Open PDF 120KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Alan Parker Donates Working Archives to Bfi

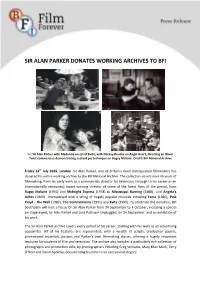

SIR ALAN PARKER DONATES WORKING ARCHIVES TO BFI l-r: Sir Alan Parker with Madonna on set of Evita; with Mickey Rourke on Angel Heart; directing an Oliver Twist commercial; demonstrating custard pie technique on Bugsy Malone. Credit: BFI National Archive Friday 24th July 2015, London. Sir Alan Parker, one of Britain’s most distinguished filmmakers has donated his entire working archive to the BFI National Archive. The collection covers over 45 years of filmmaking, from his early work as a commercials director for television, through to his career as an internationally renowned, award-winning director of some of the finest films of the period, from Bugsy Malone (1976) and Midnight Express (1978) to Mississippi Burning (1988) and Angela’s Ashes (1999) interspersed with a string of hugely popular musicals including Fame (1980), Pink Floyd - The Wall (1982), The Commitments (1991) and Evita (1996). To celebrate the donation, BFI Southbank will host a Focus On Sir Alan Parker from 24 September to 4 October, including a special on stage event, Sir Alan Parker and Lord Puttnam Unplugged, on 24 September, and an exhibition of his work. The Sir Alan Parker archive covers every period of his career, starting with his work as an advertising copywriter. All of his features are represented, with a wealth of scripts, production papers, promotional materials, posters and Parker’s own filmmaking diaries, offering a hugely important resource for students of film and television. The archive also includes a particularly rich collection of photographs and production stills, by photographers including Greg Williams, Mary Ellen Mark, Terry O'Neill and David Appleby, documenting his films to an exceptional degree. -

Not Showing at This Cinema

greenlit just before he died, was an adaptation of A PIN TO SEE THE NIGHT Walter Hamilton’s 1968 novel All the Little Animals, exploring the friendship between a boy and an THE PEEPSHOW CREATURES old man who patrols roads at night collecting the Dir: Robert Hamer 1949 Dir: Val Guest 1957 roadkill. Reeves prepared a treatment, locations Adaptation of a 1934 novel by F. Tennyson Jesse Robert Neville is the last man on earth after a were scouted and Arthur Lowe was to play the about a young woman wrongly convicted as an mysterious plague has turned the rest of the lead. Thirty years later the book was adapted for accomplice when her lover murders her husband; a population into vampires who swarm around his the screen and directed by Jeremy Thomas starring thinly fictionalised account of Edith Thompson and house every night, hungering for his blood. By day, John Hurt and Christian Bale. the Ilford Murder case of 1922. With Margaret he hunts out the vampires’ lairs and kills them Lockwood in the lead, this was something of a with stakes through the heart, while obsessively dream project that Robert Hamer tried to get off searching for an antidote and trying to work out the ground at Ealing. Despite a dazzling CV that the cause of his immunity. Richard Matheson wrote ISHTAR includes the masterpiece Kind Hearts and Coronets the screenplay for The Night Creatures for Hammer Dir: Donald Cammell 1971-73 (1949), Hamer was unable to persuade studio Films in 1957 based on his own hugely influential The co-director of Performance (1970), Cammell boss Michael Balcon to back the project. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION This study guide attempts to trace the production process o1 the forthcoming film War of the Buttons' from its Conception to its release in the cinema. In tracing this route students are asked to carry out a number of tasks, many of which relate directly to decisions which have to be made during film production. Following the development of this one film we have tried to draw conclusions about the mainstream film making process. However, it is important to bear one thing in mind. As the production accountant for 'War of the Buttons', John Trehy points out: "Each and every feature film I've worked on is completely different from every other, and can only be looked on a as prototype. The production process is always difficult when you're dealing with prototypes and this often explains why so many films exceed their original budgets. 'How can you be a million or two dollars over?' - is a question that is often asked. The reason is that certain kinds of films are unique and the production team must do things that have never been done before." Thus, whilst many of the processes which are dealt with in this guide could well hold good for other films, there are certain aspects which are unique. The guide examines both areas and encourages students to use their own experience of film viewing and cinema-going to explore both the generalities and the uniqueness. There is no attempt to show 'the wonderful world of filmmaking'; rather the guide reveals an industrial process, one in which the time spent on preparing for the film to be shot far outweighs the amount of time actually spent shooting. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

