Jenny Douglas Dr. Peck Theatre in England in My End Is My

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corpus Christi College the Pelican Record

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LI December 2015 CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LI December 2015 i The Pelican Record Editor: Mark Whittow Design and Printing: Lynx DPM Limited Published by Corpus Christi College, Oxford 2015 Website: http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] The editor would like to thank Rachel Pearson, Julian Reid, Sara Watson and David Wilson. Front cover: The Library, by former artist-in-residence Ceri Allen. By kind permission of Nick Thorn Back cover: Stone pelican in Durham Castle, carved during Richard Fox’s tenure as Bishop of Durham. Photograph by Peter Rhodes ii The Pelican Record CONTENTS President’s Report ................................................................................... 3 President’s Seminar: Casting the Audience Peter Nichols ............................................................................................ 11 Bishop Foxe’s Humanistic Library and the Alchemical Pelican Alexandra Marraccini ................................................................................ 17 Remembrance Day Sermon A sermon delivered by the President on 9 November 2014 ....................... 22 Corpuscle Casualties from the Second World War Harriet Fisher ............................................................................................. 27 A Postgraduate at Corpus Michael Baker ............................................................................................. 34 Law at Corpus Lucia Zedner and Liz Fisher .................................................................... -

Asolo Rep Continues Its 60Th Season with NOISES OFF Directed By

NOISES OFF Page 1 of 7 **FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE** February 25, 2019 Asolo Rep Continues its 60th Season with NOISES OFF Directed by Comedic Broadway Veteran Don Stephenson March 20 - April 20 (SARASOTA, February 25, 2019) — Asolo Rep continues its celebration of 60 years on stage with Tony Award®-winner Michael Frayn's rip-roaringly hilarious play NOISES OFF, one of the most celebrated farces of all time. Directed by comedic Broadway veteran Don Stephenson, NOISES OFF previews March 20 and 21, opens March 22 and runs through April 20 in rotating repertory in the Mertz Theatre, located in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts. A comedy of epic proportions, NOISES OFF has been the laugh-until-you-cry guilty pleasure of audiences for decades. With opening night just hours away, a motley company of actors stumbles through a frantic, final rehearsal of the British sex farce Nothing On, and things could not be going worse. Lines are forgotten, love triangles are unraveling, sardines are flying everywhere, and complete pandemonium ensues. Will the cast pull their act together on stage even if they can't behind the scenes? “With Don Stephenson, an extraordinary comedic actor and director at the helm, this production of NOISES OFF is bound to be one of the funniest theatrical experiences we have ever presented,” said Asolo Rep Producing Artistic Director Michael Donald Edwards. “I urge the Sarasota community to take a break and escape to NOISES OFF, a joyous celebration of the magic of live theatre.” Don Stephenson's directing work includes Titanic (Lincoln Center, MUNY), Broadway Classics (Carnegie Hall),Of Mice and Manhattan (Kennedy Center), A Comedy of Tenors (Paper Mill Playhouse) and more. -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin

PRESS RELEASE IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin LAST CHANCE TO SEE DAVID HARE’S THE MODERATE SOPRANO AS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED WEST END PRODUCTION ENTERS ITS FINAL FIVE WEEKS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE. STARRING OLIVIER AWARD WINNING ROGER ALLAM AND NANCY CARROLL AS GLYNDEBOURNE FOUNDER JOHN CHRISTIE AND HIS WIFE AUDREY MILDMAY. STRICTLY LIMITED RUN MUST END SATURDAY 30 JUNE. Audiences have just five weeks left to see David Hare’s critically acclaimed new play The Moderate Soprano, about the love story at the heart of the foundation of Glyndebourne, directed by Jeremy Herrin and starring Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll. The production enters its final weeks at the Duke of York’s Theatre where it must end a strictly limited season on Saturday 30 June. The previously untold story of an English eccentric, a young soprano and three refugees from Germany who together established Glyndebourne, one of England’s best loved cultural institutions, has garnered public and critical acclaim alike. The production has been embraced by the Christie family who continue to be involved with the running of Glyndebourne, 84 years after its launch. Executive Director Gus Christie attended the West End opening with his family and praised the portrayal of his grandfather John Christie who founded one of the most successful opera houses in the world. First seen in a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, the new production opened in the West End this spring, with Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll reprising their original roles as Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. -

