The Film Producer As a Creative Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Sir Alan Parker Donates Working Archives to Bfi

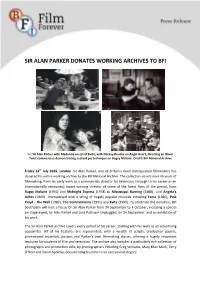

SIR ALAN PARKER DONATES WORKING ARCHIVES TO BFI l-r: Sir Alan Parker with Madonna on set of Evita; with Mickey Rourke on Angel Heart; directing an Oliver Twist commercial; demonstrating custard pie technique on Bugsy Malone. Credit: BFI National Archive Friday 24th July 2015, London. Sir Alan Parker, one of Britain’s most distinguished filmmakers has donated his entire working archive to the BFI National Archive. The collection covers over 45 years of filmmaking, from his early work as a commercials director for television, through to his career as an internationally renowned, award-winning director of some of the finest films of the period, from Bugsy Malone (1976) and Midnight Express (1978) to Mississippi Burning (1988) and Angela’s Ashes (1999) interspersed with a string of hugely popular musicals including Fame (1980), Pink Floyd - The Wall (1982), The Commitments (1991) and Evita (1996). To celebrate the donation, BFI Southbank will host a Focus On Sir Alan Parker from 24 September to 4 October, including a special on stage event, Sir Alan Parker and Lord Puttnam Unplugged, on 24 September, and an exhibition of his work. The Sir Alan Parker archive covers every period of his career, starting with his work as an advertising copywriter. All of his features are represented, with a wealth of scripts, production papers, promotional materials, posters and Parker’s own filmmaking diaries, offering a hugely important resource for students of film and television. The archive also includes a particularly rich collection of photographs and production stills, by photographers including Greg Williams, Mary Ellen Mark, Terry O'Neill and David Appleby, documenting his films to an exceptional degree. -

Café Society

Presents CAFÉ SOCIETY A film by Woody Allen (96 min., USA, 2016) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia CAFÉ SOCIETY Starring (in alphabetical order) Rose JEANNIE BERLIN Phil STEVE CARELL Bobby JESSE EISENBERG Veronica BLAKE LIVELY Rad PARKER POSEY Vonnie KRISTEN STEWART Ben COREY STOLL Marty KEN STOTT Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Candy ANNA CAMP Leonard STEPHEN KUNKEN Evelyn SARI LENNICK Steve PAUL SCHNEIDER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producer HELEN ROBIN Executive Producers ADAM B. STERN MARC I. STERN Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Cinematographer VITTORIO STORARO AIC, ASC Production Designer SANTO LOQUASTO Editor ALISA LEPSELTER ACE Costume Design SUZY BENZINGER Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DiCERTO 2 CAFÉ SOCIETY Synopsis Set in the 1930s, Woody Allen’s bittersweet romance CAFÉ SOCIETY follows Bronx-born Bobby Dorfman (Jesse Eisenberg) to Hollywood, where he falls in love, and back to New York, where he is swept up in the vibrant world of high society nightclub life. Centering on events in the lives of Bobby’s colorful Bronx family, the film is a glittering valentine to the movie stars, socialites, playboys, debutantes, politicians, and gangsters who epitomized the excitement and glamour of the age. Bobby’s family features his relentlessly bickering parents Rose (Jeannie Berlin) and Marty (Ken Stott), his casually amoral gangster brother Ben (Corey Stoll); his good-hearted teacher sister Evelyn (Sari Lennick), and her egghead husband Leonard (Stephen Kunken). -

