Download (223Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

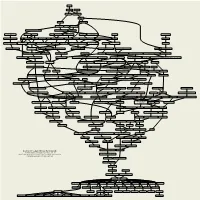

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’S Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ

Blackwell’s Rare Books Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Blackwell’S rare books Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS V Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwell.co.uk/ rarebooks Our premises are in the main Blackwell bookstore at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest, as well as a large secondhand books department. There is lift access to each floor. The bookstore is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and close to several of the colleges and other university buildings, with on street parking close by. Oxford is at the centre of an excellent road and rail network, close to the London - Birmingham (M40) motorway and is served by a frequent train service from London (Paddington). Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Purchases: We are always keen to purchase books, whether single works or in quantity, and will be pleased to make arrangements to view them. Auction commissions: We attend a number of auction sales and will be happy to execute commissions on your behalf. Blackwell online bookshop www.blackwell.co.uk Our extensive online catalogue of new books caters for every speciality, with the latest releases and editor’s recommendations. -

University of Groningen Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Bremmer

University of Groningen Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Bremmer, J.N. Published in: Griechische Mythologie und Frühchristentum IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N. (2005). Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece: Observations on a Difficult Relationship. In R. von Haehling (Ed.), Griechische Mythologie und Frühchristentum (pp. 21-43). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 N. Oettinger, ‘Entstehung von Mythos aus Ritual. Das Beispiel des hethitischen textes CTH 390A’, in M. Hutter and S. Hutter-Braunsar (eds), Offizielle Religion, lokale Kulte und individuelle Religiosität (Münster, 2004) 347-56. MYTH AND RITUAL IN ANCIENT GREECE: OBSERVATIONS ON A DIFFICULT RELATIONSHIP by JAN N. -

Golyzniak Zu Wagner Boardman

Diana SCARISBRICK – Claudia WAGNER – John BOARDMAN, The Beverly Collec- tion of Gems at Alnwick Castle. The Philip Wilson Gems and Jewellery Series Bd. 2. London/New York: Philip Wilson Publishers 2016, 320 S., 480 farb. Abb. Since the 18th century the ancient Percy family, earls of Northumberland has been collecting engraved gems. Their assemblage is presently housed at Alnwick Castle. Traditionally referred as the Beverly Gems,1 now they are published in a fabulous book prepared by the top researchers in the field of glyptics: Diana Sca- risbrick, Claudia Wagner, and Sir John Boardman from the Beazley Archive, Oxford.2 Their new volume is a sizable and richly illustrated book that for sure will be of much interest to archaeologists, art historians, and all people interes- ted in gem engraving and the history of collecting. The book starts with a short preface outlining the basic scope and history of the project embarked on by the Oxford researchers (p. vii). This is followed by a list of the abbreviations that are used in the book, including essential guidance to the catalogue entries (pp. viii-xiii). Next, the history of the collection is pre- sented (pp. xv-xxv). This section, deeply researched and fully referenced to the archival material, is written in an approachable way by Diana Scarisbrick. The conclusion to the first part includes commentary on the records of the Beverly Gems and casts as well as the previous scholarship devoted to them.3 While the merit of earlier works should not be diminished, it is only with the present book authored by the Oxford researchers that we have a thorough study of the who- le collection. -

Diodoros of Sicily

STUDIA HELLENISTICA 58 DIODOROS OF SICILY HISTORIOGRAPHICAL THEORY AND PRACTICE IN THE BIBLIOTHEKE edited by Lisa Irene HAU, Alexander MEEUS, and Brian SHERIDAN PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - BRISTOL, CT 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................. IX SETTING THE SCENE Introduction ......................................... 3 Lisa Irene HAU, Alexander MEEUS & Brian SHERIDAN New and Old Approaches to Diodoros: Can They Be Reconciled? 13 Catherine RUBINCAM DIODOROS IN THE FIRST CENTURY Diodoros of Sicily and the Hellenistic Mind ................ 43 Kenneth S. SACKS The Origins of Rome in the Bibliotheke of Diodoros .......... 65 Aude COHEN-SKALLI In Praise of Pompeius: Re-reading the Bibliotheke Historike..... 91 Richard WESTALL GENRE AND PURPOSE From Ἱστορίαι to Βιβλιοθήκη and Ἱστορικὰ Ὑπομνήματα . 131 Johannes ENGELS History’s Aims and Audience in the Proem to Diodoros’ Bibliotheke 149 Alexander MEEUS A Monograph on Alexander the Great within a Universal History: Diodoros Book XVII ................................... 175 Luisa PRANDI VI TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW QUELLENFORSCHUNG Errors and Doublets: Reconstructing Ephoros and Appreciating Diodoros ........................................... 189 Victor PARKER A Question of Sources: Diodoros and Herodotos on the River Nile ............................................... 207 Jessica PRIESTLEY Diodoros’ Narrative of the First Sicilian Slave Revolt (c. 140/35- 132 B.C.) – a Reflection of Poseidonios’ Ideas and Style? ....... 221 Piotr WOZNICZKA How to Read a Diodoros Fragment ....................... 247 Liv Mariah YARROW COMPOSITION AND NARRATIVE Narrator and Narratorial Persona in Diodoros’ Bibliotheke (and their Implications for the Tradition of Greek Historiography)... 277 Lisa Irene HAU Ring Composition in Diodoros of Sicily’s Account of the Lamian War (XVIII 8–18) ..................................... 303 John WALSH Terminology of Political Collaboration and Opposition in Dio- doros XI-XX ....................................... -

