For Peer Review Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRENT APPLIED PHYSICS "Physics, Chemistry and Materials Science"

CURRENT APPLIED PHYSICS "Physics, Chemistry and Materials Science" AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 1567-1739 DESCRIPTION . Current Applied Physics (Curr. Appl. Phys.) is a monthly published international interdisciplinary journal covering all applied science in physics, chemistry, and materials science, with their fundamental and engineering aspects. Topics covered in the journal are diverse and reflect the most current applied research, including: • Spintronics and superconductivity • Photonics, optoelectronics, and spectroscopy • Semiconductor device physics • Physics and applications of nanoscale materials • Plasma physics and technology • Advanced materials physics and engineering • Dielectrics, functional oxides, and multiferroics • Organic electronics and photonics • Energy-related materials and devices • Advanced optics and optical engineering • Biophysics and bioengineering, including soft matters and fluids • Emerging, interdisciplinary and others related to applied physics • Regular research papers, letters and review articles with contents meeting the scope of the journal will be considered for publication after peer review. The journal is owned by the Korean Physical Society (http://www.kps.or.kr ) AUDIENCE . Chemists, physicists, materials scientists and engineers with an interest in advanced materials for future applications. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 2.480 © Clarivate Analytics -

K O R E a N C in E M a 2 0

KOREAN CINEMA 2006 www.kofic.or.kr/english Korean Cinema 2006 Contents FOREWORD 04 KOREAN FILMS IN 2006 AND 2007 05 Acknowledgements KOREAN FILM COUNCIL 12 PUBLISHER FEATURE FILMS AN Cheong-sook Fiction 22 Chairperson Korean Film Council Documentary 294 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 130-010 Animation 336 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Daniel D. H. PARK Director of International Promotion SHORT FILMS Fiction 344 EDITORS Documentary 431 JUNG Hyun-chang, YANG You-jeong Animation 436 COLLABORATORS Darcy Paquet, Earl Jackson, KANG Byung-woon FILMS IN PRODUCTION CONTRIBUTING WRITER Fiction 470 LEE Jong-do Film image, stills and part of film information are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, and Film Festivals in Korea including JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), PIFF APPENDIX (Pusan International Film Festival), SIFF (Seoul Independent Film Festival), Women’s Film Festival Statistics 494 in Seoul, Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival, Seoul International Youth Film Festival, Index of 2006 films 502 Asiana International Short Film Festival, and Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul. KOFIC appreciates their help and cooperation. Contacts 517 © Korean Film Council 2006 Foreword For the Korean film industry, the year 2006 began with LEE Joon-ik's <King and the Clown> - The Korean Film Council is striving to secure the continuous growth of Korean cinema and to released at the end of 2005 - and expanded with BONG Joon-ho's <The Host> in July. First, <King provide steadfast support to Korean filmmakers. This year, new projects of note include new and the Clown> broke the all-time box office record set by <Taegukgi> in 2004, attracting a record international support programs such as the ‘Filmmakers Development Lab’ and the ‘Business R&D breaking 12 million viewers at the box office over a three month run. -

Frequent Occurrence of SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Among Non-Close Contacts Exposed to COVID-19 Patients

