Bogardus, George F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALEXANDER M. CARELL PATCH, JR. General, US Army, Retired SMA

ALEXANDER M. CARELL PATCH, JR. General, U.S. Army, Retired SMA Faculty 1920-1928 and 1932-1936 (1889 – 1945) Alexander M. “Sandy” Patch (23 November 1889 – 21 November 1945) was born on Fort Huachuca, a military post in Arizona where his father commanded a detachment. He never considered any career other than the army, and received his appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, NY, in 1909. He wanted to follow his father into the cavalry, but realizing that it was becoming obsolete, he instead chose the infantry, into which he was commissioned in 1913. In World War I, Patch served as an infantry officer and as an instructor in the Army's machine gun school. While he was commanding troops on the front line in France, his leadership came to the attention of George Marshall, then a member of General John J. Pershing's staff. General Patch was on the faculty of Staunton from 1920 -1928 as Professor of Military Science and then from 1932 – 1936 as Commandant of Cadets and Professor of Military Science. World War II During the buildup before the United States' entry into World War II, General Marshall was appointed Chief of Staff of the United States Army. He promoted Patch to brigadier general, and sent him to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to supervise the training of new soldiers there. Pacific Theater Patch was promoted to major general on 10 March 1942. In that year, he was sent to the Pacific Theater of Operations to organize the reinforcement and defense of New Caledonia. -

Kelley Hotel Ice Link Qr-Code

Stuttgart Lodging Table of Contents Section 1 – Guest Information Section 2 – Emergency Information Section 3 – Entertainment Section 4 – Telephone Directory Section 5 – Dining Options Section 6 – Local Information Stuttgart Lodging Dear Guest, I would like to take this opportunity to welcome you to Stuttgart Lodging. Whether your stay with us is for business or pleasure, it is our desire that your time in Stuttgart Lodging be comfortable and enjoyable. Our outstanding staff is available to answer your questions 24 hours a day. Simply press the “Front Desk” button on your room phone to be connected with a hotel staff member at any time. I am always looking for ways to improve guest services, and I find that the best resource for ideas are our guests. Accordingly, the QR- Codes and website URLs located on the reverse of this page will take you directly to the Hotels’ Interactive Customer Evaluation (ICE) site so that you can comment on our facility and services. Additionally, while you are at our front desk, please feel free to use one of the iPad tablets that are pre-set to the ICE website. Feel free to reach out to me at any time. I am usually available between the hours of 0730-1630, Monday through Friday and I am happy to schedule a meeting at any time. My telephone numbers are Civ. 07031-15-2079 or DSN 431-2079. Thank you for staying with us and we look forward to your next visit! Sincerely, C.A. Morris, CHA Manager, Stuttgart Army Lodging Stuttgart Lodging PANZER HOTEL ICE LINK QR-CODE Panzer Hotel ICE Comment Site Link: https://ice.disa.mil/index.cfm?fa=card&sp=121574&s=44&dep=*DoD KELLEY HOTEL ICE LINK QR-CODE Kelley Hotel ICE Comment Site Link: https://ice.disa.mil/index.cfm?fa=card&sp=1922&s=44&dep=*DoD Stuttgart Lodging Hours of Operation For your convenience and safety, the reception desk is staffed 24 hours daily. -

Retirees Appreciated, Supported at Garrison's 10Th Annual

Astronaut visits Explore the garrison schools Maginot Line Page 7 Page 12 -13 Vol. 46, No. 10, November 2017 Serving the Greater Stuttgart Military Community www.stuttgartcitizen.com Retirees appreciated, supported at garrison’s 10th annual RAD Story and photos by John Reese vision screenings, immunizations USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs and wellness/preventative health information. In a strong show of support to a “Getting immunized is very “purple” joint service community of important, so if you do end up getting retirees in the Stuttgart area, about sick, you won’t be as sick than if you two hundred participants used didn’t get it,” said Frances Barlock, services and garnered information nurse case manager, Patch Health at the U.S. Army Garrison Stuttgart’s Clinic. “The symptoms will be milder 10th annual Retiree Appreciation for you and it protects people who Day, Oct. 19. have COPD (chronic obstructive The event at the Swabian Special pulmonary disease), diabetes – and Events Center, Patch Barracks, its highly recommended for people featured multiple USAG Stuttgart over 50 to get their flu shots.” agencies together with federal and For retirees who missed RAD, service organizations sharing the Barlock recommends visiting the latest medical, financial and federal clinic 7:30 a.m. – 4 p.m., or coming benefit administrative supportfor one of the upcoming special services offered. ParticipantsSaturday vaccination days (see p.6 scheduled dental and medical for more). The tables in the Swabian Special Events Center buzz with activity at the 2017 exams, checked their blood “We’re trying to get everybody RAD, Oct. 19. -