JOHN PARDUE BSC - Director of Photography (UK and USA PASSPORT HOLDER)

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JOHN PARDUE BSC - Director of Photography (UK and USA PASSPORT HOLDER) FOUR KIDS & IT Director: Andy De Emmony. Producer: Julie Baines, Anne Brogan, Jonathan Taylor. Starring: Michael Caine, Bill Nighy. Dan Films / Kindle Entertainment. LUTHER 5 Director: Jamie Payne. Producer: Derek Ritchie. Starring: Idris Elba, Dermot Crowley and Wunmi Mosaku. BBC. THE HUSTLE (Feature Film, 2nd Unit – Mallorca) Director: Chris Addison. Producers: Roger Birnbaum and Rebel Wilson Starring: Anne Hathaway and Rebel Wilson and David Hayman. Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer FINDING YOUR FEET Director: Richard Loncraine. Producers: Nick Moorcroft, Andrew Berg, Meg Leonard and Richard Wheelan. Starring: Imelda Staunton, Celia Imrie, Timothy Spall, Joanna Lumley and David Hayman. Eclipse Films / Powder Keg Pictures / Catalyst. DIRK GENTLY’S HOLISTIC DETECTIVE AGENCY Director (Pilot episodes 1 & 2): Dean Parisot. Director (Episodes 5 & 6): Tamra Davis. Producers: Max Landis, Robert Cooper, Arvind Ethan David and Kim Todd. Starring: Elijah Wood, Samuel Barnett, Hannah Marks and Richard Schiff. Circle of Confusion / BBC America / Netflix. QUACKS (TV pilot - series commissioned) Director: Andy De Emmony. Producers: James Wood and Justin Davies. Starring: Rupert Everett, Rory Kinnear, Tom Basden, Matthew Baynton Lucky Giant. AND THEN THERE WERE NONE Director: Craig Viveiros. Producers: Abi Bach and Damien Timmer. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JOHN PARDUE Contd … 2 Starring: Charles Dance, Toby Stephens, Miranda Richardson and Sam Neill. Mammoth Screen / BBC. STAN LEE’S LUCKY MAN (Season 1, Opening Episodes 1 & 2 tone establisher) Director: Andy De Emmony. -

PERRY/REECE CASTING Penny Perry 310-422-1581-Cell Phone 818-905-9917-Home Phone

PERRY/REECE CASTING Penny Perry 310-422-1581-Cell Phone 818-905-9917-Home Phone MOTION PICTURES PORKY’S: THE COLLEGE YEARS Larry Levinson Productions Adam Wylie Producer: Larry Levinson Vic Polizos Director: Brian Trenchard-Smith THE INVITED Dark Portal, LLC. Lou Diamond Phillips Producer: Dan Kaplow Megan Ward Director: Ryan McKinney Brenda Vaccaro Pam Greer WHEN CALLS THE HEART Maggie Grace Producer & Director: Michael Landon Peter Coyote DISAPPEARANCES Border Run Productions Kris Kristofferson Producer & Director: Jay Craven Genevieve Bujold Lothaire Bluteau Luis Guzman FEAR X John Turturro Producer: Henrik Danstrup James Remar Director: Nicolas Winding Refn Deborah Unger DIAL 9 FOR LOVE Pleswin Entertainment Jeanne Tripplehorn Producer: Eric Pleskow /Leon de Winter Liev Schreiber Director: Kees Van Oostrom Louise Fletcher Co-Producer: Penny Perry THE HOLLYWOOD SIGN Pleswin Entertainment Burt Reynolds Producer: Eric Pleskow/Leon de Winter Rod Steiger Producer: Penny Perry Tom Berenger Director: Sonke Wortmann EXTREME OPS Diamant/Cohen Productions Brigette Wilson-Sampras Director: Christian Dugay Devon Sawa Rupert Graves FEAR.COM Diamant/Cohen Productions Stephen Dorff Producer: Moshe Diamant Natascha McElhone Director: William Malone Stephen Rea BIG BAD LOVE Sun, Moon & Stars Prod. Deborah Winger Producer: Barry Navidi Arliss Howard Director: Arliss Howard Rosanna Arquette Paul LeMat THE MUSKETEER Universal Mena Suvari Director: Peter Hyams Tim Roth Producer: Moshe Diamant Catherine Denueve Producer: Mark Damon Stephen Rea Nick Moran -

