From Homer to Redi. Some Historical Notes About the Problem of Necrophagous Blowflies’ Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

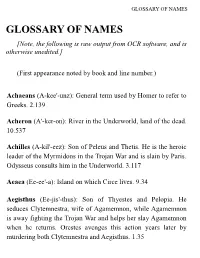

Odyssey Glossary of Names

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction Trojan Cycle: Cypria Iliad (Synopsis) Aethiopis Little Iliad Sack of Ilium Returns Odyssey (Synopsis) Telegony Other works on the Trojan War Bibliography Introduction and Definition of terms The so called Epic Cycle is sometimes referred to with the term Epic Fragments since just fragments is all that remain of them. Some of these fragments contain details about the Theban wars (the war of the SEVEN and that of the EPIGONI), others about the prowesses of Heracles 1 and Theseus, others about the origin of the gods, and still others about events related to the Trojan War. The latter, called Trojan Cycle, narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium ), and after the war (Returns, and Telegony). The term epic (derived from Greek épos = word, song) is generally applied to narrative poems which describe the deeds of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction that periodically and frequently affects mankind. This kind of poetry was composed in early times, being chanted by minstrels during the 'Dark Ages'—before 800 BC—and later written down during the Archaic period— from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Greek (and therefore "Western") literature, and precedes lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, mythography, etc. -

The Frog in Taffeta Pants

Evolutionary Anthropology 13:5–10 (2004) CROTCHETS & QUIDDITIES The Frog in Taffeta Pants KENNETH WEISS What is the magic that makes dead flesh fly? himself gave up on the preformation view). These various intuitions arise natu- Where does a new life come from? manded explanation. There was no rally, if sometimes fancifully. The nat- Before there were microscopes, and compelling reason to think that what uralist Henry Bates observed that the before the cell theory, this was not a one needed to find was too small to natives in the village of Aveyros, up trivial question. Centuries of answers see. Aristotle hypothesized epigenesis, the Tapajos tributary to the Amazon, were pure guesswork by today’s stan- a kind of spontaneous generation of believed the fire ants, that plagued dards, but they had deep implications life from the required materials (pro- them horribly, sprang up from the for the understanding of life. The vided in the egg), that systematic ob- blood of slaughtered victims of the re- 5 phrase spontaneous generation has servation suggested coalesced into a bellion of 1835–1836 in Brazil. In gone out of our vocabulary except as chick. Such notions persisted for cen- fact, Greek mythology is full of beings an historical relic, reflecting a total turies into what we will see was the spontaneously arising—snakes from success of two centuries of biological critical 17th century, when the follow- Medusa’s blood, Aphrodite from sea- research.1 The realization that a new ing alchemist’s recipe was offered for foam, and others. Even when the organism is always generated from the production of mice:3,4 mix sweaty truth is known, we can be similarly one or more cells shed by parents ex- underwear and wheat husks; store in impressed with the phenomena of plained how something could arise open-mouthed jar for 21 days; the generation. -

History and Scope of Microbiology the Story of Invisible Organisms

A study material for M.Sc. Biochemistry (Semester: IV) Students on the topic (EC-1; Unit I) History and Scope of Microbiology The story of invisible organisms Dr. Reena Mohanka Professor & Head Department of Biochemistry Patna University Mob. No.:- +91-9334088879 E. Mail: [email protected] MICROBIOLOGY 1. WHAT IS A MICROBIOLOGY? Micro means very small and biology is the study of living things, so microbiology is the study of very small living things normally too small that are usually unable to be viewed with the naked eye. Need a microscope to see them Virus - 10 →1000 nanometers Bacteria - 0.1 → 5 micrometers (Human eye ) can see 0.1 mm to 1 mm Microbiology has become an umbrella term that encompasses many sub disciplines or fields of study. These include: - Bacteriology: The study of bacteria - Mycology: Fungi - Protozoology: Protozoa - Phycology: Algae - Parasitology: Parasites - Virology: Viruses WHAT IS THE NEED TO STUDY MICROBIOLOGY • Genetic engineering • Recycling sewage • Bioremediation: use microbes to remove toxins (oil spills) • Use of microbes to control crop pests • Maintain balance of environment (microbial ecology) • Basis of food chain • Nitrogen fixation • Manufacture of food and drink • Photosynthesis: Microbes are involved in photosynthesis and accounts for >50% of earth’s oxygen History of Microbiology Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) (Dutch Scientist) • The credit of discovery of microbial world goes to Anton van Leeuwenhoek. He made careful observations of microscopic organisms, which he called animalcules (1670s). • Antoni van Leeuwenhoek described live microorganisms that he observed in teeth scrapings and rain water. • Major contributions to the development of microbiology was the invention of the microscope (50-300X magnification) by Anton von Leuwenhoek and the implementation of the scientific method. -

