Centro Teaching Guide Frank Bonilla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universiv Micrdmlms International Aoon.Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Ml 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality o f the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. I f copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

2006 Annual Report.NYSCJC

ANNUAL REPORT 2006 NEW YORK STATE COMMISSION ON JUDICIAL CONDUCT NEW YORK STATE COMMISSION ON JUDICIAL CONDUCT * * * COMMISSION MEMBERS RAOUL LIONEL FELDER, ESQ., CHAIR HON. THOMAS A. KLONICK, VICE CHAIR STEPHEN R. COFFEY, ESQ. COLLEEN DIPIRRO RICHARD D. EMERY, ESQ. PAUL B. HARDING, ESQ. MARVIN E. JACOB, ESQ. HON. DANIEL F. LUCIANO HON. KAREN K. PETERS HON. TERRY JANE RUDERMAN * * * CLERK OF THE COMMISSION JEAN M. SAVANYU, ESQ. * * * 61 BROADWAY NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10006 38-40 STATE STREET (PRINCIPAL OFFICE) 400 ANDREWS STREET ALBANY, NEW YORK 12207 ROCHESTER, NEW YORK 14604 WEB SITE: www.scjc.state.ny.us COMMISSION STAFF ROBERT H. TEMBECKJIAN Administrator and Counsel CHIEF ATTORNEYS CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER Cathleen S. Cenci (Albany) Diane B. Eckert Alan W. Friedberg (New York) John J. Postel (Rochester) BUDGET/FINANCE OFFICER Shouchu (Sue) Luo STAFF ATTORNEYS ADMINISTRATIVE PERSONNEL Kathryn J. Blake Lee R. Kiklier Melissa R. DiPalo Shelley E. Laterza Vickie Ma Linda J. Pascarella Jennifer Tsai Wanita Swinton-Gonzalez Stephanie McNinch SENIOR INVESTIGATORS SECRETARIES/RECEPTIONISTS Donald R. Payette Georgia A. Damino David Herr Linda Dumas Lisa Gray Savaria INVESTIGATORS Evaughn Williams Rosalind Becton SENIOR CLERK Margaret Corchado Sara S. Miller Zilberstein Miguel Maisonet Rebecca Roberts Betsy Sampson IT/COMPUTER SPECIALIST Herb Munoz NEW YORK STATE COMMISSION ON JUDICIAL CONDUCT 61 BROADWAY NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10006 212-809-0566 212-809-3664 RAOUL LIONEL FELDER, CHAIR ROBERT H. TEMBECKJIAN TELEPHONE FACSIMILE HON. THOMAS A. KLONICK, VICE CHAIR ADMINISTRATOR & COUNSEL STEPHEN R. COFFEY www.scjc.state.ny.us COLLEEN C. DIPIRRO RICHARD D. EMERY AUL ARDING P B.H MARVIN E. -

Lee Harvey Oswald, Life-History, and the Truth of Crime

Ghosts of the Disciplinary Machine: Lee Harvey Oswald, Life-History, and the Truth of Crime Jonathan Simon* It seems to me important, very important, to the record that we face the fact that this man was not only human but a rather ordinary one in many respects, and who appeared ordinary. If we think that this was a man such as we might never meet, a great aberration from the normal, someone who would stand out in a crowd as unusual, then we don't know this man, we have no means of recognizing such a person again in advance of a crime such as he committed. The important thing, I feel, and the only protection we have is to realize how human he was though he added to it this sudden and great violence beyond- Ruth Paine' I. INTRODUCTION: EARL WARREN'S HAUNTED HOUSE Thirty-four years ago, the President's Commission on the Assas- sination of President Kennedy, popularly known as the Warren Commission, published its famous report. The Commission's most * Professor of Law, University of Miami; Visiting Professor of Law, Yale Law School. I would like to thank the following for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper Anthony Alfieri, Kristin Bumiller, Marianne Constable, Rosemary J. Coombe, Thomas Dumm, John Hart Ely, Patrick Gudridge, Christine Harrington, Austin Sarat, Adam Simon, and especially Mark Weiner for exceptional editorial assistance. All errors of fact or judgment belong to the author. I would also like to thank the University of Miami School of Law for providing summer research support. -

