Art Deco Napier, I Have Focused on Three Principal Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adam David Morton: Spatial Political Economy

SPATIAL POLITICAL ECONOMY Adam David Morton In 2000, it was David Harvey in an interview who commented with some lamentation that although The Limits to Capital ‘was a text that could be built on’ it was, sadly in his view, not taken up in that spirit (see Harvey, 1982; Harvey, 2000: 84). The tangible melancholy in this comment seems somewhat incredulous in the years before and since, given the rightly justified centrality of David Harvey’s agenda-setting work in advancing historical-geographical materialism. For many, Harvey delivers the ‘hard excavatory work’ in providing three cuts to understanding 1) the origin of crises embedded in production; 2) the financial and monetary aspects of the credit system and crisis; and 3) a theory of the geography of uneven development and crises in capitalism. The result, in and beyond The Limits to Capital, is a reading of Marx that offers a spatio-temporal lens on uneven geographical development. Put differently, a combined focus on space and time together reveals the spatiality of power and the command over space as a force in shaping capitalism and the conditions of class struggle. Closer to what is now home, it was Frank Stilwell in Understanding Cities & Regions who crafted the term spatial political economy as a way of approaching the concerns of political economy in relation to cities and regions, space and place (Stilwell, 1992). The exhortation here was to give political economy a spatial twist: to develop a spatial political economy able to grapple with the relationship between social processes and spatial form. Moreover, the approach of spatial political economy aims to do so in such a way that would have both a spatial and temporal dimension. -

SL MAGAZINE Winter 2018 State Library of New South Wales NEWS

–Winter 2018 Vanessa Berry goes underground Message Since I last wrote to you, the Library has lost one of its greatest friends and supporters. You can read more about Michael Crouch’s life in this issue. For my part, I salute a friend, a man of many parts, and a philanthropist in the truest sense of the word — a lover of humanity. Together with John B Fairfax, Sam Meers, Rob Thomas, Kim Williams and many others, he has been the enabling force behind the transformation currently underway at the Library. Roll on October, when we can show you what the fuss is about. Our great Library, as it stands today, is the result of nearly 200 years of public and private partnerships. It is one of the NSW Government’s most precious assets, but much of what we do today would be impossible without additional private support. The new galleries in the Mitchell Building are only one example of this. Our Foundation is currently supporting many other projects, including Caroline Baum’s inaugural Readership in Residence, our DX Lab Fellow Thomas Wing-Evans’ ground-breaking work, the Far Out! educational outreach program, the National Biography Award, the Sydney Harbour Bridge online exhibition (currently in preparation), not to mention the preservation and preparation of our oil paintings for the major hang later this year. All successful institutions need to have a clear idea of what they stand for if they are to continue to attract support from both government and private benefactors. At the first ‘Dinner with the State Librarian’ on 12 April, I addressed an audience of more than 100 supporters about the Library in its long-term historical context — stressing the importance of preserving both oral and written traditions in our collections and touching on the history we share with museums. -

AIA REGISTER Jan 2015

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS REGISTER OF SIGNIFICANT ARCHITECTURE IN NSW BY SUBURB Firm Design or Project Architect Circa or Start Date Finish Date major DEM Building [demolished items noted] No Address Suburb LGA Register Decade Date alterations Number [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1910 Caledonia Hotel 110 Aberdare Street Aberdare Cessnock 4702398 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1905 Denman Hotel 143 Cessnock Road Abermain Cessnock 4702399 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1906 St Johns Anglican Church 13 Stoke Street Adaminaby Snowy River 4700508 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adaminaby Bowling Club Snowy Mountains Highway Adaminaby Snowy River 4700509 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1920 Royal Hotel Camplbell Street corner Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701604 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1936 Adelong Hotel (Town Group) 67 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701605 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelonia Theatre (Town Group) 84 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701606 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelong Post Office (Town Group) 80 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701607 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Golden Reef Motel Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701725 PHILIP COX RICHARDSON & TAYLOR PHILIP COX and DON HARRINGTON 1972 Akuna Bay Marina Liberator General San Martin Drive, Ku-ring-gai Akuna Bay Warringah -

