CORSETS and CRINOLINES Page Intentionally Left Blank Frontispiece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clothing and Power in the Royal World of Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Elizabeth I)

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Inquiry Journal 2020 Inquiry Journal Spring 4-10-2020 Clothing and Power in the Royal World of Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Elizabeth I) Niki Toy-Caron University of New Hampshire Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/inquiry_2020 Recommended Citation Toy-Caron, Niki, "Clothing and Power in the Royal World of Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Elizabeth I)" (2020). Inquiry Journal. 10. https://scholars.unh.edu/inquiry_2020/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Inquiry Journal at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inquiry Journal 2020 by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. journal INQUIRY www.unh.edu/inquiryjournal 2020 Research Article Clothing and Power in the Royal World of Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Elizabeth I —Niki Toy-Caron At President Trump’s 2019 State of the Union speech, “the women of the US Democratic party dressed in unanimous white” to make “a powerful statement that the status quo in Washington will be challenged” (Independent 2019). In the 1960s, women burned bras in support of women’s rights. In the late 1500s, Queen Elizabeth I took the reins of England, despite opposition, by creating a powerful image using clothing as one of her tools. These are only a few examples of how women throughout history have used clothing to advance their agenda, form their own alliances, and defend their interests. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Spanish Farthingale Dress

Spanish Farthingale Dress This dress has a separate bodice, under skirt and over skirt, as well as a partlet at the neck.. The bodice opens in the back, the under skirt opens at the side, and the over skirt opens in the front. There are no fitting seams in the bodice. Although I did not add boning to the bodice, you certainly could. It would help to keep the front point down and add some body to the front of the bodice. The under skirt was made with muslin in the back to conserve fabric, which was certainly done in the 16th Century. The over skirt closes in the front under the point of the bodice. The straight sleeves have a gathered cap. This dress is worn with a Spanish farthingale and can also have a bum roll in the back for the support of the cartridge pleating. (see the bum roll pattern under the French Farthingale Dress Spanish Farthingale Cut 2 from each of the pattern pieces, adding ¼” for seam allowance (This can be made using muslin or similar fabric) When tracing the pattern, make sure that you mark all of the lines for the boning. Sew the seams for each set of the pattern so that you end up with two single layer farthingale skirts. Then stitch the two together at the bottom with right sides together. Finish the side openings by turning the seam allowance in and hand or machine stitching it closed. The top is finished with a piece of bias tape, leaving enough at the sides in order to tie the farthingale into place. -

Jacobean Costume

ROOM 5 & The Long Gallery Jacobean Costume The constricting and exaggerated fashions of the Elizabethan era continued into the early part of the seventeenth century. Women still wore tightly boned bodices with elongated ‘stomachers’ (an inverted triangle of stiffened material worn down over the stomach) and enormous skirts that encased the lower part of their bodies like cages. However, by 1620 the excessive padding around the hips of both sexes had disappeared, and fashion began to slim down and adopt a longer, more elegant line. The doublet became more triangular in shape and the huge cartwheel ruff gave way to a falling collar, edged with lace. The Long Gallery From the 1580s the Spanish farthingale, or portrait of James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, hooped petticoat, was superseded by the who wears an elegant black and gold costume, French farthingale, a wheel-like structure that heavily embroidered with gold and silver held the skirt out like a drum. It can be seen thread, with a standing linen collar of cutwork to great effect in the portrait of Lucy Russell, and matching cuffs. Countess of Bedford. This was a style of dress expected at the court as Anne of Denmark, King James’ Queen, admired its formality. The Countess is dressed for the coronation of James I and Anne of Denmark, in a costume of rich red velvet, lavishly lined and trimmed with ermine. Lucy Russell, Countess of Bedford Robert Carey and Elizabeth Trevannion, (NPG 5688) 1st Earl and Countess of Monmouth and – Long Gallery their family (NPG 5246) – Long Gallery This rare family group shows a variety of ruffs The portrait of Sir Walter Ralegh and his son worn at this date. -

