Cathedral of St. Augustine Was Originally Published in the St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

The Two-Piece Corinthian Capital and the Working Practice of Greek and Roman Masons

The two-piece Corinthian capital and the working practice of Greek and Roman masons Seth G. Bernard This paper is a first attempt to understand a particular feature of the Corinthian order: the fashioning of a single capital out of two separate blocks of stone (fig. 1).1 This is a detail of a detail, a single element of one of the most richly decorated of all Classical architec- tural orders. Indeed, the Corinthian order and the capitals in particular have been a mod- ern topic of interest since Palladio, which is to say, for a very long time. Already prior to the Second World War, Luigi Crema (1938) sug- gested the utility of the creation of a scholarly corpus of capitals in the Greco-Roman Mediter- ranean, and especially since the 1970s, the out- flow of scholarly articles and monographs on the subject has continued without pause. The basis for the majority of this work has beenformal criteria: discussion of the Corinthian capital has restedabove all onstyle and carving technique, on the mathematical proportional relationships of the capital’s design, and on analysis of the various carved components. Much of this work carries on the tradition of the Italian art critic Giovanni Morelli whereby a class of object may be reduced to an aggregation of details and elements of Fig. 1: A two-piece Corinthian capital. which, once collected and sorted, can help to de- Flavian period repairs to structures related to termine workshop attributions, regional varia- it on the west side of the Forum in Rome, tions,and ultimatelychronological progressions.2 second half of the first century CE (photo by author). -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Architecture, Power, and National Identity

Architecture, Power, and National Identity Second edition This new, expanded edition of Architecture, Power, and National Identity examines how architecture and urban design have been manipulated in the service of politics. Focusing on the desigq .?fparliamentary complexes in capital cities across the world, it shows how these places reveal the struggles for power and identity in multicultural natiortstates. Building on the prize-winning first edition, Vale updates the text and illustrations to account for recent sociopolitical changes, inciudesdisCl.lssion of several newly built places, and assesses the enhanced concerns for security that have preoccupied regimes in politically volatile countries. Th~ book is truly glob<l;l in scope, looking at capital cities in North America and Europe, as well as in India, Brazil, Sri Lanka, Kuwait, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Tanzania, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Ultimately, Vale presents an engaging, incisive combination of history, politics, and architecture to chart the evolution of state power and national identity, updated for the twenty-first century. Lawrence Vale is the Head of the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. He has published six previous books, including the first edition of Architecture, Power, and National Identity, which received the Spiro Kostof Award from the Society of Architectural Historians. Praise for the first edition: "Lawrence Vale's Architecture, Power, and National Identity is a powerful and compelling work and is a major contribution to the history of urban form." David Gosling, Town Planning Review "[Vale's] book makes fascinating reading for anyone interested in the cultural forces behind architecture and urban design and in the ways that parliamentary and other major government buildings are emblematic of the political history and power elites of their countries. -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 63 Number 4 Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume Article 1 63, Number 4 1984 Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1984) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 63 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol63/iss4/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Published by STARS, 1984 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 63 [1984], No. 4, Art. 1 COVER Opening joint session of the Florida legislature in 1953. It is traditional for flowers to be sent to legislators on this occasion, and for wives to be seated on the floor. Florida’s cabinet is seated just below the speaker’s dais. Secretary of State Robert A. Gray is presiding for ailing Governor Dan T. McCarty. Photograph courtesy of the Florida State Archives. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol63/iss4/1 2 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Volume LXIII, Number 4 April 1985 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1985 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. Second class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. Printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. -