2. Scientific Inquiry-S

Scientific Inquiry What do scientists do? Why? Science is a unique way of learning about the natural world. Scientists work hard to explain events, living organisms, and changes we see around us every day. Model 1 depicts typical activities or stages scientists engage in when conducting their work. The design of the model shows how various steps in scientific inquiry are connected to one another. None of the activities stands alone—they are all interdependent. Model 1 – Scientific Inquiry Observe Communicate Define the with the wider problem community Form a Reflect study on the question findings Questions Research Analyze the problem the results State the Experiment expectations and gather (hypothesis) data Scientific Inquiry 1 1. What is the central theme of all scientific inquiry as shown in Model 1? 2. What are the nine activities that scientists engage in as part of scientific inquiry? 3. Which of the activities would require a scientist to make some observations? 4. Which of the steps would require a scientist to gather data? 5. Considering the activity described as “communicating with the wider community,” in what ways might a scientist communicate? 6. Remembering that scientists often work in teams, which activities would require a scientist to communicate with others? 7. Given your responses to Questions 1–6, do you think these activities must be carried out in a specific order or can multiple activities be carried out at the same time? Justify your response by giving examples to support your answer. 2 POGIL™ Activities for High School Biology Model 2 – Redi’s Experiment Meat Fly eggs and maggots Fly Solid cover Screen cover Container 1 Container 2 Container 3 The table below represents the ideas the Italian scientist Francesco Redi (1626–1698) might have had as he was carrying out his experiments. -

The Geological Origins of the Oracle at Delphi, Greece1 J.Z

The Geological Origins of the Oracle at Delphi, Greece1 J.Z. DE BOER Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut, USA J.R. HALE College of Arts & Sciences, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, USA ncient authors from Plato to Pausanias geological setting of the sanctuary. According have left descriptions of Delphi’s to a number of Greek and Roman authorities, Aoracle and its mantic sessions. The the women who spoke the prophecies at latter were interpreted as events in which the Delphi sat on a tripod that spanned a cleft Pythia (priestess) placed herself on a tripod over or fissure in the rock within the temple of a cleft (fissure) in the ground below the Apollo Apollo. Vapours rose from this chasm into temple. Here she inhaled a vapour rising from the inner sanctum or adyton, where they the cleft, and became inspired with the power of intoxicated the priestess and inspired her prophecy. French archaeologists who excavated prophecies. The ancient testimonies have the oracle site at the turn of the century reported been challenged during the past half- no evidence of either fissures or gaseous emissions century, as modern archaeologists failed to and concluded that the ancient accounts were locate any cleft or source of vapours within myths. As a result, modern classical scholars the foundations of the ruined temple and and many archaeologists reject the ancient therefore concluded that the ancient sources testimonies concerning the mantic sessions and must have been in error. However, a recent their geological origin. geological study of the sanctuary and adjacent However, the geological conditions at the areas has shown that the preconditions for oracle site do not a priori exclude the early the emission of intoxicating fumes are indeed accounts. -

Section 1–2 How Scientists Work (Pages 8–15)

