Medieval Churches Walk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excursions 2012

SIAH 2013 010 Bu A SIAH 2012 00 Bu A 31 1 1 10 20 12 127 EXCURSIONS 2012 Report and notes on some findings 21 April. Clive Paine and Edward Martin Eye church and castle Eye, Church of St Peter and St Paul (Clive Paine) (by kind permission of Fr Andrew Mitchell). A church dedicated to St Peter was recorded at Eye in 1066. The church was endowed with 240 acres of glebe land, a sure indication that this was a pre-Conquest minster church, with several clergy serving a wide area around Eye. The elliptical shaped churchyard also suggests an Anglo-Saxon origin. Robert Malet, lord of the extensive Honour of Eye, whose father William had built a castle here by 1071, founded a Benedictine priory c. 1087, also dedicated to St Peter, as part of the minster church. It seems that c. 1100–5 the priory was re-established further to the east, at the present misnamed Abbey Farm. It is probable that at the same time the parish church became St Peter and St Paul to distinguish itself from the priory. The oldest surviving piece of the structure is the splendid early thirteenth-century south doorway with round columns, capitals with stiff-leaf foliage, and dog-tooth carving around the arch. The doorway was reused in the later rebuilding of the church, a solitary surviving indication of the high-status embellishment of the early building. The mid fourteenth-century rebuilding was undertaken by the Ufford family of Parham, earls of Suffolk, who were lords of the Honour of Eye 1337–82. -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

Pre-Industrial Mines and Quarries

Pre-industrial Mines and Quarries On 1st April 2015 the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England changed its common name from English Heritage to Historic England. We are now re-branding all our documents. Although this document refers to English Heritage, it is still the Commission's current advice and guidance and will in due course be re-branded as Historic England. Please see our website for up to date contact information, and further advice. We welcome feedback to help improve this document, which will be periodically revised. Please email comments to [email protected] We are the government's expert advisory service for England's historic environment. We give constructive advice to local authorities, owners and the public. We champion historic places helping people to understand, value and care for them, now and for the future. HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice Introductions to Heritage Assets Pre-industrial Mines and Quarries May 2011 Fig. 1. An aerial view of the Late Neolithic flint mines at Grime’s Graves, Norfolk. Each hollow represents the location of a former mine or pit, and mounded up between them lie the spoil dumps of chalk which came from the shafts and galleries. INTRODUCTION People have mined and quarried stone and minerals recognisable, types of stone from culturally important for many thousands of years for a wide range of uses sources that created a value to the community. from crafting tools to producing building stone. The Artefacts crafted from these raw materials were then earliest extraction sites are now known to be some used in important ceremonies, and some were found of the first archaeological monuments to appear in buried in pits. -

Winchester Stone by Dr John Parker (PDF)

Winchester Stone by John Parker ©2016 Dr John Parker studied geology at Birmingham and Cambridge universities. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of London. For over 30 years he worked as an exploration geologist for Shell around the world. He has lived in Winchester since 1987. On retirement he trained to be a Cathedral guide. The Building of Winchester Cathedral – model in the Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux 1 Contents Introduction page 3 Geological background 5 Summary of the stratigraphic succession 8 Building in Winchester Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon periods 11 Early medieval period (1066-1350) 12 Later medieval period (1350-1525) 18 16th to 18th century 23 19th to 21st century 24 Principal stone types 28 Chalk, clunch and flint 29 Oolite 30 Quarr 31 Caen 33 Purbeck 34 Beer 35 Upper Greensand 36 Portland 38 Other stones 40 Weldon 40 Chilmark 41 Doulting 41 French limestones 42 Coade Stone 42 Decorative stones, paving and monuments 43 Tournai Marble 43 Ledger stones and paving 44 Alabaster 45 Jerusalem stone 45 Choice of stone 46 Quarries 47 A personal postscript 48 Bibliography and References 50 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Photographs and diagrams are by the author, unless otherwise indicated 2 Introduction Winchester lies in an area virtually devoid of building stone. The city is on the southern edge of the South Downs, a pronounced upland area extending from Salisbury Plain in the west to Beachy Head in the east (Figs. 1 & 2). The bedrock of the Downs is the Upper Cretaceous Chalk (Fig. 3), a soft friable limestone unsuited for major building work, despite forming impressive cliffs along the Sussex coast to the east of Brighton. -