Byzantine Architecture History of Architecture

Byzantine Architecture History of Architecture No’man Bayaty Introduction • Byzantium (Constantinople) became the new capital in 324 A.D. • The location of Constantinople (Istanbul) is the finest in Europe. • It sits on the strait of Marmara, one of the very strategic locations. • The separation of the Roman empire accompanied a separation in religion, with the separation of the Christian church. • The difference in belief and rituals between the eastern and western church led to some differences in architecture also. • At the time of the emperor Justinian (527-565 A.D.), Italy became under the rule of the Byzantine empire. Introduction • The place is poor in terms of building materials (stone and mud are available), but had some marble, which was used and exported. • The climate was hotter than Rome, which added to the oriental character of the architecture of the place. • The term Byzantine architecture is used to describe the architecture of the empire, and sometimes also to describe the buildings built in the western empire but within the same style. • The style continued to thrive in Constantinople until it fell under the hands of the Ottomans in 1453 A. D., and became the capital of their empire. Architectural Character S. Sophia, Constantinople. Architectural Character • The most important feature that would control the form of this style is the development of the (dome architecture). • This led to adopting central shapes, like circular or octagonal plans. • They developed (Pendentives) as vaulting system. • The structural elements were usually built with a marble shell, and filled with brick (close to the Roman concrete technique). -

Lambs of God: the Untold Story of African American Children Who Desegregated Catholic Schools in New Orleans

LAMBS OF GOD: THE UNTOLD STORY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN WHO DESEGREGATED CATHOLIC SCHOOLS IN NEW ORLEANS by Terri A. Dickerson A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate F acuity of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Conflict Analysis and Resolution Chair Program Director Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Lambs of God: The Untold Story of African American Children Who Desegregated Catholic Schools in New Orleans A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Terri A. Dickerson Master of Arts Johns Hopkins University, 1997 Bachelor of Science University of Virginia, 1979 Director: Patricia Maulden, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION-NODERIVS 3.0 UNPORTED LICENSE. ii Dedication For Kevin to whom I casually mentioned that I would like to conduct this research. He encouraged me to do it, and has been with me every step of the way, always willing to let me test my plans and theories against his brilliant mind. Without his love, optimism and support, this work would not have been accomplished. iii Acknowledgements I thank my husband Kevin, who has been my biggest support throughout, along with CJ, James, and Devon, who are always sources of wonderment and pride. Special thanks to George Mason University for granting me the 2016 Provost’s Award as well as the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution for the 2015 James Lauie Award and 2016 Alumni Award. -

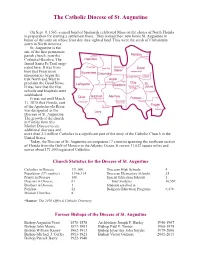

St. Augustine Statistics

The Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine On Sept. 8, 1565, a small band of Spaniards celebrated Mass on the shores of North Florida in preparation for starting a settlement there. They named their new home St. Augustine in honor of the saint on whose feast day they sighted land. Thus were the seeds of Christianity sown in North America. St. Augustine is the site of the first permanent parish church, now the Cathedral-Basilica. The famed Santa Fe Trail origi- nated here. It was from here that Franciscan missionaries began the trek North and West to proclaim the Good News. It was here that the first schools and hospitals were established. It was not until March 11, 1870 that Florida, east of the Apalachicola River, was designated as the Diocese of St. Augustine. The growth of the church in Florida from this Mother Diocese to six additional dioceses and more than 2.1 million Catholics is a significant part of the story of the Catholic Church in the United States. Today, the Diocese of St. Augustine encompasses 17 counties spanning the northeast section of Florida from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Ocean. It covers 11,032 square miles and serves about 171,000 registered Catholics. Church Statistics for the Diocese of St. Augustine Catholics in Diocese 171,000 Diocesan High Schools 4 Population (17 counties) 1,966,314 Diocesan Elementary Schools 25 Priests in Diocese 148 Special Education Schools 1 Deacons in Diocese 61 Total Students 10,559 Brothers in Diocese 1 Students enrolled in Parishes 52 Religious Education Programs 9,478 Mission Churches 8 *Source: The 2010 Official Catholic Directory Former Bishops of the Diocese of St. -

The Neoclassical in Providence: Columns! Columns Everywhere!

