The C Ompendium S Axonis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

Finding Sissa (And Much More) Lisa Lindell

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 29 | Number 2 Article 10 6-1-2009 Finding Sissa (and much more) Lisa Lindell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lindell, Lisa (2009) "Finding Sissa (and much more)," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 29 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol29/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Sissa (and much more) – A journey into the past BY LISA LINDELL In 1997, my article “Searching for There we found a Sissa Jönsdotter are listed on the same page in the Sissa” appeared in the Swedish born in Fogdakärr, Bräkne-Hoby, on village of Agerum.4 Their close American Genealogist.1 Over a dec- the exact date as our Kansas Sissa. proximity explains how they would ade later, I am still engaged in and This Sissa Jönsdotter moved to have known each other prior to Nils’s fascinated by the pursuit of family Gammalstorp parish in 1860 and left immigration to America in 1868 and history. Although I know little Swed- there for America in 1869, shortly the couple’s marriage upon Sissa’s ish beyond a few basic terms and am after my great-great-grandfather arrival in 1869. certainly a genealogy amateur, a Nils Jönsson emigrated from the Even before I became certain of breakthrough in the Sissa search and same parish.3 (Unlike with Sissa, her identity, I had begun searching recent discoveries on a related line Nils’s immediate ancestry and path the Bräkne-Hoby records to find have rekindled my excitement in from Sweden to America were, happi- Sissa Jönsdotter’s ancestry. -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

East Baltic Vikings - with Particular Consideration to the Ctrronians

East Baltic Vikings - with particular consideration to the Ctrronians Swedish Allies in the Saga World EAST BALTIC At the mythical battlefield of Bravellir (Sw. VIKINGS - WITH Bnl.vallama), Danes and the Swedes clashed in a PARTICULAR fight of epic dimensions. The over-aged Danish king Harald Hildetand finally lost his life, and CONSIDERA his nephew king Sigurdr hringr won Denmark TION TO THE for the Swedes. The story appears in a fragment CURONIANS of a Norse saga from around 1300. But since Sa xo Grammaticus tells it, the written tradition Nils Blornkvist must go back at least to the late 12th century. Wri ting in Latin he prefers to call it bellum Suetici, 'the Swedish war'. It's for several reasons ob vious that Saxo has built his text on a Norse text that must have been quite similar to the preser ved fragment. The battle of Bravellir- the Norse fragment claims - was noteworthy in ancient tales for having be en the greatest, the hardest and the most even and uncertain of the wars that had been fought in the Nordic countries.1 Both sources give long lists of the famous heroes that joined the two armies in a way that recalls the list of ships in Homer's Iliad. These champions are the knight errants of Germanic epics, to some degree rela ted with those of chansons de geste. They are pre sented with characteristic epithets and eponyms that point out their origins in a town, a tribe or a country. When summed up they communicate a geographic vision of the northern World in the 11 th and 12th centuries. -

How Uniform Was the Old Norse Religion?

II. Old Norse Myth and Society HOW UNIFORM WAS THE OLD NORSE RELIGION? Stefan Brink ne often gets the impression from handbooks on Old Norse culture and religion that the pagan religion that was supposed to have been in Oexistence all over pre-Christian Scandinavia and Iceland was rather homogeneous. Due to the lack of written sources, it becomes difficult to say whether the ‘religion’ — or rather mythology, eschatology, and cult practice, which medieval sources refer to as forn siðr (‘ancient custom’) — changed over time. For obvious reasons, it is very difficult to identify a ‘pure’ Old Norse religion, uncorroded by Christianity since Scandinavia did not exist in a cultural vacuum.1 What we read in the handbooks is based almost entirely on Snorri Sturluson’s representation and interpretation in his Edda of the pre-Christian religion of Iceland, together with the ambiguous mythical and eschatological world we find represented in the Poetic Edda and in the filtered form Saxo Grammaticus presents in his Gesta Danorum. This stance is more or less presented without reflection in early scholarship, but the bias of the foundation is more readily acknowledged in more recent works.2 In the textual sources we find a considerable pantheon of gods and goddesses — Þórr, Óðinn, Freyr, Baldr, Loki, Njo3rðr, Týr, Heimdallr, Ullr, Bragi, Freyja, Frigg, Gefjon, Iðunn, et cetera — and euhemerized stories of how the gods acted and were characterized as individuals and as a collective. Since the sources are Old Icelandic (Saxo’s work appears to have been built on the same sources) one might assume that this religious world was purely Old 1 See the discussion in Gro Steinsland, Norrøn religion: Myter, riter, samfunn (Oslo: Pax, 2005). -

