An Interview with Wilf Prigmore Julia Round Writer and Editor Wilf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

De Maria a Madalena Representações Femininas Nas Histórias Em Quadrinhos

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES EDILIANE DE OLIVEIRA BOFF De Maria a Madalena representações femininas nas histórias em quadrinhos São Paulo 2014 EDILIANE DE OLIVEIRA BOFF De Maria a Madalena: representações femininas nas histórias em quadrinhos Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Comunicação da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora em Ciências da Comunicação Área de Concentração: Interfaces Sociais da Comunicação Orientador: Prof. Dr. Waldomiro de Castro Santos Vergueiro São Paulo 2014 2 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. BOFF, E.O. De Maria a Madalena: representações femininas nas histórias em quadrinhos Tese apresentada à Faculdade de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Doutora em Comunicação. Aprovado em: Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr. ________________________ Instituição: _________________________ Julgamento: ______________________ Assinatura: ________________________ Prof. Dr. ________________________ Instituição: _________________________ Julgamento: ______________________ Assinatura: ________________________ Prof. Dr. ________________________ Instituição: _________________________ Julgamento: ______________________ Assinatura: ________________________ Prof. Dr. ________________________ Instituição: _________________________ Julgamento: -

Schoolgirls' Own Library

The Schoolgirl’s Own Library 1922-1940 The School Friend, School Girl and Schoolgirls’ Own featured a range of self-contained stories, serials and articles each week, in addition to the main attraction. A large number of these additional stories were also reprinted in the SOL. The Schoolgirls Own Library Index 2 - 1922 - No. Title Author School Source 1 The Schoolgirl Outcast Anon (J G Jones) 2 The Rockcliffe Rebels Anon - 1923 - 3 Adopted by the School Louise Essex [LI] 4 The Mystery Girl of Morcove Marjorie Stanton [ELR] Morcove 5 Castaway Jess Julia Storm [GGF] Schoolgirls’ Own 1921 6 The Schemers in the School Hilda Richards [JWW] Cliff House 7 The Minstrel Girl Anon (ELR) School Friend 1921 8 Delia of the Circus Marjorie Stanton [HP] Morcove 9 The Girl Who Chose Riches Joy Phillips School Friend 1921 10 Joan Havilland’s Silence Joy Phillips School Friend 1922 11 The Guides of the Poppy Patrol Mildred Gordon Schoolgirls’ Own 1921 12 Their Princess Chum Hilda Richards [JWW] Cliff House 13 In Search of Her Father Joan Vincent [RSK] School Friend 1921 14 The Signalman’s Daughter Gertrude Nelson [JWB] School Friend 1922 15 The Little Mother Mildred Gordon Schoolgirls’ Own 1922 16 The Girl Who Was Spoilt Mildred Gordon Schoolgirls’ Own 1921 17 Friendship Forbidden Ida Melbourne [ELR] School Friend 1922 18 The Schoolgirl Queen Ida Melbourne [ELR] School Friend 1922 19 From Circus to Mansion Adrian Home Schoolgirls’ Own 1921 20 The Fisherman’s Daughter Mildred Gordon Schoolgirls’ Own 1921 21 The Island Feud Gertrude Nelson [JWB] Schoolgirls’ -

An Annual Treat!

Scottish Memories An annual treat! Young people might be more interested in the virtual worlds of their video games these days, and many toys and comics have been long forgotten, but there’s one stocking-filler stalwart that remains a popular present for young and old – the annual oday millions of annuals are has passed, whereas an annual with purchased each Christmas, a non-Xmas themed cover is likely covering subjects as varied to sell into January and February. as Dr Who, Blue Peter Some of the covers extended from the T and the Brownies, with front to the rear cover and are very youngsters thrilled to receive a fun, appealing to the eye – Beano from the hardback book that is intended to be mid 1950s spring to mind.’ enjoyed throughout the coming year. Inside the annuals, readers were, Take a look at most kids’ bookshelves and still are, treated to a mix of longer and you’ll no doubt see the uniform stories, jokes, puzzles, and, perhaps spines of a favourite annual… if only most importantly to today’s annual we older, supposedly wiser folk had kept collectors, wonderful, bright artwork, our Broons, Beano and Buster annuals bringing together the readers’ favourite from all those years ago, we could be sat characters and subjects in one title. on a goldmine. According to collector- Perhaps you remember receiving turned-comic-and-annual-auctioneer Phil copies of the Rupert Bear annual each Shrimpton, many old annuals are now year, with the beautifully drawn strips worth hundreds of pounds. ‘The first giving the reader the choice of enjoying Broons and Oor Wullie annuals from a quick version or a more in-depth story. -

