The Plymouth Athenæum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

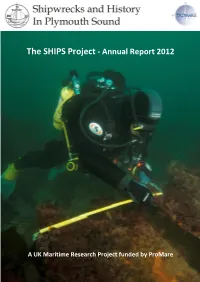

Annual Report 2012

The SHIPS Project - Annual Report 2012 A UK Maritime Research Project funded by ProMare 1 SHIPS Project Report 2012 ProMare President and Chief Archaeologist Dr. Ayse Atauz Phaneuf Project Manager Peter Holt Foreword The SHIPS Project has a long history of exploring Plymouth Sound, and ProMare began to support these efforts in 2010 by increasing the fieldwork activities as well as reaching research and outreach objectives. 2012 was the first year that we have concentrated our efforts in investigating promising underwater targets identified during previous geophysical surveys. We have had a very productive season as a result, and the contributions that our 2012 season’s work has made are summarized in this document. SHIPS can best be described as a community project, and the large team of divers, researchers, archaeologists, historians, finds experts, illustrators and naval architects associated with the project continue their efforts in processing the information and data that has been collected throughout the year. These local volunteers are often joined by archaeology students from the universities in Exeter, Bristol and Oxford, as well as hydrography and environmental science students at Plymouth University. Local commercial organisations, sports diving clubs and survey companies such as Swathe Services Ltd. and Sonardyne International Ltd. support the project, particularly by helping us create detailed maps of the seabed and important archaeological sites. I would like to say a big ‘thank you’ to all the people who have helped us this year, we could not do it without you. Dr. Ayse Atauz Phaneuf ProMare President and Chief Archaeologist ProMare Established in 2001 to promote marine research and exploration throughout the world, ProMare is a non-profit corporation and public charity, 501(c)(3). -

Trojans at Totnes and Giants on the Hoe: Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historical Fiction and Geographical Reality

Rep. Trans. Devon. Ass. Advmt Sci., 148, 89−130 © The Devonshire Association, June 2016 (Figures 1–8) Trojans at Totnes and Giants on the Hoe: Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historical Fiction and Geographical Reality John Clark MA, FSA, FMA Curator Emeritus, Museum of London, and Honorary Reader, University College London Institute of Archaeology Geoffrey of Monmouth’s largely fi ctional History of the Kings of Britain, written in the 1130s, set the landing place of his legendary Trojan colonists of Britain with their leader Brutus on ‘the coast of Totnes’ – or rather, on ‘the Totnesian coast’. This paper considers, in the context of Geoffrey’s own time and the local topography, what he meant by this phrase, which may refl ect the authority the Norman lords of Totnes held over the River Dart or more widely in the south of Devon. We speculate about the location of ‘Goemagot’s Leap’, the place where Brutus’s comrade Corineus hurled the giant Goemagot or Gogmagog to his death, and consider the giant fi gure ‘Gogmagog’ carved in the turf of Plymouth Hoe, the discovery of ‘giants’ bones’ in the seventeenth century, and the possible signifi cance of Salcombe’s red-stained rocks. THE TROJANS – AND OTHERS – IN DEVON Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) was completed in about 1136, and quickly became, in medieval terms, a best-seller. To all appearance it comprised what ear- lier English historians had said did not exist – a detailed history of 89 DDTRTR 1148.indb48.indb 8899 004/01/174/01/17 111:131:13 AAMM 90 Trojans at Totnes Britain and its people from their beginnings right up to the decisive vic- tory of the invading Anglo-Saxons in the seventh century AD. -

