Information Bulletin No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Commanders of the LTTE

4/29/2016 List of commanders of the LTTE Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of commanders of the LTTE From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of commanders of theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a separatist militant Tamil nationalist organisation, which operated in northern and eastern Sri Lanka from late 1970s to May 2009, until it was defeated by the Sri Lankan Military.[1][2] Date & Place Date & Place Nom de Guerre Real Name Position(s) Notes of Birth of Death Thambi (used only by Velupillai 26 November 1954 19 May Leader of the LTTE Prabhakaran was the supreme closest associates) and Prabhakaran † Velvettithurai 2009(aged 54)[3][4][5] leader of LTTE, which waged a Anna (elder brother) Vellamullivaikkal 25year violent secessionist campaign in Sri Lanka. His death in Nanthikadal lagoon,Vellamullivaikkal,Mullaitivu, brought an immediate end to the Sri Lankan Civil War. Pottu Amman alias Shanmugalingam 1962 18 May 2009 Leader of Tiger Pottu Amman was the secondin Papa Oscar alias Sivashankar † Nayanmarkaddu[6] (aged 47) Organization Security command of LTTE. His death was Sobhigemoorthyalias Kailan Vellamullivaikkal Intelligence Service initially disputed because the dead (TOSIS) and Black body was not found. But in Tigers October 2010,TADA court judge K. Dakshinamurthy dropped charges against Amman, on the Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, accepting the CBI's report on his demise.[7][8] Selvarasa Shanmugam 6 April 1955 Leader of LTTE since As the chief arms procurer since Pathmanathan (POW) Kumaran Kankesanthurai the death of the origin of the organisation, alias Kumaran Tharmalingam Prabhakaran. -

Emergency Rule and Authoritarianism in Republican Sri Lanka

6 An Eager Embrace: Emergency Rule and Authoritarianism in Republican Sri Lanka Deepika Udagama Introduction Much of Sri Lanka’s post-independence period has seen governance under states of emergency. The invocation of the Public Security Ordinance (PSO)1 by successive governments was a common feature of political life and, indeed, an integral aspect of the political culture of the republic. Several generations of Sri Lankans have grown up and have been socialised into political and public life in an environment fashioned by states of exception replete with attendant symbols and imagery. Images of police with automatic weapons, military check-points, barbed wire, lengthy periods of detention (often administrative detention) mainly of the political ‘other’, the trauma of political violence and the ever- present sense of fear became the ‘normal’. The state of exception has become the norm in Sri Lanka from the 1970s onwards. The permanency of the state of exception was further consolidated when the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act, No. 48 of 1979 (PTA) was converted into a permanent law in 1982.2 Although not an emergency regulation, the PTA conferred extraordinary powers on the executive branch (e.g. powers of arrest and detention) to deal with what it recognised as acts of terrorism. That in combination with the ever-present emergency powers, which were sanctioned by the Constitution, provided a formidable legal framework to entrench the state of exception. The omnipotence of the executive presidency created by the second republican constitution (1978) amplified the potency of those exceptional powers. Sri Lanka had become the quintessential ‘National Security State’, the vestiges of which have not been shaken off even five The author wishes to thank Ms. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

India's Sri Lanka Policy

APRIL 2008 IPCS Research Papers IInnddiiaa ’’ss SSrrii LLaannkkaa PPoolliiccyy Towards Economic Engagement BBrriiaann Orllaanndd IInnssttiittuuttee ooff PPeeaaccee aanndd CCoonnflliicctt SSttuuddiieess NNeww DDeellhh1 ii,, IINNDDIIAA @ 2008, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS) The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies is not responsible for the facts, views or opinion expressed by the author. The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS), established in August 1996, is an independent think tank devoted to research on peace and security from a South Asian perspective. Its aim is to develop a comprehensive and alternative framework for peace and security in the region catering to the changing demands of national, regional and global security. Address: B 7/3 Lower Ground Floor Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi 110029 INDIA Tel: 91-11-4100 1900, 4165 2556, 4165 2557, 4165 2558, 4165 2559 Fax: (91-11) 4165 2560 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ipcs.org CONTENTS Executive Summary............................................................................................................. 4 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 3 India’s Strategic Interests in Sri Lanka............................................................................... 6 India’s Sri Lanka Policy: An Assessment............................................................................ 9 The Road Ahead.................................................................................................................22 -