SONIA SOTOMAYOR, DOCTOR of LAWS Sonia Sotomayor Is The

! 0'(-#!0'/'1#"')7!*',/')!'9!$#@0! ! Sonia Sotomayor is the 111th justice of the United States Supreme Court. She is the first Hispanic and the third of four women to serve the nation’s highest court in its 223-year history. Justice Sotomayor was born to Puerto Rican parents who moved to New York during World War II. Together with her younger brother, she grew up in housing projects in the Bronx and often visited family in Puerto Rico, with whom she maintains close ties. Her father spoke only Spanish, and she did not reach fluency in English until after his death when she was nine. Justice Sotomayor was profoundly influenced by her mother, who instilled in her the value of education and inspired her to declare, at age ten, her interest in attending college and becoming an attorney. She was an avid reader with a love of learning. Diagnosed with Type I diabetes at the age of eight, Justice Sotomayor excelled in school despite the challenges of managing her health. She was valedictorian of her Cardinal Spellman High School class and earned a full scholarship to Princeton University, where she graduated summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa in 1976. At Princeton, she pushed the administration to diversify by introducing classes about Latin America and by hiring Latino faculty. At Yale Law School, Justice Sotomayor was an editor of the Yale Law Journal and managing editor of Yale Studies in World Public Order. After graduating in 1979, she worked in the trial division for Robert Morgenthau, the New York County District Attorney, serving as Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan. -

Table of Contents

Philanthropy, Associations and Advocacy Table of Contents Part I. Latinos and the Development of Community: Philanthropy, Associations and Advocacy by Eugene D. Miller Introduction to Latinos and Philanthropy: Goals and Objectives 1 Week 1. Identity, Diversity, and Growth 5 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Week 2. Patterns ofSettlement 9 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Background Readings on Immigration Week 3. The Eagle and the Serpent: U.S.-Latin American Relations 15 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Film Week 4. Mexican Americans: From the Treaty of Guadalupe de Hidalgo to the League of United Latin American Citizens 21 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings 11 Latinos and the Development ofCommunity Week 5. Mexican Americans: From World War II to Cesar Chavez and the Farm Workers 25 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Films Week 6. Puerto Ricans in New York 31 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Week 7. Cuban Americans: From Castro to the 11/z Generation 37 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Week 8. Dominican Americans in New York 43 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Week 9. The Church in Latin America: From Identification with the Elites to Liberation Theology 49 Discussion Questions and Undergraduate Research Topics Graduate Research Topics Readings Background Readings Philanthropy, Associations and Advocacy 111 Week 10. -

Rationale for a Culturally Based Program of Actionagainst Foverty Among New York Puertoricans