The Lees of Quethiock Cornwall Their Family History from Ancient Times

THE LEES OF QUETHIOCK CORNWALL THEIR FAMILY HISTORY FROM ANCIENT TIMES "Brave men have lived before Agamemnon, lots of them. But on all of them - eternal night lies heavy, for they left no records behind. (`ODES` Horace 65-8BC) This is the story of those who did This is the story of my ancestors, the Lee family, who have left records behind and from which the line can be traced from Alexander and Thomas born 1994 and 1990 respectively, back to John of Legh, alive in 1433, and Richard de Leye, alive in 1327. John and Richard lived at, and took their surname from Legh, a pre-Norman settlement in Cornwall recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. Legh is situated in the present parish of Quethiock, some 5 miles west of the River Tamar and 5 miles east of Liskeard, just in the southeast corner of Cornwall. To uncover the history took ten and more years of research. So what stimulated me to commence? In 1986 I watched a television programme on early portraiture. It was explained that during the time of the Roman Empire (146BC-410AD) it was fashionable to have a statue carved of oneself together with ones father and grandfather. To illustrate this a statue from the 1st century AD was shown; I was astounded to note that it bore a likeness to my family and in particular to my brother, David Henry Lee. I immediately commented on this to my wife, Brenda, who replied `No, it is more like you`. From that moment the question lay in my mind `I look like a Roman from 2000 years ago; I have the surname of Lee which is derived from a Saxon-German word meaning pasture; my father`s family were known to have come from Cornwall and so presumably I have West Welsh Celtic blood; my mother claimed her family came from Devon and I was born in Devonport on the borders of Devon and Cornwall; so who am I? Cornwall over the millenniums had been invaded by 6 or so groups of different people; Ancient British (7000BC), Celts (700BC-63AD), Danes (800AD), Romans (63-401AD), Saxons (447-1066AD), Normans (1066). -

Digitalcommons@URI

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 2014 “BY GOODLY RIVER'S UNINHABITED” WATERWAYS AND PLYMOUTH COLONY Jordan Coulobme University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Coulobme, Jordan, "“BY GOODLY RIVER'S UNINHABITED” WATERWAYS AND PLYMOUTH COLONY" (2014). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 439. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/439 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “BY GOODLY RIVER'S UNINHABITED” WATERWAYS AND PLYMOUTH COLONY BY JORDAN COULOMBE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2014 MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY THESIS OF JORDAN COULOMBE APPROVED: Thesis Committee: Major Professor Erik Loomis Timothy George Kristine Bovy Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2014 Abstract The colonists of Plymouth were dependent on aquatic environments for the dispersal and acquisition of ideas, goods, and people. This thesis builds on of the work of Donald Worster and Michael Rawson amongst others to examine the importance of water in Plymouth Colony. Ultimately this study utilizes primary documents to argue that the abundance of aquatic environments in the colonies played a crucial role in allowing for the establishment of a permanent colony in New England. The rise of environmental history over the past several decades presents a natural tool for analyzing the experiences of Plymouth's earliest settlers. -

ABSTRACT HAMMERSEN, LAUREN ALEXANDRA MICHELLE. The

ABSTRACT HAMMERSEN, LAUREN ALEXANDRA MICHELLE. The Control of Tin in Southwestern Britain from the First Century AD to the Late Third Century AD. (Under the direction of Dr. S. Thomas Parker.) An accurate understanding of how the Romans exploited mineral resources of the empire is an important component in determining the role Romans played in their provinces. Tin, both because it was extremely rare in the ancient world and because it remained very important from the first to third centuries AD, provides the opportunity to examine that topic. The English counties of Cornwall and Devon were among the few sites in the ancient world where tin was found. Archaeological evidence and ancient historical sources prove tin had been mined extensively in that region for more than 1500 years before the Roman conquest. During the period of the Roman occupation of Britain, tin was critical to producing bronze and pewter, which were used extensively for both functional and decorative items. Despite the knowledge that tin was found in very few places, that tin had been mined in the southwest of Britain for centuries before the Roman invasion, and that tin remained essential during the period of the occupation, for more than eighty years it has been the opinion of historians such as Aileen Fox and Sheppard Frere that the extensive tin mining of the Bronze Age was discontinued in Roman Britain until the late third or early fourth centuries. The traditional belief has been that the Romans were instead utilizing the tin mines of Spain (i.e., the Roman province of Iberia). -

Memorials to World War II Civilians

Memorials to World War II civilians Introduction Tens of thousands of UK civilians died during World War II. Many of these were casualties of air raids during the Blitz in 1940 and 1941, with residents of London, Birmingham, Coventry, Liverpool and Glasgow among those particularly badly affected. Included in the count of civilian deaths are members of the Civil Defence Service (such as air raid wardens) and Women’s Voluntary Service killed on duty. War memorials remember all those killed or affected by war, and many memorials to the war dead include civilians as well as military personnel. Some other memorials have been created specifically to remember civilians killed in World War II. This information sheet gives details of some of these memorials that commemorate civilians and the events that affected those people, and can be used in conjunction with WMT’s lessons about World War II. Memorials in London Around 20,000 London civilians lost their lives as a result of enemy action during World War II. Many of these were victims of air raids during the Blitz, a period of concentrated bombing of the UK’s cities and industrial areas in 1940-41, which began on 7th September 1940 with raids over London. As well as ordinary civilians, people doing non- military war work such as firefighters and air raid wardens were affected. These people are remembered on a number of war memorials in the city. People of London memorial The memorial to the people of London killed during World War II consists of a circular block of stone, on the top of which is inscribed, in a circular pattern, ‘In war resolution, in defeat defiance, in victory magnanimity, in peace goodwill.’ Around the side of the stone is a further inscription: ‘Remember before God the people of London 1939-1945.’ The memorial was unveiled in 1995 to coincide with the 50th anniversary of VE Day and remembers all Londoners who lost their lives during the war. -