Fund Og Forskning I Det Kongelige Biblioteks Samlinger

Digitalt særtryk af FUND OG FORSKNING I DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEKS SAMLINGER Bind 51 2012 With summaries KØBENHAVN 2012 UDGIVET AF DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEK Om billedet på smudsomslaget se s. 57. Det kronede monogram på kartonomslaget er tegnet af Erik Ellegaard Frederiksen efter et bind fra Frederik 3.s bibliotek Om titelvignetten se s. 167. © Forfatterne og Det Kongelige Bibliotek Redaktion: John T. Lauridsen Redaktionsråd: Ivan Boserup, Else Marie Kofod, Erland Kolding Nielsen, Anne Ørbæk Jensen, Stig T. Rasmussen, Marie Vest Fund og Forskning er et peer-reviewed tidsskrift. Papir: Scandia 2000 Smooth Ivory 115 gr. Dette papir overholder de i ISO 9706:1994 fastsatte krav til langtidsholdbart papir. Grafisk tilrettelæggelse: Jakob Kyril Meile Tryk og indbinding: SpecialTrykkeriet, Viborg ISSN 0060-9896 ISBN 978-87-7023-093-3 SAXOS BOGINDDELINGER OG DERES IDEOLOGIER af Ivan Boserup & Thomas Riis I. Ivan Boserup: Saxo-kompendiet og Angers-fragmentet 1 ngers-fragmentet af Saxo Grammaticus, i alt fire pergamentblade i A kvartformat fra ca. 1200, blev første gang publiceret i 1879 af over- bibliotekaren ved Det Kongelige Bibliotek Chr. Bruun (1831-1906).2 Der synes siden da at være opnået en slags konsensus om, at fragmen- tet er en autograf: Det er Saxos egen hånd, såvel i hovedteksten som i tilføjelser mellem linjerne og i marginen på bl.a. fol. 1r, se fig. 1. Tilføjelserne repræsenterer to faser af forfatterens videre stilistiske og indholdsmæssige be- og omarbejdning af den renskrevne grundtekst. Den såkaldte “tredje hånd”, der er i en fra resten af fragmentet stærkt afvigende 1300-tals kursivskrift, er den eneste anden hånd repræsente- ret ud over Saxos egen. -

An Encapsulation of Óðinn: Religious Belief and Ritual Practice Among The

An Encapsulation of Óðinn: Religious belief and ritual practice among the Viking Age elite with particular focus upon the practice of ritual hanging 500 -1050 AD A thesis presented in 2015 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Aberdeen by Douglas Robert Dutton M.A in History, University of Aberdeen MLitt in Scandinavian Studies, University of Aberdeen Centre for Scandinavian Studies The University of Aberdeen Summary The cult surrounding the complex and core Old Norse deity Óðinn encompasses a barely known group who are further disappearing into the folds of time. This thesis seeks to shed light upon and attempt to understand a motif that appears to be well recognised as central to the worship of this deity but one rarely examined in any depth: the motivations for, the act of and the resulting image surrounding the act of human sacrifice or more specifically, hanging and the hanged body. The cult of Óðinn and its more violent aspects has, with sufficient cause, been a topic carefully set aside for many years after the Second World War. Yet with the ever present march of time, we appear to have reached a point where it has become possible to discuss such topics in the light of modernity. To do so, I adhere largely to a literary studies model, focussing primarily upon eddic and skaldic poetry and the consistent underlying motifs expressed in conjunction with descriptions of this seemingly ritualistic act. To these, I add the study of legal and historical texts, linguistics and contemporary chronicles. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes. -

The Hostages of the Northmen and the Place Names Can Indicate Traditions That Are Not Related to Hostages

