Noises Off! the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asolo Rep Continues Its 60Th Season with NOISES OFF Directed By

NOISES OFF Page 1 of 7 **FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE** February 25, 2019 Asolo Rep Continues its 60th Season with NOISES OFF Directed by Comedic Broadway Veteran Don Stephenson March 20 - April 20 (SARASOTA, February 25, 2019) — Asolo Rep continues its celebration of 60 years on stage with Tony Award®-winner Michael Frayn's rip-roaringly hilarious play NOISES OFF, one of the most celebrated farces of all time. Directed by comedic Broadway veteran Don Stephenson, NOISES OFF previews March 20 and 21, opens March 22 and runs through April 20 in rotating repertory in the Mertz Theatre, located in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts. A comedy of epic proportions, NOISES OFF has been the laugh-until-you-cry guilty pleasure of audiences for decades. With opening night just hours away, a motley company of actors stumbles through a frantic, final rehearsal of the British sex farce Nothing On, and things could not be going worse. Lines are forgotten, love triangles are unraveling, sardines are flying everywhere, and complete pandemonium ensues. Will the cast pull their act together on stage even if they can't behind the scenes? “With Don Stephenson, an extraordinary comedic actor and director at the helm, this production of NOISES OFF is bound to be one of the funniest theatrical experiences we have ever presented,” said Asolo Rep Producing Artistic Director Michael Donald Edwards. “I urge the Sarasota community to take a break and escape to NOISES OFF, a joyous celebration of the magic of live theatre.” Don Stephenson's directing work includes Titanic (Lincoln Center, MUNY), Broadway Classics (Carnegie Hall),Of Mice and Manhattan (Kennedy Center), A Comedy of Tenors (Paper Mill Playhouse) and more. -

The Seagull Anton Chekhov Adapted by Simon Stephens

THE SEAGULL ANTON CHEKHOV ADAPTED BY SIMON STEPHENS major sponsor & community access partner WELCOME TO THE SEAGULL The artists and staff of Soulpepper and the Young Centre for the Performing Arts acknowledge the original caretakers and storytellers of this land – the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and Wendat First Nation, and The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation who are part of the Anishinaabe Nation. We commit to honouring and celebrating their past, present and future. “All around the world and throughout history, humans have acted out the stories that are significant to them, the stories that are central to their sense of who they are, the stories that have defined their communities, and shaped their societies. When we talk about classical theatre we want to explore what that means from the many perspectives of this city. This is a celebration of our global canon.” – Weyni Mengesha, Soulpepper’s Artistic Director photo by Emma Mcintyre Partners & Supporters James O’Sullivan & Lucie Valée Karrin Powys-Lybbe & Chris von Boetticher Sylvia Soyka Kathleen & Bill Troost 2 CAST & CREATIVE TEAM Cast Ghazal Azarbad Stuart Hughes Gregory Prest Marcia Hugo Boris Oliver Dennis Alex McCooeye Paolo Santalucia Peter Sorin Simeon Konstantin Raquel Duffy Kristen Thomson Sugith Varughese Pauline Irina Leo Hailey Gillis Dan Mousseau Nina Jacob Creative Team Daniel Brooks Matt Rideout Maricris Rivera Director Lead Audio Engineer Producing Assistant Anton Chekhov Weyni Mengesha Megan Woods Playwright Artistic Director Associate Production Manager Thomas Ryder Payne Emma Stenning Corey MacVicar Sound Designer Executive Director Associate Technical Director Frank Cox-O’Connell Tania Senewiratne Nik Murillo Associate Director Executive Producer Marketer Gregory Sinclair Mimi Warshaw Audio Producer Producer Thank You To Michelle Monteith, Daren A. -

David Rabe's Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast with F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perl

David Rabe’s Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast With F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perlman and More t2conline.com/david-rabes-good-for-otto-gets-star-studded-cast-with-f-murray-abraham-ed-harris-mark-linn-baker-amy- madigan-rhea-perlman-and-more/ Suzanna January 30, 2018 Bowling F. Murray Abraham (Barnard), Kate Buddeke (Jane), Laura Esterman (Mrs. Garland), Nancy Giles (Marci), Lily Gladstone (Denise), Ed Harris (Dr. Michaels), Charlotte Hope (Mom), Mark Linn- Baker (Timothy), Amy Madigan (Evangeline), Rileigh McDonald (Frannie), Kenny Mellman (Jerome), Maulik Pancholy (Alex), Rhea Perlman (Nora) and Michael Rabe (Jimmy), will lite up the star in the New York premiere of David Rabe’s Good for Otto. Rhea Perlman took over the role of Nora, after Rosie O’Donnell, became ill. Directed by Scott Elliott, this production will play a limited Off-Broadway engagement February 20 – April 1, with Opening Night on Thursday, March 8 at The Pershing Square Signature Center (The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, 480 West 42nd Street). Through the microcosm of a rural Connecticut mental health center, Tony Award-winning playwright David Rabe conjures a whole American community on the edge. Like their patients and their families, Dr. Michaels (Ed Harris), his colleague Evangeline (Amy Madigan) and the clinic itself teeter between breakdown and survival, wielding dedication and humanity against the cunning, inventive adversary of mental illness, to hold onto the need to fight – and to live. Inspired by a real clinic, Rabe finds humor and compassion in a raft of richly drawn characters adrift in a society and a system stretched beyond capacity. -