J Korean Med Sci. 2021 Aug 23;36(33):e233 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e233 eISSN 1598-6357·pISSN 1011-8934 Brief Communication Frequent Occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 Infectious Diseases, Microbiology & Parasitology Transmission among Non-close Contacts Exposed to COVID-19 Patients Jiwon Jung ,1,2* Jungmin Lee ,3* Eunju Kim ,2 Songhee Namgung ,2 Younjin Kim ,2 Mina Yun ,2 Young-Ju Lim ,2 Eun Ok Kim ,2 Seongman Bae ,1 Mi-Na Kim ,4 Sun-Mi Lee ,3 Man-Seong Park ,3 and Sung-Han Kim 1,2 1Department of Infectious Diseases, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 2Office for Infection Control, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea 3Department of Microbiology, Institute for Viral Diseases, Biosafety Center, College of Medicine, Korea University, Seoul, Korea Received: Jul 8, 2021 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Accepted: Aug 5, 2021 Korea Address for Correspondence: Sung-Han Kim, MD Department of Infectious Diseases, Asan ABSTRACT Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, Songpa-gu, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission among Seoul 05505, Korea. non-close contacts is not infrequent. We evaluated the proportion and circumstances of E-mail: [email protected] individuals to whom SARS-CoV-2 was transmitted without close contact with the index Man-Seong Park, PhD patient in a nosocomial outbreak in a tertiary care hospital in Korea. From March 2020 to Department of Microbiology and Institute March 2021, there were 36 secondary cases from 14 SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Min-Hee Ryu, M.D., Ph.D. Professor Department of Oncology Asan Medical Center University of Ulsan College of Medicine Seoul, Korea Address (Work) Department of Oncology Asan Medical Center 88, Olympic-ro, 43-gil, Songpa-gu Seoul 05505 Korea Tel: 82-2-3010-5935, 3010-3210 Fax: 82-2-3010-6961 e-mail: [email protected] Education 1987. 3 – 1989. 2 Pre-Medicine College of Natural Sciences Seoul National University Seoul, Korea 1989. 3 – 1994. 2 M.D. College of Medicine Seoul National University Seoul, Korea 1996. 3 – 1998. 2 Master of Science Postgraduate School Seoul National University Seoul, Korea 2002. 3 – 2006. 2 Ph.D. Postgraduate School University of Ulsan College of Medicine Seoul, Korea Graduate Training 1994. 3 – 1995. 2 Internship Seoul National University Hospital Seoul, Korea 1995. 3 – 1999. 2 Residency, Internal Medicine Seoul National University Hospital Seoul, Korea 2002. 5 – 2004. 2 Fellowship, Hematology/Oncology Asan Medical Center University of Ulsan College of Medicine Seoul, Korea Professional Experience 2004. 3 – 2009. 10 Assistant Professor Department of Oncology Asan Medical Center University of Ulsan College of Medicine Seoul, Korea 2009. 10 – 2015 .09 Associate Professor Department of Oncology Asan Medical Center University of Ulsan College of Medicine Seoul, Korea 2015. 10 – Present Professor Department of Oncology Asan Medical Center University of Ulsan College of Medicine Seoul, Korea 2020. 3 – Present Chief Department of Oncology Asan Medical Center University of UlsanCollege of Medicine Seoul, -

2020 Global Korea Scholarship

2020 Global Korea Scholarship Application Guidelines for Graduate Degrees 2020 정부초청외국인 대학원 장학생 모집 요강 2020. 2. INDEX I. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................... 1 II. TOTAL NUMBER OF EXPECTED GRANTEES : 1,276 Candidates ................................... 1 III. AVAILABLE UNIVERSITIES AND FIELDS OF STUDY ................................................... 5 IV. ELIGIBILITY .............................................................................................................................. 6 V. REQUIRED DOCUMENTS ...................................................................................................... 10 VI. SELECTION PROCEDURES ................................................................................................. 13 VII. SCHOLARSHIP INFORMATION ........................................................................................ 17 VIII. PERIOD OF SCHOLARSHIP .............................................................................................. 18 IX. KOREAN LANGUAGE PROGRAM ..................................................................................... 19 X. OTHER IMPORTANT NOTES ................................................................................................ 20 XI. CONTACT INFORMATION .................................................................................................. 21 2020 GLOBAL KOREA SCHOLARSHIP Application Checklist ........................................... 23 FORM -

UNIVERSITY of ULSAN(UOU) at a GLANCE What Is UIBP

Do you know SOUTH KOREA ? UNIVERSITY OF ULSAN(UOU) AT A GLANCE APPLY FOR UIBP ? Seoul GDP USD 1.4 trillion (11th in the world) Incheon Establishment Year 1970 ELIGIBILITY REQUIRED DOCUMENTS FOR ADMISSION Daejeon Daegu Kyungju Founder Ju-yung CHUNG (Founder of HYUNDAI Group) GDP per Capita USD 28,000 (28th in the world) Category Details Documents Details Ulsan Gwangju Busan Governance Hyundai Heavy Industries(HHI) Trade USD 1 trillion (8th in the world) Forms downloadable from UOU a) Anyone with foreign citizenship whose parents Application Form Honorary Chancellor Mong-joon CHUNG (Major Shareholder of HHI) global homepage Population 51 million (26th in the world) both also have foreign citizenship, or * http://global.ulsan.ac.kr > Admissions Major Industries Electronic and Electrical, Automotive, Shipbuilding, Chancellor Chung Kil CHUNG (Former Presidential Chief of Staff, Korea) * Applicants(including parents) with dual-citizenship of Statement of Purpose > Overview > Forms & Downloads Korea are not eligible Mechanical, Petrochemical, Steel, Retail, etc. President Yeon Cheon OH (Former President of Seoul National University) Nationality Requirement * Taiwanese applicants are eligible even if one of their Graduation Certificate of MNCs Samsung, LG, Hyundai, SK, POSCO, Lotte, Hanwha, etc. Official Ranking parents holds Korean citizenship Secondary Education, or - 90th in the World (2015 THE 100 under 50 Rankings) b) Anyone with foreign citizenship who completed both Certificate of Equivalent Course - 11th in Korea, 85th in Asia (2015 THE -

