Dissertation Whole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Different Dialects of Arabic Language

e-ISSN : 2347 - 9671, p- ISSN : 2349 - 0187 EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review Vol - 3, Issue- 9, September 2015 Inno Space (SJIF) Impact Factor : 4.618(Morocco) ISI Impact Factor : 1.259 (Dubai, UAE) DIFFERENT DIALECTS OF ARABIC LANGUAGE ABSTRACT ifferent dialects of Arabic language have been an Dattraction of students of linguistics. Many studies have 1 Ali Akbar.P been done in this regard. Arabic language is one of the fastest growing languages in the world. It is the mother tongue of 420 million in people 1 Research scholar, across the world. And it is the official language of 23 countries spread Department of Arabic, over Asia and Africa. Arabic has gained the status of world languages Farook College, recognized by the UN. The economic significance of the region where Calicut, Kerala, Arabic is being spoken makes the language more acceptable in the India world political and economical arena. The geopolitical significance of the region and its language cannot be ignored by the economic super powers and political stakeholders. KEY WORDS: Arabic, Dialect, Moroccan, Egyptian, Gulf, Kabael, world economy, super powers INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION The importance of Arabic language has been Within the non-Gulf Arabic varieties, the largest multiplied with the emergence of globalization process in difference is between the non-Egyptian North African the nineties of the last century thank to the oil reservoirs dialects and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is in the region, because petrol plays an important role in nearly incomprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Algeria. propelling world economy and politics. -

Asmahan Presence and Distinctive Performance Style

A versatile singer renowned for her powerful voice, enchanting stage Asmahan presence and distinctive performance style. Amal Al-Atrash, (1912-1944), better known by her stage name Asmahan, was an exceptional Syrian-Egyptian singer and actor who rose to fame in Egypt in the 1930s and early 1940s. Born into a prominent family, she moved from Syria to Egypt with her mother and siblings due to political unrest. To earn a living, her mother, who had an excellent voice, began singing and playing the oud. She was a source of inspiration for Asmahan and her brother, Farid Al-Atrash, who also became a famous musician. Asmahan, like her mother, demonstrated vocal talent from an early age, and went on to sing songs written by DID YOU KNOW? renowned musicians in some of Egypt’s most important venues. Asmahan collaborated with the great artist Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Asmahan was a versatile singer celebrated singing one of his compositions for for her powerful voice, enchanting stage the Film Yawm Sa’id (Happy Day). presence and distinctive performance style. She was not only skilled in tarab, but she was also incredibly innovative. Her voice was FUN FACT regarded as one of the few in the Arab world at the time able to compete with renowned Asmahan and her brother Farid Al- Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum. Atrash starred in the successful 1941 film Intisar al-Shabab (The Triumph Despite her short life, Asmahan performed of Youth), in which they portray two and recorded several memorable songs young singers looking for fame in Egypt. composed by renowned musicians, including her brother Farid Al-Atrash. -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

Arabic Kinship Terms Revisited: the Rural and Urban Context of North-Western Morocco

Sociolinguistic ISSN: 1750-8649 (print) Studies ISSN: 1750-8657 (online) Article Arabic kinship terms revisited: The rural and urban context of North-Western Morocco Amina Naciri-Azzouz Abstract This article reports on a study that focuses on the different kinship terms collected in several places in north-western Morocco, using elicitation and interviews conducted between March 2014 and June 2015 with several dozens of informants aged between 8 and 80. The analysed data include terms from the urban contexts of the city of Tetouan, but most of them were gathered in rural locations: the small village of Bni Ḥlu (Fahs-Anjra province) and different places throughout the coastal and inland regions of Ghomara (Chefchaouen province). The corpus consists of terms of address, terms of reference and some hypocoristic and affective terms. KEYWORDS: KINSHIP TERMS, TERMS OF ADDRESS, VARIATION, DIALECTOLOGY, MOROCCAN ARABIC (DARIJA) Affiliation University of Zaragoza, Spain email: [email protected] SOLS VOL 12.2 2018 185–208 https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.35639 © 2019, EQUINOX PUBLISHING 186 SOCIOLINGUISTIC STUDIES 1 Introduction The impact of migration ‒ attributable to multiple and diverse factors depending on the period ‒ is clearly noticeable in northern Morocco. Migratory movements from the east to the west, from rural areas to urban centres, as well as to Europe, has resulted in a shifting rural and urban population in this region. Furthermore, issues such as the increasing rate of urbanization and the drop in mortality have altered the social and spatial structure of cities such as Tetouan and Tangiers, where up to the present time some districts are known by the name of the origin of the population who settled down there: e.g. -