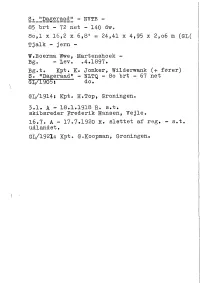

85 Brt - 72 Net - 140 Dw

S^o^^Dageraad*^ - WVTB - 85 brt - 72 net - 140 dw. 8o,l x 16,2 x 6,8' = 24,41 x 4,95 x 2,o6 m (GL( Tjalk - jern - W.Boerma Wwe, Martenshoek - Bg. - lev. .4.1897. Bg.t. Kpt. Ko Jonker, Wilderwank (+ fører) S. "Dageraad" - NLTQ - 8o brt - 67 net GI/1905: do. GL/1914: KptO H.Top, Groningen. 3.1. A - 18.1.1918 R. s.t. skibsreder Frederik Hansen, Vejle, 16.7. A - 17.7.1920 R. slettet af reg. - s.t. udlandet. Gl/1921: Kpt. G.Koopman, Groningen. ^Dagmar^ - HBKN - , 187,81 hrt - 181/173 NRT - E.C. Christiansen, Flenshurg - 1856, omhg. Marstal 1871. ex "Alma" af Marstal - Flb.l876$ C.C.Black, Marstal. 17.2.1896: s.t. Island - SDagmarS - NLJV - 292,99 brt - 282 net - lo2,9 x 26,1 x 14,1 (KM) Bark/Brig - eg og fyr - 1 dæk - hækbg. med fladt spejl - middelf. bov med glat stævn. Bg. Fiume - 1848 - BV/1874: G. Mariani & Co., Fiume: "Fidente" - 297 R.T. 29.8.1873 anrn. s.t. partrederi, Nyborg - "DagmarS - Frcs. 4o.5oo mægler Hans Friis (Møller) - BR 4/24, konsul H.W. Clausen - BR fra 1875 6/24 købm. CF. Sørensen 4/24 " Martin Jensen 4/24 skf. C.J. Bøye 3/24 skf. B.A. Børresen - alle Nyborg - 3/24 29.12.1879: Forlist p.r. North Shields - Tuborg havn med kul - Sunket i Kattegat ca. 6 mil SV for Kråkan, da skibet ramtes af brådsø, der knækkede alle støtter, ramponerede skibets ene side, knuste båden og ødelagde pumperne. -

A Brief History of the Cornish Language, Its Revival and Its Current Status Siarl Ferdinand University of Wales Trinity Saint David

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 2 Cultural Survival Article 6 12-2-2013 A Brief History of the Cornish Language, its Revival and its Current Status Siarl Ferdinand University of Wales Trinity Saint David Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Ferdinand, Siarl (2013) "A Brief History of the Cornish Language, its Revival and its Current Status," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol2/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. A Brief History of the Cornish Language, its Revival and its Current Status Siarl Ferdinand, University of Wales Trinity Saint David Abstract Despite being dormant during the nineteenth century, the Cornish language has been recently recognised by the British Government as a living regional language after a long period of revival. The first part of this paper discusses the history of traditional Cornish and the reasons for its decline and dismissal. The second part offers an overview of the revival movement since its beginnings in 1904 and analyses the current situation of the language in all possible domains. -