The Future: the Fall and Rise of the British Film Industry in the 1980S

THE FALL AND RISE OF THE BRITISH FILM INDUSTRY IN THE 1980S AN INFORMATION BRIEFING National Library Back to the Future the fall and rise of the British Film Industry in the 1980s an information briefing contents THIS PDF IS FULLY NAVIGABLE BY USING THE “BOOKMARKS” FACILITY IN ADOBE ACROBAT READER SECTION I: REPORT Introduction . .1 Britain in the 1980s . .1 Production . .1 Exhibition . .3 TV and Film . .5 Video . .7 “Video Nasties” & Regulation . .8 LEADING COMPANIES Merchant Ivory . .9 HandMade Films . .11 BFI Production Board . .12 Channel Four . .13 Goldcrest . .14 Palace Pictures . .15 Bibliography . .17 SECTION II: STATISTICS NOTES TO TABLE . .18 TABLE: UK FILM PRODUCTIONS 1980 - 1990 . .19 Written and Researched by: Phil Wickham Erinna Mettler Additional Research by: Elena Marcarini Design/Layout: Ian O’Sullivan © 2005 BFI INFORMATION SERVICES BFI NATIONAL LIBRARY 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN ISBN: 1-84457-108-4 Phil Wickham is an Information Officer in the Information Services of the BFI National Library. He writes and lectures extensively on British film and television. Erinna Mettler worked as an Information Officer in the Information Services of the BFI National Library from 1990 – 2004. Ian O’Sullivan is also an Information Officer in the Information Services of the BFI National Library and has designed a number of publications for the BFI. Elena Marcarini has worked as an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the BFI National Library. The opinions contained within this Information Briefing are those of the authors and are not expressed on behalf of the British Film Institute. Information Services BFI National Library British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Tel: + 44 (0) 20 7255 1444 Fax: + 44 (0) 20 7436 0165 Try the BFI website for film and television information 24 hours a day, 52 weeks a year… Film & TV Info – www.bfi.org.uk/filmtvinfo - contains a range of information to help find answers to your queries. -

THE BRITISH FILM INDUSTRY an Interview with David Puttnam

32 February 1982 Marxism Today Do you think the situation has deteriorated? Yes, it deteriorated a few weeks ago with the incorporation of United Artists into CIC — or whatever it's now called. It deteriorated THE BRITISH FILM INDUSTRY three years ago when EMI lined up with An interview with David Puttnam Warner-Columbia into Warner-Columbia- EMI. It's deteriorated very rapidly in the last five years. David Puttnam is one of Britain's the lottery which making a feature film is most successful independent film pro- without a world market? Is this a critique of a market system? That the ducers with a track record that in- needs of the audience, the needs of the film- cludes; That'll Be The Day, Stardust, That's hugely significant. There's no ques- maker are not met? Mahler, Bugsy Malone, The Duellists, ' tion that their grip — and they had it by Midnight Express, Foxes, Chariots of 1930, before sound — is related to the fact Yes, that's what I think. I've supported Alan Fire. Here he is interviewed by Roy that they have many, many more ways of Sapper (ACTT's General Secretary) for Lockett who is deputy general secretary hedging their bets for an equivalent invest- years in the notion that what we need in this of the ACTT. ment, than a British company has. Five mil- country is a nationalised, vertically inte- lion pounds invested by a British company grated sector not run by market forces; given Is it possible for us to say that there is an in a British film is a far, far higher risk a different brief. -

'A British Empire of Their Own? Jewish Entrepreneurs in the British Film

‘A British Empire of Their Own? Jewish Entrepreneurs in the British Film Industry’ Andrew Spicer (University of the West of England) Introduction The importance of Jewish entrepreneurs in the development of Hollywood has long been recognized, notably in Neil Gabler’s classic study, An Empire of Their Own (1988). No comparable investigation and analysis of the Jewish presence in the British film industry has been conducted.1 This article provides a preliminary overview of the most significant Jewish entrepreneurs involved in British film culture from the early pioneers through to David Puttnam. I use the term ‘entrepreneur’ rather than ‘film-maker’ because I am analyzing film as an industry, thus excluding technical personnel, including directors.2 Space restrictions have meant the reluctant omission of Sidney Bernstein and Oscar Deutsch because the latter was engaged solely in cinema building and the former more significant in the development of commercial television.3 I have also confined myself to Jews born in the UK, thus excluding the Danziger brothers, Filippo del Giudice, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, Alexander Korda, Harry Saltzman and Max Schach.4 I should emphasize that my aim is to characterize the nature of the contribution of my chosen figures to the development of British cinema, not provide detailed career profiles.5 The idea that Jews controlled the British film industry surfaced most noticeably in the late 1930s when the undercurrent of anti-Semitic prejudice in British society took public forms; Isidore Ostrer, head of the giant Gaumont-British Picture Corporation (GBPC) was referred to in the House of Commons as an ‘unnaturalised alien’ (Low 1985: 243). -