Sustainable Development and Intangible Cultural Heritage: a Youthful New Cohort in the Republic of Korea

Sustainable development and intangible cultural heritage: a youthful new cohort in the Republic of Korea Capacity-Building Workshop on ICH Safeguarding Plan for Sustainable Development, Jeonju, July 1 to 5, 2019 Perhaps the next generation of ICH enthusiasts in the Republic of Korea, this group of primary schoolchildren looked around them wide-eyed at the exhibits in the Gijisi Juldarigi museum for the tugging ritual near Dangjin city. Our workshop participants visited this unique museum during the field visit day of the training workshop. Overview Like the hero in the classical novel, 'The Tale of Yu Chungyol', who must undergo a series of tribulations and tests before his meritorious deeds are recognised and rewarded, so it seems is also the fate of ICH when it comes to sustainable development. The great tales of Korea's Joseon dynasty era are set in sweeping landscapes and encompass the range of human frailties and foibles, and our efforts are set in no less extensive a landscape, nor are they less beset by questions and interpretations both difficult and promising. The two subjects - ICH and sustainable development - were brought together firmly when the operational directives of the Unesco 2003 ICH Convention were expanded with the addition of chapter six (adopted by the Convention's General Assembly at its sixth session during May-June 1 2016). In the little over three years since, there has in the field been scant activity to connect ICH with sustainable development - or to place ICH more firmly in the set of core materials that development must employ in order to qualify as being sustainable. -

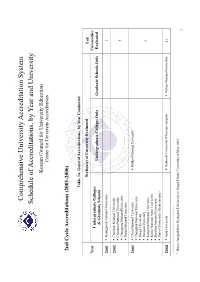

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

RHEE Joo Yull

RHEE Joo Yull Professor Department of Physics Office 32310B, Science Building 2, Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU) Natural Sciences Campus, 2066 Seobu-ro, Jangan-gu, Suwon, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea Phone 82-31-299-4540 Website E-mail [email protected] Social Media Key Words Electronic Structures, Magnetic materials, Optical Properties, Metamaterials, Research Area Condensed-matter physics, Metamaterials Education 1992 PhD Iowa State University, USA 1980 MSc KAIST, Korea 1978 BSc Seoul National University,Korea Experience Sep. 2005 - Now Professor, Sungkyunkwan University Mar. 1994 - Aug.2005 Professor, Hoseo University Aug.1992 -Feb.1994 Post-doctoralFellow, AmesLab, USA Mar. 1980 - Aug. 1985 Assistant Professor, University of Ulsan, Korea Jan. 2009 – Dec. 2010 Editor-in-Chief, Journal of the Korean Physical Society, and Vice President of the Korean Physical Society, Korea Sep. 2011 – Dec. 2012 Editor-in-Chief and Vice President of the Korean Vacuum Society, Korea Position Sep. 2009 - Now Chairman of Dept. of Phys., SKKU Jan. 2010 - Now Editor, Chines Physics B Sep. 2014 - Now Chair, Publication Committee, NanoKorea2015 and NanoKorea2016 Selected Generalized susceptibility and magnetic ordering in rare-earth nickel boride carbides.Phys. Rev. B Publication 51, 15 585 (1995). Realization of room-temperature ferromagnetism and of improved carrier mobility in Mn-doped ZnO film by oxygen deficiency, introduced by hydrogen and heat treatments,Adv. Mater. 19, 3496– 3500 (2007). Realization of a large magnetic moment in the ferromagnetic CoPt bulk phase,Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 067208 (2001) One-dimensional magnetic grating structure made easy,Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 151111 (2006) Active manipulation of plasmonic electromagnetically-induced transparency based on magnetic plasmon resonance, Opt. -