Public Politics/Personal Authenticity

PUBLIC POLITICS/PERSONAL AUTHENTICITY: A TALE OF TWO SIXTIES IN HOLLYWOOD CINEMA, 1986- 1994 Oliver Gruner Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies August, 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One “The Enemy was in US”: Platoon and Sixties Commemoration 62 Platoon in Production, 1976-1982 65 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Platoon from Script to Screen 73 From Vietnam to the Sixties: Promotion and Reception 88 Conclusion 101 Chapter Two “There are a lot of things about me that aren’t what you thought”: Dirty Dancing and Women’s Liberation 103 Dirty Dancing in Production, 1980-1987 106 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Dirty Dancing from Script to Screen 114 “Have the Time of Your Life”: Promotion and Reception 131 Conclusion 144 Chapter Three Bad Sixties/ Good Sixties: JFK and the Sixties Generation 146 Lost Innocence/Lost Ignorance: Kennedy Commemoration and the Sixties 149 Innocence Lost: Adaptation and Script Development, 1988-1991 155 In Search of Authenticity: JFK ’s “Good Sixties” 164 Through the Looking Glass: Promotion and Reception 173 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four “Out of the Prison of Your Mind”: Framing Malcolm X 188 A Civil Rights Sixties 191 A Change -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Open PDF 120KB

Written evidence submitted by Professor Robert Beveridge FRSA The Digital Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee Inquiry into the Impact of Covid-19 on the DCMS Sector 1 What has been the immediate impact of Covid-19 on the sector? Devastating: especially in relation to the live creative arts, festivals, theatres, classical music etc. To quote the motto of the English monarch Edward III, ‘it is as it is’ but the sight of theatres going into administration eg the Leicester Haymarket and the Southampton Nuffield is a harbinger of worse to come. Who knows what will happen to venues and concert halls such as the Usher Hall in Edinburgh? If there is one area in which the UK can truly be said to have punched above it’s weight and established and maintained world class excellence, both critically and commercially, it is in the creative industries. This internationally recognised success –economic, cultural and artistic is now at severe risk. HMG has invested, (who knows how much?) in maintaining employment in the car industry in the North East of England so that Nissan can stay there. The creative industries deserve no less, indeed much more and investment now will secure many more jobs across the UK with wider benefits well beyond the economic. Taking the long view will produce future income in taxation from the many other businesses which benefit from having such a vibrant sector: hotels, restaurants, transport etc. Edinburgh hosts the largest are festival in the world, by some margin and it will not take place in 2020. The analysis provided by the Creative Industries Federation indicates the scale of current crisis. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

Feature Films

MARCELO ZARVOS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS CINEMA BRAZIL GRAND PRIZE FLORES RARAS NOMINATION (2014) Best Original Music ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION PHIL SPECTOR ASSOCIATION AWARD NOMINATION (2013) Best Music in a Non-Series BLACK REEL AWARDS BROOKLYN’S FINEST NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score EMMY AWARD NOMINATION YOU DON’T KNOW JACK (2010) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION TAKING CHANCE (2009) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) BRAZILIA FESTIVAL OF UMA HISTÓRIA DE FUTEBOL BRAZILIAN CINEMA AWARD (1998) 35mm Shorts- Best Music FEATURE FILMS MAPPLETHORPE Eliza Dushku, Nate Dushku, Ondi Timoner, Richard J. Interloper Films Bosner, prods. Ondi Timoner, dir. THE CHAPERONE Kelly Carmichael, Rose Ganguzza, Elizabeth McGovern, Anonymous Content Gary Hamilton, prods. Michael Engler, dir. BEST OF ENEMIES Tobey Maguire, Matt Berenson, Matthew Plouffe, Danny Netflix / Likely Story Strong, prods. Robin Bissell, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 MARCELO ZARVOS LAND OF STEADY HABITS Nicole Holofcener, Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu, Netflix / Likely Story prods. Nicole Holofcener, dir. WONDER David Hoberman, Todd Lieberman, prods. Lionsgate Stephen Chbosky, dir. FENCES Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington, prods. Paramount Pictures Denzel Washington, dir. ROCK THE KASBAH Steve Bing, Bill Block, Mitch Glazer, Jacob Pechenik, Open Road Films Ethan Smith, prods. Barry Levinson, dir. OUR KIND OF TRAITOR Simon Cornwell, Stephen Cornwell, Gail Egan, prods. The Ink Factory Susanna White, dir. AMERICAN ULTRA David Alpert, Anthony Bregman, Kevin Scott Frakes, Lionsgate Britton Rizzio, prods. Nima Nourizadeh, dir. THE CHOICE Theresa Park, Peter Safran, Nicholas Sparks, prods. Lionsgate Ross Katz, dir. CELL Michael Benaroya, Shara Kay, Richard Saperstein, Brian Benaroya Pictures Witten, prods. -