French Farthingale Renaissance Dress

French Farthingale Renaissance Dress The French Farthingale Dress was worn primarily in Northern Europe in the 16th century. The skirt over the farthingale was quite wide and made from a continuous piece of fabric, which was tucked up to form a ruffle on top of the farthingale. The sleeves were cut wide at the top to off set the size of the skirt. The ruffle at the neck also added height and width to the upper body. This pattern is based in the pattern from The Tudor Tailor, but altered to meet the needs of my ½ scale dress form French Farthingale Cut out two sets of the pattern using muslin (for the top and the bottom) using a ¼” seam allowance Cut out the pattern using a heavy batting or bottom weight material (used in the middle) with no seam allowance 1. Stitch the farthingale together on the outside and the inside edges, layering them Muslin/Muslin/Batting. Turn them so that the batting is in the middle and the two muslin fabrics are the top and the bottom. 2. On only one of the sides, turn the seam allowance under and stitch to close the end of the farthingale (this is at center back) 3. Stitch the boning oval lines into the farthingale. You will notice that one side of the center back is closed and the other side is open. The open side is where you will insert the boning. 4. Mark a grid work of lines that are ½” apart across the entire farthingale. Then quilt these lines, making sure that you do not stitch over the boning lines. -

25831 Regalos Par El Rey Del Bosque

Oliver Noble Wood, Jeremy Roe y Jeremy Lawrance The spread across Europe of the modes of dress adopted at the Spanish court Studies on international relations in the field of (dirs.), Poder y saber. Bibliotecas y bibliofilia en la época was a major cultural phenomenon that reached its height between 1550 and I SPANISH FASHION Spanish Golden Age art, literature and thought. del conde-duque de Olivares 1650 as a result of the world hegemony enjoyed by the Habsburgs. This at the Courts of Early Modern Europe Monographs, doctoral theses and conference unique book is the first interdisciplinary study to examine the distinguishing papers focusing on aspects of mutual influence, Giuseppe Galasso, Carlos V y la España imperial. Estudios features of Spanish fashion, as well as the various political, ceremonial and SPANISH FASHION y ensayos VOLUME I parallels and exchanges between Spain and other protocol factors that exported this model to the rest of the continent. countries; ideas, forms, agents and episodes relating Alfonso de Vicente y Pilar Tomás (dirs.), Tomás Luis to the Spanish presence in Europe, and that of Some thirty international experts guide readers through the history of ••• de Victoria y la cultura musical en la España de Felipe III Europe in Spain. costume and textiles during the period Spanish fashion enjoyed influence Edited by JOSÉ LUIS COLOMER and AMALIA DESCALZO Vicente Lleó, Nueva Roma. Mitología y humanismo en el within and beyond the boundaries of the Spanish Monarchy. This profusely Renacimiento sevillamo illustrated collection of essays makes a highly significant contribution to the Mercedes Blanco, Góngora heroico. -

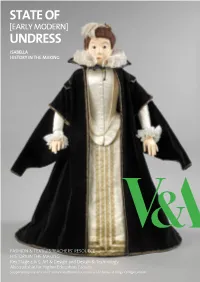

History in the Making – Isabella

ISABELLA HISTORY IN THE MAKING FASHION & TEXTILES TEACHERS’ RESOURCE HISTORY IN THE MAKING Key Stage 4 & 5: Art & Design and Design & Technology Also suitable for Higher Education Groups Supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council with thanks to Kings College London 1 FOREPART (PANEL) LIMEWOOD MANNEQUIN BODICE CHOPINES (SHOES) SLEEVE RUFFS GOWN NECK RUFF & REBATO HEADTIRE FARTHINGALE STOCKINGS & GARTERS WIG SMOCK 2 3 4 5 Contents Introduction: Early Modern Dress 9 Archduchess Isabella 11 Isabella undressing / dressing guide 12 Early Modern Materials 38 6 7 Introduction Early Modern Dress For men as well as women, movement was restricted in the Early Modern period, and as you’ll discover, required several The era of Early Modern dress spans between the 1500s to pairs of hands to put on. the 1800s. In different countries garments and tastes varied hugely and changed throughout the period. Despite this variation, there was a distinct style that is recognisable to us today and from which we can learn considerable amounts in terms of design, pattern cutting and construction techniques. Our focus is Europe, particularly Belgium, Spain, Austria and the Netherlands, where our characters Isabella and Albert lived or were connected to during their reign. This booklet includes a brief introduction to Isabella and Albert and a step-by-step guide to undressing and dressing them in order to gain an understanding of the detail and complexity of the garments, shoes and accessories during the period. The clothes you see would often be found in the Spanish courts, and although Isabella and Albert weren’t particularly the ‘trend-setters’ of their day, their garments are a great example of what was worn by the wealthy during the late 16th and early 17th centuries in Europe. -

