYC, USA Sean Scully: -

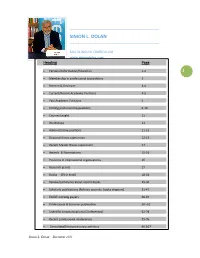

Simon L. Dolan

SIMON L. DOLAN MULTILINGUAL CURRICULUM www.simondolan.com Heading Page • Personal Information/Education 1-2 1 • Membership in professional associations 3 • Referee & Reviewer Content of this document 3-4 • Current/Recent Academic Positions 4-5 • Past Academic Positions 5 • Visiting professorship positions 6-10 • Courses taught 11 • Workshops 11 • Administrative positions 11-12 • Doctoral thesis supervision 12-13 • Recent Master thesis supervision 14 • Awards & Nominations 15-16 • Positions in international organizations 16 • Research grants 17 • Books (59 in total) 18-28 • Review/comments about recent books 29-30 • Scholarly publications (Referee journals, books chapters) 31-47 • ESADE working papers 48-49 • Professional & Business publication 50--61 • Scientific communications (Conferences) 62-78 • Recent professional conferences 79-95 • Consulting/Enterpreneursip activities 96-107 Simon L. Dolan: December 2015 PERSONAL INFORMATION Simon L. Dolan LANGUAGES Proficient - English, French, Spanish, Hebrew Functional - Polish, German. 2 CURRENT ADDRESS OFFICE ESADE BUSINESS SCHOOL Future of Work Chr http://www.esade.edu/research-webs/eng/fwc ESADE St. Cugat - CREAPOLIS Campus Avenida de Torreblanca, 59, Suite 409 08172 Sant Cugat del Vallés Tel: +34 93 2806162 ext. 2483 Fax: +34 93 2048105 Email: [email protected] Research gate profile: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Simon_Dolan/ EDUCATION Ph.D. Carlson Graduate School of Management, Industrial Relations Centre The University of Minnesota (1973-1977) Major: Organizational Psychology/Behaviour Minor: Staffing, Training & Development M.A. University of Minnesota (1975-1976) (1976) Major: IR/Human Resource Management Minor: Organizational Psychology M.A. (ABD) Tel Aviv University, Department of (1971-1973) Labor Studies Major: HRM M.Sc. (ABD) Tel Aviv University, Recanati Graduate School of Business Administration Major: Organizational Behavior B.A. -

Fashion and Postcolonial Critique

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 22 Fashion and Postcolonial Critique Elke Gaugele Monica Titton (Eds.) Fashion and Postcolonial Critique Fashion and Postcolonial Critique Elke Gaugele Monica Titton (Eds.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) Volume 22 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present the latest volume in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna’s publication series. The series, published in cooperation with our highly committed partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contemporary thought about art practices and theories. The volumes comprise contributions on subjects that form the focus of discourse in art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is published in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the academy. Authors of high international repute are invited to make contributions that deal with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institute-specific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. All books in the series undergo a single blind peer review. International reviewers, whose identities are not disclosed to the editors of the volumes, give an in-depth analysis and evaluation for each essay. The editors then rework the texts, taking into consideration the suggestions and feedback of the reviewers who, in a second step, make further comments on the revised essays. -

TONY MATELLI Born 1971 in Chicago Lives and Works in Brooklyn

TONY MATELLI Born 1971 in Chicago Lives and works in Brooklyn EDUCATION 1995 MFA, Cranbrook Academy of Art, MI 1993 BFA, Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design, WI 1991 Alliance of Independent Colleges of Art-Independent Study, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 White Flag Projects, St. Louis, MO Tony Matelli: A Human Echo, Bergen, Kunstmuseum, Bergen, Norway The Green Gallery, Milwaukee, WI 2012 Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm Tony Matelli: A Human Echo, ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Aarhus, Denmark Windows, Walls and Mirrors, Leo Koenig Inc., New York 2011 Falkenrot Preis 2011: Tony Matelli, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin (cat.) 2010 The Constant Now, Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm Tony Matelli: Mirror Paintings, Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm Mise en Abyme, Stephane Simoens Contemporary Fine Art, Knokke, Belgium 2009 The Green Gallery East, Milwaukee, WI The Idiot, Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Moscow Life and Times, Galerie Charlotte Moser, Geneva Abandon, Palais de Tokyo, Paris 2008 Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Moscow (cat.) Uppsala Konstmuseum, Uppsala, Sweden (cat.) The Old Me, Leo Koenig Inc., New York 2007 New Work, Leo Koenig Inc., New York 2006 Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm Galerie Charlotte Moser, Geneva Abandon, Centre d’Arte Santa Monica, Barcelona 2005 Fucked, Emmanuel Perrotin Gallery, Paris 2004 Abandon, Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna (cat.) Fucked and The Oracle, Kunstraum Dornbirn, Dornbirn, Austria (cat.) 2003 Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm Sies + Höke Gallery, Düsseldorf 2002 Emmanuel Perrotin Gallery, Paris Gian Enzo Sperone, Rome Sperone Jr., Rome -