The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs

The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs: Foundational Texts Compared Edited by Fritz-Heiner Mutschler The Homeric Epics and the Chinese Book of Songs: Foundational Texts Compared Edited by Fritz-Heiner Mutschler This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Fritz-Heiner Mutschler and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0400-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0400-4 Contents Acknowledgments vii Conventions and Abbreviations ix Notes on Contributors xi Introduction 1 PART I. THE HISTORY OF THE TEXTS AND OF THEIR RECEPTION A. Coming into Being 1. The Formation of the Homeric Epics 15 Margalit FINKELBERG 2. The Formation of the Classic of Poetry 39 Martin KERN 3. Comparing the Comings into Being of Homeric Epic and the Shijing 73 Alexander BEECROFT B. “Philological” Reception 1. Homeric Scholarship in its Formative Stages 87 Barbara GRAZIOSI 2. Odes Scholarship in its Formative Stage 117 Achim MITTAG 3. The Beginning of Scholarship in Homeric Epic and the Odes: a Comparison 149 GAO Fengfeng / LIU Chun C. Cultural Role 1. Homer in Greek Culture from the Archaic to the Hellenistic Period 163 Glenn W. -

Biblioteks Historie 7

DANSK BIBLIOTEKSHISTORISK SELSKAB BIBLIOTEKS HISTORIE 7 KØBENHAVN 2005 Bibliotekshistorie 7 Udgivet af Dansk Bibliotekshistorisk Selskab Redaktion: Steen Bille Larsen under medvirken af Ole Harbo Jørgen Svane-Mikkelsen © Dansk Bibliotekshistorisk Selskab 2005 ISSN 0109-923X Sats og tryk Handy-Print A/S, Skive Indhold Universitetsbiblioteket i Göttingen, oplysningstidens mønsterbibliotek En beskrivelse af dets udvikling i pionertiden Af Sigrid Schacht 5 Bibliotekstilbud i København før de kommunale folkebiblioteker Lejebiblioteker, klub- og foreningsbiblioteker samt folkebiblioteker ca. 1850-1885 Af Kirsten Mosolff 25 "Bibliotekssagen trænger til Organisation" Folkebibliotekerne i Danmark 1880-1920 Af Laura Skouvig 73 Tre efterreformatoriske katolske biblioteker i København indtil 1962 Af Helge Clausen 110 "Biblioteket som musikkens skatkammer" Aspekter på et bibliotekarisk uddannelsesforløb Af Bent Christiansen 170 Dansk Bibliotekshistorisk Selskab Styrelsens beretning 2002-2003 199 Universitetsbiblioteket i Göttingen, oplysningstidens mønsterbibliotek En beskrivelse af dets udvikling i pionertiden Af Sigrid Schackt Universitetsinstitutionens grundlæggelse Grundlæggeren af Göttingens Universitet, kong Georg 2. af England, var født kurfyrste af Hannover. Den engelske trone arve- de han efter sin far, der som den første hannoveraner blev britisk re- gent. Personalunionen mellem Hannover og Storbritannien varede fra 1714-1837. Da Georg 2. i 1733 udstedte en forordning om op- rettelse af et universitet i sit tyske kurfyrstendømme, lagde han -

Christian Gottlob Heyne and the Changing Fortunes of the Commentary in the Age of Altertumswissenschaft

