The Ruth Crawford Seeger Sessions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aaron Copland: Famous American Composer, Copland Was Born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 1900. the Child of Jewish Immig

Aaron Copland: Famous American Composer, Copland was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 1900. The child of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, he first learned to play the piano from his older sister. At the age of sixteen he went to Manhattan to study with Rubin Goldmark, a respected private music instructor who taught Copland the fundamentals of counterpoint and composition. During these early years he immersed himself in contemporary classical music by attending performances at the New York Symphony and Brooklyn Academy of Music. He found, however, that like many other young musicians, he was attracted to the classical history and musicians of Europe. So, at the age of twenty, he left New York for the Summer School of Music for American Students at Fountainebleau, France. In France, Copland found a musical community unlike any he had known. While in Europe, Copeland met many of the important artists of the time, including the famous composer Serge Koussevitsky. Koussevitsky requested that Copland write a piece for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The piece, “Symphony for Organ and Orchestra” (1925) was Copland‟s entry into the life of professional American music. He followed this with “Music for the Theater” (1925) and “Piano Concerto” (1926), both of which relied heavily on the jazz idioms of the time. For Copland, jazz was the first genuinely American major musical movement. From jazz he hoped to draw the inspiration for a new type of symphonic music, one that could distinguish itself from the music of Europe. In the late 1920s Copland‟s attention turned to popular music of other countries. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Download a PDF of the Program

THE INAUGURATION OF CLAYTON S. ROSE Fifteenth President of Bowdoin College Saturday, October 17, 2015 10:30 a.m. Farley Field House Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine Bricks The pattern of brick used in these materials is derived from the brick of the terrace of the Walker Art Building, which houses the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. The Walker Art Building is an anchor of Bowdoin’s historic Quad, and it is a true architectural beauty. It is also a place full of life—on warm days, the terrace is the first place you will see students and others enjoying the sunshine—and it is standing on this brick that students both begin and end their time at Bowdoin. At the end of their orientation to the College, the incoming class gathers on the terrace for their first photo as a class, and at Commencement they walk across the terrace to shake the hand of Bowdoin’s president and receive their diplomas. Art by Nicole E. Faber ’16 ACADEMIC PROCESSION Bagpipes George Pulkkinen Pipe Major Grand Marshal Thomas E. Walsh Jr. ’83 President of the Alumni Council Student Marshal Bill De La Rosa ’16 Student Delegates Delegate Marshal Jennifer R. Scanlon Interim Dean for Academic Affairs and William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of the Humanities in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Delegates College Marshal Jean M. Yarbrough Gary M. Pendy Sr. Professor of Social Sciences Faculty and Staff Trustee Marshal Gregory E. Kerr ’79 Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Officers of Investiture President Clayton S. Rose The audience is asked to remain seated during the processional. -

NWCR714 Douglas Moore / Marion Bauer

NWCR714 Douglas Moore / Marion Bauer Cotillion Suite (1952) ................................................ (14:06) 5. I Grand March .......................................... (2:08) 6. II Polka ..................................................... (1:29) 7. III Waltz ................................................... (3:35) 8. IV Gallop .................................................. (2:01) 9. V Cake Walk ............................................ (1:56) 10. VI Quickstep ............................................ (2:57) The Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra; Alfredo Antonini, conductor Symphony in A (1945) .............................................. (19:15) 11. I Andante con moto; Allegro giusto ....... (7:18) 12. II Andante quieto semplice .................... (5:39) 13. III Allegretto ............................................ (2:26) 14. IV Allegro con spirito .............................. (3:52) Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra; William Strickland, conductor Marion Bauer (1887-1955) Prelude & Fugue for flute & strings (1948) ................ (7:27) 15. Prelude ..................................................... (5:45) 16. Fugue ........................................................ (1:42) Suite for String Orchestra (1955) ................... (14:47) 17. I Prelude ................................................... (6:50) Douglas Moore (1893-1969) 18. II Interlude ................................................ (4:41) Farm Journal (1948) ................................................. (14:20) 19. III Finale: Fugue -

Frank Buckley Walker

Frank Buckley Walker Columbia Records Old-Time Music Talent Scout Frank Buckley Walker (1889 – 1963) was the Artist and Repertoire (A & R) talent scout for Columbia Records’ Country Music Division during the 1920s and 1930s. Along with Ralph Peer of Victor Records, Walker mastered the technique of field recordings. Specializing in southern roots music, Walker set up remote recording studios in cities such as Atlanta, New Orleans, Memphis, Dallas, Little Rock and Johnson City searching for amateur musical talent. The fascinating interview below with Frank Buckley Walker was done by Mike Seeger on June 19, 1962. The interview provides insight into the early era of recorded music as well as the evolution of country music as a market segment. Frank Buckley Walker June 19, 1962 The Seeger-Walker Interview MS (Mike Seeger): I was noticing this Jaw’s Harp, or Jew’s Harp on your desk here…… FW (Frank Walker): Jew’s Harp is what they call it. It’s an old one. And you were telling me it dates back to your early days, where was it, Fly…? Fly Summit, New York on a farm. Fly Summit was a metropolis. It had about four or five houses, a church, a baling machine, and one little store. We lived on a farm about a mile away from there. And the Jew’s Harp - that played an important part because it was the only thing I could play other than the 1 harmonica. But it did get me a few pennies here and there for playing for some sorts of entertainment we had amongst the farmers. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Women Pioneers of American Music Program