500M 57 29 11 9 39

29 2008 Warner Bros. 27 series for 10 networks 57 39 20th Century Fox TV 20 broadcast Universal Television 2013 7 basic cable 43 original series for 16 networks* 22 for broadcast 18 basic cable 11 19 ABC Studios 2 pay cable 1 digital Growth Sony Pictures *16 new series in 2013-14 Television Fox TV Studios 2013 Emmy 9 Nominations CBS Television Studios 20th Century Fox Television Fox 21 Studios Cable series: 2013-14 20 20th Century Fox TV 15 Warner Bros. Output ABC “Modern Family” 10 Universal Television CBS “How I Met Your Mother” 7 Sony Pictures Television USA “Burn Notice” USA “White Collar” 2 ABC Studios SHO “Homeland” 2 CBS Television Studios Third-Party Broadcast series: 2013-14 Network Hits 34 Warner Bros. 22 20th Century Fox TV 18 ABC Studios 18 Universal Television 17 CBS Television Studios 11 Sony Pictures Television “American Dad” “Bob’s Burgers” “Family Guy” “Futurama” The World of “How I Met Your Mother” “King of the Hill” Off-Network “Last Man Standing” Brian Grazer & Ron Howard Dana Walden & Pipeline (2015-16) (“24,” “Arrested Development”) “Modern Family” “New Girl” (2015-16) Gary Newman “Raising Hope” Howard Gordon (2014-15) (“The X-Files,” “24,” “The Simpsons” “Homeland,” Diverse in both content and “Legends,” “Tyrant”) outlets, 20th Century Fox TV has flourished under the leadership of its chairman-CEOs. Key Exec “Angel” Producers Key Library “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” Series “King of the Hill” “MASH” “Prison Break” “Reba” “24” Seth MacFarlane “The X-Files” (“Family Guy,” More than 50 current “American Dad,” “The and -

(XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: the UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 Min

November 8, 2016 (XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: THE UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot url links.) DIRECTED BY Brian De Palma WRITING CREDITS David Mamet (written by), Oscar Fraley & Eliot Ness (suggested by book) PRODUCED BY Art Linson MUSIC Ennio Morricone CINEMATOGRAPHY Stephen H. Burum FILM EDITING Gerald B. Greenberg and Bill Pankow Kevin Costner…Eliot Ness Sean Connery…Jimmy Malone Charles Martin Smith…Oscar Wallace Andy García…George Stone/Giuseppe Petri Robert De Niro…Al Capone Patricia Clarkson…Catherine Ness Billy Drago…Frank Nitti Richard Bradford…Chief Mike Dorsett earning Oscar nominations for the two lead females, Piper Jack Kehoe…Walter Payne Laurie and Sissy Spacek. His next major success was the Brad Sullivan…George controversial, ultra-violent film Scarface (1983). Written Clifton James…District Attorney by Oliver Stone and starring Al Pacino, the film concerned Cuban immigrant Tony Montana's rise to power in the BRIAN DE PALMA (b. September 11, 1940 in Newark, United States through the drug trade. The film, while New Jersey) initially planned to follow in his father’s being a critical failure, was a major success commercially. footsteps and study medicine. While working on his Tonight’s film is arguably the apex of De Palma’s career, studies he also made several short films. At first, his films both a critical and commercial success, and earning Sean comprised of such black-and-white films as Bridge That Connery an Oscar win for Best Supporting Actor (the only Gap (1965). He then discovered a young actor whose one of his long career), as well as nominations to fame would influence Hollywood forever.