The Department of France AMERICAN LEGION

The Department of France AMERICAN LEGION DEPARTMENT COMMANDER James Settle the Post Home. Make sure your delegates have a delegates letter or they will not be allowed to vote on any motions presented. My Fellow Legionaries It is time for Post Commanders and Adjutants to start I was invited to, and attended John Wayne Post GR79's ceremony working on their proposed Awards. The Awards packets are event on 11 January 2015, due to the Awards Chairman, Comrade Brown not later than honoring the 30th anniversary of 18 April 2015. the Awards Committee will meet on the 25th three soldiers' who died in a of April 2015 in Heilbronn. If your Awards packets are completed they can be turned in during the 3rd DEC in missile mishap on 11 January 1985, Kitzingen in March. at Red Leg Waldheide Heilbronn. The ceremony was done with respect and honored those fallen warriors of the COLD WAR. On 31st of January 2015 members of GR06, along with department officers conducted a membership drive at the Kaiserslautern Post GR01 will have a farewell dinner for Vice P.X on Panzer Kaserne from 1000 till 1700 hours. The Commander Stephen Ward, on the 2nd of February 2015. membership drive was a success, and GR06 even had a few Vice Commander Ward has been reassigned to the United of their current members renew for 2015. States, and will depart Germany on or about the 8th of Important information… February 2015. Vice Commander Ward will be sorely missed within the Department of France, we thank Vice The Department Sergeant-at-Arms/POW/MIA Chairman Commander Ward for his support to the Department of Comrade Hal Rittenberg(Post GR09)had to resign due to France over the last several years, and wish him and his health reasons. -

Stuttgart Dodea School Zones: SY 2019-2020

Stuttgart DoDEA School Zones: SY 2019-2020 March 2020 ALPHABETICALLY Primary towns are in bold-type or (parentheses) Town / City District ZipCode K-5 6-8 9-12 Special Notes: Aich (Aichtal) 72631 SES PMS SHS Aichtal 72631 SES PMS SHS Aidlingen 71134 SES PMS SHS (not Dachtel or Lehenweiler) Aldingen (Remseck/Neckar) 71686 RBES PMS SHS Altdorf (Kreis BB) 71155 SES PMS SHS (not Altdorf / Kreis ES) Asemwald (Stuttgart) 70599 RBES PMS SHS Asperg 71679 RBES PMS SHS Bad Cannstatt (Stgt) 70372 RBES PMS SHS 70374 Beihingen (Freiberg/Neckar) 71691 RBES PMS SHS Bergheim (Stuttgart) 70499 RBES PMS SHS Bernhausen (Filderstadt) 70794 PES PMS SHS Birkach (Stuttgart) 70599 RBES PMS SHS Böblingen 71032 SES PMS SHS 71034 Bonlanden (Filderstadt) 70794 PES PMS SHS Botnang (Stuttgart) 70195 PES PMS SHS Breitenstein (Weil/Schönbuch) 71093 SES BMS SHS Burgholzhof (Stuttgart) 70376 RBES PMS SHS Büsnau (Stuttgart) 70569 PES PMS SHS Dagersheim (Böblingen) 71034 SES PMS SHS Darmsheim (Sindelfingen) 71069 SES PMS SHS Dätzingen ((Grafenau) 71120 SES PMS SHS Degerloch (Stuttgart) 70597 RBES PMS SHS Denkendorf 73770 RBES PMS SHS Dettenhausen 72135 SES PMS SHS Deufringen (Aidlingen) 71134 SES PMS SHS Diezenhalde (Böblingen) 71034 SES PMS SHS Ditzingen 71254 RBES PMS SHS (not Heimerdingen or Schöckingen) Döffingen (Grafenau) 71120 SES PMS SHS Dürrlewang (Stuttgart) 70565 PES PMS SHS Echterdingen (L.E.) 70771 PES PMS SHS Eglosheim (Ludwigsburg) 71634 RBES PMS SHS Ehningen 71139 SES PMS SHS Eichholz (Sindelfingen) 71067 SES PMS SHS Eltingen (Leonberg) 71129 PES PMS SHS -