Reading Production and Culture UK Teen Girl Comics from 1955 to 1960

Ormrod, J (2018) Reading production and culture UK teen Girl comics from 1955 to 1960. Girlhood Studies, 11 (3). pp. 8-33. ISSN 1938-8209 Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/622860/ Version: Accepted Version Publisher: Berghahn DOI: https://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2018.110304 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Reading Production and Culture in UK Teen Girl Comics 1955 to 1960 Joan Ormrod Abstract In this article I explore the production of teen girl comics such as Marilyn, Mirabelle, Roxy and Valentine in the promotion of pop music and pop stars from 1955 to 1960. These comics developed alongside early pop music and consisted of serial and self-contained picture stories, beauty and pop music articles, advice columns, and horoscopes. Materiality is a key component of the importance of comics in the promotional culture in a media landscape in which pop music was difficult to access for teenage girls. I analyze the comics within their historical and cultural framework and show how early British pop stars were constructed through paradoxical discourses such as religion, consumerism, and national identity to make them safe for teen girl consumption. The promotion of these star images formed the foundation for later pop music promotion and girl fan practices. Keywords consumerism, fandom, fantasy, materiality, pop music, promotion, stardom, teen magazines Introduction Teen girl comics appeared in the mid-1950s, a pivotal moment in popular culture when the teenage girl was identified as a member of a potentially lucrative market, and American culture began to pervade British teenage music, fashion, and attitudes. -

Kirby Letterhead

SUPERGIRL IN THE BRONZE AGE! October 2015 No.84 $ 8 . 9 5 Supergirl TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 Pre-Crisis Supergirl I Death of Supergirl I Rebirths of Supergirl I Superwoman ALAN BRENNERT interview I HELEN SLATER Supergirl movie & more super-stuff! 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, Number 84 October 2015 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow TM DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Karl Heitmueller, Jr., with Stephen DeStefano Bob Fingerman Dean Haspiel Kristen McCabe Jon Morris Jackson Publick COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER John Morrow SPECIAL THANKS Cary Bates Elliot S. Maggin Alan Brennert Andy Mangels ByrneRobotics.com Franck Martini BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Glen Cadigan Jerry Ordway FLASHBACK: Supergirl in Bronze . .3 and The Legion George Pérez The Maid of Might in the ’70s and ’80s Companion Ilya Salkind Shaun Clancy Anthony Snyder PRINCE STREET NEWS: The Sartorial Story of the Sundry Supergirls . .24 Gary Colabuono Roger Stern Oh, what to wear, what to wear? Fred Danvers Jeannot Szwarc DC Comics Steven Thompson THE TOY BOX: Material (Super) Girl: Pre-Crisis Supergirl Merchandise . .26 Jim Ford Jim Tyler Dust off some shelf space, ’cause you’re gonna want this stuff Chris Franklin Orlando Watkins FLASHBACK: Who is Superwoman? . .31 Grand Comics John Wells Database Marv Wolfman Elliot Maggin’s Miracle Monday heroine, Kristen Wells Robert Greenberger BACKSTAGE PASS: Adventure Runs in the Family: The Saga of the Supergirl Movie . .35 Karl Heitmueller, Jr. Hollywood’s Ilya Salkind and Jeannot Szwarc take us behind the scenes Heritage Comics Auctions FLASHBACK: Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 . -

A M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S the by JOHN WELLS 1960-1964

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1960-1964 byby JOHN JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chroncles ........ 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data......................................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowlegments................................. 6 Chapter One: 1960 Pride and Prejudice ................................................................... 8 Chapter Two: 1961 The Shape of Things to Come ..................................................40 Chapter Three: 1962 Gains and Losses .....................................................................74 Chapter Four: 1963 Triumph and Tragedy ...........................................................114 Chapter Five: 1964 Don’t Get Comfortable ..........................................................160 Works Cited ......................................................................214 Index ..................................................................................220 Notes Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles The monthly date that appears on a comic book head as most Direct Market-exclusive publishers cover doesn’t usually indicate the exact month chose not to put cover dates on their comic books the comic book arrived at the newsstand or at the while some put cover dates that matched the comic book store. Since their inception, American issue’s release date. periodical publishers—including but not limited to comic book publishers—postdated -

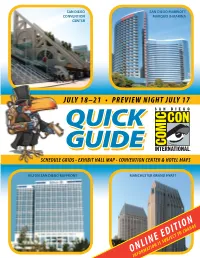

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

Captain Britain: Lion and the Spider Vol. 3 Free

FREE CAPTAIN BRITAIN: LION AND THE SPIDER VOL. 3 PDF Chris Claremont,John Byrne,Brian K. Vaughan,Steve Parkhouse | 199 pages | 26 Mar 2009 | Panini Publishing Ltd | 9781846534010 | English | Tunbridge Wells, United Kingdom Captain Britain US & UK collections Series by Alan Moore Captain Britain by Alan Moore. The entire saga of Britain's costumed protector is… More. Want to Read. Shelving menu. Shelve Captain Britain. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Rate it:. Reprints stories from Mighty World of Marvel, illu… More. Shelve Captain Britain: Legacy of a Legend. Book US 1. Shelve Captain Britain: Birth of a Legend. Book US Captain Britain: Lion and the Spider Vol. 3. The adventures of Marvel U. Shelve Captain Britain: Siege of Camelot. Book US 3. Captain Britain Omnibus by Alan Moore. One of the Marvel Universe's most staggering sagas… More. Shelve Captain Britain Omnibus. Book UK 1. This is the first in a series of Captain Britain T… More. Book UK 2. This is the second in the series of Captain Britai… More. Book UK 3. This is the third volume in the series of Captain … More. Book UK 4. This is the fourth in the series of Captain Britai… More. Book UK 5. This is the fifth in the series of Captain Britain… More. Shelve Captain Britain: End Game. Book Captain Britain: Lion and the Spider Vol. 3 1. Captain Britain and MI13, Vol. Secret Invasion hits the U. Book MI13 2. Book MI13 3. The king of the vampires is back As if the hoards … More. Captain Britain by Chris Claremont. -