Christian Gottlob Heyne and the changing fortunes of the commentary in the age of Altertumswissenschaft Book or Report Section Accepted Version Harloe, K. (2015) Christian Gottlob Heyne and the changing fortunes of the commentary in the age of Altertumswissenschaft. In: Kraus, C. S. and Stray, C. (eds.) Classical Commentaries: Explorations in a scholarly genre. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 435-456. ISBN 9780199688982 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/39805/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Oxford University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Christian Gottlob Heyne and the Changing Fortunes of the Commentary in the Age of Altertumswissenschaft Katherine Harloe This chapter seeks to explore issues raised by the major commentaries on Tibullus, Virgil and the Iliad that came from the pen of Christian Gottlob Heyne (1729–1812). For a long time Heyne was neglected within classical scholars’ understanding of their own history, yet in his own age he was something of a European intellectual celebrity, and even at the end of the nineteenth century Friedrich Paulsen could identify him as ‘indisputably the leader in the field of classical studies in Germany during the second half of the eighteenth century’ (1885: 441). -

Who's Zoomin' Who? Bhagavadgītā Recensions in India and Germany

Bagchee and Adluri International Journal of Dharma Studies (2016) 4:4 DOI 10.1186/s40613-016-0026-8 RESEARCH Open Access Who’s Zoomin’ Who? Bhagavadgītā Recensions in India and Germany Joydeep Bagchee1 and Vishwa Adluri2* * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 2Hunter College, New York, USA Full list of author information is This article discusses the political and theological ends to which the thesis of different available at the end of the article “recensions” of the Bhagavadgītā were put in light of recent work on the search for an “original” Gītā (Adluri, Vishwa and Joydeep Bagchee, 2014, The Nay Science: A History of German Indology; Adluri, Vishwa and Joydeep Bagchee, 2016a, Paradigm Lost: The Application of the Historical-Critical Method to the Bhagavad Gītā). F. Otto Schrader in 1930 argued that the “Kashmir recension” of the Bhagavadgītā represented an older and more authentic tradition of the Gītā than the vulgate text (1930, 8, 10). In reviews of Schrader’s work, Franklin Edgerton (Journal of the American Oriental Society 52: 68–75, 1932) and S. K. Belvalkar (New Indian Antiquary 2: 211–51, 1939a) both thought that the balance of probabilities was rather on the side of the vulgate. In a trenchant critique, Edgerton took up Schrader’s main arguments for the originality of the variant readings or extra verses of the Kashmir version (2.5, 11; 6.7; 1.7; 3.2; 5.21; 18.8; 6.16; 7.18; 11.40, 44; 13.4; 17.23; 18.50, 78) and dismissed them out of hand (1932, 75). Edgerton’s assessment was reinforced by Belvalkar, who included a survey of various other “versions” of the Gītā in existence, either by hearsay or imitation. -

Perspectives on the Musical Essays of Lorenz Christoph

4/0 PERSPECTIVES ON THE MUSICAL ESSAYS OF LORENZ CHRISTOPH MIZLER (1711-1778) THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Sandra Pinegar, B.M., M.M. Denton, Texas August, 1984 Pinegar, Sandra, Perspectives on the Musical Essays of Lorenz Christoph Mizler (1711-1778). Master of Arts (Musicology), August, 1984, 138 pp., 10 examples, bibliography, 84 titles. This study provides commentary on Mizler's Dissertatio and Anfangs- GrUnde des General Basses. Chapter V is an annotated guide to his Neu er6ffnete musikalische Bibliothek, one of the earliest German music periodicals. Translations of Mizler's biography in Mattheson's Grundlage einer Ehrenpforte and selected passages of Mizler's Der musikalischer Staarstecher contribute a sampling of the critical polemics among Mizler, Mattheson, and Scheibe. As a proponent of the Aufklhrung, Mizler was influenced by Leibnitz, Thomasius, and Wolff. Though his attempts to apply mechanistic principles to music were rejected during his time, his founding of a society of musical sciences, which included J. S. Bach, Telemann, Handel, and C. H. Graun as members, and his efforts to estab- lish music as a scholarly discipline deserve recognition. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF EXAMPLES ........... .... ....... .......... iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION........ ... ..... ...... .... 1 II. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION.......................... 8 Including a Translation of Mizier's Biography in Johann Mattheson's Grundlage einer Ehrenpforte III. MIZLER'S DISSERTATIO QUOD MUSICA SCIENTIA SIT ET PARS ERUDITIONIS PKILOSOP4ICAE (1734)...... 39 IV. MIZLER'S ANFANGS-GRUNDE DES GENERAL BASSES(1739).. ..... ....... .".". .47 V. AN ANNOTATED GUIDE TO MIZLER'S NEU ERtFFNETE MUSIKALISCHE BIBLIOTHEK (1736-1754) 76 VI. -