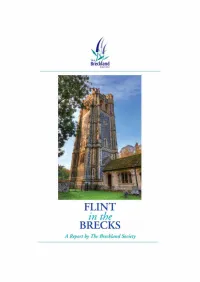

Flint in the Brecks WEB ONLY

©Text, layout and use of all images in this publication: The Breckland Society 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Text written by Anne Mason & James Parry. Editing by Liz Dittner. Front cover: The Church of St Andrew & St Patrick, Elveden. © Nick Ford. Designed by Duncan McLintock. Printed by SPC Printers Ltd, Thetford. Project trainees at one of the flintknapping workshops led by John Lord in November 2014. This report is dedicated to the memory of Dr Colin Pendleton (1952–2014), Senior Historic Environment Records Officer at Suffolk County Council, who shared his enthusiasm, knowledge and expertise so generously with the Breckland Society on this and other projects. FLINT IN THE BRECKS Contents Map of the Brecks . 4 Introduction . 5 1. Context and Background . 7 2. Flint in the Built Heritage of the Brecks . 10 3. The Gunflint Industry in the Brecks . 20 4. Social History and Legacy . 27 Appendix One: The Frank Norgate Diaries . 36 Appendix Two: The William Carter Flint Mosaics . 38 Bibliography and Credits . 40 A REPORT BY THE BRECKLAND SOCIETY FLINT IN THE BRECKS 4 A REPORT BY THE BRECKLAND SOCIETY FLINT IN THE BRECKS Introduction The Breckland Society was set up in 2003 to encourage interest and research into the natural, built and social heritage of the East Anglian Brecks. It is a membership organisation working to help protect the area and offering a range of activities to those who wish to see its special qualities preserved and enhanced. -

Two Exceptional Tudor Houses in Hitcham: Brick

TWO EXCEPTIONAL TUDOR HOUSES IN HITCHAM: BRICK HOUSE FARM AND WETHERDEN HALL by EDWARD MARTIN HITCHAM LIES IN the clay country of central Suffolk, a large sprawling parish with many dispersed farmsteads. To the casual visitor there would appear to he little particularly notable about these farmhouses, for, as is often the casc in Suffolk, the houses do not openly declare their age or distinction. The two houses examined here are very different, but in both cases aspects of their architecture and history suggest that they arc probably unique structures. BRICK HOUSE FARM Description In 1925 the Revd Edmund Farrer of Botesdale noted that 'There is undoubtedly somcthing in the history connected with Brick House Farm which sets it, as it were, apart from other farmhouses in Suffolk' (Farrer 1925). Farrer, an observant antiquarian with a keen interest in Suffolk's architectural heritage, had been prompted to visit the place after seeing a brief reference to it in an article by the Revd Henry Copinger Hill (Hill 1924). Hill, who was the rector of a neighbouring parish to Hitcham, was mainly concerned with the Roman site that lay on the farm; it therefore- fell to Farrer to make the first description of the farmhouse. Like all subsequent visitors, Farrer was struck by the incongruity between the small size of the house and the apparent wealth displayed in its brick corner turrets and the knapped flint decoration. Farrer was percipient enough to see that the house could never have been much larger than it was when he saw it, noting that its cramped site left little room for any extension or wing. -

