Performance Characterization of the 64-Bit X86 Architecture from Compiler Optimizations’ Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Von Neumann Computer Model 5/30/17, 10:03 PM

The von Neumann Computer Model 5/30/17, 10:03 PM CIS-77 Home http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CIS77syllabus.htm The von Neumann Computer Model 1. The von Neumann Computer Model 2. Components of the Von Neumann Model 3. Communication Between Memory and Processing Unit 4. CPU data-path 5. Memory Operations 6. Understanding the MAR and the MDR 7. Understanding the MAR and the MDR, Cont. 8. ALU, the Processing Unit 9. ALU and the Word Length 10. Control Unit 11. Control Unit, Cont. 12. Input/Output 13. Input/Output Ports 14. Input/Output Address Space 15. Console Input/Output in Protected Memory Mode 16. Instruction Processing 17. Instruction Components 18. Why Learn Intel x86 ISA ? 19. Design of the x86 CPU Instruction Set 20. CPU Instruction Set 21. History of IBM PC 22. Early x86 Processor Family 23. 8086 and 8088 CPU 24. 80186 CPU 25. 80286 CPU 26. 80386 CPU 27. 80386 CPU, Cont. 28. 80486 CPU 29. Pentium (Intel 80586) 30. Pentium Pro 31. Pentium II 32. Itanium processor 1. The von Neumann Computer Model Von Neumann computer systems contain three main building blocks: The following block diagram shows major relationship between CPU components: the central processing unit (CPU), memory, and input/output devices (I/O). These three components are connected together using the system bus. The most prominent items within the CPU are the registers: they can be manipulated directly by a computer program. http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CPU/VonNeumann/lecture.html Page 1 of 15 IPR2017-01532 FanDuel, et al. -

Lecture Notes

Lecture #4-5: Computer Hardware (Overview and CPUs) CS106E Spring 2018, Young In these lectures, we begin our three-lecture exploration of Computer Hardware. We start by looking at the different types of computer components and how they interact during basic computer operations. Next, we focus specifically on the CPU (Central Processing Unit). We take a look at the Machine Language of the CPU and discover it’s really quite primitive. We explore how Compilers and Interpreters allow us to go from the High-Level Languages we are used to programming to the Low-Level machine language actually used by the CPU. Most modern CPUs are multicore. We take a look at when multicore provides big advantages and when it doesn’t. We also take a short look at Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) and what they might be used for. We end by taking a look at Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) and Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC). Stanford President John Hennessy won the Turing Award (Computer Science’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize) for his work on RISC computing. Hardware and Software: Hardware refers to the physical components of a computer. Software refers to the programs or instructions that run on the physical computer. - We can entirely change the software on a computer, without changing the hardware and it will transform how the computer works. I can take an Apple MacBook for example, remove the Apple Software and install Microsoft Windows, and I now have a Window’s computer. - In the next two lectures we will focus entirely on Hardware. -

