Skyscraper Height

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

READING and WRITING Intro

READING AND WRITING Intro Sabina Ostrowska Kate Adams with Wendy Asplin Christina Cavage HOW PRISM WORKS WATCH AND LISTEN 1 Video Setting the context Every unit begins with a video clip. Each video serves PREPARING TO WATCH 1 Work with a partner and answer the questions. ACTIVATING YOUR as a springboard for the unit and introduces the KNOWLEDGE 1 What are five things that you do every day? 2 What jobs do people in the mountains do? What do you think they do every day? topic in an engaging way. The clips were carefully 3 What jobs do people on islands do? What do you think they do every day? selected to pique students’ interest and prepare 4 What do you think is better, living in the mountains or living on an them to explore the unit’s topic in greater depth. As island? Why? 2 Match the sentences to the pictures (1–4) from the video. PREDICTING CONTENT they work, students develop key skills in prediction, USING VISUALS a The women wear colorful clothes. b The woman is caring for a plant. c There is a village on the island. comprehension, and discussion. d The man is catching food to eat. GLOSSARY coast (n) the land next to the ocean deep (adj) having a long distance from top to bottom, like the middle of the ocean culture (n) the habits and traditions of a country or group of people sweep (v) to clean, especially a floor, by using a broom or brush raise (v) to take care of from a young age 60 UNIT 3 SCANNING TO FIND WHILE READING INFORMATION 4 Scan the texts. -

Lbbert Wayne Wamer a Thesis Presented to the Graduate

I AN ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE USE BUILDING; by lbbert Wayne Wamer A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering Lehigh University 1982 TABLE OF CCNI'ENTS ABSI'RACI' 1 1. INTRODlCI'ICN 2 2. THE CGJCEPr OF A MULTI-USE BUILDING 3 3. HI8rORY AND GRami OF MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS 6 4. WHY MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS ARE PRACTICAL 11 4.1 CGVNI'GJN REJUVINATICN 11 4. 2 EN'ERGY SAVIN CS 11 4.3 CRIME PREVENTIOO 12 4. 4 VERI'ICAL CANYOO EFFECT 12 4. 5 OVEOCRO'IDING 13 5. DESHN CHARACTERisriCS OF MULTI-USE BUILDINCS 15 5 .1 srRlCI'URAL SYSI'EMS 15 5. 2 AOCHITECI'URAL CHARACTERisriCS 18 5. 3 ELEVATOR CHARACTERisriCS 19 6. PSYCHOI..OCICAL ASPECTS 21 7. CASE srUDIES 24 7 .1 JOHN HANCOCK CENTER 24 7 • 2 WATER TOiVER PlACE 25 7. 3 CITICORP CENTER 27 8. SUMMARY 29 9. GLOSSARY 31 10. TABLES 33 11. FIGJRES 41 12. REFERENCES 59 VITA 63 iii ACKNCMLEI)(}IIENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr. Lynn S. Beedle for the supervision of this project and review of this manuscript. Research for this thesis was carried out at the Fritz Engineering Laboratory Library, Mart Science and Engineering Library, and Lindennan Library. The thesis is needed to partially fulfill degree requirenents in Civil Engineering. Dr. Lynn S. Beedle is the Director of Fritz Laboratory and Dr. David VanHom is the Chainnan of the Department of Civil Engineering. The author wishes to thank Betty Sumners, I:olores Rice, and Estella Brueningsen, who are staff menbers in Fritz Lab, for their help in locating infonnation and references. -