India's Sri Lanka Policy

APRIL 2008 IPCS Research Papers IInnddiiaa ’’ss SSrrii LLaannkkaa PPoolliiccyy Towards Economic Engagement Brian OOrrlaandd IInnsstiittute oof Peeaaccee aanndd CCoonflicctt SStudieess NNeew DDellh1 ii,, IINDDIIA @ 2008, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS) The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies is not responsible for the facts, views or opinion expressed by the author. The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS), established in August 1996, is an independent think tank devoted to research on peace and security from a South Asian perspective. Its aim is to develop a comprehensive and alternative framework for peace and security in the region catering to the changing demands of national, regional and global security. Address: B 7/3 Lower Ground Floor Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi 110029 INDIA Tel : 91-11-4100 1900, 4165 2556, 4165 2557, 4165 2558, 4165 2559 Fax : (91-11) 4165 2560 Email : [email protected] Web: www.ipcs.org CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 India and Sri Lanka: A Short Note............................................................................................. 4 India’s Strategic Interests in Sri Lanka....................................................................................... 7 India’s Sri Lanka Policy: An Assessment................................................................................ -

A Study of Violent Tamil Insurrection in Sri Lanka, 1972-1987

SECESSIONIST GUERRILLAS: A STUDY OF VIOLENT TAMIL INSURRECTION IN SRI LANKA, 1972-1987 by SANTHANAM RAVINDRAN B.A., University Of Peradeniya, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1988 @ Santhanam Ravindran, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date February 29, 1988 DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT In Sri Lanka, the Tamils' demand for a federal state has turned within a quarter of a century into a demand for the independent state of Eelam. Forces of secession set in motion by emerging Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism and the resultant Tamil nationalism gathered momentum during the 1970s and 1980s which threatened the political integration of the island. Today Indian intervention has temporarily arrested the process of disintegration. But post-October 1987 developments illustrate that the secessionist war is far from over and secession still remains a real possibility. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

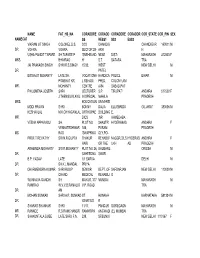

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

"Early Militancy" from " Tigers of Lanka"

www.tamilarangam.net "Early militancy" from " Tigers of Lanka" [Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] [Part 4] [Part 5] This is the 1st part of "Early militancy" from " Tigers of Lanka", written by M.R.Nayaran Swamy. This chapter has the history of Sivakumaran and others. Early Militancy ( Part 1 ) It is VIRTUALLY impossible to set a date for the genesis of Tamil militancy in Sri Lanka. Tamils began weaving dreams of an independent homeland much more militancy erupted, albeit in an embryonic form, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After 1956 riots, a group of tamils organised and opened fire at the Sri Lankan army in Batticaloa. Two Sinhalese were killed when 11 Tamils, having between them seven rifles, fired at a convoy of Sinhalese civi- lians and govt officials one night at a village near Kalmunai. There was another attcak on army soldiers in Jaffna after Colombo stifled the Federal Party "satyagraha" in 1961, but no one was killed. The failure of the 1961 "satyagraha" set several of its leading lights thinking. Mahatma Gandhi, they argued, succeeded in India with his concept of non-violence and non-cooperation because he was leading a majority against a minority, however powerful; whereas in Sri Lanka, the Tamils were a minority seeking rights from a majority. And the majority was not willing to give concessions. Some of 20 men associated with the Federal Party thought Gandhism had no place in sucha scenario. They decided after the prolonged deliberations to form an underground group to fight for a separate state. Most of them were civil servants and had been influenced by Leon Uris Exodus. -