BIO_ALL IN1_StGd_tese_ch01 8/7/03 5:42 PM Page 181 Name______________________________ Class __________________ Date ______________ Section 1–2 How Scientists Work (pages 8–15) This section explains how scientists test hypotheses. It also describes how a scientific theory develops. Designing an Experiment (pages 8–10) 1. The idea that life can arise from nonliving matter is called spontaneous generation . 2. What was Francesco Redi’s hypothesis about the appearance of maggots? Flies produce maggots. 3. What are variables in an experiment? They are factors that can change. 4. Ideally, how many variables should an experiment test at a time? It should test only one variable at a time. 5. When a variable is kept unchanged in an experiment, it is said to be controlled . 6. What is a controlled experiment? A controlled experiment is an experiment in which one variable is changed while the other variables are controlled. 7. The illustration below shows the beginning of Redi’s experiment. Complete the illustration by showing the outcome. Redi’s Experiment on Spontaneous Generation Uncovered jars Covered jars Several days pass. © Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Maggots appear No maggots appear BIO_ALL IN1_StGd_tese_ch01 8/7/03 5:42 PM Page 182 Name______________________________ Class __________________ Date ______________ 8. Complete the table about variables. VARIABLES Type of Variable Definition Manipulated variable The variable that is deliberately changed in an experiment Responding variable The variable that is observed and changes in response to the manipulated variable 9. In Redi’s experiment, what were the manipulated variable and the responding variable? The manipulated variable was the presence or absence of the gauze covering, and the responding variable was whether maggots appear. -

KA H. Crosthwaite

1 KA A Handbook of Mythology, Sacred Practices, Electrical Phenomena, and their Linguistic Connections in the Ancient Mediterranean World by H. Crosthwaite with an Introduction by Alfred de Grazia Metron Publications Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A. 2 Notes on the printed version of this book: ISBN: 0-940268-25-9 Copyright 1992 by Hugh Crosthwaite All rights reserved Printed in the U.S.A. by Princeton University Printing Services. Composed at Metron Publications. Published by METRON PUBLICATIONS, P.O.BOX 1213, PRINCETON, N.]. 08542, U.S.A. 3 for Shirley, ".....the sweetest flower of all the field," and for Susan Q-CD vol 12: KA, Introduction 4 INTRODUCTION SOME years ago, at my suggestion, Hugh Crosthwaite commenced this major work. Its first pages appeared in the mails as parts of personal letters. He called them notes. They were notes, yes, but like the "toying at the piano keys" of a maestro, they possessed authenticity, reflected a great repertoire, and hit upon original meanings in every direction a tone was struck. The notes began to modulate into cultures and tongues other than the classic Greek as the research continued. I should be remembered, perhaps, for not having said to him, "Please cease to send me your notes and compose instead a proper monograph: thesis, proof, basta." Rather, as the messages kept coming, I redefined for myself, and I hope for hundreds of readers to come, the relation of form to value. The author carries, among other traits characteristic of English scholarship at its best, the famed stubborn empiricism that has so often been the despair of theorists and philosophers such as myself. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Homer's Roads Not Taken

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Homer’s Roads Not Taken Stories and Storytelling in the Iliad and Odyssey A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Craig Morrison Russell 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Homer’s Roads Not Taken Stories and Storytelling in the Iliad and Odyssey by Craig Morrison Russell Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Alex C. Purves, Chair This dissertation is a consideration of how narratives in the Iliad and Odyssey find their shapes. Applying insights from scholars working in the fields of narratology and oral poetics, I consider moments in Homeric epic when characters make stories out of their lives and tell them to each other. My focus is on the concept of “creativity” — the extent to which the poet and his characters create and alter the reality in which they live by controlling the shape of the reality they mould in their storytelling. The first two chapters each examine storytelling by internal characters. In the first chapter I read Achilles’ and Agamemnon’s quarrel as a set of competing attempts to create the authoritative narrative of the situation the Achaeans find themselves in, and Achilles’ retelling of the quarrel to Thetis as part of the move towards the acceptance of his version over that of Agamemnon or even the Homeric Narrator that occurs over the course of the epic. In the second chapter I consider the constant storytelling that [ii ] occurs at the end of the Odyssey as a competition between the families of Odysseus and the suitors to control the narrative that will be created out of Odysseus’s homecoming. -

Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to The

SIMB News News magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology April/May/June 2019 V.69 N.2 • www.simbhq.org Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to the Present :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJΘŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ Impact Factor 3.103 The Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology is an international journal which publishes papers in metabolic engineering & synthetic biology; biocatalysis; fermentation & cell culture; natural products discovery & biosynthesis; bioenergy/biofuels/biochemicals; environmental microbiology; biotechnology methods; applied genomics & systems biotechnology; and food biotechnology & probiotics Editor-in-Chief Ramon Gonzalez, University of South Florida, Tampa FL, USA Editors Special Issue ^LJŶƚŚĞƚŝĐŝŽůŽŐLJ; July 2018 S. Bagley, Michigan Tech, Houghton, MI, USA R. H. Baltz, CognoGen Biotech. Consult., Sarasota, FL, USA Impact Factor 3.500 T. W. Jeffries, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA 3.000 T. D. Leathers, USDA ARS, Peoria, IL, USA 2.500 M. J. López López, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain C. D. Maranas, Pennsylvania State Univ., Univ. Park, PA, USA 2.000 2.505 2.439 2.745 2.810 3.103 S. Park, UNIST, Ulsan, Korea 1.500 J. L. Revuelta, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain 1.000 B. Shen, Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, USA 500 D. K. Solaiman, USDA ARS, Wyndmoor, PA, USA Y. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA E. J. Vandamme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium H. Zhao, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA 10 Most Cited Articles Published in 2016 (Data from Web of Science: October 15, 2018) Senior Author(s) Title Citations L. Katz, R. Baltz Natural product discovery: past, present, and future 103 Genetic manipulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis for improved production in Streptomyces and R. -

The Pythias Excerpted from Secret History of the Witches © 2009 Max Dashu

The Pythias excerpted from Secret History of the Witches © 2009 Max Dashu I count the grains of sand on the beach and measure the sea I understand the speech of the mute and hear the voiceless —Delphic Oracle [Herodotus, I, 47] In the center of the world, a fissure opened from the black depths of Earth, and waters flowed from a spring. The place was called Delphoi (“Womb”). In its cave sanctuary lived a shamanic priestess called the Pythia—Serpent Woman. Her prophetic power came from a she-dragon in the Castalian spring, whose waters had inspirational qualities. She sat on a tripod, breathing vapors that emerged from a deep cleft in the Earth, until she entered trance and prophesied by chanting in verse. The shrine was sacred to the indigenous Aegean earth goddess. The Greeks called her Ge, and later Gaia. Earth was said to have been the first Delphic priestess. [Pindar, fr. 55; Euripides, Iphigenia in Taurus, 1234-83. This idea of Earth as the original oracle and source of prophecy was widespread. The Eumenides play begins with a Pythia intoning, “First in my prayer I call on Earth, primeval prophetess...” [Harrison, 385] Ancient Greek tradition held that there had once been an oracle of Earth at the Gaeion in Olympia, but it had disappeared by the 2nd century. [Pausanias, 10.5.5; Frazer on Apollodorus, note, 10] The oracular cave of Aegira, with its very old wooden image of Broad-bosomed Ge, belonged to Earth too. [Pliny, Natural History 28. 147; Pausanias 7, 25] Entranced priestess dancing with wand, circa 1500 BCE. -

History of Microbiology: Spontaneous Generation Theory

HISTORY OF MICROBIOLOGY: SPONTANEOUS GENERATION THEORY Microbiology often has been defined as the study of organisms and agents too small to be seen clearly by the unaided eye—that is, the study of microorganisms. Because objects less than about one millimeter in diameter cannot be seen clearly and must be examined with a microscope, microbiology is concerned primarily with organisms and agents this small and smaller. Microbial World Microorganisms are everywhere. Almost every natural surface is colonized by microbes (including our skin). Some microorganisms can live quite happily in boiling hot springs, whereas others form complex microbial communities in frozen sea ice. Most microorganisms are harmless to humans. You swallow millions of microbes every day with no ill effects. In fact, we are dependent on microbes to help us digest our food and to protect our bodies from pathogens. Microbes also keep the biosphere running by carrying out essential functions such as decomposition of dead animals and plants. Microbes are the dominant form of life on planet Earth. More than half the biomass on Earth consists of microorganisms, whereas animals constitute only 15% of the mass of living organisms on Earth. This Microbiology course deals with • How and where they live • Their structure • How they derive food and energy • Functions of soil micro flora • Role in nutrient transformation • Relation with plant • Importance in Industries The microorganisms can be divided into two distinct groups based on the nucleus structure: Prokaryotes – The organism lacking true nucleus (membrane enclosed chromosome and nucleolus) and other organelles like mitochondria, golgi body, entoplasmic reticulum etc. are referred as Prokaryotes.