What Does the Snake Eat? Breadth, Overlap, and Non-Native Prey in the Diet of Three Sympatric Natricine Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Diversity of Snakes in Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve

& Herpeto gy lo lo gy o : h C it u n r r r e O Fellows, Entomol Ornithol Herpetol 2014, 4:1 n , t y R g e o l s o e Entomology, Ornithology & Herpetology: DOI: 10.4172/2161-0983.1000136 a m r o c t h n E ISSN: 2161-0983 Current Research ResearchCase Report Article OpenOpen Access Access Species Diversity of Snakes in Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve Sandeep Fellows* Asst Conservator of forest, Madhya Pradesh Forest Department (Information Technology Wing), Satpura Bhawan, Bhopal (M.P) Abstract Madhya Pradesh (MP), the central Indian state is well-renowned for reptile fauna. In particular, Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve (PBR) regions (Districts Hoshangabad, Betul and Chindwara) of MP comprises a vast range of reptiles, especially herpetofauna yet unexplored from the conservation point of view. Earlier inventory herpetofaunal study conducted in 2005 at MP and Chhattisgarh (CG) reported 6 snake families included 39 species. After this preliminary report, no literature existing regarding snake diversity of this region. This situation incited us to update the snake diversity of PBR regions. From 2010 to 2012, we conducted a detailed field study and recorded 31 species of 6 snake families (Boidae, Colubridae, Elapidae, Typhlopidea, Uropeltidae, and Viperidae) in Hoshanagbad District (Satpura Tiger Reserve) and PBR regions. Besides, we found the occurrence of Boiga forsteni and Coelognatus helena monticollaris (Colubridae), which was not previously reported in PBR region. Among the recorded, 9 species were Lower Risk – least concerned (LR-lc), 20 were of Lower Risk – near threatened (LR-nt), 1 is Endangered (EN) and 1 is vulnerable (VU) according to International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) status. -

Herpetological Journal SHORT NOTE

Volume 28 (April 2018), 93-95 SHORT NOTE Herpetological Journal Published by the British Intersexuality in Helicops infrataeniatus Jan, 1865 Herpetological Society (Dipsadidae: Hydropsini) Ruth A. Regnet1, Fernando M. Quintela1, Wolfgang Böhme2 & Daniel Loebmann1 1Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Laboratório de Vertebrados. Av. Itália km 8, CEP: 96203-900, Vila Carreiros, Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 2Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum A. Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany Herein, we describe the first case of intersexuality in the are viviparous, and interestingly, H. angulatus exhibits Hydropsini tribe. After examination of 720 specimens both reproductive modes (Rossman, 1984; Aguiar & Di- of Helicops infrataeniatus Jan, 1865, we discovered Bernardo, 2005; Braz et al., 2016). Helicops infrataeniatus one individual that presented feminine and masculine has a wide distribution that encompasses south- reproductive features. The specimen was 619 mm long, southeastern Brazil, southern Paraguay, North-eastern with seven follicles in secondary stage, of different shapes Argentina and Uruguay (Deiques & Cechin, 1991; Giraudo, and sizes, and a hemipenis with 13.32 and 13.57 mm in 2001; Carreira & Maneyro, 2013). At the coastal zone of length. The general shape of this organ is similar to that southernmost Brazil, H. infrataeniatus is among the most observed in males, although it is smaller and does not abundant species in many types of limnic and estuarine present conspicuous spines along its body. Deformities environments (Quintela & Loebmann, 2009; Regnet found in feminine and masculine structures suggest that et al., 2017). In October 2015 at the Laranjal beach, this specimen might not be reproductively functional. municipality of Pelotas, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (31°46’S, 52°13’W), a remarkable aggregation of reptiles Key words: Follicles, hemipenis, hermaphroditism, water and caecilians occurred after a flood event associated to snake. -