Study Guide for DE Madameby Yukio Mishima SADE Translated from the Japanese by Donald Keene

Study Guide for DE MADAMEBy Yukio Mishima SADE Translated from the Japanese by Donald Keene Written by Sophie Watkiss Edited by Rosie Dalling Rehearsal photography by Marc Brenner Production photography by Johan Persson Supported by The Bay Foundation, Noel Coward Foundation, 1 John Lyon’s Charity and Universal Consolidated Group Contents Section 1: Cast and Creative Team Section 2: An introduction to Yukio Mishima and Japanese theatre The work and life of Yukio Mishima Mishima and Shingeki theatre A chronology of Yukio Mishima’s key stage plays Section 3: MADAME DE SADE – history inspiring art The influence for Mishima’s play The historical figures of Madame de Sade and Madame de Montreuil. Renée’s marriage to the Marquis de Sade Renee’s life as Madame de Sade Easter day, 1768 The path to the destruction of the aristocracy and the French Revolution La Coste Women, power and sexuality in 18th Century France Section 4: MADAME DE SADE in production De Sade through women’s eyes The historical context of the play in performance Renée’s ‘volte-face’ The presence of the Marquis de Sade The duality of human nature Elements of design An interview with Fiona Button (Anne) Section 5: Primary sources, bibliography and endnotes 2 section 1 Cast and Creative Team Cast Frances Barber: Comtesse de Saint-Fond For the Donmar: Insignificance. Theatre includes: King Lear & The Seagull (RSC), Anthony and Cleopatra (Shakespeare’s Globe), Aladdin (Old Vic), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Edinburgh Festival & Gielgud). Film includes: Goal, Photographing Fairies, Prick Up Your Ears. Television includes: Hotel Babylon, Beautiful People, Hustle, The I.T. -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin

PRESS RELEASE IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin LAST CHANCE TO SEE DAVID HARE’S THE MODERATE SOPRANO AS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED WEST END PRODUCTION ENTERS ITS FINAL FIVE WEEKS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE. STARRING OLIVIER AWARD WINNING ROGER ALLAM AND NANCY CARROLL AS GLYNDEBOURNE FOUNDER JOHN CHRISTIE AND HIS WIFE AUDREY MILDMAY. STRICTLY LIMITED RUN MUST END SATURDAY 30 JUNE. Audiences have just five weeks left to see David Hare’s critically acclaimed new play The Moderate Soprano, about the love story at the heart of the foundation of Glyndebourne, directed by Jeremy Herrin and starring Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll. The production enters its final weeks at the Duke of York’s Theatre where it must end a strictly limited season on Saturday 30 June. The previously untold story of an English eccentric, a young soprano and three refugees from Germany who together established Glyndebourne, one of England’s best loved cultural institutions, has garnered public and critical acclaim alike. The production has been embraced by the Christie family who continue to be involved with the running of Glyndebourne, 84 years after its launch. Executive Director Gus Christie attended the West End opening with his family and praised the portrayal of his grandfather John Christie who founded one of the most successful opera houses in the world. First seen in a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, the new production opened in the West End this spring, with Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll reprising their original roles as Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. -