Willy Russell

OUR SPONSORS ABOUT CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY UP NEXT FROM CENTER REP Chevron (Season Sponsor) has been the Center REP is the resident, professional “Freaky Friday captures the best of great Disney leading corporate sponsor of Center REP theatre company of the Lesher Center for the musicals. The catchy, surprisingly deep score by CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY and the Lesher Center for the Arts for the Arts. Our season consists of six productions Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey is their best work since Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director past eleven years. In fact, Chevron has been a year – a variety of musicals, dramas and Next to Normal.” a partner of the LCA since the beginning, comedies, both classic and contemporary, – Buzzfeed providing funding for capital improvements, that continually strive to reach new levels of event sponsorships and more. Chevron artistic excellence and professional standards. generously supports every Center REP show throughout the season, and is the primary Our mission is to celebrate the power sponsor for events including the Chevron of the human imagination by producing Family Theatre Festival in July. Chevron emotionally engaging, intellectually involving, has proven itself not just as a generous and visually astonishing live theatre, and supporter, but also a valued friend of the arts. through Outreach and Education programs, to enrich and advance the cultural life of the Diablo Regional Arts Association (DRAA) communities we serve. (Season Partner) is both the primary fundraising organization of the Lesher What does it mean to be a producing Center for the Arts (LCA) and the City of theatre? We hire the finest professional BOOK BY MUSIC BY LYRICS BY Walnut Creek’s appointed curator for the directors, actors and designers to create our BRIDGET CARPENTER TOM KITT BRIAN YORKEY LCA’s audience outreach. -

Rewriting Theatre History in the Light of Dramatic Translations

Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis literaris. Vol. XV (2010) 195-218 TEXT, LIES, AND LINGUISTIC RAPE: REWRITING THEATRE HISTORY IN THE LIGHT OF DRAMATIC TRANSLATIONS John London Goldsmiths, University of London Grup de Recerca en Arts Escèniques, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Although the translation of dramatic texts has received considerable scholarly attention in the last twenty years, a great deal of this energy has been devoted to theoretical or practical issues concerned with staging. The specific linguistic features of performed translations and their subsequent reception in the theatrical culture of their host nations have not been studied so prominently. Symptomatic of this is the sparse treatment given to linguistic translation in general analyses of theatrical reception (Bennett, 1997: 191- 196). Part of the reluctance to examine the fate of transformed verbal language in the theatre can be attributed to the kinds of non-text-based performance which evolved in the 1960s and theoretical discourses which, especially in France, sought to dislodge the assumed dominance of the playtext. According to this reasoning, critics thus paid “less attention to the playwrights’ words or creations of ‘character’ and more to the concept of ‘total theatre’ ” (Bradby & Delgado, 2002: 8). It is, above all, theatre history that has remained largely untouched by detailed linguistic analysis of plays imported from another country and originally written in a different language. While there are, for example, studies of modern European drama in Britain (Anderman, 2005), a play by Shakespeare in different French translations (Heylen, 1993) or non-Spanish drama in Spain (London, 1997), these analyses never really become part of mainstream histories of British, French or Spanish theatre. -

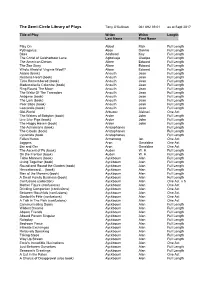

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'sullivan 061 692 39 01 As at Sept 2017

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'Sullivan 061 692 39 01 as at Sept 2017 Title of Play Writer Writer Length Last Name First Name . Play On Abbot Rick Full Length Pythagorus Abse Dannie Full Length Bites Adshead Kay Full Length The Christ of Coldharbour Lane Agboluaje Oladipo Full Length The American Dream Albee Edward Full Length The Zoo Story Albee Edward Full Length Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee Edward Full Length Ardele (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Restless Heart (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Time Remembered (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Mademoiselle Colombe (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Ring Round The Moon Anouilh Jean Full Length The Waltz Of The Toreadors Anouilh Jean Full Length Antigone (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length The Lark (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Poor Bitos (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Leocardia (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Old-World Arbuzov Aleksei One Act The Waters of Babylon (book) Arden John Full Length Live Like Pigs (book) Arden John Full Length The Happy Haven (book) Arden John Full Length The Acharnians (book) Aristophanes Full Length The Clouds (book) Aristophanes Full Length Lysistrata (book Aristophanes Full Length Fallen Heros Armstrong Ian One Act Joggers Aron Geraldine One Act Bar and Ger Aron Geraldine One Act The Ascent of F6 (book) Auden W. H. Full Length On the Frontier (book) Auden W. H. Full Length Table Manners (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Living Together (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Round and Round the Garden (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Henceforward... -

