Japan's Economy Implications for Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand Vol

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand Vol. 32 Edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan Published in Sydney, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2015 ISBN: 978 0 646 94298 8 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Freestone, Robert, and Nicola Pullan. “From Wilkinson to Winston: Towards a Planning Degree at the University of Sydney 1919-1949.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, 157-169. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015. Robert Freestone and Nicola Pullan, UNSW Australia From Wilkinson to Winston: Towards a Planning Degree at the University of Sydney 1919-1949 This paper explores the genesis of planning education in the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Sydney, highlighting the key roles played by architects, architectural educators and other institutional actors in the process. Town planning was identified as a key curriculum element for the Bachelor of Architecture degree at the University of Sydney in 1920, when architecture broke away from the Faculty of Engineering. The new Faculty was constituted under the leadership of Leslie Wilkinson, the first Professor of Architecture, with R. Keith Harris appointed as lecturer with special responsibility for town planning. In parallel, in 1919 the University Extension Board inaugurated the Vernon Memorial Lectures on Town Planning, a more inclusive series which offered instruction on town planning to all comers. These lectures were devised and delivered by architect- planner, John Sulman. The two initiatives would eventually merge, driven by the NSW state government’s reconstruction agenda and legislative reforms which demanded qualified planners to manage a new statutory planning system. -

Claims Resolution Tribunal

CLAIMS RESOLUTION TRIBUNAL In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation Case No. CV96-4849 Certified Award to Claimant [REDACTED 1] also acting on behalf of [REDACTED 2], [REDACTED 3], [REDACTED 4], [REDACTED 5], [REDACTED 6], and the Estate of [REDACTED 7] in re Accounts of Martin Kallir, Ludwig Kallir and Camilla Kallir Claim Number: 500666/AX1 Award Amount: 3,054,057.50 Swiss Francs This Certified Award is based upon the claim of [REDACTED 1] (the “Claimant”) to the published accounts of Martin Kallir (“Account Owner Martin Kallir”), Ludwig Kallir (“Account Owner Ludwig Kallir”), and Camilla Kallir (“Account Owner Camilla Kallir”) (together the “Account Owners”) at the Zurich branch of the [REDACTED] (the “Bank”). All awards are published, but where a claimant has requested confidentiality, as in this case, the names of the claimant, any relatives of the claimant other than the account owner, and the bank have been redacted. Information Provided by the Claimant The Claimant submitted a Claim Form identifying Account Owner Martin Kallir as his paternal grandfather and Account Owners Ludwig Kallir and Camilla Kallir as his great-uncle and great- aunt. The Claimant stated that Martin Kallir was born on 2 April 1878, in Leipzig, Germany, and was married to [REDACTED 2], née [REDACTED], on 21 November 1909 in Vienna, Austria. The Claimant indicated that Martin Kallir had two sons, [REDACTED] and [REDACTED]. The Claimant stated that his grandfather, who was Jewish, was a director of a company in Vienna at the time of the “Anschluss.” The Claimant further stated that his 1 On 25 June 2003, the Estate of [REDACTED 7] submitted two claims to the accounts of Camilla Kallir and Ludwig Kallir, which are registered under the Claim Numbers 500994 and 500995, respectively. -

Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly

5193 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thursday 4 May 2000 _____ JOINT SITTING TO ELECT A SENATOR The two Houses met in the Legislative Council Chamber at 3.40 p.m. to elect a senator in the place of Senator David Brownhill, resigned. Mr CARR: Mr Clerk, I move: That the Hon. Meredith Anne Burgmann, President of the Legislative Council, act as President of the Joint Sitting of the two Houses of the Legislature for the election of a senator in the place of Senator David Brownhill, resigned, and that in the event of her absence the Hon. John Henry Murray, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, act in that capacity. Mrs CHIKAROVSKI: I second the motion. Motion agreed to. The Hon. Dr Meredith Burgmann took the chair. Mr CARR: I present proposed rules for the regulation of the proceedings at the joint sitting, which have been printed and circulated. I move: That the proposed rules, as printed and circulated, be now adopted. Mrs CHIKAROVSKI: I second the motion. Motion agreed to. The PRESIDENT: I am now prepared to receive nominations with regard to a person to fill the vacant place in the Senate caused by the resignation of Senator David Brownhill. Mr SOURIS: I propose Mr Sandy Macdonald to hold the place in the Senate rendered vacant by the resignation of Senator David Brownhill, and I announce that the candidate is willing to hold the vacant place if chosen. Senator David Brownhill was, at the time he was chosen by the people of the State, publicly recognised to be an endorsed candidate of the National Party of Australia and publicly represented himself to be an endorsed candidate of that party. -