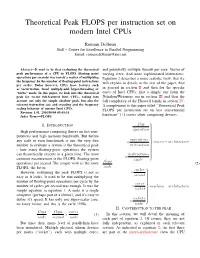

Theoretical Peak FLOPS Per Instruction Set on Modern Intel Cpus

Theoretical Peak FLOPS per instruction set on modern Intel CPUs Romain Dolbeau Bull – Center for Excellence in Parallel Programming Email: [email protected] Abstract—It used to be that evaluating the theoretical and potentially multiple threads per core. Vector of peak performance of a CPU in FLOPS (floating point varying sizes. And more sophisticated instructions. operations per seconds) was merely a matter of multiplying Equation2 describes a more realistic view, that we the frequency by the number of floating-point instructions will explain in details in the rest of the paper, first per cycles. Today however, CPUs have features such as vectorization, fused multiply-add, hyper-threading or in general in sectionII and then for the specific “turbo” mode. In this paper, we look into this theoretical cases of Intel CPUs: first a simple one from the peak for recent full-featured Intel CPUs., taking into Nehalem/Westmere era in section III and then the account not only the simple absolute peak, but also the full complexity of the Haswell family in sectionIV. relevant instruction sets and encoding and the frequency A complement to this paper titled “Theoretical Peak scaling behavior of current Intel CPUs. FLOPS per instruction set on less conventional Revision 1.41, 2016/10/04 08:49:16 Index Terms—FLOPS hardware” [1] covers other computing devices. flop 9 I. INTRODUCTION > operation> High performance computing thrives on fast com- > > putations and high memory bandwidth. But before > operations => any code or even benchmark is run, the very first × micro − architecture instruction number to evaluate a system is the theoretical peak > > - how many floating-point operations the system > can theoretically execute in a given time. -

COSC 6385 Computer Architecture - Multi-Processors (IV) Simultaneous Multi-Threading and Multi-Core Processors Edgar Gabriel Spring 2011

COSC 6385 Computer Architecture - Multi-Processors (IV) Simultaneous multi-threading and multi-core processors Edgar Gabriel Spring 2011 Edgar Gabriel Moore’s Law • Long-term trend on the number of transistor per integrated circuit • Number of transistors double every ~18 month Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wki/Images:Moores_law.svg COSC 6385 – Computer Architecture Edgar Gabriel 1 What do we do with that many transistors? • Optimizing the execution of a single instruction stream through – Pipelining • Overlap the execution of multiple instructions • Example: all RISC architectures; Intel x86 underneath the hood – Out-of-order execution: • Allow instructions to overtake each other in accordance with code dependencies (RAW, WAW, WAR) • Example: all commercial processors (Intel, AMD, IBM, SUN) – Branch prediction and speculative execution: • Reduce the number of stall cycles due to unresolved branches • Example: (nearly) all commercial processors COSC 6385 – Computer Architecture Edgar Gabriel What do we do with that many transistors? (II) – Multi-issue processors: • Allow multiple instructions to start execution per clock cycle • Superscalar (Intel x86, AMD, …) vs. VLIW architectures – VLIW/EPIC architectures: • Allow compilers to indicate independent instructions per issue packet • Example: Intel Itanium series – Vector units: • Allow for the efficient expression and execution of vector operations • Example: SSE, SSE2, SSE3, SSE4 instructions COSC 6385 – Computer Architecture Edgar Gabriel 2 Limitations of optimizing a single instruction -

Reverse Engineering X86 Processor Microcode

Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz, Ruhr-University Bochum https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/koppe This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum Abstract hardware modifications [48]. Dedicated hardware units to counter bugs are imperfect [36, 49] and involve non- Microcode is an abstraction layer on top of the phys- negligible hardware costs [8]. The infamous Pentium fdiv ical components of a CPU and present in most general- bug [62] illustrated a clear economic need for field up- purpose CPUs today. In addition to facilitate complex and dates after deployment in order to turn off defective parts vast instruction sets, it also provides an update mechanism and patch erroneous behavior. Note that the implementa- that allows CPUs to be patched in-place without requiring tion of a modern processor involves millions of lines of any special hardware. While it is well-known that CPUs HDL code [55] and verification of functional correctness are regularly updated with this mechanism, very little is for such processors is still an unsolved problem [4, 29]. known about its inner workings given that microcode and the update mechanism are proprietary and have not been Since the 1970s, x86 processor manufacturers have throughly analyzed yet. -