Feature Property

Woolworth Building An early skyscraper, National Historic Landmark since 1966, and New York City landmark since 1983, the Woolworth Building was the tallest building in the world upon completion in 1913 until 1930. 233 Broadway New York, NY Neo-Gothic Style Façade Architectural Details Straight lines of the “piers” ascend upwards to the over-scaled pyramidal cap Top Portion of Building 57th Floor Observation Deck until 1940 Building Use Transition U-Shaped Portion- 29 Stories Tall Top 30 Floors Conversion to Luxury Residential Condominiums Lobby Details Marble Finishes Vaulted Ceiling Mosaics Stained-Glass Ceiling Light Bronze Fittings PROJECT SUMMARY Project Description A classic early high-rise architectural landmark incorporating Gothic themes with the modern idea of a skyscraper. The 1913 Gothic Revival building featured gargoyles, arches and flying buttresses. Bordered by Broadway, Barclay Street, Church Street, and Park Place, the building is located in New York City’s Financial District. Building Description 57 floor, Neo-Gothic designed, steel-rigid frame structure with light gray, limestone-colored, glazed, terra-cotta façade Official Building Name Woolworth Building Location 233 Broadway, New York City, NY Construction Start - 1910 | Completion- 1913 History Tallest building in the World 1913 - 1930 Named the “Cathedral of Commerce” upon completion Construction Cost $13.5 million LEADERSHIP | PROJECT TEAM | DESIGN | CONSTRUCTION U.S. President Woodrow Wilson New York City Mayor William Jay Gaynor Building Owner 1913 F.W. Woolworth Company Developer F.W. Woolworth Company & Irving National Exchange Bank Architect Cass Gilbert Structural Engineering Gunvald Aus Company Primary Contractor Thompson-Starrett & Company Current Use Office | Residential (top 30 floors) BUILDING CONSTRUCTION & AMENITIES SUMMARY Size 1.3 Million GSF Height 792 Feet | 241 Meters Number of Floors 57 (above ground) Design 57 floor, Neo-Gothic architectural style, featuring gargoyles, arches and flying buttresses. -

True to the City's Teeming Nature, a New Breed of Multi-Family High Rises

BY MEI ANNE FOO MAY 14, 2016 True to the city’s teeming nature, a new breed of multi-family high rises is fast cropping up around New York – changing the face of this famous urban jungle forever. New York will always be known as the land of many towers. From early iconic Art Deco splendours such as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, to the newest symbol of resilience found in the One World Trade Center, there is no other city that can top the Big Apple’s supreme skyline. Except itself. Tall projects have been proposed and built in sizeable numbers over recent years. The unprecedented boom has been mostly marked by a rise in tall luxury residential constructions, where prior to the completion of One57 in 2014, there were less than a handful of super-tall skyscrapers in New York. Now, there are four being developed along the same street as One57 alone. Billionaire.com picks the city’s most outstanding multi-family high rises on the concrete horizon. 111 Murray Street This luxury residential tower developed by Fisher Brothers and Witkoff will soon soar some 800ft above Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood. Renderings of the condominium showcase a curved rectangular silhouette that looks almost round, slightly unfolding at the highest floors like a flared glass. The modern design is from Kohn Pedersen Fox. An A-team of visionaries has also been roped in for the project, including David Mann for it residence interiors; David Rockwell for amenities and public spaces and Edmund Hollander for landscape architecture. -

Innovative Structural Concept & Solution for Mega Tall Buildings

Open Access Library Journal 2017, Volume 4, e3459 ISSN Online: 2333-9721 ISSN Print: 2333-9705 Innovative Structural Concept & Solution for Mega Tall Buildings Applied to One Kilometer Skyscraper Feroz Alam Civil Engineering, The Institute of Engineers, Dhaka, Bangladesh How to cite this paper: Alam, F. (2017) Abstract Innovative Structural Concept & Solution for Mega Tall Buildings Applied to One Ki- Structural systems for tall buildings have undergone dramatic changes since lometer Skyscraper. Open Access Library the demise of the conventional rigid frames in the 1960s as the predominant Journal, 4: e3459. type of structural system for steel or concrete tall buildings. Generally, the https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1103459 structural systems of tall buildings are considered to be two types. One is inte- Received: February 16, 2017 rior and the other one is exterior type. The frame tube buildings have been the Accepted: April 14, 2017 most efficient structural system used for building which is in the range of 40 - Published: April 17, 2017 100 stories. In the early 1970s, Fintel (1974) indicated that properly designed Copyright © 2017 by author and Open structural walls could be used effectively as the primary lateral-load resisting Access Library Inc. system for both wind and earthquake loading in multistory buildings. This This work is licensed under the Creative study is intended to model an advanced structural system for tall buildings. In Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). this innovative concept, several parallel shear walls have been arranged in http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ both directions and connected with beams and R.C. -