AFN Heidelberg Transitions to AFN Stuttgart Sgt

Vol. 41, No. 16 www.stuttgart.army.mil August 23, 2012 AFN Heidelberg transitions to AFN Stuttgart Sgt. Sarah Goss By Carola Meusel conducts a call-in radio USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs Office interview with a United Service Organizations- fter serving the Mannheim, Heidelberg Stuttgart representative and Stuttgart military communities for about upcoming Aalmost 20 years from Hammonds Bar- events during AFN racks in Seckenheim, then Coleman Barracks in Heidelberg’s morning Mannheim, the American Forces Network Heidelberg show Aug. 16 . On Aug. station is scheduled to move to Robinson Barracks in 18, AFN Heidelberg Stuttgart next year. transitioned to AFN It could be considered a reunion. Stuttgart, and the From 1959 until 1993, AFN was headquartered station, currently at Robinson Barracks on the first floor of Building located on Coleman 151, now home to the RB Fitness Center, Library and Barracks in Mannheim, other Family and MWR facilities. is scheduled to move “AFN Heidelberg looks forward to coming ‘home’ to USAG Stuttgart’s to Stuttgart, as AFN Stuttgart becomes operational on Robinson Barracks Robinson Barracks in the coming year,” said Lt. Col. next summer. Sherri Reed, AFN Europe commander. Lance Milsted See AFN transitions to Stuttgart on page 4 Ella Catchpole, 6, shakes hands with Brad Snyder, a Navy veteran and U.S. Paralympic Swimming Team More than 30 community members member during the C.A.R.E fair. The team will compete participate in a “flash mob” in front of in the 2012 London Paralympic Games. the Exchange during the C.A.R.E Fair. C.A.R.E. -

Stuttgart Students Head Back to School

Vol. 41, No. 17 www.stuttgart.army.mil September 6, 2012 Navy Lt. Brad Snyder, Stuttgart students head of the U.S. Paralympic swim team, back to school takes a break Patch Elementary during a School Principal training Nancy Hammack session Aug. (center) and 18 at the Assistant Sindelfingen Principal Sheree Badezentrum. Foster (far USAG left), introduce Stuttgart themselves and played host to go over school 34 swimmers rules with Aug. 16-27 students Aug. 27. before the team headed Susan Huseman to the 2012 Paralympic Games in London. Dag Kregenow Garrison supports U.S. swim team headed to London By Mark J. Howell disposal officer. “My friends and family USAG Stuttgart Public Affairs Office were there with a lot of love and sup- Mark J. Howell Susan Huseman port, and that helped a lot.” Eileen Dickinson (from left), sister Janice Venable, the school avy Lt. Brad Snyder may Nevertheless, he found himself do- Fallon and Saffron Dantzler head psychologist at Patch High School, have lost his sight after ing some soul searching. to class at Robinson Barracks assists junior Savannah Boyko in Nan improvised explosive “I asked myself, how can I continue Elementary/Middle School Aug. 27. deciphering her class schedule. device attack in Afghanistan last Sep- my relevance and success I had in the tember, but he hasn’t lost his vision Navy?” Snyder said. “The Paralympics Böblingen … a vision of himself atop a podium program was the perfect way to do that.” Elementary/Middle sporting Olympic gold. School second- Snyder, who grew up near the beach- After one bomb went off, Snyder es of Florida and was a member of the graders Jordan rushed to aid his comrades, and in the White (left) and Naval Academy swim team, has always process, stepped on another. -

WELCOME to STUTTGART Special PCS-In Edition

STUTTGART Vol. Vol. 47, 46, No.7, No. 7, Special August Edition2017 Serving Serving the Greater the Stuttgart Stuttgart Military Military Community Community Welcome www.stuttgartcitizen.com Edition 2018-2019 WELCOME TO STUTTGART Special PCS-In Edition YOU ARE HERE! Your home away from Eating and drinking like a What to know if you get Caring for your pet over- home, page 7 local, page 10 pulled over, page 19 seas, page 26 Page 2 WELCOME TO STUTTGART The Citizen, 2018-2019 Welcome to Stuttgart Where community members say, “I’m Glad I Live Here!” USAG Stuttgart Public A airs Criteria for Performance Excellence, Operations Command Africa, families. With this guide and the which focused on garrisons’ pro- Marine Forces Europe and Africa, assistance of a sponsor, the tran- The U.S. Army Garrison cesses for providing excel- and Defense Information sition overseas into this commu- Stuttgart welcomes incoming com- lence in facilities and Systems Agency nity will be met with a lot of excite- munity members to the best gar- services in sup- Europe are all ment and a little stress. This issue rison in the U.S. Army, as judged port of Soldiers, headquar- features information on housing, by the 2017 Army Communities of Civilians, and tered here. schools, medical and dental care, Excellence program. their families. Community and other aspects of life in the Stuttgart is a great place to Using these members Stuttgart military community. An work and live, with a dynamic joint bench- work with introduction to life on our instal- military community spread across marks, members lations and the surrounding local five installations. -

Authorities and Options for Funding USSOCOM Operations

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that ad- dress the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Authorities and Options for Funding USSOCOM Operations Elvira N. Loredo, John E. -

