The Future of Security in Iraq's Nineveh Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KDP and Nineveh Plain

The Kurds and the Future of Nineveh Plain (Little Assyria) Fred Aprim December 7, 2006 It puzzles me how some of our people continue to misunderstand and misinterpret the simplest of behaviors or actions on the parts of Barazani's Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and those few Assyrian individuals who speak on behalf of the Assyrian nation unlawfully. Two simple questions: 1. If Mas'aud Barazani and KDP really mean well towards Assyrians, why marginalize the biggest Assyrian political group by far, i.e., the Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM) and exclude it from participating in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) cabinet since the ADM has been in that government since 1992 and won the only elections in northern Iraq that took place in that year. If the KDP means well, why use its influence in order to control the sole Iraqi Central Government seat that is assigned for ChaldoAssyrian Christians by having Fawzi Hariri, a KPD associate, as a minister in it. Why not act democratically and yield to the ADM that won in two national elections of January and December 2005 to fill that position? Why is it so hard to understand that Barazani is doing all this to control the Assyrians' future and cause? 2. Do the five Christian political groups, supported by KDP and its strong man Sargis Aghajan, that call for joining the Nineveh plains to the KRG, namely, a) Assyrian Patriotic Party (APP), b) ChaldoAshur Org. of Kurdistani Communist Party, c) Chaldean Democratic Forum (CDF), d) Chaldean Cultural Association (CCA), and e) Bet Nahrain Democratic Party (BNDP) really think that they will secure the Assyrian rights by simply allowing Barazani to usurp the Nineveh plain without serious guarantees recognized by the Iraqi government and international institutions. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

WFP Iraq Country Brief in Numbers

WFP Iraq Country Brief In Numbers November & December 2018 6,718 mt of food assistance distributed US$9.88 m cash-based transfers made US$58.8 m 6-month (February - July 2019) net funding requirements 516,741 people assisted WFP Iraq in November & December 2018 0 49% 51% Country Brief November & December 2018 Operational Updates Operational Context Operational Updates In April 2014, WFP launched an Emergency Programme to • Returns of displaced Iraqis to their areas of origin respond to the food needs of 240,000 displaced people from continue, with more than 4 million returnees and 1.8 Anbar Governorate. The upsurge in conflict and concurrent million internally displaced persons (IDPs) as of 31 downturn in the macroeconomy continue today to increase the December (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix). Despite poverty rate, threaten livelihoods and contribute to people’s the difficulties, 62 percent of IDPs surveyed in camp vulnerability and food insecurity, especially internally displaced settings by the REACH Multi Cluster Needs Assessment persons (IDPs), women, girls and boys. As the situation of IDPs (MCNA) VI indicated their intention to remain in the remains precarious and needs rise following the return process camps, due to lack of security, livelihoods opportunities that began in early 2018, WFP’s priorities in the country remain and services in their areas of origin. emergency assistance to IDPs, and recovery and reconstruction • Torrential rainfall affected about 32,000 people in activities for returnees. Ninewa and Salah al-Din in November 2018. Several IDP camps, roads and bridges were impacted by severe To achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in flooding, leading to a state of emergency being declared particular SDG 2 “Zero Hunger” and SDG 17 “Partnerships for the by authorities, and concerns about the long-term Goals”, WFP is working with partners to support Iraq in achieving viability of the Mosul Dam. -