Annual Report 2015

CELEBRATING 25 YEARS harn.ufl.edu DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE IN THIS 25TH YEAR OF THE HARN’S SHORT BUT EVENTFUL HISTORY THERE HAS BEEN MUCH CAUSE FOR CELEBRATION. In honor of this milestone the museum received 100 new and promised gifts of African, Asian, Oceanic, modern and contemporary art, and photography, many of which you will see in the Acquisitions section of this report. In addition to these gifts, more than 500 longtime patrons and new friends honored and supported exhibitions and programs at the museum by attending a benefit party, “25 Candles,” held September 15. The gifts and funds raised in honor of the Harn’s 25th anniversary totaled more than $1 million. Highlights of the many generous donations and promised gifts to the Harn include 15 works of Tiffany glass and 14 works of Steuben glass given by Relf and Mona Crissey; 10 contemporary Japanese ceramic works promised by Jeffrey and Carol Horvitz; 5 Oceanic works, 3 African objects and one modern painting promised by C. Frederick and Aase B. Thompson; 5 photographic works given by artist Doug Prince; 4 paintings by Tony Robbin given by Norma Canelas Roth and William D. Roth; and a sculpture by Joel Shapiro given by Steve and Carol Shey. A 25th Anniversary Public Celebration was held on September 27 with an attendance of over 600 visitors. On this occasion the Harn rolled out our new free membership program, which offers full participation in the life of the museum for everyone with no financial barriers. The Harn’s six curators worked together to organize an exhibition highlighting 125 works of art selected from all of our collecting areas, Conversations: A 25th Anniversary Exhibition. -

North Carolina Human Trafficking Resource Directory October 2020

North Carolina Human Trafficking Resource Directory October 2020 DISCLAIMER: The NC HTC has not vetted the organizations or persons listed in this directory. Do not construe placement on this directory as an endorsement or recommendation. We encourage you to research and assess each entity. This project was support by Grant number 2018-V2-GX-0061 awarded by the Office of Victims of Crime, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this publication, program/exhibition are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Justice, Office of Victim’s Crime. NC Human Trafficking Resource Directory Important Notes The purpose of this directory is to provide a centralized resource for agencies and groups working to combat human trafficking across the state. The NC Human Trafficking Commission (NC HTC) has not vetted the organizations or persons listed in this directory. Do not construe placement on this directory as an endorsement or recommendation. We encourage all users to research and assess each entity by reviewing agency websites, learning agency mission and values, asking questions about policies, procedures, political or religious affiliations, and previewing admission paperwork or client agreements before determining appropriate fit for referrals. The NC Secretary of State website is also a resource to search for information on a business or charity, including charitable solicitation license status. To search the document for services or location, we recommend using control + find (ctrl + f) Consistent Terminology o Emergency shelter beds: provide 24/7 emergency shelter. To be included in this section, the agency should provide shelter admissions to its target population 24/7, with low barrier requirements. -

Look and Learn a History of the Classic Children's Magazine By

Look and Learn A History of the Classic Children's Magazine By Steve Holland Text © Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 2006 First published 2006 in PDF form on www.lookandlearn.com by Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 54 Upper Montagu Street, London W1H 1SL 1 Acknowledgments Compiling the history of Look and Learn would have be an impossible task had it not been for the considerable help and assistance of many people, some directly involved in the magazine itself, some lifetime fans of the magazine and its creators. I am extremely grateful to them all for allowing me to draw on their memories to piece together the complex and entertaining story of the various papers covered in this book. First and foremost I must thank the former staff members of Look and Learn and Fleetway Publications (later IPC Magazines) for making themselves available for long and often rambling interviews, including Bob Bartholomew, Keith Chapman, Doug Church, Philip Gorton, Sue Lamb, Stan Macdonald, Leonard Matthews, Roy MacAdorey, Maggie Meade-King, John Melhuish, Mike Moorcock, Gil Page, Colin Parker, Jack Parker, Frank S. Pepper, Noreen Pleavin, John Sanders and Jim Storrie. My thanks also to Oliver Frey, Wilf Hardy, Wendy Meadway, Roger Payne and Clive Uptton, for detailing their artistic exploits on the magazine. Jenny Marlowe, Ronan Morgan, June Vincent and Beryl Vuolo also deserve thanks for their help filling in details that would otherwise have escaped me. David Abbott and Paul Philips, both of IPC Media, Susan Gardner of the Guild of Aviation Artists and Morva White of The Bible Society were all helpful in locating information and contacts.