Welcome to Stuttgart Marriott Hotel Sindelfingen

WELCOME TO STUTTGART MARRIOTT HOTEL SINDELFINGEN PRE-ARRIVAL INFORMATION This booklet will provide you with some important information to help you prepare for your stay at the Stuttgart Marriott Hotel Sindelfingen, Sindelfingen and Stuttgart area. We look forward to meeting you upon your arrival! Stuttgart Marriott Hotel Sindelfingen Mahdentalstrasse 68, 71065 Sindelfingen, Germany [email protected] T +49 7031 696 0 www.stuttgart-marriott-sindelfingen.de Stuttgart Marriott Hotel Sindelfingen Mahdentalstrasse 68 71065 Sindelfingen Baden-Württemberg Germany For information about the hotel please contact the hotel directly: +49 7031 – 696 0 or stuttgart.marriott@marriott hotels.com For reservations please contact the reservation department directly: +49 7031 – 696 – 555 or reservation.sindelfingen@ marriott.com Earn Marriott Rewards Points during your long-term stay! Stuttgart Marriott Hotel Sindelfingen Mahdentalstrasse 68, 71065 Sindelfingen, Germany [email protected] T +49 7031 696 0 www.stuttgart-marriott-sindelfingen.de General information about public transportation Taxi: Please note that the United States Army Garrison Stuttgart is partnering with an authorized taxi service that is allowed to take you directly on base Please contact the Front Desk for further information Bus and Rail: You can acquire your bus ticket in the bus directly or at ticket machines at the bus stops o More information: http://www.vvs.de/ You can book train tickets online or acquire them at ticket machines at the -

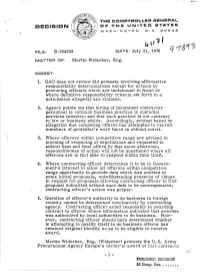

B-184328 Protest Involving Bidder Responsibility and Procurement

1,.L R THE COMPTROLLER GENERAL DECISION OF THE UNITED STATES WASH INGTO N. D. C. 20546 FILE: B-184328 DATE: July 21, 1976 q -ig MATTER OF: Martin Widerker, Eng. DIGEST: 1. GAO does not review bid protests involving affirmative responsibility determinations except for actions by procuring officials which are tantamount to fraud or where definitive responsibility criteria set forth in a solicitation allegedly are violated. 2. Agency points out that hiring of incumbent contractor personnel is common business practice in custodial services industry; and that such practice is not contrary to law or business ethics. Accordingly, protest based on allegation that competing offeror has attempted to recruit members of protester's work force is without merit. 3. Where offerors within competitive range are advised in morning of reopening of negotiations and requested to submit best and final offers by that same afternoon, reasonableness of action will not be questioned where all offerors are in fact able to respond within time limit. 4. Where contracting officer determines it to be in Govern- ment's interest to allow all offerors within competitive range opportunity to provide data which was omitted in some initial proposals, notwithstanding presence of clause in request for proposals allowing contracting officer to find proposal submitted without such data to be nonresponsive, contracting officer's action was proper. 5. Question of offeror's authority to do business in foreign country cannot be determined conclusively by contracting agency. Contracting officer acted reasonably in awarding contract to offeror where information indicated that awardee was authorized by local authorities to do business. -

“Exercise–Exercise–Exercise!”

Independence Run to Day celebrated Remember honors the fallen Page 3 Page 23 Vol. 47, No. 10, August 2018 Serving the Greater Stuttgart Military Community www.stuttgartcitizen.com “Exercise–exercise–exercise!” Photos by Carola Meusel, USAG Stuttgart Public A airs Stallion Shake 2018 tested garrison and host nation emergency responders’ reaction to an accidental release of a toxic gas in the cellar of the Kelley Club, July 21. See p. 12 for more photos and the story. At top, the incident scene in the midst of the rescue operation; left, fi refi ghters in chemical/bio hazard suits undergo decontamination; right, emergency vehicles from the City of Stuttgart and USAG Stuttgart arrive at Kelley Barracks. CARE Fair, warehouse sale, fl ea market and more coming Sept. 8 Army Community Service information about garrison services. USAG Stuttgart Family & Morale, It’s a great way to connect with the Welfare and Recreation many organizations of the USAG Stuttgart community. e annual Community e coordination of the 2018 Activities, Registration, & Education CARE Fair is assigned to USAG “CARE Fair” coming up on Sept. 8, Stuttgart Family & Morale, Welfare 10 a.m.–2 p.m., in the Panzer Main and Recreation’s team is commit- Exchange mall. ted to hosting a fantastic event e fair is a much-awaited op- along the lines of what partici- Photo by Holly DeCarlo-White, USAG Stuttgart Public A airs portunity for community members pants have become used to over Representatives of numerous garrison organizations prepare to inform and to sign up for activities and clubs, the years.