The Parish Church of St Peter and St Paul, Brockdish

The Parish Church of St Peter and St Paul, Brockdish. SOME LANDMARKS IN THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH Our church is not a large church, nor particularly grand. It was renewed and restored in Victorian times and has sometimes been the object of sniffy architectural snobbery by 20th century writers who preferred older, medieval churches. Or it was ignored completely by authors singing the splendours of a county overflowing with glorious churches. Possibly this is because our church has always been off the beaten track, standing remote from the main village down a country lane. But it is the oldest building in the village, at least nine hundred years old and has a wealth of interesting details from across the centuries. The medieval church was restored and renovated in Gothic revival style in the mid-19th century by the remarkable Rector, Reverend George France, whose ambitious commitment to beautify the building leaves a legacy now much prized by experts in Victorian architecture and decoration. The Parish Church of Saint Peter and St Paul, Brockdish, Norfolk Adherence to the formal worship of Christianity has waxed and waned over the centuries and from the time of the Reformation in the mid-16th century, the people of Norfolk have been divided in their attachment to the established church. What we see today is a building that reflects the changes in religious observance and faith but is still a fundamental part of 1 our village identity, even when there aren’t often many people in it! The parish church belongs to all of us, including those who stop by out of curiosity and we hope this little guide will illustrate how a small medieval church became a splendid Victorian one. -

The Hammer-Beam Roof: Tradition, Innovation and the Carpenter’S Art in Late Medieval England

The Hammer-Beam Roof: Tradition, Innovation and the Carpenter’s Art in Late Medieval England Robert Beech A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is about late medieval carpenters, their techniques and their art, and about the structure that became the fusion of their technical virtuosity and artistic creativity: the hammer-beam roof. The structural nature and origin of the hammer-beam roof is discussed, and it is argued that, although invented in the late thirteenth century, during the fourteenth century the hammer-beam roof became a developmental dead-end. In the early fifteenth century the hammer-beam roof suddenly blossomed into hundreds of structures of great technical proficiency and aesthetic acumen. The thesis assesses the role of the hammer-beam roof of Westminster Hall as the catalyst to such renewed enthusiasm. This structure is analysed and discussed in detail. -

Addenda to Decoding Flint Flushwork John Blatchly

347 ADDENDA TO DECODING FLINT FLUSHWORK compiled by JOHN BLATCHLYand THE LATEPETER NORTHEAST SINCE THE BOOK was published by this Institute in 2005 it has sold out and inevitably several new examples of devices have been discovered. Kerstin Fletcher made the interesting general suggestion that the AlOdevice should properly belAll because the orb, in the medieval mind, stood for All. The rebus of Bishop John Alcock on his chantrv at Ely has an eagle of St John (or a cockerel) sitting on an orb, as on brass lecterns of the period. Walberswick St Andrew, Suffolk The most significant discovery is of a type of flushwork with devices which is a precursor of the work of the Aldryche and Woodrofe workshops. It is only to be found on the east wall of the small church built re-employing original materials in the ruins of the larger church of St Andrew at Walberswick. Here Richard Russell of Dunwich and Adam Powle of Blvthburgh were engaged to build the tower under a contract dated 1426. In his book on Suffolk arcades, Birkin Haward suggests that this tower was the earliest church commission undertaken by these masons on the north-east Suffolk coast.= Unfortunately nothing comparable has been found on the exterior walls of the other churches whose arcades he suggests they built at Blythburgh, Kessingland, Southwold, Woodbridge and Wangford. • FIG. 98 - The plMth of the eastI wa.. o. tne smaller church built within the rums at Walberswick, with (inset) the 'Andrew' device enlarged. 348 JOHN BLATCHLY and PETER NORTHEAST There is an Andrew saltire in flushwork set in a lozengy panel on the chancel east wall of the reduced church, with ambiguously formed devices in the upper and lower triangles which could spell a pair of Rs for Richard Russell, As for Andrew or F-Ns for Mary. -