Mimi Stillman, Artistic Director Women Pioneers of American Music The Americas Project Top l to r: Marion Bauer, Amy Beach, Ruth Crawford Seeger / Bottom l to r: Jennifer Higdon, Andrea Clearfield Sunday, January 24, 2016 at 3:00pm Field Concert Hall Curtis Institute of Music 1726 Locust Street, Philadelphia Charles Abramovic Mimi Stillman Nathan Vickery Sarah Shafer We are grateful to the William Penn Foundation and the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia for their support of The Americas Project. ProgramProgram:: WoWoWomenWo men Pioneers of American Music Dolce Suono Ensemble: Sarah Shafer, soprano – Mimi Stillman, flute Nathan Vickery, cello – Charles Abramovic, piano Prelude and Fugue, Op. 43, for Flute and Piano Marion Bauer (1882-1955) Stillman, Abramovic Prelude for Piano in B Minor, Op. 15, No. 5 Marion Bauer Abramovic Two Pieces for Flute, Cello, and Piano, Op. 90 Amy Beach (1867-1944) Pastorale Caprice Stillman, Vickery, Abramovic Songs Jennifer Higdon (1962) Morning opens Breaking Threaded To Home Falling Deeper Shafer, Abramovic Spirit Island: Variations on a Dream for Flute, Cello, and Piano Andrea Clearfield (1960) I – II Stillman, Vickery, Abramovic INTERMISSION Prelude for Piano #6 Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953) Study in Mixed Accents Abramovic Animal Folk Songs for Children Ruth Crawford Seeger Little Bird – Frog He Went A-Courtin' – My Horses Ain't Hungry – I Bought Me a Cat Shafer, Abramovic Romance for Violin and Piano, Op. 23 (arr. Stillman) Amy Beach June, from Four Songs, Op. 53, No. 3, for Voice, Violin, and -

1 Cultual Analysis and Post-Tonal Music

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-02843-1 - Gendering Musical Modernism: The Music of Ruth Crawford, Marion Bauer, and Miriam Gideon Ellie M. Hisama Excerpt More information 1 CULTUAL ANALYSIS AND POST-TONAL MUSIC Given the vast, marvelous repertoire of feminist approaches to literary analysis introduced over the past two decades, a music theorist interested in bringing femi- nist thought to a project of analyzing music by women might do well to look first to literary theory. One potentially useful study is Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s landmark work The Madwoman in the Attic, which asserts that nineteenth-century writing by women constitutes a literary tradition separate and distinct from the writing of men and argues more specifically that writings of women, including Austen, Shelley, and Dickinson, share common themes of alienation and enclo- sure.1 Some feminist theorists have claimed that a distinctive female tradition exists also in modernist literature; Jan Montefiore, for example, asserts that in autobio- graphical writings of the 1930s, male modernists tended to portray their experi- ences as universal in contrast to female modernists who tended to represent their experiences as marginal.2 But because of the singular nature of the modernist, post-tonal musical idiom, an analytical project intended to explore whether a distinctive female tradition indeed exists in music immediately runs aground. Unlike tonal compositions, which draw their structural principles from a more or less unified compositional language, post- tonal works are constructed according to highly individualized schemes whose meaning and coherence derive from their internal structure rather than from their relation to a body of works. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

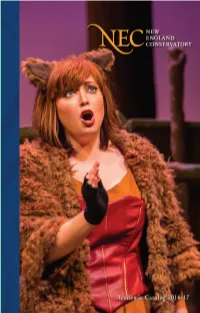

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94

Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 By Jon Pareles, The New York Times, 1/28 Pete Seeger, the singer, folk-song collector and songwriter who spearheaded an American folk revival and spent a long career championing folk music as both a vital heritage and a catalyst for social change, died Monday. He was 94 and lived in Beacon, N.Y. His death was confirmed by his grandson, Kitama Cahill Jackson, who said he died of natural causes at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Mr. Seeger’s career carried him from singing at labor rallies to the Top 10 to college auditoriums to folk festivals, and from a conviction for contempt of Congress (after defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s) to performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at an inaugural concert for Barack Obama. 1 / 13 Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 For Mr. Seeger, folk music and a sense of community were inseparable, and where he saw a community, he saw the possibility of political action. In his hearty tenor, Mr. Seeger, a beanpole of a man who most often played 12-string guitar or five-string banjo, sang topical songs and children’s songs, humorous tunes and earnest anthems, always encouraging listeners to join in. His agenda paralleled the concerns of the American left: He sang for the labor movement in the 1940s and 1950s, for civil rights marches and anti-Vietnam War rallies in the 1960s, and for environmental and antiwar causes in the 1970s and beyond.