Homer in Print: the Transmissions and Reception of Homer’S Works

Homer in Print: The Transmissions and Reception of Homer’s Works Homer before Print Iliad Manuscript on papyrus, Second century CE. Ms. 1063. Edgar J. Goodspeed Papyri Collection. Antonio Maria Ceriani (1828-1907) Ilias Ambrosiana, Cod. F. 205 P. inf., Bibliothecae Ambrosianae Mediolanensi Berna: In aedibus Urs Graf, 1953. BHL E1 Codex Venetus Marcianus (known as Venetus A) Reproduction from Book One of the Iliad, f. 12r. Demetrio Calcondila (1423–1511) ‘H τοῦ ‘Oμήρου ποίησις ἅπασα Florence: Bernardus Nerlius, Nerius Nerlius, and Demetrius Damilas, 1488. BHL A1 Humanists, Scholars, and Students Aldo Manuzio (1449/50–1515) ‘Oμήρου ’Iλιάς, Όδύσσεια. βατραχομυομαχία. ὕμνοι. λβ = Homeri Ilias, Vlyssea. Venice: Aldus, 1504. BHL A2 Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494) ‘Oμήρου Όδυσσείας βίβλοι Α. καὶ Β. = Homeri Vlysseae. Basel: Ex aedibus Andreae Cratandri, 1520. BHL A4 Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457) Homeri Poetae Clarissimi Ilias per Laurentium Vallensem Romanum Latina Facta Cologne: Apud Heronem Alopecium, 1522 BHL C1 Nikolas Brylinger (fl. 1537–1565) and Sébastien Castellion (1515–1563) Homeri opera graeco-latina, quae quidem nunc extant, omnia. Hoc est: Ilias, Odyssea, Batrachomyomachia, et Hymni. Basel: Per Nicolaum Brylingerum, 1561. BHL A13 Thomas Clark (1787–1860) The Iliad of Homer with an Interlinear Translation, for the Use of Schools and Private Learners, on the Hamiltonian System, as Improved by Thomas Clark Philadelphia: David McKay, Publisher, 1888. Hamilton, Locke and Clark Series. BHL B91 S. H. Butcher (1850–1910) and Andrew Lang (1844–1912) The Odyssey of Homer Done into English Prose London: Macmillan and Co., 1879. BHL B55 A. T. Murray (1866–1940) The Odyssey. London: William Heinemann; New York: G. -

Vergil's Aeneid and Homer Georg Nicolaus Knauer

Vergil's "Aeneid" and Homer Knauer, Georg Nicolaus Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1964; 5, 2; ProQuest pg. 61 Vergil's Aeneid and Homer Georg Nicolaus Knauer FTEN since Vergil's Aeneid was edited by Varius and Plotius O Tucca immediately after the poet's death (18/17 B.C.) and Propertius wrote his (2.34.6Sf) cedite Romani scriptores, cedite Grat, nescio qUid maius nascitur Iliade Make way, ye Roman authors, clear the street, 0 ye Greeks, For a much larger Iliad is in the course of construction (Ezra Pound, 1917) scholars, literary critics and poets have tried to define the relation between the Aeneid and the Iliad and Odyssey. As one knows, the problem was not only the recovery of details and smaller or larger Homeric passages which Vergil had used as the poet ical background of his poem. Men have also tried from the very be ginning, as Propertius proves, to evaluate the literary qualities of the three respective poems: had Vergil merely stolen from Homer and all his other predecessors (unfortunately the furta of Perellius Faustus have not come down to us), is Vergil's opus a mere imitation of his greater forerunner, an imitation in the modern pejorative sense, or has Vergil' s poetic, philosophical, even "theological" strength sur passed Homer's? Was he-not Homer-the maximus poetarum, divinissimus Maro (Cerda)? For a long time Vergil's ars was preferred to Homer's natura, which following Julius Caesar Scaliger one took to be chaotic, a moles rudis et indigesta (Cerda, following Ovid Nlet.