Crime Among Several Key Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Bain Lauchs Omcg 00A Fmt Cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page Ii Bain Lauchs Omcg 00A Fmt Cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page Iii

bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page i Understanding the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page ii bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page iii Understanding the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs International Perspectives Edited by Andy Bain Mark Lauchs Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page iv Copyright © 2017 Carolina Academic Press, LLC All Rights Reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bain, Andy, 1971- editor. | Lauchs, Mark, editor. Title: Understanding the outlaw motorcycle gangs : international perspectives / edited by Andy Bain and Mark Lauchs. Description: Durham, North Carolina : Carolina Academic Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016036256 | ISBN 9781611638288 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Motorcycle gangs. Classification: LCC HV6437 .U53 2016 | DDC 364.106/6--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036256 e-ISBN 978-1-53100-000-4 Carolina Academic Press, LLC 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page v For Aly, Mikey, Corrie & Ryan with Love Daddy To friends and family Mark bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page vi bain lauchs omcg 00a fmt cx2 12/12/16 3:55 PM Page vii Contents Illustrations xi Foreword xiii Scott Decker References xviii Acknowledgments xxi Notes on -

Overview Report

Overview Report Australian Multicultural Foundation Ethnic Youth Gangs in Australia Do They Exist? Overview Report by Rob White Santina Perrone Carmel Guerra Rosario Lampugnani 1999 i Ethnic Youth Gangs in Australia – Do They Exist? Acknowledgements We are grateful to the young people who took time to speak with us about their lives, opinions and circumstances. Their participation ought to be an essential part of any research of this nature. Particular thanks goes to John Byrne, Yadel Kaymakci, Gengiz Kaya, Katrina Bottomley, Peter Paa’Paa’, Mulki Kamil, Maria Plenzich, Marcela Nunez, and Megan Aumair for making contact with the young people, and for undertaking the interviews. The Criminology Department at the University of Melbourne hosted the research project, and we are most appreciative of the staff support, office space and resources provided by the Department. We wish to acknowledge as well the assistance provided by Anita Harris in the early stages of the project. Thanks are due to the Australian Multicultural Foundation for financial support, information and advice, and for ensuring that the project was able to continue to completion. We are also grateful to the National Police Ethnic Advisory Bureau for financial support. About the Authors Rob White is an Associate Professor in Sociology/Law at the University of Tasmania (on secondment from Criminology at the University of Melbourne). He has written extensively in the areas of youth studies, criminology and social policy. Santina Perrone is a Research Analyst with the Australian Institute of Criminology where she is currently working in the areas of workplace violence, and crime against business. -

U.S. Gangs: Their Changing History and Contemporary Solutions

Youth Gangs: U.S. Gangs: Their Changing History Members, Activities, and Measures and Contemporary to Decrease Violence Associated with Gangs Solutions by Carissa Pappas The purpose of this paper and the accompa- nying sidebars is to educate the public and youth-serving agencies about youth gangs–a phenomenon spreading around the world that negatively impacts youth and the communi- ties where they live. This paper discusses why youth join gangs, provides some demograph- ics of contemporary gangs, describes societal factors that influence violent gang activity in the United States and abroad, and describes Introduction several community-based gang intervention The good news is that overall U.S. juvenile programs. A case study on gang activity in El crime rates are down from the late 1980s and early Salvador is included. 1990s. Also, the number of youth gang members and Contributing author Carissa Pappas is a gradu- the total number of gangs are down. But the bad news ate student in sociology at George Washington is that gang members commit a disproportionately University in Washington, DC. Margot high number of the offenses committed by juveniles, Lowenstein is pursuing her bachelor’s degree including violent offenses. Given these findings, gang in psychology at the University of Pennsylva- prevention and intervention programs remain vitally nia in Philadelphia, PA. Nicole Poland is a re- important for at-risk youth and their communities. cent graduate of Colby College in Watersville, The existence of youth gangs in the United Maine. States -

Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs and Organized Crime

Klaus von Lampe and Arjan Blokland Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs and Organized Crime ABSTRACT Outlaw motorcycle clubs have spread across the globe. Their members have been associated with serious crime, and law enforcement often perceives them to be a form of organized crime. Outlaw bikers are disproportionately engaged in crime, but the role of the club itself in these crimes remains unclear. Three scenarios describe possible relations between clubs and the crimes of their members. In the “bad apple” scenario, members individually engage in crime; club membership may offer advantages in enabling and facilitating offending. In the “club within a club” scenario, members engage in crimes separate from the club, but because of the number of members involved, including high-ranking members, the club itself appears to be taking part. The club can be said to function as a criminal organization only when the formal organizational chain of command takes part in organization of the crime, lower level members regard senior members’ leadership in the crime as legitimate, and the crime is generally understood as “club business.” All three scenarios may play out simultaneously within one club with regard to different crimes. Fact and fiction interweave concerning the origins, evolution, and prac- tices of outlaw motorcycle clubs. What Mario Puzo’s (1969) acclaimed novel The Godfather and Francis Ford Coppola’s follow-up film trilogy did for public and mafiosi perceptions of the mafia, Hunter S. Thompson’s Electronically published June 3, 2020 Klaus von Lampe is professor of criminology at the Berlin School of Economics and Law. Arjan Blokland is professor of criminology and criminal justice at Leiden University, Obel Foundation visiting professor at Aalborg University, and senior researcher at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement. -

Police and Community Responses to Youth Gangs Rob White

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. TRENDS & ISSUES in crime and criminal justice A U S T R A L I A N I N S T I T U T E O F C R I M I N O L O G Y No. 274 March 2004 Police and Community Responses to Youth Gangs Rob White Although there are no national data on youth gangs in Australia there is a perception that youth gangs are an emerging problem. -

"Hard-Hard-Solid! Life Histories of Samoans in Bloods Youth Gangs In

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. “Hard-Hard-Solid! Life Histories of Samoans in Bloods Youth Gangs in New Zealand." A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Work at Massey University, Albany, New Zealand. Moses Ma’alo Faleolo 2014 Abstract Although New Zealand is home to the largest Samoan population outside of Samoa, there have been few studies of Samoan youth in gangs in New Zealand. This study sought to establish why Samoan youth gangs have formed in New Zealand urban centres, and why some young Samoan males are attracted to these gangs. This study used Delinquency Theory to explore the reasons for Samoan youth gang formation, and Socialization Theory to explore both how the cultural and societal socialization of young Samoan males lead them to gangs as well as how socialization within gangs secures their commitment to high risk and potentially dangerous behaviour. Life histories were collected over an eighteen month period from 25 young Samoan males aged over sixteen years who were members of various Bloods gangs. Findings from studies of socialization experiences confirmed that various socio-cultural strains weaken controls and led people into gangs, where they are then ‘re- socialized’ by their new gang peers. These life histories revealed gang members’ reasons for both joining and for leaving gangs and the extent to which Samoan cultural values and practices shape gang values and practices. -

Anti Gang Laws in Australia

Number 5/December 2013 Anti-gang laws in Australia Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 2 2. Selected legislation ....................................................................................... 3 2.1 South Australia .......................................................................................... 3 2.2 New South Wales .................................................................................... 10 2.3 Queensland ............................................................................................. 25 2.4 Western Australia..................................................................................... 39 2.5 Victoria ..................................................................................................... 42 2.6 Northern Territory..................................................................................... 45 2.7 Tasmania ................................................................................................. 49 3. Selected cases ............................................................................................. 50 3.1 Judicial power and the institutional integrity of courts ............................ 50 3.2 Implied freedom of political communication ........................................... 51 3.3 Mandatory sentencing ........................................................................... 52 3.4 Recent Queensland cases ................................................................... -

Master Thesis

Bond University Faculty of Law MASTER THESIS ORGANISED CRIME IN THE 21ST CENTURY: ARE THE STATES EQUIPPED TO FACE THE GLOBAL CRIME THREAT? Frederic Libert Supervisor: Prof. John Farrar Student ID: 13041746 August 2010 - Semester 102 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my truthful gratitude to my supervisor, Professor John Farrar, whose guidance and support from the preliminary to the concluding level enabled me to develop an understanding of the subject. I wish to express my warm and sincere thanks to Nadine Mukeba Ntumba for her continued encouragement. I am indebted to my parents, Claude Nepper and Eric Libert, for their unconditional support. I owe many thanks to my friends Marco le Carolo and Jean-Claude. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 9 1. THE CONCEPT OF ORGANISED CRIME ................................................................................ 11 1.1. Understand the Threat Posed by OC ........................................................................................................ 11 1.2. Historical Perspectives on the Concept of Organised Crime .................................................................... -

Tapping the Pulse of Youth in Cosmopolitan South-Western and Western Sydney”

Final Report “Tapping the Pulse of Youth in Cosmopolitan South-Western and Western Sydney” A Research Project funded by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship By Professor Jock Collins (University of Technology Sydney), Associate Professor Carol Reid (University of Western Sydney), Dr Charlotte Fabiansson (Macquarie University) with Dr Louise Healey (Macquarie University) The Department of Immigration and Citizenship provides funding to organisations under the Diversity and Social Cohesion Program. The views expressed in this publication are those of the funded author, researcher or organisation and are not an endorsement by the Commonwealth of this publication and not an indication of the Commonwealth’s commitment to any particular course of action. CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary...........................................................................................2 1.2 Research Project.........................................................................................2 1.3 Aims of the Research Project………………………………………….....3 1.4 Methodology..............................................................................................4 1.5 Main Findings ............................................................................................4 2. Introduction......................................................................................................12 3. Literature Review.............................................................................................14 4. Methodology ...................................................................................................19 -