The Skyscraper of the 1920S

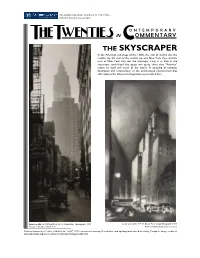

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y IN OMMENTARY HE WENTIES T T C * THE SKYSCRAPER In the American self-image of the 1920s, the icon of modern was the modern city, the icon of the modern city was New York City, and the icon of New York City was the skyscraper. Love it or hate it, the skyscraper symbolized the go-go and up-up drive that “America” meant to itself and much of the world. A sampling of twenties illustration and commentary on the architectural phenomenon that still captures the American imagination is presented here. Berenice Abbott, Cliff and Ferry Street, Manhattan, photograph, 1935 Louis Lozowick, 57th St. [New York City], lithograph, 1929 Museum of the City of New York Renwick Gallery/Smithsonian Institution * ® National Humanities Center, AMERICA IN CLASS , 2012: americainclass.org/. Punctuation and spelling modernized for clarity. Complete image credits at americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/imagecredits.htm. R. L. Duffus Robert L. Duffus was a novelist, literary critic, and essayist with New York newspapers. “The Vertical City” The New Republic One of the intangible satisfactions which a New Yorker receives as a reward July 3, 1929 for living in a most uncomfortable city arises from the monumental character of his artificial scenery. Skyscrapers are undoubtedly popular with the man of the street. He watches them with tender, if somewhat fearsome, interest from the moment the hole is dug until the last Gothic waterspout is put in place. Perhaps the nearest a New Yorker ever comes to civic pride is when he contemplates the skyline and realizes that there is and has been nothing to match it in the world. -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

The Case of New York City's Financial District

INFORMATION TECHNOWGY AND WORLD CITY RESTRUCTURING: THE CASE OF NEW YORK CITY'S FINANCIAL DISTRICT by Travis R. Longcore A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Bachelor of Arts in Geography May 1993 Copyright 1993 Travis R. Longcore All Rights Reserved INFORMATION TECHNOWGY AND WORLD CITY RESTRUCTURING: THE CASE OF NEW YORK CITY'S FINANCIAL DISTRICT by Travis R. Longcore Approved: Peter W. Rees, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: Robert Warren, Ph.D. Committee Member from the College of Urban Affairs Approved: Francis X. Tannian, Ph.D. Committee Member from the University Honors Program Approved: Robert F. Brown, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program "Staccato signals of constant information, A loose affiliation of millionaires and billionaires and baby, These are the days of miracle and wonder. This is a long distance call. " Paul Simon, Graceland iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to recognize and thank Dr. Peter Rees for his guidance on this project. Without the patient hours of discussion, insightful editorial comments, and firm schedule, this thesis would have never reached completion. The author also thanks the University Honors Program, the Undergraduate Research Program and the Department of Geography at the University of Delaware for their financial support. Many thanks are due to the Water Resources Agency for New Castle County for the use of their automated mapping system. IV TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OFTABLES .................................... viii LIST OF FIGURES ix ABSTRACT ....................................... .. x Chapter 1 THE CITY IN A WORLD ECONOMY ................... -

Chrysler Building: Race to the Sky

PDHonline Course S255 (4 PDH) Chrysler Building: Race to the Sky Instructor: Jeffrey Syken 2012 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider Race to the Sky 1 Table of Contents Slide/s Part Title/Description 1 N/A Title 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~22 1 THE 1925 PARIS EXPOSITION 23~53 2 ART DECO 54~111 3 EVER HIGHER 112~157 4 RACE FOR THE SKY 158~177 5 OLD BULLET HEAD 178~234 6 THE DESIGN 235~252 7 THE LOBBY 253~262 8 THE CLOUD CLUB 263~273 9 CONSTRUCTION 274~300 10 LEGACY 2 Part 1 THE 1925 PARIS EXPOSITION 3 Away with the architraves, pillars and antiquated temples of the aristocratic past. The universal human community will produce its own style, appropriate for its own age here in the twentieth century! 4 5 6 “French taste was law… Why? Because all around us the English, Germans, Belgians, Italians, Scandinavians and even the Americans themselves reacted and sought to create for themselves – for better or worse – an original art, a novel style corresponding to the changing needs manifested by an international clientele…” Lucien Dior – French Minister of Commerce 7 8 9 10 “All that clearly distinguished the older ways of life was rigorously excluded from the exposition of 1925” Waldemar George 11 12 13 “A cabinet maker is an architect…In designing a piece of furniture, it is essential to study conscientiously the balance of volume, the silhouette and the proportion in accordance with the chosen material and the technique imposed by this material” RE: Excerpt from: Arts Decoratifs: A Personal Recollection of the Paris Exhibition 14 15 “In 1900, we saw the triumph of noodling ornamentation. -