Behavioural And.Pdf

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 29 (2): 211–215, 2018 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it doi:10.4404/hystrix–00119-2018 Research Article Behavioural and population responses of ground-dwelling rodents to forest edges Maria Vittoria Mazzamuto∗, Lucas A. Wauters, Damiano G. Preatoni, Adriano Martinoli Environment Analysis and Management Unit, Guido Tosi Research Group, Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, via J.-H. Dunant 3, 21100 Varese, Italy Keywords: Abstract bank vole wood mouse Forest edges can affect the behaviour, physiology and demography of small mammals. We tested survival whether there was a response in abundance, distribution, personality selection or foraging behaviour seed predation of ground-dwelling rodents to a forest–meadow edge in two study areas in Northern Italy over a 1- personality year period. We used capture-mark-recapture to evaluate species distribution, abundance, survival GUD and personality, while Giving-up Density was used to test their foraging behaviour and the cost associated to it. All tests were carried out on the forest edge and at 50 and 100 m from the edge along Article history: three parallel transects 90 m long. We detected two species in both areas: Apodemus sylvaticus Received: 8/06/2018 and Myodes glareolus. We found a neutral effect of the edge on species number, survival and on Accepted: 3/12/2018 individual’s personality (activity/exploration tendency). Bank voles occurred more along the edge and both taxa took more seeds from trays along the edge. The hypothesis of edge avoidance was not Acknowledgements confirmed in any of the variables examined. -

Herpetofaunistic Diversity of the Cres-Lošinj Archipelago (Croatian Adriatic)

University of Sopron Roth Gyula Doctoral School of Forestry and Wildlife Management Sciences Ph.D. thesis Herpetofaunistic diversity of the Cres-Lošinj Archipelago (Croatian Adriatic) Tamás Tóth Sopron 2018 Roth Gyula Doctoral School of Forestry and Wildlife Management Sciences Nature Conservation Program Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Faragó Sándor Dr. Gál János Introduction In recent years the Croatian islands, especially those of the Cres-Lošinj Archipelago became the focus of research of herpetologists. However, in spite of a long interest encompassing more than a hundred years, numerous gaps remain in our herpetological knowledge. For this reason, the author wished to contribute to a better understanding by performing studies outlined below. Aims The first task was to map the distribution of amphibians and reptiles inhabiting the archipelago as data were lacking for several of the smaller islands and also the fauna of the bigger islands was insufficiently known. Subsequently, the faunistic information derived from the scientific literature and field surveys conducted by the author as well as available geological and paleogeological data were compared and analysed from a zoogeographic point of view. The author wished to identify regions of the islands boasting the greatest herpetofaunal diversity by creating dot maps based on collecting localities. To answer the question which snake species and which individuals are going to be a victim of the traffic snake roadkill and literature survey were used. The author also identified where are the areas where the most snakes are hit by a vehicle on Cres. By gathering road-killed snakes and comparing their locality data with published occurrences the author seeked to identify species most vulnerable to vehicular traffic and road sections posing the greatest threat to snakes on Cres Island. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Reptiles in and Around the House Identification and Distribution Reptiles Inhabit Every Environment in Australia

Reptiles in and around the house Identification and Distribution Reptiles inhabit every environment in Australia. Common reptiles found in Western Australian backyards include: Tiger snakes Notechis scutatus occur in southwest WA, and are often seen near water, including rivers, dams, drains and wetlands. Unlike most other Australian elapids, tiger snakes climb well. They can range from grey, olive, brown to black in colour and often have yellow and black cross-bands, but not all have this pattern. Venomous Dugite. Photo: R. Lloyd/Fauna Track Dugites Pseudonaja affinis occur in southwest WA and Gwarda Pseudonaja nuchalis occur from Perth northwards. They live in a wide variety of habitats including coastal dunes, heathlands, shrublands, woodlands and forests. They are long and slender, with relatively large scales that have a semi-glossy appearance. They can range from brown, olive to grey in colour, and can have irregular black/dark grey spotting, but patterning varies. Venomous Mulga snakes Pseudechis australis occur in a wide variety of habitats, northwards from Perth and Narrogin. They are quite robust, with a broad, deep head and bulbous cheeks. They can range from pale brown, dark olive to reddish-brown in colour, and darker snakes often have two-toned scales with a lighter colour that contrasts with the darker colour to produce a reticulated effect. The belly is cream to salmon-coloured. Venomous There are two subspecies of carpet pythons found in a large variety of habitats in WA: Morelia spilota imbricata occurs in the southwest and Morelia spilota variegata occurs in the Kimberley. They are 1-4m in length, tend to be pale to dark brown with black blotches that sometimes have a Carpet python. -

