Chapter Eight Governance Performance Composite Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leadership of a Rice Farmer's Group in the Salt Intrusion Area, Takhria

Leadership of a Rice Farmer’s Group in the Salt Intrusion Area, Takhria Sub-District, Ranot District, Songkhla Province Wilaiporn Sengwun1* and Pilaiwan Prapruit1 1Department of Agricultural Development, Faculty of Natural Resources, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The objectives of this research were to 1) analyze the leadership characteristics and behaviors of the leaders of a rice farming groups in the salt intrusion area, and 2) analyze the relationship between leadership characteristics and behaviors of the leaders. The data collection tool used in this research was a structured questionnaire. Its purpose was to allow members of rice farming group and local citizens who were aware of the work of the group leader to evaluate the leader in terms of leadership characteristics and behaviors. Questionnaires were analyzed, with responses arranged into 5 levels according to Likert scale, and behaviors were analyzed according to Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid. Results found that, 1) overall leadership characteristics were at a high level ( = 4.13) with the average highest leadership characteristics being the ability to perform tasks ( = 4.30). Physical characteristics came next ( = 4.24), followed풙� by personality characteristics ( = 4.17). An examination of the characteristics showed that풙� the rice farming group leaders possess good풙� human relations skills, with strong effort and풙� patience at the highest level ( = 4.50), and 2) analysis of leader behaviors found that the leaders of the rice farming groups had an average task-oriented behavior score of 5.93, and풙� an averaged relationship- oriented behavior score of 7.47. When comparing these scores with the Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid, leaders of rice farming groups have behaviors that emphasized teamwork (6,8). -

Smoking Behaviour and Associated Factors of Illicit Cigarette Consumption in a Border Province of Southern Thailand

Smoking Behaviour and Associated Factors of Illicit Cigarette Consumption in a Border Province of Southern Thailand Chittawet Ketchoo A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Epidemiology Prince of Songkla University 2011 Copyright of Prince of Songkla University i ii iii iv Thesis Title Smoking Behaviour and associated factors of illicit cigarette consumption in a border province of southern Thailand Author Mr.Chittawet Ketchoo Major Programme Epidemiology Academic year 2010-2011 ____________________________________________________________ Abstract Background: Consumption of illicit cigarettes poses a serious threat to public health as well as being a source of huge losses in government revenues. It brings tobacco onto the market cheaply, making cigarettes more affordable and thus stimulating consumption, especially among the youth group, consequently increasing the burden of ill-health. Illicit cigarette sabotages national tobacco taxation and tobacco control strategies and has become a major concern for governments and international organizations. Therefore, it is important to understand this problem thoroughly in order to reduce it. The high magnitude of illicit cigarette trade in southern Thailand offers an opportunity to examine the situation of illicit cigarette consumption. Objectives: To investigate behaviours and factors associated with illicit cigarette consumption in southern Thailand. Methodology: A survey and qualitative study were conducted in a border province in southern Thailand next to Malaysia. A modified snowballing technique was used to recruit 300 illicit and 150 non-illicit cigarette smokers. A structured questionnaire v was used to interview subjects. Smoking behaviours and associated factors with illicit cigarette consumption were analysed by complex survey regression adjusted for a cluster of samples identified by each recruiter. -

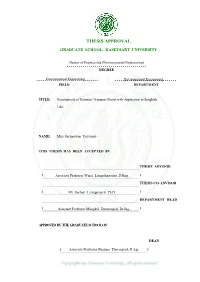

Development of Sediment Transport Model with Application to Songkhla Lake

THESIS APPROVAL GRADUATE SCHOOL, KASETSART UNIVERSITY Doctor of Engineering (Environmental Engineering) DEGREE Environmental Engineering Environmental Engineering FIELD DEPARTMENT TITLE: Development of Sediment Transport Model with Application to Songkhla Lake NAME: Miss Sucheewan Yoyrurob THIS THESIS HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THESIS ADVISOR ( Associate Professor Winai Liengcharernsit, D.Eng. ) THESIS CO-ADVISOR ( Mr. Suchart Leungprasert, Ph.D. ) DEPARTMENT HEAD ( Assistant Professor Mongkol Damrongsri, Dr.Ing. ) APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE SCHOOL ON DEAN ( Associate Professor Gunjana Theeragool, D.Agr. ) THESIS DEVELOPMENT OF SEDIMENT TRANSPORT MODEL WITH APPLICATION TO SONGKHLA LAKE SUCHEEWAN YOYRUROB A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Engineering (Environmental Engineering) Graduate School, Kasetsart University 2011 Sucheewan Yoyrurob 2011: Development of Sediment Transport Model with Application to Songkhla Lake. Doctor of Engineering (Environmental Engineering), Major Field: Environmental Engineering, Department of Environmental Engineering. Thesis Advisor: Associate Professor Winai Liengcharernsit, D.Eng. 165 pages. In the past few decades, rapid population growth in Thailand has resulted in excess utilization of natural resources and degradation of environmental quality. Deforestation in sloping areas for agricultural and residential purposes has resulted in soil erosion from deforested areas with subsequent sediment transport and deposition in receiving water bodies. In order to evaluate the severity of this problem, a mathematical model is developed to simulate sediment transport phenomena in a receiving water body. In model development, total sediment transport is classified as bedload transport and suspended load transport, which result in two interrelated transport models. Three-dimensional mass balance equation is used as a basic governing equation for the suspended load transport model, whereas two-dimensional mass balance equation is used as a basic governing equation for the bedload transport model. -