REPOR TRESUMES ED 011 543 UD 0D3 495 RATIONALE FOR A CULTURALLY BASED PROGRAM OF ACTIONAGAINST FOVERTY AMONG NEW YORK PUERTORICANS. BY- BONILLA, FRANK PUB DATE OCT 64 ECRS PRICE MF-$11.09 HC-$0.96 24P. CESCRIPTORS- *PUERTO.RICAN CULTURE, *POVERTY PROGRAMS, *ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED, *FAMILY RELATIONSHIP,CULTURAL FACTORS, CULTURAL BACKGROUND, SEX DIFFERENCES,LANGUAGE PATTERNS, BILINGUALISM, RACIAL CHARACTERISTICS,RACE RELATIONS, RACIAL ATTITUDES, MUSIC ACTIVITIES, MIGRANT FROELEMS, COMMUNITY PROBLMS, NEW YORK CITY THE WRITER TOOK THE POSITION THAT ANY ACTION PROGRAM TO CHANGE THE FOVERTY CONDITIONS OF NEW YORK CITYPUERTO RICANS SHOULD BE BASED ON KNOWLEDGE OF THEIR CULTURALLIFE. THERE' EXISTS AMONG PUERTO RICANS A SENSE OF ETHNICMENTIFICATION AND UNITY WHICH AFFECTS THEIR BEHAVIOR WITHIN THELARGER COMMUNITY. ONE FACTOR WHICH FIGURES IMPORTANTLY IN NEWYORK CITY PUERTO RICAN CULTURE IS THE PROBLEM OF CULTURAL DUALITIES, WHICH ARE A RESULT OF THE STRESS OF ADAPTATION FROM THE ISLAND TO THE MAINLAND CULTURE. FOR EXAMPLE, ALTHOUGH THE FAMILY RELATIONSHIP STILL IS A STRONGLY EXTENDED NETWORK OF KINSHIP WHICH OFFERS A SENSE OF MUTUALOBLIGATION, THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE SEXES HAS BECOMEMORE EQUALITARIAN, AND CONFLICT' HAS ARISEN BETWEEN THEELDER'S CULTURALLY ROOTED BELIEF IN HIS OWN SELF-WORTH, DESPITE HIS REALISTIC AWARENESS OF HIS DISADVANTAGED POSITION, ANC THE ADOLESCENT'S FEELING OF POWER IN THE FAMILY BECAUSE OF HIS BETTER EDUCATION. AN ADDITIONAL IMPORTANT FACTOR IN THE PUERTO RICAN'S BEHAVIOR, ESPECIALLY IN HIS FEELINGS ABOUT DISCRIMINATION, IS HIS COMPLEX RACIAL ATTITUDE. IF PUERTO RICANS CAN BE MADE TO FEEL THAT THEIR CULTURE IS RECOGNIZED ANC AFFIRMED, THEY WILL BE ABLE TO PROVIDE THE IMPORTANT LEADERSHIP TO BRING ABOUT THE NECESSARY CHANGES TO REMOVE THE EFFECTS OF POVERTY IN THEIR COMMUNITY. -

United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

UNITED STATES SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY QUESTIONNAIRE FOR JUDICIAL NOMINEES PUBLIC 1. Name: State full name (include any former names used). Sonia Sotomayor. Former names include: Sonia Maria Sotomayor; Sonia Sotomayor de Noonan; Sonia Maria Sotomayor Noonan; Sonia Noonan 2. Position: State the position for which you have been nominated. Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 3. Address: List current office address. If city and state of residence differs from your place of employment, please list the city and state where you currently reside. Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse 40 Foley Square New York, NY 10007 4. Birthplace: State date and place of birth. June 25, 1954 New York, NY 5. Education: List in reverse chronological order each college, law school, or any other institution of higher education attended and indicate for each the dates of attendance, whether a degree was received, and the date each degree was received. Yale Law School, New Haven, CT, September 1976-June 1979. J.D. received June 1979. Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, September 1972-June 1976. B.A., summa cum laude, received June 1976. 6. Employment Record: List in reverse chronological order all governmental agencies, business or professional corporations, companies, firms, or other enterprises, partnerships, institutions, or organizations, non-profit or otherwise, with which you have been affiliated as an officer, director, partner, proprietor, or employee since graduation from college, whether or not you received payment -