Assembly Language: IA-X86

Assembly Language for x86 Processors X86 Processor Architecture CS 271 Computer Architecture Purdue University Fort Wayne 1 Outline Basic IA Computer Organization IA-32 Registers Instruction Execution Cycle Basic IA Computer Organization Since the 1940's, the Von Neumann computers contains three key components: Processor, called also the CPU (Central Processing Unit) Memory and Storage Devices I/O Devices Interconnected with one or more buses Data Bus Address Bus data bus Control Bus registers Processor I/O I/O IA: Intel Architecture Memory Device Device (CPU) #1 #2 32-bit (or i386) ALU CU clock control bus address bus Processor The processor consists of Datapath ALU Registers Control unit ALU (Arithmetic logic unit) Performs arithmetic and logic operations Control unit (CU) Generates the control signals required to execute instructions Memory Address Space Address Space is the set of memory locations (bytes) that are addressable Next ... Basic Computer Organization IA-32 Registers Instruction Execution Cycle Registers Registers are high speed memory inside the CPU Eight 32-bit general-purpose registers Six 16-bit segment registers Processor Status Flags (EFLAGS) and Instruction Pointer (EIP) 32-bit General-Purpose Registers EAX EBP EBX ESP ECX ESI EDX EDI 16-bit Segment Registers EFLAGS CS ES SS FS EIP DS GS General-Purpose Registers Used primarily for arithmetic and data movement mov eax 10 ;move constant integer 10 into register eax Specialized uses of Registers eax – Accumulator register Automatically -

State of the Port to X86-64

OpenVMS State of the Port to x86-64 October 6, 2017 1 Executive Summary - Development The Development Plan consists of five strategic work areas for porting the OpenVMS operating system to the x86-64 architecture. • OpenVMS supports nine programming languages, six of which use a DEC-developed proprietary backend code generator on both Alpha and Itanium. A converter is being created to internally connect these compiler frontends to the open source LLVM backend code generator which targets x86-64 as well as many other architectures. LLVM implements the most current compiler technology and associated development tools and it provides a direct path for porting to other architectures in the future. The other three compilers have their own individual pathways to the new architecture. • Operating system components are being modified to conform to the industry standard AMD64 ABI calling conventions. OpenVMS moved away from proprietary conventions and formats in porting from Alpha to Itanium so there is much less work in these areas in porting to x86-64. • As in any port to a new architecture, a number of architecture-defined interfaces that are critical to the inner workings of the operating system are being implemented. • OpenVMS is currently built for Alpha and Itanium from common source code modules. Support for x86-64 is being added, so all conditional assembly directives must be verified. • The boot manager for x86-64 has been upgraded to take advantage of new features and methods which did not exist when our previous implementation was created for Itanium. This will streamline the entire boot path and make it more flexible and maintainable. -

Migrating Mission-Critical Solutions to X86 Architecture How to Move Your Critical Workloads to Modern High-Availability Systems

Planning Guide Migrating Mission-Critical Solutions to x86 Architecture How to Move Your Critical Workloads to Modern High-Availability Systems Why You Should Read This Document This planning guide provides information to help you build the case for moving mission-critical workloads from legacy proprietary systems such as RISC/UNIX* to Intel® Xeon® processor-based solutions running Linux* or Windows* operating systems. • A brief summary of evolving data center challenges that impact mission-critical workloads • An overview of Intel server-based technology innovations that make Intel Xeon processor-based solutions an excellent choice for mission-critical computing environments • Practical guidance for building the business case for the migration of targeted mission-critical workloads • Steps for building a solid project plan for migration of mission-critical RISC/UNIX systems to modern, high-availability systems, including assessing the particular workload, conducting a proof of concept, and moving to production Contents 3 IT Imperatives: Deliver New Services Fast and Lower TCO 3 The Mission-Critical Migration Landscape 7 Build the Case for Migration: Eight Steps 10 Migration to x86 Architecture: Six Steps 12 Intel Resources for Learning More IT Imperatives: Deliver New Services Fast and Lower TCO Today, IT is being asked to provide new services much These newer systems combine lower costs with the faster, more cost-effectively, with better security to protect performance and availability that IT needs to support sensitive data, and with increased reliability. Budgets are mission-critical environments as well as implement key often flat or, at best, modestly increased. For mission-critical initiatives such as virtualization, cloud computing, and big workloads—those most important to the business— data analytics. -