OF WAT MATCHIMAWAT (WAT KLANG), SONGKHLA PROVINCE, THAILAND by Pensuda Chounchaisit a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

THE STUDY OF CULTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT OF WAT MATCHIMAWAT (WAT KLANG), SONGKHLA PROVINCE, THAILAND By Pensuda Chounchaisit A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism (International Program) Graduate School SILPAKORN UNIVERSITY 2007 PDF Creator - PDF4Free v2.0 http://www.pdf4free.com The Graduate School, Silpakorn University has approved and accredited the Thesis title of “The Study of Cultural Heritage Management of Wat Matchimawat (Wat Klang), Songkhla Province, Thailand” submitted by Ms. Pensuda Chounchaisit as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism. …………………………………………… (Associate Professor Sirichai Chinatangkul, Ph.D.) Dean, Graduate School …………./ …………………../ …………. The Thesis Advisor Professor Ken Taylor The Thesis Examination Committee …………………………………………………. Chairman (Professor Trungjai Buranasomphob, Ph.D.) …………./ ……………………/ …………. …………………………………………………. Member (Assistant Professor Chaiyasit Dankittikul, D.E.D.) …………./ …………………../ …………. …………………………………………………. Member (Professor Ken Taylor) …………./ …………………../ …………. PDF Creator - PDF4Free v2.0 http://www.pdf4free.com 45056960: MAJOR: ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT AND TOURISM KEYWORD: CULTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT, WAT MATCHIMAWAT PENSUDA CHOUNCHAISIT: THE STUDY OF CULTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT OF WAT MATCHIMAWAT (WAT KLANG), SONGKHLA PROVINCE, THAILAND. THESIS ADVISOR: PROF. KEN TAYLOR. 171 pp. This study -

Nakhon Si Thammarat Phatthalung Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan CONTENTS

Nakhon Si Thammarat Phatthalung Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan CONTENTS NAKHON SI THAMMARAT 11 Boundary 11 How to get there 12 Attractions 12 Events and Festivals 44 Restaurants and Accomodation 45 Important Telephone Numbers 45 PHATTHALUNG 46 Boundary 47 How to get there 47 Attractions 48 Events and Festivals 66 Restaurants and Accomodation 67 Important Telephone Numbers 67 NAKHON SI THAMMARAT NAKHON SI THAMMARAT NAKHON SI THAMMARAT NAKHON SI THAMMARAT Nakhon Si Thammarat Ban Laem Prathap Chinese-style buildings at Hat Khwaeng Phao Wat Pradu and Wat Chaeng Wildlife Conservation and Extension Station Coral Pagoda Hat Thong Ching (Khao Phlai Dam) 4044 Tham Khao Krot Wat Wang Tawan Tok 4142 Chedi Yak Hat Kho Khao Khanom City Pillar Shrine Sanam Na Mueang Public Park Phra Wihan Sung and Si Thammasokarat Park Hat Khanom - Muko Old City Wall Thale Tai National Park 4014 Ho Phra Isuan and the Giant 401 Swing and Ho Phra Narai Ho Phra Phuttha Sihing 3009 Ban Nang Talung Nakhon Si Thammarat Hat Thung Sai National Museum Suchart Subsin Wat Phra Mahathat Baan Tan Khun Namtok Si Khit National Park Sichon Hat Sichon Woramahawihan Hat Hin Ngam Hat Kho Khao Wat Suan Luang Nakhon Si Thammarat 401 Bangkok City Museum Khao Kha Archaeological Site Khao Nan National Park Khao Liam Viewpoint Rafting along Khlong Klai Khao Lek Viewpoint Khao Chang Lon Viewpoint 4188 Krung Ching Hot Spring 4186 3008 401 Namtok Krung Ching Hat Sai Kaeo Museum Nakhon Si Thammarat Nopphitam Hat Sai Kaeo 4016 Tha Sala Hat Dan Phasi Tum Pang Archaeological Site Ban Nai Thung Ban Maying Pottery-making Group Kathun 401 Reservoir 4224 Wat Mo Khlan Archaeological Site Namtok Ai Khiao Phipun Wat Khao Khun Phanom Namtok Phrom Lok Nakhon Si Thammarat Science Centre Phrom Lok Community-based Tourism Centre Pak Phanang Coast and Yot Khao Sun Viewpoint 4104 4194 Phrom Khiri Ban Mamuang Plai Khaen Laem Talumphuk 4015 Pha Yok Nakhon Weaving 4016 Group Tham Phannara Chawang BanKhiri Wong Ban Pak Nakhon 4228 4015 Pak Phanang Retro Market Khao Luang 4070 NAKHON SI THAMMARAT Muko Kra National Park 55 Km. -