Bfm:978-1-56898-652-4/1.Pdf

Manhattan Skyscrapers Manhattan Skyscrapers REVISED AND EXPANDED EDITION Eric P. Nash PHOTOGRAPHS BY Norman McGrath INTRODUCTION BY Carol Willis PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY Princeton Architectural Press 37 East 7th Street New York, NY 10003 For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657 Visit our website at www.papress.com © 2005 Princeton Architectural Press All rights reserved Printed and bound in China 08 07 06 05 4 3 2 1 No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. The publisher gratefully acknowledges all of the individuals and organizations that provided photographs for this publi- cation. Every effort has been made to contact the owners of copyright for the photographs herein. Any omissions will be corrected in subsequent printings. FIRST EDITION DESIGNER: Sara E. Stemen PROJECT EDITOR: Beth Harrison PHOTO RESEARCHERS: Eugenia Bell and Beth Harrison REVISED AND UPDATED EDITION PROJECT EDITOR: Clare Jacobson ASSISTANTS: John McGill, Lauren Nelson, and Dorothy Ball SPECIAL THANKS TO: Nettie Aljian, Nicola Bednarek, Janet Behning, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Jan Haux, Clare Jacobson, John King, Mark Lamster, Nancy Eklund Later, Linda Lee, Katharine Myers, Jane Sheinman, Scott Tennent, Jennifer Thompson, Paul G. Wagner, Joe Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press —Kevin Lippert, Publisher LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Nash, Eric Peter. Manhattan skyscrapers / Eric P. Nash ; photographs by Norman McGrath ; introduction by Carol Willis.—Rev. and expanded ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56898-545-2 (alk. -

Fractious Firsts Carol Willis, Founding Director, the Skyscraper Museum the Tallest Building in the World Today, the 828-Meter B

Fractious Firsts Carol Willis, Founding Director, The Skyscraper Museum The tallest building in the world today, the 828-meter Burj Khalifa, as well as the one perhaps on its way to 1,000-meter height, Jeddah Tower, are bearing-wall structures – much like the first and tallest of New York’s early skyscrapers, the 1874 Tribune Tower. Thick walls (either of 19th-century brick and stone or 21st-century reinforced concrete) hold up these buildings – not a skeleton of steel, the major material and method of skyscraper construction for most of the 20th century. When the CTBUH organized the October 2019 conference “First Skyscrapers/ Skyscraper Firsts,” they fell victim to confirmation bias*. Implicit in the call for papers was a definition of “skyscraper” as a tall building constructed of steel. This was made clear in the initial emphasis on Chicago’s Home Insurance Building as the putative “first skyscraper.” When the steering committee adamantly rejected the proposal that vying presenters debate the priority of a single building in the history of the type, the conference title was adjusted to the plural: First Skyscrapers/ Skyscraper Firsts. This conceptualization is still a problem. The idea of a “first’ in the evolution of a building type that evolved from so many simultaneous forces and factors is unsound. Advances in technologies – whether the metal skeleton, passenger elevators in office buildings, or curtain walls – represent one aspect in the fairly sudden appearance of buildings of nine or ten stories in the early 1870s. But also key were the dynamics of urbanization – cities’ burgeoning populations and competition for expensive land and prime locations. -

94 GREENWICH STREET HOUSE, 94 Greenwich Street (Aka 14-18 Rector Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 23, 2009, Designation List 414 LP-2218 94 GREENWICH STREET HOUSE, 94 Greenwich Street (aka 14-18 Rector Street), Manhattan. Built c. 1799-1800; fourth story added by 1858; rear addition c. 1853/1873. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 53, Lot 41. On January 30, 2007, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the 94 Greenwich Street House and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 1). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twelve people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, Municipal Art Society of New York, New York Landmarks Conservancy, and Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received a number of communications in support of designation, including a letter from Augustine Hicks Lawrence III, a sixth-generation descendant of the original owner. One of the property’s owners, who oppose designation, appeared at the June 23, 2009, public meeting and requested a postponement of the vote. The building had been previously heard by the Commission on October 19, 1965, and June 23, 1970 (LP-0049). Summary The Federal style rowhouse at No. 94 Greenwich Street in Lower Manhattan was constructed c.1799-1800 as an investment property, right after this block was created through landfill and Greenwich and Rector Streets had been laid out. At the time, this was the most fashionable neighborhood for New York’s social elite and wealthy merchant class.