The Mistletoes a Literature Review

THE MISTLETOES A LITERATURE REVIEW Technical Bulletin No. 1242 June 1961 U.S. DEi>ARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE THE MISTLETOES A LITERATURE REVIEW by Lake S. Gill and Frank G. Hawksworth Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Forest Service Growth Through Agricultural Progress Technical Bulletin No. 1242 June 1961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WASHINGTON, D.C For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. - Price 35 cents Preface striking advances have been made in recent years in the field of plant pathology, but most of these investigations have dealt with diseases caused by fungi, bacteria, or viruses. In contrast, progress toward an understanding of diseases caused by phanerogamic parasites has been relatively slow. Dodder (Cuscuta spp.) and broom rape {Orohanche spp.) are well-known parasites of agri- cultural crops and are serious pests in certain localities. The recent introduction of witchweed (Striga sp.) a potentially serious pest for corn-growing areas, into the United States (Gariss and Wells 1956) emphasizes the need for more knowledge of phanerogamic parasites. The mistletoes, because of their unusual growth habits, have been the object of curiosity for thousands of years. Not until the present century, however, has their role as damaging pests to forest, park, orchard, and ornamental trees become apparent. The mistletoes are most abundant in tropical areas, but they are also widely distributed in the temperate zone. The peak of destructive- ness of this family seems to be reached in western North America where several species of the highly parasitic dwarfmistletoes (Arceuthobium spp,) occur. -

Postmaster & the Merton Record 2017

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2017 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Features Records Edited by Merton in Numbers ...............................................................................4 A long road to a busy year ..............................................................60 The Warden & Fellows 2016-17 .....................................................108 Claire Spence-Parsons, Duncan Barker, The College year in photos Dr Vic James (1992) reflects on her most productive year yet Bethany Pedder and Philippa Logan. Elections, Honours & Appointments ..............................................111 From the Warden ..................................................................................6 Mertonians in… Media ........................................................................64 Six Merton alumni reflect on their careers in the media New Students 2016 ............................................................................ 113 Front cover image Flemish astrolabe in the Upper Library. JCR News .................................................................................................8 Merton Cities: Singapore ...................................................................72 Undergraduate Leavers 2017 ............................................................ 115 Photograph by Claire Spence-Parsons. With MCR News .............................................................................................10 Kenneth Tan (1986) on his -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 451 971 RC 022 632 TITLE Katu Kalpa: Report on the Inquiry into the Effectiveness of Education and Training Programs for Indigenous Australians. INSTITUTION Australia Parliament, Canberra. Senate Employment, Workplace Relations, Small Business and Education References Committee. ISBN ISBN-0-642-71045-7 PUB DATE 2000-03-00 NOTE 214p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/EET_CTTE/indiged. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Attendance; Bilingual Education; Child Health; *Cultural Differences; Culturally Relevant Education; Educational Assessment; Educational Attainment; *Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; Extended Family; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; Literacy; Postsecondary Education; Preschool Education; Racial Discrimination; Rural Education; *School Community Relationship; Self Determination; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Aboriginal Australians; *Australia ABSTRACT An inquiry into Indigenous education by an Australian Senate committee examined government reports produced in 1989-99 and conducted school site visits and public hearings. During the inquiry, it became clear that educational equity for Indigenous people had not been achieved, and Indigenous participation and achievement rates lagged behind those of the non-Indigenous population in most sectors. Much of the inquiry focused on rural and remote regions, where Indigenous people have limited access to education. Chapter 1 of this report provides an overview -