Appendix 3 Selection of Candidate Cities for Demonstration Project

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report APPENDIX 3 SELECTION OF CANDIDATE CITIES FOR DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Table A3-1 Long List Cities (No.1-No.62: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-1 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-2 Long List Cities (No.63-No.124: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-2 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-3 Long List Cities (No.125-No.186: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-3 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-4 Long List Cities (No.187-No.248: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-4 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-5 Long List Cities (No.249-No.310: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-5 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-6 Long List Cities (No.311-No.372: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. -

Coastal Shrimp Aquaculture in Thailand: Key Issues for Research

Coastal Shrimp Aquaculture in Thailand: Key Issues for Research Editor: Paul T. Smith Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra 1999 The Australian Centre for International Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agricul- tural problems in developing countries and commission research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has special research competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimina- tion against any product by the Centre. ACIAR TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES This series of publications contains technical information resulting from ACIAR-supported programs, projects and workshops (for which proceedings are not published), reports on Centre-supported fact-finding studies, or reports on other useful topics resulting from ACIAR activities. Publications in the series are distributed internationally to a selected audience. © Australian Centre for International Agriculture Research, GPO Box 1571, Can- berra, ACT 2601 Australia. Email:<[email protected]>. Home page: <http://aciar. gov.au>. Smith, P.T., ed. 1999. Coastal shrimp aquaculture in Thailand: key issues for research. ACIAR Technical Reports No. 47, 131p. ISBN 1 86320 273 0 Typesetting and layout: Arawang Communication Group, Canberra. ! Contents Preface 5 Acknowledgments 6 Glossary and abbreviations 6 Executive Summary 7 Paul T. Smith, Hassanai Konkeo, Siri Tookwinas and Michael J. Phillips An -

Tourism Route Culture, Local Lifestyle and Job Creation

Tourism Route (1 Day) Wat Pha Kho or Wat Ratchapraditsathan Culture, Local Lifestyle and Job Creation 1 (Sathing Phra District) Day The temple is one of the most ancient and renowned temples on Sathing Phra Peninsula, with Tourism Route (Mueang District) Wat Thai Yo or a history dating back to the reign of King Ramathibodi 1 Thai Yo Temple II of Ayutthaya Period. Phra Suwan Malik Chedi, the Day Langka style chedi, is enshrined on the top of Pha Wat Thai Yo is an ancient temple in Culture, Local Lifestyle Kho Mountain. It is one of the most sacred and Ko Yo. It has the precious architectural highly revered by the southern locals. The most and Job Creation style of a traditional Southern Thai abode significant feature of Pha Kho temple is that Luang or kuti which the 200-year-old abode is Pho Thuat, one of the most highly respected by Thai Buddhists. Hence, this temple is recognized entirely made of wood and the roof are as a sacred land of Luang Pho Thuat, a revered monk whose steps turned saltwater into tiled with Ko Yo local terracotta tiles. Overall freshwater. 1 atmosphere is shady, simply and serene. Khlong Daen Floating Day Market (Ranot District) Suan Lung Wee This market is one of cultural attractions and it is Suan Lung Wee is garden that using multilayer 1 also conservation tourism in Ranot District. It is located cropping system, or what the locals call “Suan Som Day right at the junction of three canals and it is a natural Rom” (Som Rom in the southern language means to boundary between the two provinces. -

Incentive for Shifts in Water Management Systems by Shrimp Culturists in Southern Thailand

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKFISFisheries Science0919-92682005 Blackwell Science Asia Pty Ltd 2005714791798Original ArticleIncentive for shift in water managementC Kasai et al. FISHERIES SCIENCE 2005; 71: 791–798 Incentive for shifts in water management systems by shrimp culturists in southern Thailand Chifumi KASAI,1 Thongchai NITIRATSUWAN,2 Osamu BABA3 AND Hisashi KUROKURA1* 1Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan, 2Faculty of Science and Fisheries Technology, Rajamangala Institute of Technology, Trang 92150, Thailand and 3Faculty of Fisheries, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, Tokyo 108-8477, Japan ABSTRACT: Water management systems and other business situations of shrimp culturists were surveyed in two districts in southern Thailand. There were three types of water management systems in southern Thailand, namely closed, semiclosed and open systems, categorized by the frequency of exchange of pond water. Shrimp culturists in those districts tended to shift their system from the open system to the closed system of their own accord, and the average net income ratio decreased due to the change of water management system in a district from more than 2 to less than 1. The reason for this shift, in spite of the decrease in the profit rate, was prevention of infectious disease caused by water exchange. In conclusion, it was proven that independent shrimp culturists, such as medium and small scale shrimp pond owners in southern Thailand, would accept short-term decreases in profit rate in order to stabilize production. KEY WORDS: closed system, incentive, shrimp culture, Thailand, water management. INTRODUCTION propagation of infectious disease and degradation of environment, such as cutting down the stocking Cultured shrimps are the main product for export density and feeding levels, are unpopular with in several developing countries. -