The Seagull Anton Chekhov Adapted by Simon Stephens

THE SEAGULL ANTON CHEKHOV ADAPTED BY SIMON STEPHENS major sponsor & community access partner WELCOME TO THE SEAGULL The artists and staff of Soulpepper and the Young Centre for the Performing Arts acknowledge the original caretakers and storytellers of this land – the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and Wendat First Nation, and The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation who are part of the Anishinaabe Nation. We commit to honouring and celebrating their past, present and future. “All around the world and throughout history, humans have acted out the stories that are significant to them, the stories that are central to their sense of who they are, the stories that have defined their communities, and shaped their societies. When we talk about classical theatre we want to explore what that means from the many perspectives of this city. This is a celebration of our global canon.” – Weyni Mengesha, Soulpepper’s Artistic Director photo by Emma Mcintyre Partners & Supporters James O’Sullivan & Lucie Valée Karrin Powys-Lybbe & Chris von Boetticher Sylvia Soyka Kathleen & Bill Troost 2 CAST & CREATIVE TEAM Cast Ghazal Azarbad Stuart Hughes Gregory Prest Marcia Hugo Boris Oliver Dennis Alex McCooeye Paolo Santalucia Peter Sorin Simeon Konstantin Raquel Duffy Kristen Thomson Sugith Varughese Pauline Irina Leo Hailey Gillis Dan Mousseau Nina Jacob Creative Team Daniel Brooks Matt Rideout Maricris Rivera Director Lead Audio Engineer Producing Assistant Anton Chekhov Weyni Mengesha Megan Woods Playwright Artistic Director Associate Production Manager Thomas Ryder Payne Emma Stenning Corey MacVicar Sound Designer Executive Director Associate Technical Director Frank Cox-O’Connell Tania Senewiratne Nik Murillo Associate Director Executive Producer Marketer Gregory Sinclair Mimi Warshaw Audio Producer Producer Thank You To Michelle Monteith, Daren A. -

David Rabe's Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast with F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perl

David Rabe’s Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast With F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perlman and More t2conline.com/david-rabes-good-for-otto-gets-star-studded-cast-with-f-murray-abraham-ed-harris-mark-linn-baker-amy- madigan-rhea-perlman-and-more/ Suzanna January 30, 2018 Bowling F. Murray Abraham (Barnard), Kate Buddeke (Jane), Laura Esterman (Mrs. Garland), Nancy Giles (Marci), Lily Gladstone (Denise), Ed Harris (Dr. Michaels), Charlotte Hope (Mom), Mark Linn- Baker (Timothy), Amy Madigan (Evangeline), Rileigh McDonald (Frannie), Kenny Mellman (Jerome), Maulik Pancholy (Alex), Rhea Perlman (Nora) and Michael Rabe (Jimmy), will lite up the star in the New York premiere of David Rabe’s Good for Otto. Rhea Perlman took over the role of Nora, after Rosie O’Donnell, became ill. Directed by Scott Elliott, this production will play a limited Off-Broadway engagement February 20 – April 1, with Opening Night on Thursday, March 8 at The Pershing Square Signature Center (The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, 480 West 42nd Street). Through the microcosm of a rural Connecticut mental health center, Tony Award-winning playwright David Rabe conjures a whole American community on the edge. Like their patients and their families, Dr. Michaels (Ed Harris), his colleague Evangeline (Amy Madigan) and the clinic itself teeter between breakdown and survival, wielding dedication and humanity against the cunning, inventive adversary of mental illness, to hold onto the need to fight – and to live. Inspired by a real clinic, Rabe finds humor and compassion in a raft of richly drawn characters adrift in a society and a system stretched beyond capacity. -