A Centenary of Achievement National Party of Australia 1920-2020

Milestone A Centenary of Achievement National Party of Australia 1920-2020 Paul Davey Milestone: A Centenary of Achievement © Paul Davey 2020 First published 2020 Published by National Party of Australia, John McEwen House, 7 National Circuit, Bar- ton, ACT 2600. Printed by Homestead Press Pty Ltd 3 Paterson Parade, Queanbeyan NSW 2620 ph 02 6299 4500 email <[email protected]> Cover design and layout by Cecile Ferguson <[email protected]> This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the author by email to <[email protected]> or to the National Party of Australia at <[email protected]> Author: Davey, Paul Title: Milestone/A Centenary of Achievement – National Party of Australia 1920-2020 Edition: 1st ed ISBN: 978-0-6486515-1-2 (pbk) Subjects: Australian Country Party 1920-1975 National Country Party of Australia 1975-1982 National Party of Australia 1982- Australia – Politics and government 20th century Australia – Politics and government – 2001- Published with the support of John McEwen House Pty Ltd, Canberra Printed on 100 per cent recycled paper ii Milestone: A Centenary of Achievement “Having put our hands to the wheel, we set the course of our voyage. … We have not entered upon this course without the most grave consideration.” (William McWilliams on the formation of the Australian Country Party, Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, 10 March 1920, p. 250) “We conceive our role as a dual one of being at all times the specialist party with a sharp fighting edge, the specialists for rural industries and rural communities. -

Australia 2002

Asia Pacific Labour Law Review Asia Pacific Labour Law Review Workers Rights for the New Century Asia Monitor Resource Centre 2003 Asia Monitor Resource Centre Ltd. AMRC is an independent non-governmental organisation that focuses on Asian and Pacific labour concerns. The Center provides information, research, publishing, training, labour networking and related services to trade unions, pro-labour groups, and other development NGOs. AMRC’s main goal is to support democratic and independent labour movements in Asia and the Pacific. In order to achieve this goal, AMRC upholds the principles of workers’ empowerment and gender consciousness, and follows a participatory framework. Publishedby Asia Monitor Resource Centre Ltd (AMRC), 444 Nathan Road, 8-B, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China SAR Tel: (852) 2332 1346 Fax: (852) 2385 5319 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.amrc.org.hk Copyright © Asia Monitor Resource Centre Ltd, 2003 ISBN 962-7145-18-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form without prior written permission. Editorial Team Stephen Frost, Omana George, and Ed Shepherd Layout Tom Fenton Cover Design Eugene Kuo Acknowledgements AMRC expresses sincere thanks to the following people and organisations for their gratefully received contributions to this book. Suchada Boonchoo (Pun) is co-ordinator for the Asian Network for the Rights of Occupational Accident Victims. We thank her for all the help in organising our conference of authors in Bangkok. Thanks to the American Center for International Labor Solidarity, Bangkok, Thailand for a financial con- tribution towards printing the book. -

Early Australian Material in the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem

1 Early Australian Material in the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem. Hovevei Zion: A2/106 (1894-6)-3 letters-(Sydney). January 16th, 1894, Lewis Barnett (Boot and Shoe Manufacturer and Importer, 702 George Street) to D. Levy (234 Clarence Street, Sydney) asking for Chovevi Zion zionist literature and enclosing 10 shillings;[ envelope from London marked Sydney and addressed to Dr S.A. Hirsch, 186 Clarendon Gardens, MaidaVale W. 189?]; Letter of July 29th, 1895 to London, Chovevi Zion Society from D. Levy (Hon. Sec. of Executive of Chovevi Zion Society, Sydney). President of Society is Leon Dolawitch, Vice-President is Lewis Barnett, and the Committee consists of David Rose and Ephraim Michael. Letter dated 8.7.1896 fromWhite & Lampert (Commercial Store, Barraba, New South Wales) to London with a donation of ten shillings for Chovevi Zion material. 6pp. Hovevei Zion: Al8/12/6 (27th Sep 1907 + 4th Oct 1907) - 2 letters where Australia is mentioned 27th Sep 1907 and 4th October-1907 from S.Goldreich to Wolffson: 8pp. A18/12/8 (27th Apr 1909 + 2nd July 1909)-2 letters. 27th April 1909 from Alicia Barkman to Wolfsohn from the Melbourne Ladies' Branch): 3pp. Jewish Territorial Organisation: A36-67 (1904-1912) - several letters (already filmed) ea. 400pp. Apply to Archive ofAustralian Judaica for index. Zionist Congress Office in Vienna: Zl/311/1 (June 8th 1900)- Samuel Goldston, NSW to Dr Theodor Herzl: 4pp. Zl/319 (21st Jan 1900)- H. Hockings (NSW) to Herzl," We Jews of the State of New South Wales (the mother State) disire to cooperate wih kindred societies in London. -

