At Home with Durga: the Goddess in a Palace and Corporeal Identity in Rituparno Ghosh’S Utsab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18Th and 19Th Centuries): Historical Perspective

Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Session: 2008-09 Academic Supervisor Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History University of Dhaka This Thesis Submitted to the Department of History University of Dhaka for the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M.Phil) December, 2013 Declaration This is to certify that Murshida Bintey Rahman has written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ under my supervision. She has written the thesis for the M.Phil degree in History. I further affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Dr. Sharif uddin Ahmed Supernumerary Professor Department of History Dated: University of Dhaka 2 Declaration I do declare that, I have written the thesis titled ‘Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th & 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective’ for the M.Phil degree in History. I affirm that the work reported in this thesis is original and no part or the whole of the dissertation has been submitted to, any form in any other University or institution for any degree. Murshida Bintey Rahman Registration No: 45 Dated: Session: 2008-09 Department of History University of Dhaka 3 Banians in the Bengal Economy (18th and 19th Centuries): Historical Perspective Abstract Banians or merchants’ bankers were the first Bengali collaborators or cross cultural brokers for the foreign merchants from the seventeenth century until well into the mid-nineteenth century Bengal. -

Revised Master Plan and Zoning Regulations for Greater Tezpur -2031

REVISED MASTER PLAN AND ZONING REGULATIONS FOR GREATER TEZPUR -2031 PREPARED BY DISTRICT OFFICE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM TEZPUR: ASSAM SCHEDULE a) Situation of the Area : District : Sonitpur Sub Division : Tezpur Area : 12,659Hect. Or 126.60 Sq Km. TOWN & VILLAGES INCLUDED IN THE REVISED MASTER PLAN AREA FOR GREATER TEZPUR – 2031 MOUZA TOWN & VILLAGES Mahabhairab Tezpur Town & 1. Kalibarichuk, 2. Balichapari, 3. Barikachuburi, 4. Hazarapar Dekargaon, 5. Batamari, 6. Bhojkhowa Chapari, 7. Bhojkhowa Gaon, 8. Rajbharal, 9. Bhomoraguri Pahar, 10. Jorgarh, 11. Karaiyani Bengali, 12. Morisuti, 13. Chatai Chapari, 14. Kacharipam, 15. Bhomoraguri Gaon, 16. Purani Alimur, 17. Uriamguri, 18. Alichinga Uriamguri. Bhairabpad 19. Mazgaon, 20. Dekargaon, 21. Da-parbatia, 22. Parbatia, 23. Deurigaon, 24. Da-ati gaon, 25. Da-gaon pukhuria, 26. Bamun Chuburi, 27. Vitarsuti, 28. Khanamukh, 29. Dolabari No.1, 30. Dolabari No.2, 31. Gotlong, 32. Jahajghat 33. Kataki chuburi, 34. Sopora Chuburi, 35. Bebejia, 36. Kumar Gaon. Halleswar 37. Saikiachuburi Dekargaon, 38. Harigaon, 39. Puthikhati, 40. Dekachuburi Kundarbari, 41. Parowa gaon, 42. Parowa TE, 43. Saikia Chuburi Teleria, 44. Dipota Hatkhola, 45. Udmari Barjhar, 46. Nij Halleswar, 47. Halleswar Devalaya, 48. Betonijhar, 49. Goroimari Borpukhuri, 50. Na-pam, 51. Amolapam, 52. Borguri, 53. Gatonga Kahdol, 54. Dihingia Gaon, 55. Bhitar Parowa, 56. Paramaighuli, 57. Solmara, 58. Rupkuria, 59. Baghchung, 60. Kasakani, 61. Ahatguri, 62. Puniani Gaon, 63. Salanigaon, 64. Jagalani. Goroimari 65. Goroimari Gaon, 66. Goroimari RF 1 CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION Tezpur town is the administrative H/Q of Sonitpur Dist. Over the years this town has emerged as on the few major important urban centers of Assam & the North Eastern Region of India. -