MCC Service Opportunity ______

MCC Service Opportunity ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Assignment Title: Intensive English Program Teacher Term: 5 weeks (June 28 – August 1, 2015) FTE: 1 Location: Ankawa / Erbil, Iraq Start Date: Jun/28/2015 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ All MCC workers are expected to exhibit a commitment to: a personal Christian faith and discipleship; active church membership; and biblical nonviolent peacemaking. MCC is an equal opportunity employer, committed to employment equity. MCC values diversity and invites all qualified candidates to apply. Synopsis: The Chaldean Archdiocese of Erbil has asked MCC to provide a minimum of 3 and not more than 6 English teachers to teach English language skills to teachers, seminarians, nuns and members of the Chaldean community in Ankawa, Iraq. Three English language teachers will have primary responsibility for working together to teach English vocabulary, grammar and reading/listening and speaking/writing skills to Iraqi teachers at Mar Qardakh School. Additional teachers will provide English language instruction to members of the Chaldean community who are not teaching at Mar Qardakh School but who need to improve their English skills. Classes will be held each day, Sunday – Thursday, from 9:00 am – 12:30 PM. The program for students will begin on Sunday, July 5 and end on Thursday, July 30, 2015. Financial arrangements. The partner organization will cover food, lodging, travel to and from the assignment as well as work-related transportation. The short term teacher will cover all other expenses including visa costs, health insurance, medical costs and all personal expenses. Qualifications: 1. All MCC workers are expected to exhibit a commitment to a personal Christian faith and discipleship, active church membership, and nonviolent peacemaking. -

Blood and Ballots the Effect of Violence on Voting Behavior in Iraq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv DEPTARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BLOOD AND BALLOTS THE EFFECT OF VIOLENCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR IN IRAQ Amer Naji Master’s Thesis: 30 higher education credits Programme: Master’s Programme in Political Science Date: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Andreas Bågenholm Words: 14391 Abstract Iraq is a very diverse country, both ethnically and religiously, and its political system is characterized by severe polarization along ethno-sectarian loyalties. Since 2003, the country suffered from persistent indiscriminating terrorism and communal violence. Previous literature has rarely connected violence to election in Iraq. I argue that violence is responsible for the increases of within group cohesion and distrust towards people from other groups, resulting in politicization of the ethno-sectarian identities i.e. making ethno-sectarian parties more preferable than secular ones. This study is based on a unique dataset that includes civil terror casualties one year before election, the results of the four general elections of January 30th, and December 15th, 2005, March 7th, 2010 and April 30th, 2014 as well as demographic and socioeconomic indicators on the provincial level. Employing panel data analysis, the results show that Iraqi people are sensitive to violence and it has a very negative effect on vote share of secular parties. Also, terrorism has different degrees of effect on different groups. The Sunni Arabs are the most sensitive group. They change their electoral preference in response to the level of violence. 2 Acknowledgement I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

The Expulsion of Christians from Nineveh

Nasara The Expulsion of Christians from Nineveh Paul Kingery Introduction: Mosul is Iraq’s second largest city, the site of Biblical Nineveh where Jonah and Nahum preached, and where later, according to local tradition, Jesus’ Apostles Thomas and Judas (Thaddeus) brought the Aramaic language of Jesus and His teachings. They had many converts in the area. The church there preserved the language of Jesus into modern times. The ancient Assyrian villages near water sources in the surrounding arid lands also had many Christian converts by the second century despite the continued strong presence of Assyrian, Greek, and Zoroastrian religions. Most of the Assyrian temples were converted to Christian worship places. Early Christians there faced great persecution and many were killed for their faith, including Barbara, the daughter of the pagan governor of Karamles. One of the hills beside the city is named after her. Through the centuries priests came from various religious orders and divided Christians into several sects, some loyal to the Catholic tradition, others adhering to Eastern leadership. Mohammad began preaching Islam around 610 A.D., facing violent opposition to his teachings for twenty years from tribes in the area of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Even so, his movement grew in numbers and strength. In December 629, he gathered an army of 10,000 Muslim converts and invaded Mecca. The attack went largely uncontested and Muhammad seized the city (Sahih-Bukhari, Book 43, #658). His followers, increasingly radicalized, went on to invade other cities throughout Iraq and all the way to Europe, Africa, and Asia, giving the option of conversion or death. -

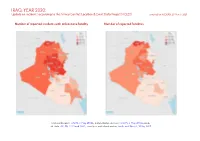

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 1795 13 36 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 1761 308 824 Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 2 violence Battles 869 502 1461 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 580 7 11 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 441 40 68 Violence against civilians 408 239 315 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5854 1109 2715 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Iraq - CCCM Camps Status Report As of 19 May 2015