Farah Al Qasimi (B

Gallery Guide Farah Al Qasimi (b. 1991, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Artist’s Suggested Reading and Listening List Contemporary Art Emirates; lives and works in Brooklyn and Dubai) works Museum St. Louis in photography, video, and performance. Her recent Selected by Farah Al Qasimi to share insights into her commission with Public Art Fund, Back and Forth Disco, art and ideas. September 3, 2021– was on view at 100 bus shelters in New York City in February 13, 2022 2019–20, and was named one of the best artworks of Reading: the year by The New Yorker. Her work has been featured / The Arab Apocalypse, Etel Adnan, (poetry), The Post-Apollo Press, in exhibitions at Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai; San 2007 Francisco Arts Commission; CCS Bard Galleries at the / Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, Farah Al Qasimi Hessel Museum of Art, New York; Helena Anrather, New and the Duty of Repair, Sarah Schulman, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016 York; The Third Line, Dubai; The List Visual Arts Center / Diving Into The Wreck: Poems 1971-1972, Adrienne Rich, W.W. Everywhere there is splendor at MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Museum of Norton and Company, 1994 (reissue, paperback) Contemporary Art, Toronto; and the Houston Center for / “Eating the other: Desire and resistance,” in Black Looks: Race and Photography. She has participated in residencies at / Representation, bell hooks, South End Press, 1992 the Delfina Foundation, London; Skowhegan School of The Girl Who Fell to Earth: A Memoir, Sophia Al-Maria, Harper Painting and Sculpture, Maine; and is a recipient of the Perennial, 2012 New York NADA Artadia Prize; Aaron Siskind Individual / LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Notion of Family, Dawoud Bey, interview; Photographer’s Fellowship; and this year’s Capricious Laura Wexler and Dennis C. -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

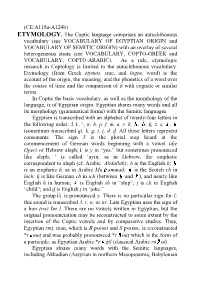

ETYMOLOGY. the Coptic Language Comprises an Autochthonous

(CE:A118a-A124b) ETYMOLOGY. The Coptic language comprises an autochthonous vocabulary (see VOCABULARY OF EGYPTIAN ORIGIN and VOCABULARY OF SEMITIC ORIGIN) with an overlay of several heterogeneous strata (see VOCABULARY, COPTO-GREEK and VOCABULARY, COPTO-ARABIC). As a rule, etymologic research in Coptology is limited to the autochthonous vocabulary. Etymology (from Greek etymos, true, and logos, word) is the account of the origin, the meaning, and the phonetics of a word over the course of time and the comparison of it with cognate or similar terms. In Coptic the basic vocabulary, as well as the morphology of the language, is of Egyptian origin. Egyptian shares many words and all its morphology (grammatical forms) with the Semitic languages. Egyptian is transcribed with an alphabet of twenty-four letters in the following order: 3, „ , ‘, w, b, p, f, m, n, r, h, , , h, z, s, , (sometimes transcribed q), k, g, t, t, d, d. All these letters represent consonants. The sign 3 is the glottal stop heard at the commencement of German words beginning with a vowel (die Oper) or Hebrew aleph; „ is y in “yes,” but sometimes pronounced like aleph; ‘ is called ‘ayin, as in Hebrew, the emphatic correspondent to aleph (cf. Arabic ‘Abdallah); h is the English h; is an emphatic h, as in Arabic Mu ammad; is the Scotch ch in loch; h is like German ch in ich (between and ), and nearly like English h in human; is English sh in “ship”; t is ch in English “child”; and d is English j in ‘joke.” The group „„ is pronounced y. -

Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic

UC Santa Cruz Phonology at Santa Cruz, Volume 7 Title Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0765s94q Author Kramer, Ruth Publication Date 2018-04-10 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic ∗∗∗ Ruth Kramer 1. Introduction One of the most distinctive features of many Afroasiatic languages is nonconcatenative morphology. Instead of attaching an affix directly before or after a root, languages like Modern Hebrew interleave an affix within the segments of a root. An example is in (1). (1) Modern Hebrew gadal ‘he grew’ gidel ‘he raised’ gudal ‘he was raised’ In the mini-paradigm in (1), the discontinuous affixes /a a/, /i e/, and /u a/ are systematically interleaved between the root consonants /g d l/ to indicate perfective aspect, causation and voice, respectively. The consonantal root /g d l/ ‘big’ never surfaces on its own in the language: it must be inflected with some vocalic affix. Additional Afroasiatic languages with nonconcatenative morphology include other Semitic languages like Arabic (McCarthy 1979, 1981; McCarthy and Prince 1990), many Ethiopian Semitic languages (Rose 1997, 2003), and Modern Aramaic (Hoberman 1989), as well as non-Semitic languages like Berber (Dell and Elmedlaoui 1992, Idrissi 2000) and Egyptian (also known as Ancient Egyptian, the autochthonous language of Egypt; Gardiner 1957, Reintges 1994). The nonconcatenative morphology of Afroasiatic languages has come to be known as root and pattern -

Universal Periodic Review Lebanon 2015

UUUNIVERSALUNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW LEBANON 2015 For consideration at the 23 rd session of the UN working group in October 2015 23 March 2015 FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship is an independent international membership organization advocating and defending freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. Freemuse has held Special Consultative Status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) since 2012. PEN International promotes literature and defends freedom of expression. Founded in 1921, our global community of writers have Centres in over 100 countries, including PEN Lebanon Centre. PEN International is a non-political organisation which holds Special Consultative Status at the UN and Associate Status at UNESCO. FREEMUSE and PEN International welcome the opportunity to contribute to the second cycle of the Universal Period Review (UPR) process of Lebanon. This submission examines the protection of freedom of expression and artistic freedoms in Lebanon. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The freedom to create art is increasingly recognized as an important human right under international law. In a June 2013 report, “The Right to Artistic Freedom and Creativity, ” the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Ms. Farida Shaheed, observed that the “vitality of artistic creativity is necessary for the development of vibrant cultures and the functioning of democratic societies. Artistic expressions and creations are an integral part of cultural life, which entails contesting meanings and revisiting culturally inherited ideas and concepts. ”ii 2. The right to artistic freedom and creativity is explicitly guaranteed by international instruments; most importantly, Article 15(3) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), under which state parties to the treaty “undertake to respect the freedom indispensable for . -

Reformed Egyptian

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 19 Number 1 Article 7 2007 Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hamblin, William J. (2007) "Reformed Egyptian," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol19/iss1/7 This Book of Mormon is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Reformed Egyptian Author(s) William J. Hamblin Reference FARMS Review 19/1 (2007): 31–35. ISSN 1550-3194 (print), 2156-8049 (online) Abstract This article discusses the term reformed Egyptian as used in the Book of Mormon. Many critics claim that reformed Egyptian does not exist; however, languages and writing systems inevitably change over time, making the Nephites’ language a reformed version of Egyptian. Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin What Is “Reformed Egyptian”? ritics of the Book of Mormon maintain that there is no language Cknown as “reformed Egyptian.” Those who raise this objec- tion seem to be operating under the false impression that reformed Egyptian is used in the Book of Mormon as a proper name. In fact, the word reformed is used in the Book of Mormon in this context as an adjective, meaning “altered, modified, or changed.” This is made clear by Mormon, who tells us that “the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, [were] handed down and altered by us” and that “none other people knoweth our language” (Mormon 9:32, 34).