Informal Learning of Thai Chinese in Songkhla Province Through Qingming Tradition

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 3; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Informal Learning of Thai Chinese in Songkhla Province through Qingming Tradition Buakaew Jureerat1 & Janjula Jiraporn1 1 Faculty of Liberal Arts, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand Correspondence: Buakaew Jureerat, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand. Tel: 66-74-28-6751. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 3, 2013 Accepted: January 6, 2014 Online Published: January 27, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n3p138 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n3p138 Abstract This qualitative study aimed to investigate the informal learning of Thai Chinese in Songkhla Province through Qingming tradition. The data were collected from in-depth interviews and participatory observations with 30 subjects who were Thai Chinese. The results of the study revealed that Thai Chinese in Songkhla Province learn Quingming tradition through adults in their family since they were children. Adults teach, practice and take children with them to perform rituals on Qingming Day. Children take part with interest and when they grow up and become teenagers, they participate in the tradition by helping to prepare items that are used in worshiping their ancestors. When they become adults and have a career to earn a living, they are assigned to prepare all the worship items for the rituals every year as their parents get old. Thus, this is the way Qingming tradition is learned by Thai Chinese; they learn it informally as the tradition is passed down from one generation to the next. -

Chapter 3 Coastal Conditions in Study Area

Chapter 3 Coastal Conditions in Study Area In Figure 3.1-1, the direction of longshore drift (which was estimated by the observation of the deposition and/or erosion states around coastal structures and of the present shoreline situation on the sites) is indicated by arrows. 3.1.1 Khanom District Most of the coastal line in this district is composed of rocky capes and some sandy beaches. These sandy beaches are located between the capes. Therefore, the shoreline in this district is rather stable. Khanom port is located at the river mouth of Khlong Ban Tha Chan between Khao Chai Son and Khao Phi Hai. In the north part of the river mouth to the Khanom port, small parts of sandy beach are reported to be slightly eroded. 3.1.2 Sichon District Sichon port with single jetty at the left side of the river mouth is located at the north of Laem Khao Kho Kwang and the right side of the river mouth is composed of rocks. The littoral drift in this area is not seen to be serious except for the beach erosion in the north part of the existing jetty. In the south part of Laem Khao Kho Kwang, there are several small fishing ports which are located at river mouths without jetty, such as Khlong Tung Ca (Thepha), Tha Mak in Sichon district and Pak Duat, Bang San in Tha Sala district. The river mouths of these fishing ports are characterized by river-mouth closure. The channels to these fishing ports cannot be maintained without periodic dredging. -

Coastal Management in Pak Phanang: a Historical Perspective of the Resources and Issues

Old town of Pak Phanang. .t1*.,,* - ....s APPENDIX 1 near the mouth of the river. There are many housesalong the side of the river, as the populationin the town is over 46,000. Letter From King Rama V There are a lot of Chinese,mainly Hainan; to the Crown Prince a few are Hock Kien and there is a small group of Tae Chew. The people greeted Chakd Royal Barge me from their boats along the river. Our 9 July 1905 boatmeandered along the river andbrought me to the new rice mill named after Koh Dear Crown Prince of Siam, Hak Gnee. The Hak Gnee familv invited me to open the ceremony, I was served This is more information to report to you, Chinesesoup at thedistrict officer's house, following my previousletter. the new district office is as big as the one beingbuilt in Pattani.The commissioners In themorning of the8th of July at9:00 am, and the sailors were served Thai food. a fast dugouttook me to PakPhanangfrom Plenty of presentswere prepared for the Nakhon Bay, which is at the bottom of King, suchas rice, sugar, fruits, sweetsand Laem Talumpuk. The trip took almost medicines. Crowds of people were three hours; we used the dugout not for waiting to praisethe King, both on the land enjoyment but becausethe water is and alongsidethe river. There were Thai, shallow.The PakPhanang River is aswide Chineseand Malaysianculture shows. I as Chao Praya River in Bangkok. The left about 3:30 pm and returned to the house of a district head officer is situated Chakd Bargeat about8:00 pm.