The Journal of Professional Historians Issue Seven, 2020 Circa: the Journal of Professional Historians Issue Seven, 2020 Professional Historians Australia

Circa The Journal of Professional Historians Issue seven, 2020 Circa: The Journal of Professional Historians Issue seven, 2020 Professional Historians Australia Editor: Christine Cheater ISSN 1837-784X Editorial Board: Carmel Black Neville Buch Emma Russell Richard Trembath Ian Willis Layout and design: Lexi Ink Design Copy editor: Fiona Poulton Copyright of articles is held by the individual authors. Except for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted by the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the author. Address all correspondence to: The Editor, Circa Professional Historians Australia PO Box 9177 Deakin ACT 2600 [email protected] The content of this journal represents the views of the contributors and not the official view of Professional Historians Australia. Cover images: Top: Ivan Vasiliev in an extract from Spartacus during a gala celebrating the reopening of the Bolshoi Theatre, 28 October 2011. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/13260/photos/10521 Bottom: Hoff’s students Treasure Conlon, Barbara Tribe and Eileen McGrath working on the Eastern Front relief for the Anzac Memorial, Hoff’s studio, 1932. Photograph courtesy McGrath family CONTENTS EDITORIAL . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..III Part one: Explorations Out of the Darkness, into the Light: Recording child sexual abuse narratives HELEN PENROSE, PHA (VIC & TAS) 2 Part two: Discoveries Discoveries to A Women’s Place: Women and the Anzac Memorial DEBORAH BECK, PHA (NSW & ACT). .. 9 Planter Inertia: The decline of the plantation in the Herbert River Valley BIANKA VIDONJA BALANZATEGUI, PHA (QLD). 20 Part three: Reflections DANCE AS PERFORMATIVE PUBLIC HISTORY?: A JOURNEY THROUGH SPARTACUS CHRISTINE DE MATOS, PHA (NSW & ACT) . -

Australia's Martial Madonna: the Army Nurse's Commemoration in Stained

Australia’s Martial Madonna: the army nurse’s commemoration in stained glass windows (1919-1951) Susan Elizabeth Mary Kellett, RN Bachelor of Nursing (Honours), Graduate Diploma of Nursing (Perioperative) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of History and Philosophical Enquiry Abstract This thesis examines the portrayal of the army nurse in commemorative stained glass windows commissioned between 1919 and 1951. In doing so, it contests the prevailing understanding of war memorialisation in Australia by examining the agency of Australia’s churches and their members – whether clergy or parishioner – in the years following World Wars I and II. Iconography privileging the nurse was omitted from most civic war memorials following World War I when many communities used the idealised form of an infantryman to assuage their collective grief and recognise the service of returned menfolk to King and Country. Australia’s religious spaces were also deployed as commemorative spaces and the site of the nurse’s remembrance as the more democratic processes of parishes and dioceses that lost a member of the nursing services gave sanctuary to her memory, alongside a range of other service personnel, in their windows. The nurse’s depiction in stained glass was influenced by architectural relationships and socio- political dynamics occurring in the period following World War I. This thesis argues that her portrayal was also nuanced by those who created these lights. Politically, whether patron or artist, those personally involved in the prosecution of war generally facilitated equality in remembrance while citizens who had not frequently exploited memory for individual or financial gain. -

Sculptor George Rayner Hoff at War

SCULPTOR GEORGE RAYNER HOFF AT WAR Brad Manera Senior Curator and Historian Anzac Memorial Hyde Park, Sydney At the heart of the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park, his mother, Elizabeth Amy Hoff, of Cloister Coage, There was lile aempt to harness the specialised Sydney, is the sculpture Sacrifice. The arst who Nongham, as his next of kin. On inial examinaon talents that individuals were bringing to the ranks of created it, George Rayner Hoff, was a poet and a his height was recorded at 5’ 6¾” and chest this volunteer army drawn democracally from across storyteller in bronze and stone. His works have measurement of 36” when fully expanded. Hoff was Britain and inspired by patriosm and duty. extraordinary power. graded ‘A1’ and the inspecng medical officer even Training consisted of a noted that he had a small scar on the back of his right Those who know me are well aware that I am no arst, basic introducon to the hand and ‘good teeth’. On 8 December 1915 Private so my untutored opinions on the quality of Hoff’s work life of a soldier that taught George Rayner Hoff was accepted into the Brish Army have no place here. However as a military historian I a man how to lace his Reserve. And given the registraon number 383. would like to understand this remarkable talent and ask heavy, ankle‐length, what we know of his experience in the First World War. As casuales mounted and the training camps sent leather and hob nail their graduates off to the war, Hoff was called to ‘ammunion’ boots, wind Anzac Memorial visitors frequently ask for informaon report for full‐me service. -