2012 Calendar Journal

CALENDAR JOURNAL La Tuna Estudiantina de Cayey and the Hostos Center for the Arts & Culture present A revue of Puerto Rican music. Celebrating Puerto Rican Heritage Month and the 45th Anniversaries of Hostos Comunity College and La Tuna de Cayey Sat, Nov 17, 2012 ▪ 7:30 pm Main Theater - Hostos Community College/CUNY 450 Grand Councourse at 149th St. ▪ The Bronx Admission: $15, $10 - Info & tkts: 718-518-4455 - www.hostos.cuny.edu/culturearts 2, 4, 5, Bx1, Bx19 to Grand Concourse & 149 St. Made possible, in part, with public funds from the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs in cooperation with the New York City Council. COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE WOULD LIKE TO EXTEND ITS SINCEREST GRATITUDE TO THE SPONSORS AND SUPPORTERS OF PUERTO RICAN HERITAGE MONTH 2012 THE NIELSEN CompanY CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Municipal CREDIT UNION 1199 SEIU UNITED Federation OF TEACHERS WOLF POPPER, LLP CON EDISON Hostos COMMUNITY COLLEGE, CUNY ACACIA NETWORK INSTITUTE FOR THE Puerto RICAN/Hispanic ELDERLY, INC. Colgate PALMOLIVE EL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS PuertorriQUEÑOS HealthPRO MED LEHMAN COLLEGE, CUNY Puerto RICO CONVENTION BUREAU RAIN, INC. MEMBER AGENCIES INSTITUTE FOR THE Puerto RICAN/Hispanic ELDERLY ASPIRA OF NEW YORK EL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS PuertorriQUEÑOS EL MUSEO DEL BARRIO EL PUENTE EUGENIO MARÍA DE Hostos COMMUNITY COLLEGE/CUNY LA CASA DE LA HERENCIA Cultural PuertorriQUEÑA, INC. LA FUNDACIÓN NACIONAL para LA Cultura POPULAR LatinoJUSTICE: PRLDEF MÚSICA DE CÁMARA National CONGRESS FOR Puerto RICAN RIGHTS – JUSTICE COMMITTEE National INSTITUTE FOR Latino POLICY Puerto RICO FEDERAL Affairs Administration COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE HEADQuarters INSTITUTE FOR THE Puerto RICAN/Hispanic ELDERLY 105 East 22nd st. -

Bosque-Perez, Ramon, Ed. Puerto Ricans and Higher Education Policies. Volume 1

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 362 UD 031 355 AUTHOR Rodriguez, Camille, Ed.; Bosque-Perez, Ramon, Ed. TITLE Puerto Ricans and Higher Education Policies. Volume 1: Issues of Scholarship, Fiscal Policies and Admissions. Higher Education Task Force Discussion Series. INSTITUTION City Univ. of New York, N.Y. Centro de Estudios Puertorriguenos. REPORT NO ISBN-1-878483-52-8 PUB DATE Aug 94 NOTE 80p. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Admission (School); *College Bound Students; College Preparation; College School Cooperation; Educational Finance; *Educational Policy; *Financial Support; *Higher Education; Hispanic Americans; Minority Groups; Policy Formation; *Puerto Ricans; *Scholarship; Standards IDENTIFIERS *City University of New York ABSTRACT This volume explores issues of scholarship, fiscal policies, and admissions in the higher education of Puerto Ricans, with the emphasis on Puerto Ricans on the U.S. mainland and a particular focus on Puerto Rican admissions to the City University of New York. The first paer, "The Centio's Models of Scholarship: Present Challenges to Twenty Years of Academic Empowerment" by Maria Josefa Canino considers the history of the Centro Puertorriqueno of Hunter College of the City University of New York and its mission for scholarship and the formation of policy related to Puerto Ricans. The second paper, "Puerto Ricans and Fiscal Policies in U.S. Higher Education: The Case of the City University of New York" by Camille Rodriguez and Ramon Bosque-Perez illustrates the interplay between finance and policy and the education of Puerto Ricans. "Latinos and the College Preparatory Initiative" by Camille Rodriguez, Judith Stern Torres, Milga Morales-Nadal, and Sandra Del Valle discusses the College Preparatory Initiative (CPI), a program designed by the City University of New York as a way to strengthen the educational experiences of students. -