Hamlet West End Announcement

FOLLOWING A CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED & SELL-OUT RUN AT THE ALMEIDA THEATRE HAMLET STARRING THE BAFTA & OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING ANDREW SCOTT AND DIRECTED BY THE MULTI AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR ROBERT ICKE WILL TRANSFER TO THE HAROLD PINTER THEATRE FOR A STRICTLY LIMITED SEASON FROM 9 JUNE – 2 SEPTEMBER 2017 ‘ANDREW SCOTT DELIVERS A CAREER-DEFINING PERFORMANCE… HE MAKES THE MOST FAMOUS SPEECHES FEEL FRESH AND UNPREDICTABLE’ EVENING STANDARD ‘IT IS LIVEWIRE, EDGE-OF-THE-SEAT STUFF’ TIME OUT Olivier Award-winning director, Robert Icke’s (Mary Stuart, The Red Barn, Uncle Vanya, Oresteia, Mr Burns and 1984), ground-breaking and electrifying production of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, starring BAFTA award-winner Andrew Scott (Moriarty in BBC’s Sherlock, Denial, Spectre, Design For Living and Cock) in the title role, will transfer to the Harold Pinter Theatre, following a critically acclaimed and sell out run at the Almeida Theatre. Hamlet will run for a limited season only from 9 June to 2 September 2017 with press night on Thursday 15 June. Hamlet is produced by Ambassador Theatre Group (Sunday In The Park With George, Buried Child, Oresteia), Sonia Friedman Productions and the Almeida Theatre (Chimerica, Ghosts, King Charles III, 1984, Oresteia), who are renowned for introducing groundbreaking, critically acclaimed transfers to the West End. Rupert Goold, Artistic Director, Almeida Theatre said "We’re delighted that with this transfer more people will be able to experience our production of Hamlet. Robert, Andrew, and the entire Hamlet company have created an unforgettable Shakespeare which we’re looking forward to sharing even more widely over the summer in partnership with Sonia Friedman Productions and ATG.” Robert Icke, Director (and Almeida Theatre Associate Director) said “It has been such a thrill to work with Andrew and the extraordinary company of Hamlet on this play so far, and I'm delighted we're going to continue our work on this play in the West End this summer. -

Willy Russell

OUR SPONSORS ABOUT CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY UP NEXT FROM CENTER REP Chevron (Season Sponsor) has been the Center REP is the resident, professional “Freaky Friday captures the best of great Disney leading corporate sponsor of Center REP theatre company of the Lesher Center for the musicals. The catchy, surprisingly deep score by CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY and the Lesher Center for the Arts for the Arts. Our season consists of six productions Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey is their best work since Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director past eleven years. In fact, Chevron has been a year – a variety of musicals, dramas and Next to Normal.” a partner of the LCA since the beginning, comedies, both classic and contemporary, – Buzzfeed providing funding for capital improvements, that continually strive to reach new levels of event sponsorships and more. Chevron artistic excellence and professional standards. generously supports every Center REP show throughout the season, and is the primary Our mission is to celebrate the power sponsor for events including the Chevron of the human imagination by producing Family Theatre Festival in July. Chevron emotionally engaging, intellectually involving, has proven itself not just as a generous and visually astonishing live theatre, and supporter, but also a valued friend of the arts. through Outreach and Education programs, to enrich and advance the cultural life of the Diablo Regional Arts Association (DRAA) communities we serve. (Season Partner) is both the primary fundraising organization of the Lesher What does it mean to be a producing Center for the Arts (LCA) and the City of theatre? We hire the finest professional BOOK BY MUSIC BY LYRICS BY Walnut Creek’s appointed curator for the directors, actors and designers to create our BRIDGET CARPENTER TOM KITT BRIAN YORKEY LCA’s audience outreach. -