Our Triassic Journalists

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 4, Issue 2, February 2017, PP 38 -45 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.22259/ijrhss.0402005 Our Triassic Journalists Donald Richardson University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia (retired) ABSTRACT In 2000, the Australian Government amended the Copyright Act 1968 by passing the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights). This was necessitated by disputes among producers, directors and writers of cinematographic films as to which should be accredited as 'author' of the material for copyright purposes. The Amendment provided 'moral rights' to authors of many kinds of creative works, but the formulation contained within itself the means of its own denaturation. The current research indicates that this has never been remarked upon by the Australian community with the result that the principle of the Amendment is infringed with impunity in the press very frequently. Efforts to have this deficiency rectified have been unsuccessful so far. Keywords: art, design, craftsmanship, moral rights, authorship, attribution, functionality When the Adelaide press announced in mid-1919 that a memorial would be erected in the city to the late king Edward VII the city was assured that it would be made 'by one of the best men in the Empire' – but the artist was not named. Neither was he named in a meticulously detailed report of 19 June 1920, which told that the sculpture had arrived in Adelaide from London – 'in 114 packing cases' – and that the pedestal, which was being made locally, was nearing completion. However, that report did name all the local people who had worked on the pedestal's erection: the builder, the mason who cut the stone steps, the city's Supervisor of Public Buildings and the City Engineer. -

Submissions, It Handed Down Its Report in January, 1988

OUR TRIASSIC JOURNALISTS (Submitted for G C O'Donnell essay prize 2014) Donald Richardson 2014 When the Adelaide press announced in mid-1919 that a memorial would be erected in the city to the late king, Edward VII, the city was assured that it would be made 'by one of the best men in the Empire' – but the artist was not named. Neither was he named in a meticulously detailed report of 19 June, 1920, which told that the sculpture had arrived in Adelaide from London – 'in 114 packing cases' – and that the pedestal, which was being made locally, was nearing completion. However, that report did name all the local people who had worked on the pedestal's erection: the builder (Walter Torode), the mason who cut the stone steps (W H Martin), the city's Supervisor of Public Buildings (A E Simpson) and the City Engineer (J R Richardson). The memorial – which has, in recent years, been revealed again in its true glory by the re-designing of its site, North Terrace – was unveiled by the visiting Prince of Wales. But the artist's name was still not mentioned on the invitation to the unveiling! Adelaide had to wait until the 16 July issue of The Advertiser to be informed that the sculptor was none other than Bertram Mackennal, the only Australian artist ever to be elected to the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts (RA) – who, soon after the unveiling, was dubbed our first artist knight by the king (his friend!). Mackennal, who had migrated to London several years before, had made the memorial before the 1914-18 war, but – because bronze had been commandeered for the war effort – casting had to wait until 1919. -

ANZAC Memorial

Nationally Significant 20th-Century Architecture Revised date 20/07/2011 ANZAC Memorial Address Hyde Park, Sydney, NSW, 2000 Practice Charles Bruce Dellit Sculptures by Raynor Hoff Designed 1932 Completed 1934 History & The Returned Services League of Australia planned a major Description memorial to the forces that fought in the Great War. In 1918 & in 1929 they held an architectural competition in which 117 entries were received. Bruce Dellit’s winning entry stated that it was designed around the inspiration of Endurance, Courage & Sacrifice. The Anzac Memorial & the Pool of Reflection to its north form the focal point for Hyde Park South. The Memorial was designed as a sculptural monument being symmetrical on both axes with stepped massing clad in Bathurst granite. It incorporates traditional elements (buttresses, tall windows, high ceilings), but interprets them in an Art Deco style. Grand external staircases lead to the podium level and extend on the north & south sides of the building. The memorial is adorned externally with many sculptures representing the various Australian armed forces & support units, the four large standing figures at the top of each corner of the building representing the Infantry, Navy, Air Force & Army Medical Corps. The Hall of Memory is located in the View from the north centre of the building & is circular in plan. The sculpture (Source: NSW Government Architect’s 'Sacrifice' in the Hall of Silence is visible in a well as if to hold Office) the sculpture in its embrace. The floors at both levels are Ulum white marble. In the Hall of Silence, the marble is inlayed with a bronze flame that flares out from the centrally located sculpture. -