Territorial Gangs and Their Consequences for Humanitarian Players Olivier Bangerter* Dr

Volume 92 Number 878 June 2010 Territorial gangs and their consequences for humanitarian players Olivier Bangerter* Dr. Olivier Bangerter has been working for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) since 2001and has been the advisor for the dialogue with armed groups in the unit for relations with arms carriers since 2008.He is a graduate in theology of both Lausanne (masters) and Geneva (PhD) universities. Abstract Territorial gangs are among today’s main perpetrators of urban violence, affecting the lives of millions of other people. They try to gain control of a territory in which they then oversee all criminal activities and/or ‘protect’ the people. Such gangs are found to differing degrees on every continent, although those given the most media attention operate in Central America. The violence that they cause has a major impact on the population in general and on their members’ families, as well as on the members themselves. Humanitarian organizations may find themselves having to deal with territorial gangs in the course of their ‘normal’ activities in a gang’s area, but also when the humanitarian needs per se of people controlled by a gang justify action. This article looks at some courses of action that may be taken by humanitarian agencies in an environment of this nature: dialogue with the gangs (including how to create a degree of trust), education, services, and dialogue on fundamental issues. Such * The views expressed in this article reflect the author’s opinions and not necessarily those of the International Committee of the Red Cross. This article was written prior to the publication of the Small Arms Survey’s Yearbook 2010 on ‘Gangs, Groups and Guns’ (Cambridge University Press). -

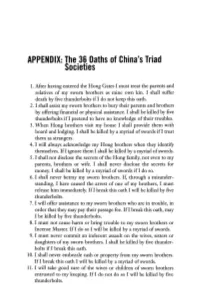

APPENDIX: the 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies

APPENDIX: The 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies 1. Mter having entered the Hong Gates I must treat the parents and relatives of my sworn brothers as mine own kin. I shall suffer death by five thunderbolts if I do not keep this oath. 2. I shall assist my sworn brothers to bury their parents and brothers by offering financial or physical assistance. I shall be killed by five thunderbolts if I pretend to have no knowledge of their troubles. 3. When Hong brothers visit my house I shall provide them with board and lodging. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I treat them as strangers. 4. I will always acknowledge my Hong brothers when they identify themselves. If I ignore them I shall be killed by a myriad of swords. 5. I shall not disclose the secrets of the Hong family, not even to my parents, brothers or wife. I shall never disclose the secrets for money. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I do so. 6. I shall never betray my sworn brothers. If, through a misunder standing, I have caused the arrest of one of my brothers, I must release him immediately. If I break this oath I will be killed by five thunderbolts. 7. I will offer assistance to my sworn brothers who are in trouble, in order that they may pay their passage fee. If I break this oath, may I be killed by five thunderbolts. 8. I must not cause harm or bring trouble to my sworn brothers or Incense Master. -

Review of Victorian Criminal Organisation Laws – Stage One Under Section 137 of the Criminal Organisations Control Act 2012 30 June 2020

Review of Victorian Criminal Organisation Laws – Stage One Under section 137 of the Criminal Organisations Control Act 2012 30 June 2020 Review of Victorian Criminal Organisation Laws Foreword Over the past decade, most States and Territories in Australia experimented with a new method of seeking to prevent and disrupt organised crime, which was expanding its reach into more and more legitimate activities. They did so by employing a scheme of declarations and control orders and unlawful association notices. Although couched in broad terms, these legislative initiatives were primarily prompted by the increasingly visible criminal activity of outlaw motorcycle gangs (OMCGs). Most, if not all, of these control statutes contained review provisions to determine if they were having their desired effect. Victoria’s Criminal Organisations Control Act 2012 (COCA) requires a review to be concluded by 30 June 2020. Many of the other reviews have been completed and we have benefited from the work which they have done. When we commenced this task, it was anticipated that we would consult with a wide range of stakeholders generally and conduct discussion roundtables with those whose work is central to disrupting organised crime, as well as those who engage with it more peripherally such as the regulators of certain industries and those who focus on the protection of human rights. However, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has precluded that interactive program of work and, accordingly, the Attorney-General has requested that we undertake the review in two stages. The first, to which this report relates, acquits the review obligations of the COCA.