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

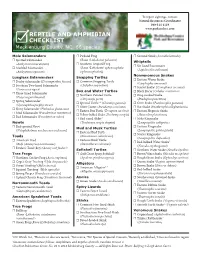

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Venemous Snakes

WASAH WESTERN AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY of AMATEUR HERPETOLOGISTS (Inc) K E E P I N G A D V I C E S H E E T Venomous Snakes Southern Death Adder (Acanthophis Southern Death antarcticus) – Maximum length 100 cm. Adder Category 5. Desert Death Adder (Acanthophis pyrrhus) – Acanthophis antarcticus Maximum length 75 cm. Category 5. Pilbara Death Adder (Acanthophis wellsi) – Maximum length 70 cm. Category 5. Western Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) - Maximum length 160 cm. Category 5. Mulga Snake (Pseudechis australis) – Maximum length 300 cm. Category 5. Spotted Mulga Snake (Pseudechis butleri) – Maximum length 180 cm. Category 5. Dugite (Pseudonaja affinis affinis) – Maximum Desert Death Adder length 180 cm. Category 5. Acanthophis pyrrhus Gwardar (Pseudonaja nuchalis) – Maximum length 100 cm. Category 5. NOTE: All species listed here are dangerously venomous and are listed as Category 5. Only the experienced herpetoculturalist should consider keeping any of them. One must be over 18 years of age to hold a category 5 license. Maintaining a large elapid carries with 1 it a considerable responsibility. Unless you are Pilbara Death Adder confident that you can comply with all your obligations and licence requirements when Acanthophis wellsi keeping dangerous animals, then look to obtaining a non-venomous species instead. NATURAL HABITS: Venomous snakes occur in a wide variety of habitats and, apart from death adders, are highly mobile. All species are active day and night. HOUSING: In all species listed except death adders, one adult (to 150 cm total length) can be kept indoors in a lockable, top-ventilated, all glass or glass-fronted wooden vivarium of Western Tiger Snake at least 90 x 45 cm floor area. -

Does Urbanization Influence the Diet of a Large Snake?

Current Zoology, 2018, 64(3), 311–318 doi: 10.1093/cz/zox039 Advance Access Publication Date: 27 June 2017 Article Article Does urbanization influence the diet of a large snake? a, a b Ashleigh K. WOLFE *, Philip W. BATEMAN , and Patricia A. FLEMING aDepartment of Environment and Agriculture, Curtin University, Perth, Bentley, WA, 6102, Australia and bSchool of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, Perth, Murdoch, WA, 6150, Australia *Address correspondence to Ashleigh K. Wolfe. E-mail: [email protected] Received on 10 April 2017; accepted on 21 May 2017 Abstract Urbanization facilitates synanthropic species such as rodents, which benefit the diets of many preda- tors in cities. We investigated how urbanization affects the feeding ecology of dugites Pseudonaja affi- nis, a common elapid snake in south-west Western Australia. We predicted that urban snakes: 1) more frequently contain prey and eat larger meals, 2) eat proportionally more non-native prey, 3) eat a lower diversity of prey species, and 4) are relatively heavier, than non-urban dugites. We analyzed the diet of 453 specimens obtained from the Western Australian Museum and opportunistic road-kill collections. Correcting for size, sex, season, and temporal biases, we tested whether location influenced diet for our 4 predictions. Body size was a strong predictor of diet (larger snakes had larger prey present, a greater number of prey items, and a greater diversity of prey). We identified potential collection biases: urban dugites were relatively smaller (snout-vent length) than non-urban specimens, and females were relatively lighter than males. Accounting for these effects, urban snakes were less likely to have prey present in their stomachs and were relatively lighter than non-urban snakes. -