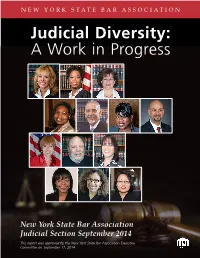

Judicial Diversity: a Work in Progress

NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Judicial Diversity: A Work in Progress New York State Bar Association Judicial Section September 2014 This report was approved by the New York State Bar Association Executive Committee on September 17, 2014 New York State Bar Association Judicial Section JUDICIAL DIVERSITY: A WORK IN PROGRESS This report was approved by the New York State Bar Association Executive Committee on September 17, 2014 New York State Bar Association, Judicial Section Judicial Diversity in New York State: A Work in Progress Table of Contents Introduction page 1 Why Diversity Matters page 1 Executive Summary page 3 Benchmarks of Judicial Diversity in NY State Courts page 11 African Americans page 12 Asian Pacific Americans page 19 Hispanics/Latinos page 26 Lesbians, Gay Men, Bisexuals & Transgender page 35 Native Americans page 38 Women page 40 Law Schools page 45 Recommendations page 46 Conclusion page 47 Appendix page 49 Acknowledgements page 59 Judicial Diversity Committee Back Cover JUDICIAL DIVERSITY IN NEW YORK STATE: A WORK IN PROGRESS INTRODUCTION Diversity matters in commerce, the professions, government, and academia. But nowhere is it more important than in the judiciary, the branch of government charged with safeguarding our country’s constitutional democracy and dispensing justice to its citizenry. It is the ability to petition the courts that keeps people from seeking justice in the streets. If we are to successfully encourage the public to entrust disputes to our courts, we must endeavor to close the confidence gap -

2019 Faculty Distinction

2019 FACULTY DISTINCTION CELEBRATING THE AWARDS, HONORS, AND RECOGNITION OF THE FACULTY OF ARTS & SCIENCES INTRODUCTION he Faculty of Arts & Sciences is the intellectual heart of Columbia University. Our pursuit of fundamental knowledge and understanding spans the arts, Thumanities, natural sciences, and social sciences. The excellence of our faculty is recognized each year with numerous awards and honors. As is tradition, the Executive Committee hosts this event annually to thank the many remarkable faculty who bring such pride and honor to the Arts and Sciences and to Columbia. It is truly extraordinary to read about the scope of your accomplishments, which reinforces our commitment to support and empower the faculty to continue to work at their highest level. Carlos J. Alonso Maya Tolstoy James J. Valentini Dean of the Graduate School Interim Executive Vice Dean of Columbia College of Arts & Sciences President for Arts & Sciences Vice President for Vice President for Graduate Dean of the Faculty of Arts Undergraduate Education Education & Sciences Henry L. and Lucy G. Moses Morris A. and Alma Professor of Earth and Professor Schapiro Professor in the Environmental Sciences Humanities HUMANITIES HUMANITIES Art History and Archaeology Zainab Bahrani Edith Porada Professor of Ancient Near Eastern Art History and Archaeology Andrew Carnegie Fellow Humanities War and Peace Initiative Grant Barry Bergdoll Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History Elected Cattedra Borromini, Accademia di Architettura, Universita de la Svizzera Italiana, Mendrisio, -

Redalyc.Recruiting and Preparing Teachers for New York Puerto

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Mercado, Carmen I. Recruiting and Preparing Teachers for New York Puerto Rican Communities: A Historical Publicy Policy Perspective Centro Journal, vol. XXIV, núm. 2, 2012, pp. 110-139 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37730308006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 110 CENTRO JOURNAL volume xxiv • number ii • fall 2012 Recruiting and Preparing Teachers for New York Puerto Rican Communities: A Historical Publicy Policy Perspective carmen i. mercado abstract In this article I argue that it is time to focus attention on the recruitment and preparation of quality teachers in and for U.S. Puerto Rican communities as a way to address the low-educational attainment and school success of Puerto Rican youth. Although teacher quality is the one factor that has consistently had the largest impact on student success, policies and practices that affect teacher recruitment and preparation are barriers to increasing teacher quality in and for Puerto Rican communities. Nevertheless, advocating for change in the 21st century requires an- ticipating the challenges we face as well as the powerful tools and practices that are needed to overcome these challenges. This article takes a historical, public policy perspective to identify the broad range of resources the Puerto Rican community has developed over six decades of community activism, in the largest Puerto Rican city and Latino city that also prepares the nation’s teachers.