P Gloss.1713

GLOSSARY Abbreviations Agora. The Greek equivalent of the Roman forum, a place of open-air assembly or market. (Isl) refers mainly to Islamic buildings. (Bud) refers Aisles. Lateral divisions parallel with the nave in a mainly to Buddhist buildings. (Hind) refers mainly to basilica or church. Hindu buildings. Terms relating specifically to Jap- Alabaster. A very white, fine-grained, translucent, anese architecture and construction are explained gypseous mineral, used to a small extent as a building within the relevant chapters. material in the ancient Middle East, Greece, Rome the Eastern Empire of Byzantium and, nearer to our Abacus. A slab forming the crowning member of a own day, by certain Victorian architects for its capital. In Greek Doric, square without chamfer or decorative qualities (and biblical associations). In moulding. In Greek Ionic, thinner with ovolo mould- Italy a technique was evolved many centuries ago ing only. In Roman Ionic and Corinthian, the sides are (and still survives) of treating alabaster to simulate hollowed on plan and have the angles cut off. In marble while there seems little doubt that in the past Romanesque, the abacus is deeper but projects less marble was often mistakenly described as alabaster. and is moulded with rounds and hollows, or merely Alae. Small side extensions, alcoves or recesses chamfered on the lower edge. In Gothic, the circular opening from the atrium (or peristyle) of a Roman or octagonal abacus was favoured in England, while house. the square or octagonal abacus is a French feature. Alpa vimana (Hind). Basic form of shrine in south Ablaq (Isl). -

Religion and Place in Leeds

Religion and Place in Leeds Religion and Place in Leeds John Minnis with Trevor Mitchell Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ www. english-heritage. org.uk English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. © English Heritage 2007 Printing 10 987654321 Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage or © Crown copyright. NMR. First published 2007 ISBN 978-1-905624-48-5 Product code 51337 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Front cover The east end of All rights reserved Headingley St Columba United No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or Reformed Church (1966, W & A mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Tocher), one of the most striking permission in writing from the publisher. nonconformist churches of the period, is reminiscent of the prow of a great battleship. [DP027104] Application for the reproduction of images should be made to the National Monuments Record. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and we apologise in advance for any unintentional Inside front cover The Greek Orthodox omissions, which we would be pleased to correct in any subsequent edition of this book. Church of the Three Hierarchs has successfully adapted the former Harehills Primitive Methodist Chapel (1902, The National Monuments Record is the public archive of English Heritage. For more information, W Hugill Dinsley) for a new use, contact NMR Enquiry and Research Services, National Monuments Record Centre, Kemble Drive, adding the iconostasis seen here as the Swindon SN2 2GZ; telephone (01793) 414600. -

The Major New BBC1 Series – 'How We Built Britain' Looks at the History of the Country Through Our Buildings

How we Built Britain The BBC1 series – ‘How we Built Britain’ (shown Summer 2007) looked at the history of the country through our buildings. The first programme featured the East of England region – which abounds in outstanding examples of architecture. From Britain’s greatest collection of cathedrals to the award-winning terminal at Stansted Airport. Discover flint and timber buildings, and stately homes dating from Tudor to Victorian times. Over the next few pages we have listed a selection of key places to visit - check out our web site at www.visiteastofengland.com for opening times and admission prices. Architecture of the Region Building stone is virtually non-existent in the East of England, apart from a few special areas: z Barnack (Cambridgeshire) - the famous limestone here was worked from Roman times to the end of the 15th C. Ely and Peterborough Cathedrals are good examples of the stone in use. z Carstone (West Norfolk) - this dark brown stone forms a ridge between Castle Rising and Heacham. It has been widely used in the area as a building stone, and Downham Market was once known as the "Gingerbread town". z Puddingstone (Hertfordshire) - this unusual stone is made up of rounded Flint villages flint pebbles. A large piece sits opposite the church in the village of Standon. It has been used for building walls. z Sandstone - The Greensand Ridge runs from Leighton Buzzard in Bedfordshire to Gamlingay in Cambridgeshire. In some places, ‘glauconite’ (an iron-bearing mineral) colours the stone an amazing green - the origin of the name ‘Greensand’. Today you can see it used in local villages, churches, walls and bridges.