Part V: Place Names Place names can provide information about hostages that can- not be obtained from other sources. In his study of sacred place names in the provinces around Lake Mälaren in present Sweden, Vikstrand points out that these names reflect ‘a social representa- tiveness’ that have grown out of everyday language.1 As a source, they can therefore represent social groups other than those found in the skaldic poetry which were directed to rulers in the milieu of the hird, and thus primarily give knowledge of performances of the elite. There are difficulties with analysis of place names, because sev- eral aspects of them must be considered. Place names are names of places, but Vikstrand points out that in the term ‘place’ you can distinguish three components: a geographical locality, a name, and a content that gives meaning to it.2 The relationship between these components is complicated and it is not always the given geographical location is the right one. For example, local people can ascribe place names an importance that they did not had dur- ing the time the researcher investigates. In this part, the point of departure will be a few place names from mainly eastern Scandinavia and neighboring areas. These are examples of historical provinces in present Sweden, Finland, and Estonia that can provide information about hostages; a com- parison is made with an example from Ireland. In western Scandinavia, corresponding place names with ‘hos- tage’ as component do not appear. There are some problems with these place names: they may be mentioned in just one source, the place names are not contemporary, the etymology can be ambiguous, How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

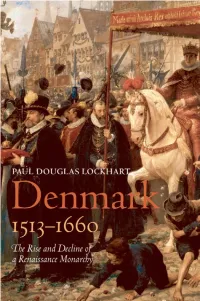

The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy

DENMARK, 1513−1660 This page intentionally left blank Denmark, 1513–1660 The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy PAUL DOUGLAS LOCKHART 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Paul Douglas Lockhart 2007 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lockhart, Paul Douglas, 1963- Denmark, 1513–1660 : the rise and decline of a renaissance state / Paul Douglas Lockhart. -

SAXO GRAMMATICUS HIEROCRATICAL CONCEPTIONS and DANISH HEGEMONY in the THIRTEENTH CENTURY by ANDRÉ MUCENIECKS SAXO GRAMMATICUS CARMEN Monographs and Studies

CARMEN Monographs and Studies CARMEN Monographs SAXO GRAMMATICUS HIEROCRATICAL CONCEPTIONS AND DANISH HEGEMONY IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY by ANDRÉ MUCENIECKS SAXO GRAMMATICUS CARMEN Monographs and Studies Series Editor Dr. Andrea Vanina Neyra Instituto Multidisciplinario de Historia y Ciencias Humanas, CONISET, Buenos Aires SAXO GRAMMATICUS HIEROCRATICAL CONCEPTIONS AND DANISH HEGEMONY IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY by ANDRÉ MUCENIECKS Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress © 2017, Arc Humanities Press, Kalamazoo and Bradford This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercialNoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence. The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of their part of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted provided that the source is acknowledged. Any use of material in this work that is an exception or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/29/EC) or would be determined to be “fair use” under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act September 2010 Page 2 or that satisfies the conditions specified in Section 108 of the U.S. Copy right Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. 94553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. ISBN 9781942401131 eISBN 9781942401140 http://mip-archumanitiespress.org CONTENTS ..................................................................vii List of Illustrations -

Norse Kings' Sagas Spread to the World

Norse Kings’ Sagas Spread to the World Jon Gunnar Jørgensen The University of Oslo 1. The writing of Kings’ sagas The Kings’ sagas are regarded as a separate genre of Icelandic saga litera- ture. They have been, and still are of extraordinary value as sources of Scandinavian history, but also from an aesthetic point of view – as litera- ture. The Kings’ sagas were also the first part of the Icelandic saga treas- ure to awaken the attention abroad in the 16th and 17th centuries. The main subject of these sagas is the lives and political career of Scandinavian, mainly Norwegian, kings from the Viking Age and through the life of King Hakon Hakonsson (d. 1263). It is a mystery how and why this literature developed in the periphery area of Iceland, at a time Icelanders did not even have a king of their own. It is hard to believe that pure historical interest could have been sufficient motiva- tion. Perhaps it was a way to discuss the problematic lack of a Head of State which was prescribed by the medieval models of government. This could be actualised by the serious internal conflicts of the Sturlunga era. The writing of sagas could also be motivated by a request for a cultural capital, as some Icelandic scholars have argued recently, with the refer- ence to the ideas of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (See e. g. Torfi H. Tulinius 2004). Saga manuscripts have also been pointed out as a valuable article of export (see Stefán Karlsson 1979). The Icelandic Saga- codices have no doubt been of great value to the Norwegian aristocracy and the kings of Norway.