Land Use Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

1 All Rights Reserved Do Not Reproduce in Any Form Or

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DO NOT REPRODUCE IN ANY FORM OR QUOTE WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION 1 2 Tactical Cities: Negotiating Violence in Karachi, Pakistan by Huma Yusuf A.B. English and American Literature and Language Harvard University, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © Huma Yusuf. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ Shankar Raman Associate Professor of Literature Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies 3 4 Tactical Cities: Negotiating Violence in Karachi, Pakistan by Huma Yusuf Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in Science in Comparative Media Studies. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the relationship between violence and urbanity. Using Karachi, Pakistan, as a case study, it asks how violent cities are imagined and experienced by their residents. The thesis draws on a variety of theoretical and epistemological frameworks from urban studies to analyze the social and historical processes of urbanization that have led to the perception of Karachi as a city of violence. It then uses the distinction that Michel de Certeau draws between strategy and tactic in his seminal work The Practice of Everyday Life to analyze how Karachiites inhabit, imagine, and invent their city in the midst of – and in spite of – ongoing urban violence. -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

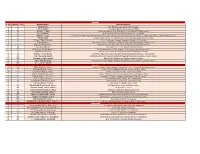

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Code Name CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Nature of Deposit

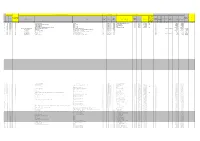

DETAILS OF THE BRANCH DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/Provi NAME OF THE PROVINCE IN ncial Last date of deposit or S. No WHICH ACCOUNT OPENED / withdrawal (DD- Remarks Account Type ISNTRUMENT PAYABLE Instrument Type (FED/PRO) In Currency MON-YYYY) Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, Rate Type FCS Contract Rate of PKR Rate applied date code Name CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number Name of the Applicant/Purchaser (DD,PO,FDD,TD Instrument No. Date of Issue (USD,EUR,GBP,AE Amount Outstanding Eqv.PKR surrendered (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed or any Case of (MTM,FCSR) No (if any) conversion (DD-MON-YYYY) R,CO) D,JPY,CHF) other) Instrument favoring the Government 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 791 Lahore PB CMA (POF) Wah Cantt Wah Cantt LCY 1052695-00-0 Current Fresenius Medical Care pakistan Pvt Ltd PO 394760 9/14/2009 FED PKR 7,200.00 7,200.00 2 791 Lahore PB Pakistan International AirlineLlahore Airport Lahore-Pakistan LCY 1038462-00-0 Current KSB Pumps Co Ltd PO 395643 11/11/2009 FED PKR 1,000.00 1,000.00 3 791 Lahore PB Yaaseen Shipping Lines Karachi LCY 1041029-00-0 Current Escorts Pakistan Ltd PO 392581 5/14/2009 PKR 1,800.00 1,800.00 4 791 Lahore PB Ahmed Waheed Malik Lahore-Pakistan LCY 0190751-00-0 Current CRES PO 383470 4/13/2009 PKR 73.00 73.00 5 791 Lahore PB The Chief Purchase officer,Health Department,Govt of Punjab Lahore-Pakistan LCY 0056481-00-0 Current B Braun Pakistan Pvt Ltd PO 395718 11/18/2009 -

12086393 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Karachi Transportation Improvement Project ................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Background................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1.2 Work Items ................................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.3 Work Schedule ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Progress of the Household Interview Survey (HIS) .......................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Seminar & Workshop ........................................................................................................................ 1-5 1.4 Supplementary Survey ....................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1 Topographic and Utility Survey................................................................................................. 1-6 1.4.2 Water Quality Survey ............................................................................................................... -

TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-E - Faisal

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Karachi TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-e - Faisal. 0316-9992201 2 Karachi TCS Office Main Head 101-104 CAA Club Road Near Hajj Tarminal - 3 0316-9992202 3 Karachi TCS Office Malir Cantt Shop#180 S-13 Cantt Bazar, Malir Cantonement, Karachi 0316-9992204 4 Karachi TCS Office Malir Court Shop # G-14 Al Raza Sq. New Malir City Near Malir Court 0316-9992207 Shop # 3Haq Baho shopping Center Gulshan e Hadeed Ph.1 Gulshan e 5 Karachi TCS Office Gulshan-E-Hadeed 0316-9992213 Hadeed 6 Karachi TCS Office Korangi No. 4 Shop # 10, Abbasi Fair Trade Centre, Korangi # 4 Opp. KMC Zoo 0316-9992215 7 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN Chowrangi Shop A 1/30, block No 5. Haider plaza gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi 0316-9992230 8 Karachi TCS Office GULISTAN-E-JOHAR Shop # Saima Classic Rashid Minas Road Near Johar More 0316-9992231 9 Karachi TCS Office HYDRI Shop # B-13, Al Bohran Circle, Block-B, North Nazimabad. 0316-9992232 10 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN-E-IQBAL Shop # 06, Plot # B-74 Shelzon Center BI.15 Opp. Usmania Restrent 0316-9992234 11 Karachi TCS Office ORANGI TOWN Banaras Town, Sector 8, Orangi Town Karachi Opp. Banaras Town Masjid 0316-9992236 12 Karachi TCS Office S.I.T.E Shop # 5, SITE Shopping Centre, Manghopir Rd. Opp. MCB SITE Br. 0316-9992237 13 Karachi TCS Office NIPA CHOWRANGI Shop # A -8 KDA Overseas apartment 0316-9992241 S 5 Noman Arcade Bl. 14 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Near Mashriq Centre Sir 14 Karachi TCS Office Mashriq Center 0316-9992250 suleman shah Rd. -

S. NO Branch Code Branch Name Branch Address 1 5 Karachi Main B.A

Karachi S. NO Branch Code Branch Name Branch Address 1 5 Karachi Main B.A. Building, I.I.Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 31 Clifton Branch Plot # BC-6, Block 9, Clifton, Karachi, 75600 3 30 Shahrah e Faisal Progressive Square, 11-A, Main Shahra-e-Faisal Block 6, PECHS, Karachi 4 19 S.I.T.E Branch D-40, Estate Avenue, Siemens Chowrangi, S.I.T.E., Karachi 5 11 Gulshan e Iqbal Plot No.SB-15, Block 13-B, KDA Scheme No.24, University Road, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi & Flat No.3, Sumera Apartments, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi. 6 16 Bahadurabad Prime Arcade, Shop No. 1-3, Bahadur Shah Zafar Road, Bahadurabad, Karachi-74800 7 14 Defence Phase V Branch C-12-C, 26th Street, Tauheed Commercial, Phase V, DHA, Karachi 8 4 Federal B Area C-28, Block - 13, K.D.A. Scheme 16, Federal 'B' Area, Shahrah-e-Pakistan, Karachi - 75950. 9 23 Korangi Industrial Area Aiwan-e-Sanat, Plot No.ST-4/2, Sector 23, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi 10 89 Tariq Road Branch 124/A, Block 2, P.E.C.H.S., Main Tariq Road, Karachi 11 232 Abul Hasan Isphani Branch Sani Corner, Sector-22, KDA Scheme 33, Abul Hasan Isphani Road, Karachi 12 22 DHA Phase I Branch Plot No. 119, Hall No. G-2, Main Korangi Road, DHA Phase I, Karachi 13 17 Gulistan e Johar Branch Yasir Plaza, Block 10-A, Scheme 45, Main Rashid Minhas Road, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi 14 189 Johar Chowrangi Branch Plot# 118-119-C/1 K.D.A Scheme No.36 Rufi Shopping Mall, Block 18, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi 15 303 Khayaban e Rahat Branch Plot No. -

"The Port Qasim Authority (Amendment) Bilt,2019"