Jill Nelmes Critical Appraisal - Phd by Publication

Jill Nelmes Critical Appraisal - PhD by publication Introduction: This critical appraisal is based on an overview of my published research on the subject of the screenplay between 2007 and 2014 when my most recent monograph, The Screenplay in British Cinema (BFI, 2014) 1 was produced. The aim of my research has been twofold: to bring to academic attention the depth and breadth of screenplay writing as a written form, particularly within British Cinema, and to argue that the screenplay can be studied as a literary text. My interest in researching the screenplay arose from the realisation that the screenwriter and the screenplay have received little attention within the academy. My early research argues that the screenplay exists as a separate entity from the film, while being a vital part of the film production process, and that the screenplay is a written form to which textual analysis and the comparison of different drafts of a screenplay can be applied (see Nelmes, 2007; 2009). A case study of my own screenplay was published which discusses the complex nature of the development and rewriting process and concludes that problem solving is a key part of that process (Nelmes, 2009). As a result of this article I began to look at other screenwriters who have made a significant contribution to the film industry; my research on the screenwriter Paul Laverty and his re-writing of The Wind that Shakes the Barley was published in the Journal of British Cinema and Television (2010a). The research for this led to the discovery of the BFI Special Collections and I received a British Academy grant to study the re-writing process and the draft screenplays in the Janet Green collection (Nelmes, 2010b). -

The Creation and Destruction of the UK Film Council

Schlesinger, P. (2015) The creation and destruction of the UK Film Council. In: Oakley, K. and O’Connor, J. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to the Cultural Industries. Series: Routledge companions. Routledge: London and New York, pp. 464-476. ISBN 9780415706209. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/108211/ Deposited on: 16 September 2015 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 THE CREATION AND DESTRUCTION OF THE UK FILM COUNCIL Chapter 37 (pp.464-476) in Kate Oakley and Justin O’Connor (eds) The Routledge Companion to the Cultural Industries London and New York: Routledge, 2015 ISBN 978-0-415-70629-9 (hbk) Philip Schlesinger INTRODUCTION Established by a Labour government in April 2000 and wound up at the end of March 2011 by a Conservative-led coalition, the UK Film Council (UKFC) was the key strategic body responsible for supporting the film industry and film culture in Britain for over a decade. Cultural agencies such as the UKFC may be conjured into life by governments of one colour and unceremoniously interred by those of another. Such decisions are of considerable interest to all those who wish to understand the nature and exercise of political power in the cultural field. The UKFC’s creation owed much to the personal commitment of Chris Smith, Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport in the ‘new’ Labour government that took office in May 1997.1 Another Culture Secretary - the Conservative Jeremy Hunt - was responsible for its peremptory demise, as a member of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat cabinet installed in May 2010.2 These individuals’ actions need to be set in the wider context of the history of British film policy and also the particular conjunctures in which they took their decisions. -

An Avalanche Is Coming: Higher Education and the Revolution Ahead CONTENTS

AN AVALANCHE IS COMING HIGHER EDUCATION AND THE REVOLUTION AHEAD ESSAY Michael Barber Katelyn Donnelly Saad Rizvi Foreword by Lawrence Summers, President Emeritus, Harvard University March 2013 © IPPR 2013 Institute for Public Policy Research AN AVALANCHE IS COMING Higher education and the revolution ahead Michael Barber, Katelyn Donnelly, Saad Rizvi March 2013 ‘It’s tragic because, by my reading, should we fail to radically change our approach to education, the same cohort we’re attempting to “protect” could find that their entire future is scuttled by our timidity.’ David Puttnam Speech at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 2012 i ABOUT THE AUTHORS Sir Michael Barber is the chief education advisor at Pearson, leading Pearson’s worldwide programme of research into education policy and the impact of its products and services on learner outcomes. He chairs the Pearson Affordable Learning Fund, which aims to extend educational opportunity for the children of low-income families in the developing world. Michael also advises governments and development agencies on education strategy, effective governance and delivery. Prior to Pearson, he was head of McKinsey’s global education practice. He previously served the UK government as head of the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (2001–05) and as chief adviser to the secretary of state for education on school standards (1997–2001). Micheal is a visiting professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow and author of numerous books including Instruction to Deliver: Fighting to Improve Britain’s Public Services (2007) which was described by the Financial Times as ‘one of the best books about British government for many years’.