Anzac Rituals – Secular, Sacred, Christian

Anzac Rituals – Secular, Sacred, Christian Department of History School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney Darren Mitchell A thesis submitted in 2020 to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. I certify that, to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Signature: ------------------------------ Name: Darren Mitchell i Abstract This thesis will argue that Australia’s Anzac ceremonial forms emerged from Christian thinking and liturgy. Existing accounts of Anzac Day have focussed on the secular and Western classical forms incorporated into Anzac ritual and ignored or minimised the significant connection between Christianity and Anzac Day. Early Anzac ceremonies conducted during the Great War were based on Anglican forms, and distinctive commemorative components such as laying wreaths at memorials and pausing in silence, as well as the unique Australian ‘dawn service’ tradition which began ten years after war’s end, have their antecedents in religious customs and civic rites of the time. Anglican clergy played the leading role in developing this Anzac legacy - belief in Australia in the 1910s and 1920s remained predominantly Christian, with approximately half of believers being Anglican adherents - yet this influence on Anzac ritual has heretofore received scant acknowledgement in academic and popular commentary which views Anzac Day’s rituals as ‘secular’, devoid of religious tradition and in competition with it. -

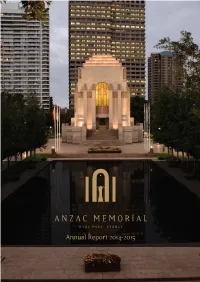

Annual Report 2014-2015 Table of Contents

Annual Report 2014-2015 Table of Contents Letter from the Trustees 2 Report of the Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building 3 Mission Historical Background The Building of the Memorial Description of the Memorial Rededication of the Memorial Access 6 Governance 7 The Trustees Legislative Charter Who are the Trustees? Meetings Achievements 8 Building Management and Maintenance Anzac Memorial Centenary Project This Year in Numbers Public Program Highlights Events and Commemoration Services Staffing 13 Guardians of the Anzac Memorial Anzac Memorial Staff 2014-15 Staff Training EEO Requirements Exemption Organisational Chart Anzac Memorial Staff - 2011-15 General Disclosures 15 Overseas Travel Publications and Lectures Accounts Payable Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 Multicultural Policies and Services Program Consultants Insurances Work Health Safety Risk Management Waste Internal Audit and Risk Management Policy Attestation Heritage Management Consumer Response Audit Report 19 Financial Statements 21 [ 1 ] Report of the Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building for the Year Ended 30 June 2015 This is the thirty-first report of the Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building since enactment of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act and covers the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015. The Trustees’ Mission for the Memorial is: 1. To maintain and conserve the Anzac Memorial as the principal State War Memorial in New South Wales. 2. To preserve the memory of those who have served our country in war by: - collecting, preserving, displaying and researching military historical material and information relating to New South Wales citizens who served their country in war or in peace-keeping activities - educating members of the public in the history of the Memorial and Australian military service through tours and displays. -

University House Formerly N.E.S.C.A House King Street Newcastle

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOLUME 1 OF 3 UNIVERSITY HOUSE FORMERLY N.E.S.C.A HOUSE KING STREET NEWCASTLE Prepared for: Prepared by EJE Heritage APRIL 2011 Ref: 8836-CMP-UH-002 CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN UNIVERSITY HOUSE, NEWCASTLE TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.2 HERITAGE LISTINGS ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 SITE AND OWNERSHIP ..................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES ............................................................................................. 8 1.5 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................... 8 1.6 DEFINITIONS ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. HISTORY OF UNIVERSITY HOUSE...........................................................................................................