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT PRESS RELEASE Islamabad the 2Sthseptember, 2020: 10th meeting of the Standing Committee on Maritime Affairs was held in Committee Room No.7, Parliament House, at 10:30 am under the Chairmanship of Mir Amer Ali Khan Magsi, MNA. The agenda of the meeting was circulated vide Notice No.F.8 (l)/2020-Com-l dated 17th September,2020. 2. The issue of containers stuck up at sea ports of Pakistan without any justification and also penalties imposed by foreign shipping companies and private terminal operators at ports for consignment arriving in Pakistan during lockdown period, was taken up by the Members of the Standing Committee Vice President of FPCCI and representative of Lahore Chamber of Commerce. It was told that although, an order was issued by the Director General of Shipping advising shipping lines not to impose container detention charges on import shipments but these are not only imposed and demurrage are also asked to be paid in billions. In other parts of the region, this has been waived off during the lockdown period of COVID-I9. The Committee vowed to take up this matter in the next scheduled meeting for the redressal ofgrievances. 3. The bills "The Port Qasim Authority (Amendment) Bilt,2019" and "The Gawadar Port Authority (Amendment) Bill,2019", were deferred for the next meeting in order to have more clarity from the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Ministry of Law & Justice. 4. The meeting was attended by MNA's Mr. Muhammad Yaqoob Shaikh, Rana Muhammad Qasim Noon, Mr. Faheem Khan, Mr. Saif Ur Rehman, Mr. -

East Bengal Tables , Vol-8, Pakistan

M-Int 17 5r CENSlUJS Of PAIK~STAN, ~95~ VOLUME 6 REPORT & TABLES BY GUl HASSAN, M. I. ABBASI Provincial Superintendent of Census, SIND Published by the Man.ager of Publication. Price Rs. J 01-1- FIRST CENSUS OF PAKISTAN. 1951 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS Bulletins No. I--Provisional Tables of Population. No. 2--Population according to Religion. No.3-Urban and Rural Population and Area. No.4-Population according to Economic Categories. Village Lists The Village list shows the name of every Village in Pakistan in its place in the ltthniftistra tives organisation of Tehsils, Halquas, Talukas, Tapas, SUb-division's Thanas etc. The names are given in English and in the appropriate vernacular script, and against _each is shown the area, population as enumerated in the Census, tbe number of houses, and local details such as the existence of Railway Stations, Post Offices, Schools, Hospitals etc. The Village -list. is issued in separate booklets for each District or group of Districts. Census Reports Printed Vol. 2-Baluchistan and States Union Report and Tables. Vol. 3.-East Bengal Report and Tables. Vol. 4-N.-W. F. P. and Frontier Regions Report :md Tables. Vol. 6-Sind and Khairpur State Report and Tabla Vol 8-East Pakistan Tables of Economic CharacUi Census Reports (in course of preparation.) Vol. I-General Report and Tables for Pakistan, shcW)J:}g Provincial Totals. Vol. 5-Punjab and Bahawalpur State Report and Tables. Vol. 7-West Pakistan Tables ot Economic Characteristics.- PREF ACE, This Census Report for the province of Sind and Khairpur State is one of the series 'of volumes in which the results ofothe 1951 €ensus of Pakistan are recorded. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

East-Karachi

East-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 East Karachi Jamshed Town 1-Akhtar Colony 408070173 GBLSS - H.M.A. Middle Mixed 7,841 1,568 4,705 3,137 1,568 6,273 25,093 6,273 31,366 2 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070139 GBPS - BILAL MASJID NO.2 Primary Mixed 12,559 2,512 10,047 2,512 2,512 10,047 40,189 10,047 50,236 3 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070174 GBLSS - UNION Middle Mixed 16,613 3,323 13,290 3,323 3,323 13,290 53,161 13,290 66,451 4 East Karachi Jamshed Town 9-Central Jacob Line 408070171 GBLSS - BATOOL GOVT` BOYS`L/SEC SCHOOL Middle Mixed 12,646 2,529 10,117 2,529 2,529 10,117 40,466 10,117 50,583 5 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070160 GBLSS - AZMAT-I-ISLAM Middle Boys 22,422 4,484 17,937 4,484 4,484 17,937 71,749 17,937 89,687 6 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070162 GBLSS - RANA ACADEMY Middle Boys 13,431 2,686 8,059 5,372 2,686 10,745 42,980 10,745 53,724 7 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070163 GBLSS - MAHMOODABAD Middle Boys 20,574 4,115 12,344 8,230 4,115 16,459 65,836 16,459 82,295 8 East Karachi Jamshed Town 11-Garden East 408070172 GBLSS - GULSHAN E FATIMA Middle Mixed 16,665 3,333 13,332 3,333 3,333 13,332 53,327 13,332 66,658 9 East Karachi Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town 3-PIB