Fur Dress, Art, and Class Identity in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England and Holland by Elizabeth Mcfadden a Dissertatio

Fur Dress, Art, and Class Identity in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England and Holland By Elizabeth McFadden A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art and the Designated Emphasis in Dutch Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elizabeth Honig, Chair Professor Todd Olson Professor Margaretta Lovell Professor Jeroen Dewulf Fall 2019 Abstract Fur Dress, Art, and Class Identity in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England and Holland by Elizabeth McFadden Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art Designated Emphasis in Dutch Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Elizabeth Honig, Chair My dissertation examines painted representations of fur clothing in early modern England and the Netherlands. Looking at portraits of elites and urban professionals from 1509 to 1670, I argue that fur dress played a fundamentally important role in actively remaking the image of middle- class and noble subjects. While demonstrating that fur was important to establishing male authority in court culture, my project shows that, by the late sixteenth century, the iconographic status and fashionability of fur garments were changing, rendering furs less central to elite displays of magnificence and more apt to bourgeois demonstrations of virtue and gravitas. This project explores the changing meanings of fur dress as it moved over the bodies of different social groups, male and female, European and non-European. My project deploys methods from several disciplines to discuss how fur’s shifting status was related to emerging technologies in art and fashion, new concepts of luxury, and contemporary knowledge in medicine and health. -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V3_930 3/5/04 3:57 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V3_930 3/5/04 3:57 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 3: European Culture from the Renaissance to the Modern3 Era SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos. -

Modus Anglorum 2017

Contents Incipit p.2 Eyeglasses p.16 Getting Started p.2 Cosmetics p.16 Costume Etiquette p.3 Dramatis Personae p.3 APPENDICES Bibliography p.17 BASICS Glossary p.18 Colours p.4 Patterns p.22 Fabrics p.4 The Contract p.24 Trims p.5 Blank sketch figures p.26 Construction p.6 UNDERWEAR Shirts & Smocks p.6 Farthingales, Stays, & Other Underpinnings p.7 Stockings p.7 Shoes p.7 OUTER GARMENTS Doublets & Jerkins p.8 Nether Garments: Trunk Hose & Venetians p.9 Cloaks & Gowns p.9 Bodices p.10 Partlets p.10 "But speake, I praie: vvho ist vvould gess or skann Skirts & Foreparts p.11 Surcoats p.11 Fantasmus to be borne an Englishman? Sleeves p.12 Hees hatted Spanyard like and bearded too, Buttons p.12 Ruft Itallyon-like, pac'd like them also: ACCESSORIES His hose and doublets French: his bootes and shœs Hats p.12 Are fashiond Pole in heels, but French in tœs. Ruffs p.13 Oh! hees complete: vvhat shall I descant on? Jewellery p.14 A compleate Foole? nœ, compleate Englishe man." Fans p.15 Weapons p.15 William Goddard, A Neaste of Waspes, 1615 Belts p.15 ❦ Other Accessories p.15 Hairstyles p.16 !1 Incipit The customers at our events have two ways of learning who we are: what we wear and what we say. They perceive us first by what we wear, and often this is the only input they get from us. Therefore, we must convey as much information as possible about ourselves by our clothing. It is traditional in the Elizabethan era and in the Guild of St. -

In Pursuit of the Fashion Silhouette

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Fillmer, Carel (2010) The shaping of women's bodies: in pursuit of the fashion silhouette. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29138/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29138/ THE SHAPING OF WOMEN’S BODIES: IN PURSUIT OF THE FASHION SILHOUETTE Thesis submitted by CAREL FILLMER B.A. (ArtDes) Wimbledon College of Art, London GradDip (VisArt) COFA UNSW for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Arts and Social Sciences James Cook University November 2010 Dedicated to my family Betty, David, Katheryn and Galen ii STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. Signature Date iii ELECTRONIC COPY I, the undersigned, the author of this work, declare that the electronic copy of this thesis provided to the James Cook University Library is an accurate copy of the print thesis submitted, within the limits of the technology available.