Iraq - CCCM Camps status report As of 19 May 2015 Key information Distribution of IDP Camp in Iraq Dahuk 1 10 1 Diyala 3 3 1 TOTAL Iraqs 239 440 Baghdad 4 2 Ninewa 5 1 Erbil 3 1 Sulaymaniyah 1 2 Kirkuk 2 1 TOTAL KRI Region of Iraq 209 603 Basrah 1 1 Najaf 1 Salah al-Din 1 Wassit 1 Missan 1 TOTAL Centre and South Iraq 29 837 Babylon 1 Kerbala 1 Closed open Under Construction IDPs in Kurdistan Region* of Iraq Current Planned capacity Plots Construction lead / # Governorate District Camp population Camp management Status individuals Available Shelter Care individuals TOTAL KRI Region of Iraq 209 603 232 707 4 288 Dahuk 142 554 151 082 1 522 UNHCR/KURDS/Dohu 1 Dahuk Sumel Bajet Kandala 12 721 12 000 1 522 Dohuk Governorate open k Governorate Dohuk 2 Dahuk Sumel Kabarto 1 14 067 12 000 - Dohuk Governorate governorate/Artosh open company Dohuk 3 Dahuk Sumel Kabarto 2 14 122 - - Dohuk Governorate Governorate/Doban open and Shahan company 4 Dahuk Sumel Khanke 18 165 21 840 - Dohuk Governorate UNHCR/KURDS open 5 Dahuk Sumel Rwanga Community 14 775 16 000 - Dohuk Governorate open 6 Dahuk Sumel Shariya 18 699 28 000 - Dohuk Governorate open AFAD/Dohuk 7 Dahuk Zakho Berseve 1 11 242 15 000 - Dohuk Governorate open Governorate 8 Dahuk Zakho Berseve 2 9 336 10 920 - Dohuk Governorate UNHCR/PWJ open 9 Dahuk Zakho Chamishku 25 318 30 000 - Dohuk Governorate Dohuk Governorate open 10 Dahuk Zakho Darkar - - - UN-Habitat Under Construction HABITAT / IOM / 11 Dahuk Zakho Dawadia 4 109 5 322 - Dohuk Governorate open UNDP 12 Dahuk Zakho Wargahe Zakho - - - -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Perché La Fede Dà Speranza « Rapporto Attività 2019

dal 1947 con i Cristiani perseguitati » Perché la fede dà speranza « Rapporto Attività 2019 ACS Rapporto Attività 2019 | 1 Cari amici e benefattori, a buon diritto dobbiamo considerare il ritornano nei loro paesi e nelle loro città. 2019 un anno di martirio. Gli attentati dina- Anche quest’anno migliaia di ragazzi in tutto mitardi avvenuti nello Sri Lanka il giorno il mondo – e questo è motivo di grande di Pasqua in tre chiese e in diversi hotel speranza per l’evangelizzazione – hanno e costati la vita a oltre 250 persone, sono potuto continuare il loro percorso verso il stati il triste culmine di un sanguinoso cal- sacerdozio. Innumerevoli religiosi e religiose vario che i cristiani in molti Paesi al mondo nelle zone di guerra, nelle baraccopoli delle hanno dovuto percorrere. metropoli, nelle aree impervie delle regioni montuose o nella foresta vergine sono La nostra preoccupazione è stata acuita riusciti a continuare a rendere i loro servigi soprattutto dalla situazione di molti Paesi eroici ai più poveri, senza tener conto della africani, in cui il jahidismo in sensibile propria vita. In Russia la collaborazione aumento è diventato una minaccia cre- promossa da ACS, basata sulla fiducia, tra la scente per i cristiani. Quest’anno è stata di Chiesa cattolica e quella russo-ortodossa ha particolare preoccupazione la situazione prodotto nuovi frutti. drammatica nel Burkina Faso. Però anche il Medio Oriente, culla della cristianità, Rendo grazie a Dio anche a nome di tutti continua ad essere in pericolo. coloro che, con il vostro sostegno, sono stati incoraggiati, confortati e messi in condi- Tuttavia queste notizie non devono scorag- zione di diventare un segno di speranza per giarci.