Noises Off | Full Playbill

PLAYBILL 2021 SEASON COMMUNITY CIRCLE THEATRE, INC. | FUN HOME | JULY 12-28 1 GENERAL INFORMATION BOX OFFICE HOURS MONDAY - FRIDAY | 12PM - 5PM MONDAY - FRIDAY PERFORMANCE DAYS | 12PM - CURTAIN SATURDAY | 2PM - CURTAIN SUNDAY | 12PM - CURTAIN LATE ARRIVALS Patrons arriving late will be seated at the House Manager’s discretion. NO STANDING No standing is permitted in the back of the theatre. If you become uncomfortable and/or have to move out of your seat for any reason, you may stretch your legs in the upper or lower lobby. ELECTRONIC DEVICES Please turn off all electronic devices that light up or make noise. Please, no texting. The taking of pictures and/or recordings (audio or video) is prohibited; the device may be taken from you and held until after the show. EMERGENCY CALLS If you anticipate the need to be reached in the event of an emergency, you may leave your name and seat number with the House Manager. A House Manager will also be available in the House during the run of the show. Our emergency contact number is 616 632 2996. In the event that someone is not available at this number, Aquinas College Campus Safety’s number is 616 632 2462; a dispatcher is available 24/7. YOUNG AUDIENCE Most Main Stage productions are geared toward mature audiences and may not be appropriate for younger audiences. Our Magic Circle productions provide wonderful family entertainment and an introduction to the live theatre experience. Please call the box office at 616 456 6656 for information on age appropriateness of any of our shows. -

The Circle.’ Back Row, Left to Right, Travis Vaden, Dou- Glas Weston, Nancy Bell, John Hines, Rebecca Dines and John-David Keller

38th Season • 365th Production MAINSTAGE / AUGUST 31 THROUGH OCTOBER 7, 2001 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents by W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design RALPH FUNICELLO WALKER HICKLIN YORK KENNEDY Composer/Sound Design Production Manager Stage Manager MICHAEL ROTH TOM ABERGER *SCOTT HARRISON Directed by WARNER SHOOK AMERICAN AIRLINES, Honorary Producers PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Elizabeth Champion-Cheney ............................................................................ *Nancy Bell Arnold Champion-Cheney, M.P. ....................................................................... *John Hines Footman ................................................................................................. *John-David Keller Mrs. Anna Shenstone .................................................................................. *Rebecca Dines Teddie Luton ............................................................................................. *Douglas Weston Clive Champion-Cheney ...................................................................... *Paxton Whitehead Lady Catherine Champion-Cheney ........................................................... *Carole Shelley Lord Porteous .................................................................................. *William Biff McGuire Jr. Footman ..................................................................................................... -

Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, Written by Christopher M

BIOGRAPHY CAST IN IRONY: CAVEATS, STYLIZATION, AND INDETERMINACY IN THE BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY PLAYS OF TOM STOPPARD AND MICHAEL FRAYN by CHRISTOPHER M. SHONKA B.A. Creighton University, 1997 M.F.A. Temple University, 2000 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre 2010 This thesis entitled: Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, written by Christopher M. Shonka, has been approved for the Department of Theatre Dr. Merrill Lessley Dr. James Symons Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shonka, Christopher M. (Ph.D. Theatre) Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn Thesis directed by Professor Merrill J. Lessley; Professor James Symons, second reader Abstract This study examines Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn‘s incorporation of epistemological themes related to the limits of historical knowledge within their recent biography-based plays. The primary works that are analyzed are Stoppard‘s The Invention of Love (1997) and The Coast of Utopia trilogy (2002), and Frayn‘s Copenhagen (1998), Democracy (2003), and Afterlife (2008). In these plays, caveats, or warnings, that illustrate sources of historical indeterminacy are combined with theatrical stylizations that overtly suggest the authors‘ processes of interpretation and revisionism through an ironic distancing. -