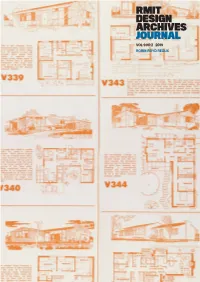

Rmit Design Archives Journal Vol 9 Nº 2 | 2019 Robin Boyd Redux Robin Boyd Redux

RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES JOURNAL | VOL 9 Nº 2 | | VOL JOURNAL RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES 9 Nº 2 RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES JOURNAL VOL 9 Nº 2 | 2019 ROBIN BOYD REDUX ROBIN BOYD REDUX BOYD ROBIN RDA_Journal_21_9.2_Cover.indd 1 27/11/19 4:58 pm Contributors Dr Karen Burns is an architectural historian and theorist in the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne. Harriet Edquist is professor in the School of Architecture and Urban Design at RMIT University and Director of RMIT Design Archives. Dr Rory Hyde is the curator of contemporary architecture and urbanism at the Victoria & Albert Museum, adjunct senior research fellow at the University of Melbourne, and design advocate for the Mayor of London. John Macarthur is professor at the University of Queensland in the School of Architecture where his research focuses on the intellectual history of architecture, the aesthetics of architecture and its relation to the visual arts. Philip Goad is Chair of Architecture and Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the University of Melbourne. He is currently Gough Whitlam Malcolm Fraser Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University for the 2019-2020 academic year. Virginia Mannering is a Melbourne-based designer, researcher and tutor in architectural design and history Dr Christine Phillips is an architect, researcher and academic within the architecture program in the School of Architecture and Urban Design at RMIT University. Dr Peter Raisbeck is an architect, researcher and academic at the Melbourne School of Design at the University of -

Electoral Management Bodies As Institutions of Governance As Institutions of Governance

UNDP Electoral Management Bodies Electoral Management Bodies as Institutions of Governance as Institutions of Governance Bureau for Development Policy United Nations Development Programme Electoral Management Bodies as Institutions of Governance Professor Rafael López-Pintor Bureau for Development Policy United Nations Development Programme 2 This paper is the fifth in a series of Discussion Papers on governance sponsored by the UNDP Bureau for Development Policy. It was com- missioned to the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES) and was researched and written by Professor Rafael López-Pintor. The views expressed in this paper are not necessarily shared by UNDP’s Executive Board or the member governments of UNDP. 3 Preface Electoral systems are the primary vehicle for choice and representa- tional governance, which is the basic foundation for democratization. These systems must provide opportunities for all, including the most disadvantaged, to participate in and influence government policy and practice. Effective management of electoral systems requires institutions that are inclusive, sustainable, just and independent– which includes in particular electoral management bodies that have the legitimacy to enforce rules and assure fairness with the cooperation of political parties and citizens. UNDP policy on governance for human development rests on the belief that democracy and transparent and accountable governance in all sectors of society are indispensable foundations for the realization of social and people-centered sustainable development. Articulated in a 1997 publication entitled, Governance for Sustainable Human Development: A UNDP Policy Document, it identifies the strength- ening of governing institutions – legislature, judiciary and electoral institutions – as one of five priority areas to support in order to best achieve corporate policy goals. -

LINEAGES of VOCAL PEDAGOGY in AUSTRALIA, 1850-1950 Volume 2

LINEAGES OF VOCAL PEDAGOGY IN AUSTRALIA, 1850-1950 Volume 2 by Beth Mary Williams A dissertation submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The University of Melbourne September 2002 11 Lineages of Vocal Pedagogy in Australia The following is an introductory lineage study of major lineages of vocal pedagogy in Australia. Many lineages not contained in the body of the thesis are outlined in this document. The lineage also provides a cursory glance at the major lineages of traditional Italian pedagogy which have relevance for an Australian vocal pedagogical context, and it was hoped that this might assist readers in ascertaining the long term lineage links without excessive complication. The symbol'-' indicates that the following is separated from what is immediately above, and that a new lineage has begun. Lineages are indicated as subsequent generations by the use of one tab space, to show that the following names are pupils of the aforementioned. Naturally, lists of students of particular teachers are far from complete, and some only represent one particularly successful pupil of a given teacher. Where possible dates and biographical information are given, in order to contextualise the work of a singer or teacher. The documentation of lineages is not exhaustive. Many teachers who were active between 1850 and 2000 are omitted owing to the difficulties in finding information on private studios through archival resources and the reluctance of many present teachers to participate in surveys. The following is a sample three-generation entry, with an explanation of how the lineage may be understood: ~ (Separates different schools of singers.) Joe Bloggs (The teacher/s of the following bold name.) Joe Green (The teacher/singer under consideration.) Tenor, born in 1889, Green performed extensively with the Eastside Liedertafel.