The Neoclassical in Providence: Columns! Columns everywhere! By Rachel Griffith and Peter Hatch Introduction From our experiences in this class and in the everyday world, we have seen that the Greek column is one of the most important, and pervasive contributions of Ancient Greek architecture to the architecture that followed it. In fact, so many examples of columns modeled after the Greek style exist, that in just a short walk from the Pembroke campus down toward RISD, we were easily able to find not only multiple examples of columns that epitomize all three Greek orders, but also numerous examples of columns obviously inspired by Greek forms. This influence even shows up in some very unexpected places. We have organized this presentation by those three orders, and by how closely each example follows the conventions of the style it comes from. Doric Columns Features of the Doric Column Overall simplicity Frieze above, containing alternating metopes and triglyphs Capital consists of a square sitting atop a flaring round component Fluted shaft No base, column rests directly on the stylobate Pure Doric The modern example at right, from a house on Brown and Meeting, is a faithful representation of the Doric order columns The shape of the capital, fluted columns, and lack of a base are consistent with the Doric order The only major departure from this style is the lack of metopes and triglyphs above the columns Pure Doric Manning Hall, modeled on the temple of Diana-Propylea in Eleusis, is an excellent example of most all the features of the Doric order, on a very large and impressive scale This building features Doric order columns with the characteristic fluting, simple capital, and a frieze with metopes and triglyphs, guttae along the roofline, and a shallow- sloped triangular gable, called the pediment. -

History of Architecture

ART 21000: HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE Course Description: An introduction to the history of architecture of the Western World from the Stone Age to skyscrapers based on lectures, readings from the required texts, completion of the Architectural Vocabulary Project, and the study visit to Italy. Lectures and readings cover the historical development of architecture in the following topics: Stone Age, Egyptian & Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, Early Christian, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and the Modern Era to the present. Class Meetings: Tuesday & Thursday, 4-8pm Texts: Watkin & XanEdu Course Schedule: Mtg # Date Topics Readings 1 T 5/12 Stone Age, Egypt, Mesopotamia & Greece TBD 2 R 5/14 Rome TBD 3 T 5/19 Exam #1; Early Christian & Romanesque TBD 4 R 5/21 Romanesque & Gothic TBD 5 T 5/26 Exam #2 Renaissance TBD 6 R 5/28 Baroque TBD 7 T 6/2 Exam #3; 18th century & 19th century TBD 8 R 6/4 19th century TBD 9 T 6/9 20th century TBD 10 R 6/11 Exam #4; AVP.1 DUE; Walking Tour TBD 11 M-S 6/21- Study abroad to Italy 6/29 12 R 7/3 AVP.2 Due Homework Schedule: 10% of final grade. Homework will consist of writing 20 questions, answers, and citations on each topic based on the readings from Watkin and/or XanEdu. 5/19 HW 1 Stone Age, Egypt & Mesopotamia, Greek, and Roman 5/26 HW 2 Early Christian, Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic 6/2 HW 3 Renaissance & Baroque 6/11 HW 4 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries Grading: Homework (4) 10% Attendance (10) 10% Exams (4) 40% AVP. -

1 Classical Architectural Vocabulary

Classical Architectural Vocabulary The five classical orders The five orders pictured to the left follow a specific architectural hierarchy. The ascending orders, pictured left to right, are: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite. The Greeks only used the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian; the Romans added the ‘bookend’ orders of the Tuscan and Composite. In classical architecture the selected architectural order for a building defined not only the columns but also the overall proportions of a building in regards to height. Although most temples used only one order, it was not uncommon in Roman architecture to mix orders on a building. For example, the Colosseum has three stacked orders: Doric on the ground, Ionic on the second level and Corinthian on the upper level. column In classical architecture, a cylindrical support consisting of a base (except in Greek Doric), shaft, and capital. It is a post, pillar or strut that supports a load along its longitudinal axis. The Architecture of A. Palladio in Four Books, Leoni (London) 1742, Book 1, plate 8. Doric order Ionic order Corinthian order The oldest and simplest of the five The classical order originated by the The slenderest and most ornate of the classical orders, developed in Greece in Ionian Greeks, characterized by its capital three Greek orders, characterized by a bell- the 7th century B.C. and later imitated with large volutes (scrolls), a fascinated shaped capital with volutes and two rows by the Romans. The Roman Doric is entablature, continuous frieze, usually of acanthus leaves, and with an elaborate characterized by sturdy proportions, a dentils in the cornice, and by its elegant cornice.