Cast & Crew August 2005

Issue No.85 Single Copy $2.50 August, 2005 CAST & CREW “The Source For Theater Happenings” ANOTHER GREAT SUMMER AT MONMOUTH WITH THE BARD (AND OTHERS) By Muriel Kenderdine The Theater at Monmouth, designated The Shakespearean Theater of Maine by the State Legislature some years ago, is halfway through its summer season, but because it’s a repertory company, you can still see all the shows between now and August 27, and then for more fun, hang around for the fall production of A FUNNY THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO THE FORUM! This year Shakespeare is represented by THE TAMING OF THE SHREW, directed by Producing Director David Greenham, and starring Artistic Director Sally Wood as the non- conformable Kate and Tim Davis-Reed as the “ shrew tamer” Petruchio, who has “come to wive it wealthily in Padua”; and, for the first time, LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST, directed by Bill Van Horn, with some interesting gender switches! Other plays in the repertory are Frank Galati’s Tony Award-winning adaptation of John Steinbeck’s THE GRAPES OF WRATH, directed by Jeri Pitcher, with Janis Stevens as Ma Joad and Richard Price as young Tom Joad; and David Hirson’s LA BETE, directed by Lucy Smith Conroy, with Dustin Tucker as the (seemingly) obnoxious Valere with the “mile-long” (and, in Dustin’s hands, hilarious) monologues. However, says Producing Director David Greenham, “I’m really passionate about a good strong company of creative artists being together and doing great work – so it’s more about the group than about the plays for me, because I think you need a great group to do great theater!” So, again for this Equity company, now in its 36th season, Dave, along with Artistic Director Sally Wood, has gathered in the usual number of AEA artists; other seasoned professionals both from away and local, for acting, design, and technical support; and talented newcomers continuing to add to their experience. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Renée Littleton/Lauren Mcmillen [email protected], 202-600-4055 September 11, 2020 ARENA STAG

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Renée Littleton/Lauren McMillen [email protected], 202-600-4055 September 11, 2020 ARENA STAGE OPENS FALL/WINTER SEASON WITH RELEASE OF THIRD WORLD-PREMIERE FILM, THE 51ST STATE *** Arena’s latest film centers around the historic fight for D.C. statehood, the protests after the murder of George Floyd and the growing movement for racial justice *** (Washington, D.C.) Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater’s latest world premiere docudrama, The 51st State, will receive its world premiere through Arena Stage’s Supper Club on September 16 at 7 p.m. Following the premiere, viewers can join artists and creatives for a post-film discussion and after-party on Zoom. The film will be available online to the general public on Thursday, September 17. Patrons will be able to view the film on both the Arena Stage and WTOP.com websites by searching for Arena Stage. The hyper local 60-minute film created by Washington, D.C. artists through the voices of 11 residents was inspired by protests and the reignition of a movement after the murder of George Floyd and the quest for creating the 51st state and sovereignty in Washington, D.C. From a first-time protestor to a fourth-generation Washingtonian political scientist, to artists, an attorney, people of faith, and a retired couple moved to take part in the movement despite the COVID-19 risks, these diverse perspectives and real-life stories are vividly told and transformed into affecting narratives by 10 local playwrights. “This is a hyper-local docudrama about a city in transition. -

LOCANTRO Theatre

Tony Locantro Programmes – Theatre MSS 792 T3743.L Theatre Date Performance Details Albery Theatre 1997 Pygmalion Bernard Shaw Dir: Ray Cooney Roy Marsden, Carli Norris, Michael Elphick 2004 Endgame Samuel Beckett Dir: Matthew Warchus Michael Gambon, Lee Evans, Liz Smith, Geoffrey Hutchins Suddenly Last Summer Tennessee Williams Dir: Michael Grandage Diana Rigg, Victoria Hamilton 2006 Blackbird Dir: Peter Stein Roger Allam, Jodhi May Theatre Date Performance Details Aldwych Theatre 1966 Belcher’s Luck by David Mercer Dir: David Jones Helen Fraser, Sebastian Shaw, John Hurt Royal Shakespeare Company 1964 (The) Birds by Aristophanes Dir: Karolos Koun Greek Art Theatre Company 1983 Charley’s Aunt by Brandon Thomas Dir: Peter James & Peter Wilson Griff Rhys Jones, Maxine Audley, Bernard Bresslaw 1961(?) Comedy of Errors by W. Shakespeare Christmas Season R.S.C. Diana Rigg 1966 Compagna dei Giovani World Theatre Season Rules of the Game & Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello Dir: Giorgio de Lullo (in Italian) 1964-67 Royal Shakespeare Company World Theatre Season Brochures 1964-69 Royal Shakespeare Company Repertoire Brochures 1964 Royal Shakespeare Theatre Club Repertoire Brochure Theatre Date Performance Details Ambassadors 1960 (The) Mousetrap Agatha Christie Dir: Peter Saunders Anthony Oliver, David Aylmer 1983 Theatre of Comedy Company Repertoire Brochure (including the Shaftesbury Theatre) Theatre Date Performance Details Alexandra – Undated (The) Platinum Cat Birmingham Roger Longrigg Dir: Beverley Cross Kenneth