The Sri Lankan Insurgency: a Rebalancing of the Orthodox Position

THE SRI LANKAN INSURGENCY: A REBALANCING OF THE ORTHODOX POSITION A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Stafford Roberts Department of Politics and History, Brunel University April 2016 Abstract The insurgency in Sri Lanka between the early 1980s and 2009 is the topic of this study, one that is of great interest to scholars studying war in the modern era. It is an example of a revolutionary war in which the total defeat of the insurgents was a decisive conclusion, achieved without allowing them any form of political access to governance over the disputed territory after the conflict. Current literature on the conflict examines it from a single (government) viewpoint – deriving false conclusions as a result. This research integrates exciting new evidence from the Tamil (insurgent) side and as such is the first balanced, comprehensive account of the conflict. The resultant history allows readers to re- frame the key variables that determined the outcome, concluding that the leadership and decision-making dynamic within the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had far greater impact than has previously been allowed for. The new evidence takes the form of interviews with participants from both sides of the conflict, Sri Lankan military documentation, foreign intelligence assessments and diplomatic communiqués between governments, referencing these against the current literature on counter-insurgency, notably the social-institutional study of insurgencies by Paul Staniland. It concludes that orthodox views of the conflict need to be reshaped into a new methodology that focuses on leadership performance and away from a timeline based on periods of major combat. -

Bathiudeen Ordered to Reforest Kallaru at Own Cost

HIGHLIGHTS TUESDAY 17 november 2020 Battling Smog LATEST EDITION to Prevent VOL: 09/276 PRICE : Rs 30.00 Covid Pandemic Spread In Sports Poor progress PAGE A6 results in two athletes losing IOC Remittances funding continue Two track and field athletes, Vidusha Lakshani and Gayanthika to rise Abeyrathne, have been removed from the Sri Lanka’s... A16 PAGE B11 COVID-19 Death Review Committee Bathiudeen Ordered hands over report Three deaths reported yesterday to Reforest Kallaru BY DILANTHI JAYAMANNE, GAGANI WEERAKOON, METHMALIE DISSANAYAKE AND BUDDHIKA SAMARAWEERA The COVID-19 death toll increased to 61 with the at Own Cost deaths of three persons which included an 84- year- old woman from Moratuwa, the Government Information Department, quoting the Director Court rules Forest Conservation Polluter pays General Health Services said. The Department said that the 84-year old from Ordinance contravened principle applied Moratuwa had died at her home due to complications from a diabetic condition arising as a result of COVID-19. The deaths also included that of a 70-year-old CG of Forests to Cost to be paid man from Colombo 10 who had been admitted to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID). The calculate cost and within two months cause of death was due to a chronic kidney disease aggravated by COVID-19, and a 75-year-old man from Colombo 13 who had died while being admitted inform Bathiudeen of judgment to the National Hospital due to complications arising from diabetes and congenital heart disease which BY FAADHILA THASSIM AND EUNICE Forest Conservation Ordinance, is in was heightened by COVID-19. -

NONSTATE ARMED GROUPS' USE of DECEPTION a Thesis

STRATAGEM IN ASYMMETRY: NONSTATE ARMED GROUPS’ USE OF DECEPTION A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy By DEVIN DUKE JESSEE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy AUGUST 2011 Dissertation Committee Dr. Richard H. Shultz, Jr. (The Fletcher School), Chair Dr. Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr. (The Fletcher School), Reader Dr. Rohan K. Gunaratna (Rajaratnam School of International Studies), Reader CURRICULUM VITAE DEVIN D. JESSEE EDUCATION THE FLETCHER SCHOOL , TUFTS UNIVERSITY MEDFORD , MA Ph.D. Candidate in International Relations Current • Dissertation title: “Stratagem in Asymmetry: Nonstate Armed Groups’ Use of Deception” • Fields of study: international security, negotiation/conflict resolution, and international organizations. Comprehensive exams passed in May 2006. M.A. in Law and Diplomacy May 2005 • Thesis title: “Strengthening the Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Weapons Nonproliferation Regimes” • Fields of study: international security and negotiation/conflict resolution BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO , UT B.A. in International Politics (Minor in History) August 2003 summa cum laude ACADEMIC HONORS FLETCHER SCHOLARSHIP 2003 – 2004, 2007 – 2011 • Awarded by The Fletcher School based on merit and need. EISENHOWER -ROBERTS FELLOWSHIP 2008 – 2009 • Awarded to Ph.D. students from selected universities to support the intellectual growth of potential leaders. TUFTS UNIVERSITY PROVOST FELLOWSHIP 2005 – 2007 • Awarded to a small number of outstanding Tufts doctoral students. iii H. B. EARHART FELLOWSHIP 2003 – 2006 • Intended to encourage young academics to pursue careers in a social science or the humanities. FRANK ROCKWELL BARNETT FELLOWSHIP 2004 – 2006 • Awarded by the International Security Studies Program at The Fletcher School for academic excellence. -