The Atlantic Project Guide.Pdf

THE PROJECT After The Future 28 September – 21 October 2018 THE PROJECT After The Future 28 September – 21 October 2018 Artists: Nilbar Güreş, Tommy Støckel, Liu Chuang, Yan Wang Preston, Hito Steyerl, Vermeir & Heiremans, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Donald Rodney, Shezad Dawood, Postcommodity, Ryoji Ikeda, Carl Slater, SUPERFLEX, Uriel Orlow, Jane Grant & John Matthias, Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll & Keren Ruki, Chang Jia, Ursula Biemann, Bryony Gillard, Kranemann + Emmett Curated by Tom Trevor 1 Publication + Colophon Contents Contents This book is published on the 4 Introduction occasion of The Atlantic Project 6 Curatorial Statement (28 September – 21 October 2018). 8 Sites & Artists The Atlantic Project 10 Armada Way c/o The Arts Institute University of Plymouth 14 House of Fraser Drake Circus 20 Civic Centre Plymouth PL4 8AA United Kingdom 30 Council House 34 The Dome +44 (0) 1752 584 980 [email protected] 38 Drake’s Island www.theatlantic.org 42 Millennium Building 48 The Clipper 52 KARST 56 Royal William Yard 66 National Marine Aquarium 72 Immersive Vision Theatre 76 Atlantic Platform 80 Events 94 Events Diary 96 Atlantic Project Team 98 Acknowledgements 102 Map CULTURE 2 3 Introduction New Art and New Ideas Horizon The Atlantic Project is a pilot for a new The visual arts in Plymouth are international festival of contemporary art undergoing an exciting period in the South West of England, taking place of change, in the lead-up to the in public contexts and outdoor locations Mayflower 400 anniversary in 2020. across Plymouth, from 28 September 2018. Building on a decade of collaboration between exhibition venues, the Horizon programme is a two-year city-wide Led by Tom Trevor (Artistic Director), the project has development programme (2016-18), led by Plymouth been developed as a core partnership between The Box Culture, which aims to grow the whole of the visual arts (formerly Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery) and the ecology. -

Making Soap in Plymouth

Making Soap in Plymouth Dr James Gregory, Department of History, University of Plymouth May 2020 e.mail: [email protected] That the consumption of Soap in England does not increase with population, wealth, commerce, or civilisation of the nation. That the people of England, high and low, consume a less average quality of Soap per head than they allow the convicts in the 1 prisons, or the paupers in the workhouses. Who can deny my claim? Health’s truest friend, I cleanse the skin of rich and poor alike: Disease flies from me, as from mortal foe, From kingly palace down to cottage hearth, Are constant records of my service found. Each garment worn, by king, queen, knight, or peasant, 2 Bears witness of my power, my wondrous power. As these two quotations indicate, soap stimulated some controversy in England in the first half of the nineteenth century, before the tax which had long been imposed on this important commodity was removed by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Gladstone, in 1853. This meant that English manufacturers were in competition with Irish soap-makers who did not have the tax. Into the early 1840s, soap makers were subject to regulations which controlled the shape and size of soap bars, the ingredients, the methods of boiling, and the specific gravities of the 1 Western Courier, 29 November 1849. 2 Western Courier, 19 February 1851. The soap industry is referred to in previously published local histories such as C. Gill, Plymouth a New History: 1603 to the Present Day (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1979); see also the recent E. -

Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain

Material Cultures of Childhood in Second World War Britain How do children cope when their world is transformed by war? This book draws on memory narratives to construct an historical anthropology of childhood in Second World Britain, focusing on objects and spaces such as gas masks, air raid shelters and bombed-out buildings. In their struggles to cope with the fears and upheavals of wartime, with families divided and familiar landscapes lost or transformed, children reimagined and reshaped these material traces of conflict into toys, treasures and playgrounds. This study of the material worlds of wartime childhood offers a unique viewpoint into an extraordinary period in history with powerful resonances across global conflicts into the present day. Gabriel Moshenska is Associate Professor in Public Archaeology at University College London, UK. Material Culture and Modern Conflict Series editors: Nicholas J. Saunders, University of Bristol, Paul Cornish, Imperial War Museum, London Modern warfare is a unique cultural phenomenon. While many conflicts in history have produced dramatic shifts in human behaviour, the industrialized nature of modern war possesses a material and psychological intensity that embodies the extremes of our behaviours, from the total economic mobiliza- tion of a nation state to the unbearable pain of individual loss. Fundamen- tally, war is the transformation of matter through the agency of destruction, and the character of modern technological warfare is such that it simulta- neously creates and destroys more than any previous kind of conflict. The material culture of modern wars can be small (a bullet, machine-gun or gas mask), intermediate (a tank, aeroplane, or war memorial), and large (a battleship, a museum, or an entire contested landscape).