X86 Intrinsics Cheat Sheet Jan Finis [email protected]

x86 Intrinsics Cheat Sheet Jan Finis [email protected] Bit Operations Conversions Boolean Logic Bit Shifting & Rotation Packed Conversions Convert all elements in a packed SSE register Reinterpet Casts Rounding Arithmetic Logic Shift Convert Float See also: Conversion to int Rotate Left/ Pack With S/D/I32 performs rounding implicitly Bool XOR Bool AND Bool NOT AND Bool OR Right Sign Extend Zero Extend 128bit Cast Shift Right Left/Right ≤64 16bit ↔ 32bit Saturation Conversion 128 SSE SSE SSE SSE Round up SSE2 xor SSE2 and SSE2 andnot SSE2 or SSE2 sra[i] SSE2 sl/rl[i] x86 _[l]rot[w]l/r CVT16 cvtX_Y SSE4.1 cvtX_Y SSE4.1 cvtX_Y SSE2 castX_Y si128,ps[SSE],pd si128,ps[SSE],pd si128,ps[SSE],pd si128,ps[SSE],pd epi16-64 epi16-64 (u16-64) ph ↔ ps SSE2 pack[u]s epi8-32 epu8-32 → epi8-32 SSE2 cvt[t]X_Y si128,ps/d (ceiling) mi xor_si128(mi a,mi b) mi and_si128(mi a,mi b) mi andnot_si128(mi a,mi b) mi or_si128(mi a,mi b) NOTE: Shifts elements right NOTE: Shifts elements left/ NOTE: Rotates bits in a left/ NOTE: Converts between 4x epi16,epi32 NOTE: Sign extends each NOTE: Zero extends each epi32,ps/d NOTE: Reinterpret casts !a & b while shifting in sign bits. right while shifting in zeros. right by a number of bits 16 bit floats and 4x 32 bit element from X to Y. Y must element from X to Y. Y must from X to Y. No operation is SSE4.1 ceil NOTE: Packs ints from two NOTE: Converts packed generated. -

Lecture 3: MIPS Instruction Set

Lecture 3: MIPS Instruction Set • Today’s topic: . Wrap-up of performance equations . MIPS instructions • HW1 is due on Thursday • TA office hours posted 1 A Primer on Clocks and Cycles 2 Performance Equation - I CPU execution time = CPU clock cycles x Clock cycle time Clock cycle time = 1 / Clock speed If a processor has a frequency of 3 GHz, the clock ticks 3 billion times in a second – as we’ll soon see, with each clock tick, one or more/less instructions may complete If a program runs for 10 seconds on a 3 GHz processor, how many clock cycles did it run for? If a program runs for 2 billion clock cycles on a 1.5 GHz processor, what is the execution time in seconds? 3 Performance Equation - II CPU clock cycles = number of instrs x avg clock cycles per instruction (CPI) Substituting in previous equation, Execution time = clock cycle time x number of instrs x avg CPI If a 2 GHz processor graduates an instruction every third cycle, how many instructions are there in a program that runs for 10 seconds? 4 Factors Influencing Performance Execution time = clock cycle time x number of instrs x avg CPI • Clock cycle time: manufacturing process (how fast is each transistor), how much work gets done in each pipeline stage (more on this later) • Number of instrs: the quality of the compiler and the instruction set architecture • CPI: the nature of each instruction and the quality of the architecture implementation 5 Example Execution time = clock cycle time x number of instrs x avg CPI Which of the following two systems is better? • A program is -