FOR Resources Development International Foundation, Asia ADMINISTRATION: (Incorporation) Bill – [The Hon

192 වන කාණ්ඩය - 1 වන කලාපය 2010 ජූලි 20 වන අඟහරුවාදා ெதாகுதி 192 - இல. 1 2010 ைல 20, ெசவ்வாய்க்கிழைம Volume 192 - No. 1 Tuesday, 20th July, 2010 පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු විවාද (හැන්සාඩ්) பாராமன்ற விவாதங்கள் (ஹன்சாட்) PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) නිල වාර්තාව அதிகார அறிக்ைக OFFICIAL REPORT (අෙශෝධිත පිටපත /பிைழ தித்தப்படாத /Uncorrected) අන්තර්ගත පධාන කරුණු නිෙව්දන: ධමිම්ක කිතුල ්ෙගොඩ මහතා වැඩ බලන පාර්ලිෙම්න්තුෙව් මහ ෙල්කම් රාමකිෂ්ණ සාරදා දූත ෙමෙහවර (ලංකා ශාඛාව) (සංස්ථාගත කිරීෙම්) – ෙලස පත් කිරීම [ගරු ඒ. විනායගමූර්ති මහතා] –පළමු වන වර කියවන ලදී කථානායකතුමාෙග් සහතිකය ටී.බී. ඒකනායක පදනම (සංස්ථාගත කිරීෙම්) – [ගරු ෙනරන්ජන් පශ්නවලට වාචික පිළිතුරු විකමසිංහ මහතා] – පළමු වන වර කියවන ලදී ෙපෞද්ගලිකව දැනුම් දීෙමන් ඇසූ පශ්නය: විශ්වවිදාල ආචාර්යවරුන් මුහුණ පා සිටින පශ්න අනුරාධපුර ශී පුෂ්පදාන සංවර්ධන පදනම (සංස්ථාගත කිරීෙම්) – වරපසාද: [ගරු ආචාර්ය සරත් වීරෙසේකර මහතා] – පළමු වන වර කියවන උපෙද්ශක කාරක සභාවලට සහභාගි වීමට ඉඩ ෙනොදීම ලදී අධිකරණ සංවිධාන (සංෙශෝධන) පනත් ෙකටුම්පත: වැන්දඹු සහ අනත්දරු විශාම අරමුදල් (සංෙශෝධන) පනත් ෙකටුම්පත: පළමු වන වර කියවන ලදී ෙදවන වර සහ තුන් වන වර කියවා සංෙශෝධිතාකාරෙයන් සම්මත කරන ෙපෞද්ගලික මන්තීන්ෙග් පනත් ෙකටුම්පත්: ලදී ආසියානු, ජපන්, ශී ලංකා හා ඇෙමරිකා, ජර්මන් සමාජයීය ආර්ථික හා වැන්දඹු පුරුෂ සහ අනත්දරු විශාම වැටුප් (සංෙශෝධන) පනත් ෙකටුම්පත: මානව සම්පත් සංවර්ධන ජාතන්තර පදනම (සංස්ථාගත කිරීෙම්) ෙදවන වර සහ තුන් වන වර කියවා සංෙශෝධිතාකාරෙයන් සම්මත කරන ලදී – ගරු තිස්ස අත්තනායක මහතා] පළමු වන වර කියවන ලදී [ පරිපාලන කටයුතු පිළිබඳ පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු ෙකොමසාරිසවරයා් : ෙකොටසර පියංගල රජමහා විහාරස්ථ සංවර්ධන සභාව (සංස්ථාගත වැටුප කිරීෙම්) – [ගරු ආර්.එම්.