211356675.Pdf

306.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE STORERIA DEKA YI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and western Honduras. There apparently is a hiatus along the Suwannee River Valley in northern Florida, and also a discontin• CHRISTMAN,STEVENP. 1982. Storeria dekayi uous distribution in Central America . • FOSSILRECORD. Auffenberg (1963) and Gut and Ray (1963) Storeria dekayi (Holbrook) recorded Storeria cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean (pleisto• Brown snake cene) of Florida, and Holman (1962) listed S. cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean of Texas. Storeria sp. is reported from the Ir• Coluber Dekayi Holbrook, "1836" (probably 1839):121. Type-lo• vingtonian and Rancholabrean of Kansas (Brattstrom, 1967), and cality, "Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Louisiana"; the Rancholabrean of Virginia (Guilday, 1962), and Pennsylvania restricted by Trapido (1944) to "Massachusetts," and by (Guilday et al., 1964; Richmond, 1964). Schmidt (1953) to "Cambridge, Massachusetts." See Re• • PERTINENT LITERATURE. Trapido (1944) wrote the most marks. Only known syntype (Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia complete account of the species. Subsequent taxonomic contri• 5832) designated lectotype by Trapido (1944) and erroneously butions have included: Neill (195Oa), who considered S. victa a referred to as holotype by Malnate (1971); adult female, col• lector, and date unknown (not examined by author). subspecies of dekayi, Anderson (1961), who resurrected Cope's C[oluber] ordinatus: Storer, 1839:223 (part). S. tropica, and Sabath and Sabath (1969), who returned tropica to subspecific status. Stuart (1954), Bleakney (1958), Savage (1966), Tropidonotus Dekayi: Holbrook, 1842 Vol. IV:53. Paulson (1968), and Christman (1980) reported on variation and Tropidonotus occipito-maculatus: Holbrook, 1842:55 (inserted ad- zoogeography. Other distributional reports include: Carr (1940), denda slip). -

Ecological Functions of Neotropical Amphibians and Reptiles: a Review

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 229-245 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.efna Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Ecological functions of neotropical amphibians and reptiles: a review Cortés-Gomez AM1, Ruiz-Agudelo CA2 , Valencia-Aguilar A3, Ladle RJ4 Abstract Amphibians and reptiles (herps) are the most abundant and diverse vertebrate taxa in tropical ecosystems. Nevertheless, little is known about their role in maintaining and regulating ecosystem functions and, by extension, their potential value for supporting ecosystem services. Here, we review research on the ecological functions of Neotropical herps, in different sources (the bibliographic databases, book chapters, etc.). A total of 167 Neotropical herpetology studies published over the last four decades (1970 to 2014) were reviewed, providing information on more than 100 species that contribute to at least five categories of ecological functions: i) nutrient cycling; ii) bioturbation; iii) pollination; iv) seed dispersal, and; v) energy flow through ecosystems. We emphasize the need to expand the knowledge about ecological functions in Neotropical ecosystems and the mechanisms behind these, through the study of functional traits and analysis of ecological processes. Many of these functions provide key ecosystem services, such as biological pest control, seed dispersal and water quality. By knowing and understanding the functions that perform the herps in ecosystems, management plans for cultural landscapes, restoration or recovery projects of landscapes that involve aquatic and terrestrial systems, development of comprehensive plans and detailed conservation of species and ecosystems may be structured in a more appropriate way. Besides information gaps identified in this review, this contribution explores these issues in terms of better understanding of key questions in the study of ecosystem services and biodiversity and, also, of how these services are generated. -

Indigenous Reptiles

Reptiles Sylvain Ursenbacher info fauna & NLU, Universität Basel pdf can be found: www.ursenbacher.com/teaching/Reptilien_UNIBE_2020.pdf Reptilia: Crocodiles Reptilia: Tuataras Reptilia: turtles Rep2lia: Squamata: snakes Rep2lia: Squamata: amphisbaenians Rep2lia: Squamata: lizards Phylogeny Tetrapoda Synapsida Amniota Lepidosauria Squamata Sauropsida Anapsida Archosauria H4 Phylogeny H5 Chiari et al. BMC Biology 2012, 10:65 Amphibians – reptiles - differences Amphibians Reptiles numerous glands, generally wet, without or with limited number skin without scales of glands, dry, with scales most of them in water, no links with water, reproduction larval stage without a larval stage most of them in water, packed in not in water, hard shell eggs tranparent jelly (leathery or with calk) passive transmission of venom, some species with active venom venom toxic skin as passive protection injection Generally in humide and shady Generally dry and warm habitats areas, nearby or directly in habitats, away from aquatic aquatic habitats habitats no or limited seasonal large seasonal movements migration movements, limited traffic inducing big traffic problems problems H6 First reptiles • first reptiles: about 320-310 millions years ago • embryo is protected against dehydration • ≈ 305 millions years ago: a dryer period ➜ new habitats for reptiles • Mesozoic (252-66 mya): “Age of Reptiles” • large disparition of species: ≈ 252 and 65 millions years ago H7 Mesozoic Quick systematic overview total species CH species (oct 2017) Order Crocodylia (crocodiles)