Emergence and Sustainability of International Residency

ARTISTS RESIDENCIES THROUGH THE PRISM OF TWO CURRENT ISSUES : - EMERGENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY OF INTERNATIONAL RESIDENCY PROGRAMMES - LOCAL DEVELOPMENT THROUGH RESIDENCY PROJECTS LED BY PRIVATE ENTITIES, IN CLOSE PARTNERSHIP WITH PUBLIC ORGANISATIONS October 22-23, 2020 An event organised by Arts en résidence – National network In collaboration with the Institut français With the support of the French Ministry of Culture -Direction générale de la création artistique (DGCA), and Le Carreau du Temple. ARTS EN RÉSIDENCE — NATIONAL NETWORK 2/7 EDITORIAL Originally planned in March 2020 and postponed because of the pandemic, Reflecting Residencies will be taking place in a world shaken by the Covid-19 crisis. In this context, collaborations, exchange of ideas and international mobility will take a new meaning and this symposium will be the time to assert their necessity. We decided to maintain our invitation to European partici- pants, to produce videos on several international projects and to propose our Professional Workshops in a digital format. This October 2-day conference will be the key moment of a series of satelite events that will introduce and extend its themes and reach. From the very beginning, the Institut français wished to In celebration of its ten-year anniversary, Arts en join forces with Arts en résidence – Réseau national and support Résidence has organised the international symposium the Reflecting residencies symposium, which was initially sup- Reflecting Residencies, the first event of its kind dedicated posed to take place in March 2020. The Covid-19 crisis reminded entirely to the subject of the artist residency. us, on the other hand, how much the cultural eco-system, and in As a national network and federation, Arts en Résidence particular residency programmes, were linked to a crucial com- gathers no fewer than 33 structures from across the whole of mon good: freedom of movement. -

Download Artist CV

PAUL WINSTANLEY b. 1954, Manchester Lives and works in London EDUCATION 1991-1992 Churchill College Cambridge / Kettle's Yard Artist in Residence 1976-1978 Slade School of Fine Art, Higher Degree in Fine Art 1973-1976 Cardiff College of Art, BA (Hons) 1st Class 1972-1973 Lanchester Polytechnic, Coventry SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 After the War the Renaissance, 1301PE, Los Angeles, USA 2019 Altered States, Vera Munro Gallery, Hamburg, Germany 2018 Alan Cristea, London, UK Pilar Serra, Madrid, Spain 2017 Faith After Saenredam and Other Paintings Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland 2016 Art School: New Prints and Panel Paintings, Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK 2015 Art School, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York 2014 Art School, 1301PE, Los Angeles 2013 Art School, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin Art School, Vera Munro, Hamburg 2012 Red T Shirt Grey, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London 2011 Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York City, NY 2010 Everybody Thinks This is Nowhere, Alan Cristea Gallery, London 130 IPE, Los Angeles 2009 The Gun Emplacement, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin Lux, Vera Munro Gallery, Hamburg 2008 Threshold, Artspace, Auckland, N.Z. Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York 2007 Republic, 1301PE, Los Angeles 2006 Vera Munro, Hamburg 2005 Homeland, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 1301PE, Los Angeles 2004 Gallery Vera Munro, Hamburg New Art Centre, Roche Court, Salisbury 2003 Maureen Paley, London 2002 Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 1301PE, Los Angeles 2000 Maureen Paley, London Nostalgia, Galerie Andreas Binder, Munich Studies, 1301PE, Los Angeles 1999 Institute, Galerie Nathalie -

Getting Started

Getting Started Thank you for purchasing the Roland ED UA-30 USB Audio Interface. This manual tells how to set up the UA-30, and explains basic operation. To avoid problems and enjoy optimal performance, please perform the setup correctly as described in this manual. Before using this unit, carefully read the sections entitled: “USING THE UNIT SAFELY” and “IMPORTANT NOTES” ( P.2, P.4). These sections provide important information concerning the proper operation of the unit. Additionally, in order to feel assured that you have gained a good grasp of every feature provided by your new unit, Getting Started should be read in its entirety. The manual should be saved and kept on hand as a convenient reference. Copyright © 1999 ROLAND CORPORATION All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ROLAND CORPORATION. Used for instructions intended to alert The symbol alerts the user to important instructions the user to the risk of death or severe or warnings.The specific meaning of the symbol is injury should the unit be used determined by the design contained within the improperly. triangle. In the case of the symbol at left, it is used for general cautions, warnings, or alerts to danger. Used for instructions intended to alert the user to the risk of injury or material The symbol alerts the user to items that must never be carried out (are forbidden). The specific thing that damage should the unit be used must not be done is indicated by the design contained improperly. -

124 Alumni Magazine

124 ALUMNI MAGAZINE January-March 2012 www.iese.edu Antonio Dávila Pascual Berrone Guido Stein Michel Camdessus Hans Ulrich Maerki The Drivers Stepping Off the Politics of Why Europe Must Wanted: Bold New of Progress Money-Go-Round The Revolving Door Return to Basics Breed of Leaders Smarter computing builds a Smarter Planet: 1 in a Series Smarter comes to computing. Today, everything computes. Intelligence has been infused into Tuned to the task: Generic computing stacks are no longer up things no one would recognize as computers: appliances, cars, to the job – because today there are fewer and fewer generic roadways, clothes, even rivers and cornfi elds. This is the daily reality jobs. Transaction processing, with thousands of online users, is of an instrumented, interconnected and intelligent world – a Smarter different from business analytics, with multiple data types and Planet – which IBM began chronicling nearly three years ago. complex queries, which is different from the need to integrate content, people and work flows in a company’s processes. Realizing its promise, however, will require more than infusing That’s why leaders are looking for more than high-performance computation into the world. We also have to make computing technology. They are moving to architectures optimized for itself smarter. specific purposes, and built around their own deep domain Wait, isn’t computing smart, by definition? Without question, knowledge – in healthcare, retail, energy, science and more. remarkable levels of computer intelligence are being invented This workload-specific approach integrates uniquely tuned – such as Watson, the IBM system that defeated the two all-time software and hardware – everything from the applications to champions on the TV quiz show, Jeopardy! But organizations’ the chips themselves.