Rewriting Theatre History in the Light of Dramatic Translations

Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis literaris. Vol. XV (2010) 195-218 TEXT, LIES, AND LINGUISTIC RAPE: REWRITING THEATRE HISTORY IN THE LIGHT OF DRAMATIC TRANSLATIONS John London Goldsmiths, University of London Grup de Recerca en Arts Escèniques, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Although the translation of dramatic texts has received considerable scholarly attention in the last twenty years, a great deal of this energy has been devoted to theoretical or practical issues concerned with staging. The specific linguistic features of performed translations and their subsequent reception in the theatrical culture of their host nations have not been studied so prominently. Symptomatic of this is the sparse treatment given to linguistic translation in general analyses of theatrical reception (Bennett, 1997: 191- 196). Part of the reluctance to examine the fate of transformed verbal language in the theatre can be attributed to the kinds of non-text-based performance which evolved in the 1960s and theoretical discourses which, especially in France, sought to dislodge the assumed dominance of the playtext. According to this reasoning, critics thus paid “less attention to the playwrights’ words or creations of ‘character’ and more to the concept of ‘total theatre’ ” (Bradby & Delgado, 2002: 8). It is, above all, theatre history that has remained largely untouched by detailed linguistic analysis of plays imported from another country and originally written in a different language. While there are, for example, studies of modern European drama in Britain (Anderman, 2005), a play by Shakespeare in different French translations (Heylen, 1993) or non-Spanish drama in Spain (London, 1997), these analyses never really become part of mainstream histories of British, French or Spanish theatre. -

Oliver-Programme.Pdf

7 – 17 December at 7.30pm (no Sunday performance) Matinees 10 & 17 December at 2.30pm OLIVER!by Lionel Bart Free when mailed to £1 Loft Members notes from the DIRECTOR A Dickens of a musical Oliver! is a stage musical with both music and lyrics by Lionel Bart, and was the first musical adaptation of a famous Charles Dickens work to become a stage hit. It premiered in the West End in 1960, enjoying a long run, and a subsequent successful run on Broadway, followed by numerous tours sparkling musical score that includes a host and revivals both here and the US. It was of well-known songs including Food, Glorious made into the famous musical film of the Food, Where is Love, Consider Yourself, Pick a same name in 1968, which featured an all- Pocket or Two and As Long As He Needs Me. star cast including Ron Moody, Oliver Reed, As a director, I relish challenges Shani Wallis and Jack Wild with Mark Lester which continue to stretch the skills and in the title role, and which went on to win imagination. This has included musicals such no less than six Academy Awards from as the Sondheim classic, Sweeney Todd, 11 nominations! Godspell and previous Christmas treats Oliver! has also been performed literally like Scrooge and RENT. Oliver! requires a thousands of times in British schools, highly skilled and committed team to bring particularly in the 1970s, when it was by the show to our stage – a stage where far the most popular school musical. Indeed you would not normally expect to see a the director himself appeared in an all-male show of this size – and putting the whole production in 1970 as a member of Fagin’s thing together has been a huge theatrical gang, following on from his performance challenge for the team. -

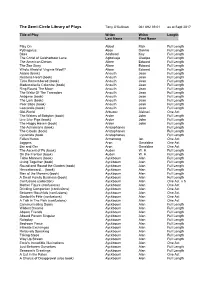

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'sullivan 061 692 39 01 As at Sept 2017

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'Sullivan 061 692 39 01 as at Sept 2017 Title of Play Writer Writer Length Last Name First Name . Play On Abbot Rick Full Length Pythagorus Abse Dannie Full Length Bites Adshead Kay Full Length The Christ of Coldharbour Lane Agboluaje Oladipo Full Length The American Dream Albee Edward Full Length The Zoo Story Albee Edward Full Length Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee Edward Full Length Ardele (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Restless Heart (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Time Remembered (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Mademoiselle Colombe (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Ring Round The Moon Anouilh Jean Full Length The Waltz Of The Toreadors Anouilh Jean Full Length Antigone (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length The Lark (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Poor Bitos (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Leocardia (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Old-World Arbuzov Aleksei One Act The Waters of Babylon (book) Arden John Full Length Live Like Pigs (book) Arden John Full Length The Happy Haven (book) Arden John Full Length The Acharnians (book) Aristophanes Full Length The Clouds (book) Aristophanes Full Length Lysistrata (book Aristophanes Full Length Fallen Heros Armstrong Ian One Act Joggers Aron Geraldine One Act Bar and Ger Aron Geraldine One Act The Ascent of F6 (book) Auden W. H. Full Length On the Frontier (book) Auden W. H. Full Length Table Manners (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Living Together (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Round and Round the Garden (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Henceforward...