SIMD the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

SIMD The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Viktor Leis Outline 1. Why does SIMD exist? 2. How to use SIMD? 3. When does SIMD help? 1 Why Does SIMD Exist? Hardware Trends • for decades, single-threaded performance doubled every 18-22 months • during the last decade, single-threaded performance has been stagnating • clock rates stopped growing due to heat/end of Dennard’s scaling • number of transistors is still growing, used for: • large caches • many cores (thread parallelism) • SIMD (data parallelism) 2 Number of Cores AMD Rome 64 48 AMD Naples 32 cores Skylake SP Broadwell EX Broadwell EP Haswell EP 16 Ivy Bridge EX Ivy Bridge EP Nehalem (Westmere EX) Nehalem (Beckton) Sandy Bridge EP Core (Kentsfield) Core (Lynnfield) NetBurst (Foster) NetBurst (Paxville) 1 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 2020 year 3 Skylake CPU 4 Skylake Core 5 x86 SIMD History • 1997: MMX 64-bit (Pentium 1) • 1999: SSE 128-bit (Pentium 3) • 2011: AVX 256-bit float (Sandy Bridge) • 2013: AVX2 256-bit int (Haswell) • 2017: AVX-512 512 bit (Skylake Server) • instructions usually introduced by Intel • AMD typically followed quickly (except for AVX-512) 6 Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) • data parallelism exposed by the CPU’s instruction set • CPU register holds multiple fixed-size values (e.g., 4×32-bit) • instructions (e.g., addition) are performed on two such registers (e.g., executing 4 additions in one instruction) 42 1 7 + 31 6 2 = 73 7 9 7 Registers • SSE: 16×128 bit (XMM0...XMM15) • AVX: 16×256 bit (YMM0...YMM15) • AVX-512: 32×512 bit (ZMM0...ZMM31) • XMM0 is lower half -

State of Openembedded Internal Toolchain and Sdks

State of OpenEmbedded Internal Toolchain and SDKs Khem Raj Embedded Linux Conference 11-13 April 2011, San Fransisco Agenda ➢ Introduction ➢ Internal Toolchain ➢ Current state ➢ Features ➢ Pains ➢ SDKs ➢ Build your own SDK ➢ Using SDK ➢ Q & A 2 What is OpenEmbedded ? ➢ Framework to build Embedded Linux distributions ➢ Meta-data describing how to build software ➢ Includes tools to help build various RFS types. ➢ Learn more at http://www.openembedded.org ➢ http://wiki.openembedded.net/index.php/Mailing_lists ➢ IRC channel #oe on irc.freenode.net 3 Internal Toolchain ➢ GNU Toolchain based ➢ Supports C, C++, Fortran, objective-C ➢ Choice of system C libraries Glibc, eglibc, uClibc 4 Internal Toolchain ➢ Multiple versions of Toolchain components available ➢ GCC 4.5, 4.4, 4.3, 4.2 ➢ Glibc 2.10.1, 2.9 ➢ Eglibc 2.12, 2.11, 2.10, 2.9 ➢ uClibc 0.9.30, 0.9.31, git Option to select threading model (NPTL/LT) ➢ Distributions select sane combinations 5 Internal Toolchain Bootstrap Build required Bootstrap Rest of build Cross Native packages Cross process ToolchainToolchain External or prebuilt toolchain 6 Internal Toolchain ➢ Supports Multiple architectures ➢ ARM, MIPS/MIPS64, powerpc, x86, SuperH … ➢ Detects host include poisoning ➢ ARM ➢ Can be configured for hardfp or softfp floating ABI ➢ Chosen by setting ARM_FP_ABI = {hardfp|softfp} Only supported with gcc 4.5 ➢ Linaro gcc 4.5 improvements ➢ MIPS ➢ Configured with –with-mips-plt 7 Internal Toolchain Cross binutils GCC cross bootstrap stage 1 C Library headers/runtime Native sysroot GCC cross bootstrap stage 2 C Library(uClibc/eglibc/glibc) GCC cross Final 8 Internal Toolchain - Niggles ➢ Rebuilding not so straightforward ➢ Target support libraries and headers intertwined with cross compiler ➢ No support for multilibs 9 OpenEmbedded SDK ➢ Some SDKs pre-exist in OE metadata ➢ meta-toolchain, meta-toolchain-qte, meta-toolchain-shr etc.