Copyright by Min Jung Son 2004

Copyright by Min Jung Son 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Min Jung Son certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Politics of the Traditional Korean Popular Song Style T’ŭrot’ŭ Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Gerard Béhague Martha Menchaca Avron Boretz Elizabeth Crist The Politics of the Traditional Korean Popular Song Style T’ŭrot’ŭ by Min Jung Son, B.M., M.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctoral of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2004 Dedication To my husband Yn Bok Lee with gratitude and love Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the extraordinary guidance of my dissertation committee. My deepest gratitude and sincere admiration must go to professor Stephen Slawek whose scholarship, insight, and advice have enhanced this project. I am indebted to professor Gerard Béhague for his invaluable advice and theoretical suggestions of the project. Special thanks are also due to professors Martha Menchaca, for her gracious, wise, and patient counsel; Avron Boretz, for his enthusiasm, expertise, and willingness to share his knowledge of East Asian popular culture; Elizabeth Crist, for her attention to detail and musicological abilities that continue to inspire my respect. I acknowledge the assistance and support of many informants of my fieldwork in 2002-2003: t’ŭrot’ŭ singers Kim Sŏn-Jung, Lawrence Cho, Han Song-Hŭi, Lee Su-Jin, Chŏng Hye-Ryŏn, T’ae Min, Ko Yŏng-Jun, and Sul Woon- Do; songwriters Park Nam-Ch’un, O Min-U, and Pan Wa-Yŏl; sound engineer Coi Dong-Kwon; producers Park Kŏ-Yŏl and Chŏng Chin-Yŏng; fans Kim Kwang-Jin and Kwon Yong-Ae. -

NKU Academic Exchange in Ulsan, South Korea

NKU Academic Exchange in Ulsan, South Korea https://www.cia.gov Spend a semester or academic year studying at The University of Ulsan A brief introduction… Office of Education Abroad (859) 572-6908 NKU Academic Exchanges The Office of Education Abroad offers academic exchanges as a study abroad option for independent and mature NKU students interested in a semester or year-long immersion experience in another country. The information in this packet is meant to provide an overview of the experience available through an academic exchange in Ulsan, South Korea. However, please keep in mind that this information, especially those regarding visa requirements, is subject to change. It is the responsibility of each NKU student participating in an exchange to take the initiative in the pre-departure process with regards to visa application, application to the Exchange University, air travel arrangements, housing arrangements, and pre-approval of courses. Before and after departure for an academic exchange, the Office of Education Abroad will remain a resource and guide for participating exchange students. South Korea South Korea is a country swathed in green and the Koreans are a people passionate about nature. Spread over the national parks, peaks and valleys, and hot springs are numerous cultural relics and temples that serve to remind visitors of Korea’s long history. Still, the country’s dedication to keeping up with contemporary times is evident in cutting- edge technologies and the worldwide success of companies such as Samsung, LG and Hyundai. Korea has two distinct seasons, with a wet, hot, monsoon summer and a very cold winter. -

2021 HEAT Application Guidelines

Higher Education for ASEAN Talents (HEAT): Scholarship Opportunity for ASEAN Faculty Members in the Republic of Korea 2021 HEAT Application Guidelines February 2021 2021 Higher Education for ASEAN Talents (HEAT): Scholarship Opportunity for ASEAN Faculty Members in the Republic of Korea 1 DESCRIPTION The Korean Council for University Education (KCUE) in collaboration with the ASEAN- Korea Cooperation Fund (AKCF) launched the Higher Education for ASEAN Talents (HEAT), a full scholarship opportunity for ASEAN faculty members to support acquisition of a doctoral degree in Republic of Korea with the aim to enhance their expertise and promote people-to-people exchanges between Korea and ASEAN universities. Each year 30 scholarship recipients (the ASEAN faculty members representing their university) from 10 ASEAN Members States will be selected (3 persons per country), and each person will receive a full scholarship for three years. KCUE will cover tuition, living expenses, and other costs. Participants will receive a Doctoral degree from a Korean university after completion of the program. HEAT is funded from ASEAN-Korea Cooperation Fund (AKCF), and Korean Council for University Education (KCUE) is the implementing agency of the HEAT project. KCUE is a non-profit, non-governmental association of 4-year universities, representing the voice of member universities to increase autonomy and promote mutual cooperation between universities for the effective development of higher education in Korea. 2 NUMBER OF EXPECTED GRANTEES 2021-2 & 2022-1 :