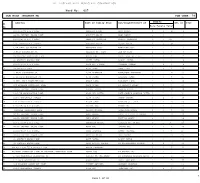

Ward No: 027 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 027 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 123/2/H/69 A P C ROAD ABHIJIT KUNDU BASU KUNDU 5 4 9 1 2 44/3A HARTAKI BAGAN LANE ABHIJIT MARIK AMAL MARIK 4 3 7 2 3 123/2/H/34 A P C ROAD ABHIJIT PRAMANIK PRADIP PRAMANIK 6 5 10+ 3 4 124/3 MANIKTALA STREET ABHISEK BARIK ASHOK BARIK 6 3 9 4 5 1/2A RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. ABHISHEK GOUD BABLURAM GOUD 4 1 5 5 6 3 RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. ABINASH KR. SHAW DEB KR SHAW 2 4 6 6 7 2A BASHNAB SAMMILANI LANE ADHIR DAS LATE DULAL CH. DAS 1 2 3 7 8 45 HARTAKI BAGAN LANE ADITI PATRA ASHOK PATRA 2 3 5 8 9 123/2/H/48 A P C ROAD AJAY KR. SONKAR SITARAM SONKAR 4 2 6 9 10 2A BARRICK LANE AJAY SHAW RAMA SHAW 2 4 6 10 11 3 RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. AJIT KARMAKAR RAMESHWAR KARMAKAR 3 1 4 12 12 1/2A RAJA GOPIMOHAN ST. AJIT SINGH LACHHMI SINGH 3 3 6 13 13 9 REV. KALI BANERJEE ROW AKASH LAHA BONOMALI LAHA 2 1 3 14 14 2/A BASHNAB SAMMILANI LANE ALAK NAYEK LT PRADYUT NAYEK 1 4 5 15 15 44/3A HARTAKI BAGAN LANE ALHADI PATRA SWAPAN PATRA 4 2 6 16 16 19/1/1B MADAN MITRA LANE ALOK DEY DUTTA LATE GANESH CHANDRA DUTTA 1 1 2 17 17 124/2 MANIKTALA STREET ALOK SANTRA SAMAR SANTRA 2 2 4 19 18 124/2 MANIKTALA STREET ALOKA SAHA NARAYAN CH. -

Jorasanko Assembly Constituency Total Polling Stations K.M.C

List of Polling Premises under 165 – Jorasanko Assembly Constituency Total Polling Stations K.M.C. Borough Police Sl. Name & Address of the Polling Premises Polling Attached Ward No No. Station Stations Shree Maheswari Vidyalaya, 4, Sovaram 1 8, 9, 11, 14, 16, 19 6 22 IV Posta Basak Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Nawal Kishore Daga Bikaner Walas 2 Dharmshala, 41, Kali Krishna Tagore Street, 1, 2, 3, 17 4 22 IV Posta Kolkata – 700 007 Maheshwari Balika Vidyalaya, 4, Sovaram 3 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 18 6 22 IV Posta Basak Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Phulchand Mukimchand Jain Dharmasala, P- 4 4, 10, 22, 25 4 22 IV Posta 37 Kalakar Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Mukram Kanodia C. P. Model School, 9 Bartala 5 15, 20, 21 3 22 IV Posta Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Marwari Balika Vidyalaya, 29 Banstala Gulee, 23, 24, 36, 37, 40, 6 9 23 IV Posta Kolkata - 700 007 41, 43, 44, 45 Shree Didoo Maheswari Panchayat Vidyalaya 26, 31, 32, 33, 34, 7 8 23 IV Posta 259, Rabindra Sarani, Kolkata - 700 007 38, 39, 42 K.M.C.P. School, 15 Shibtala Street, Kolkata - 8 27, 28, 29, 30, 35 5 23 IV Posta 700 007 Nopany High, 2C, Nando Mullick Lane, Kolkata - 9 46, 47, 48, 49 4 25 IV Girish Park 700 006 Singhee Bagan High School for Girls, 7 10 50, 51, 52, 53 4 25 IV Girish Park Rajendra Mullick Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Rabindra Bharati University (Jorasanko 54, 55, 56, 63, 64, 11 Campus), 6/4 Dwarkanath Tagore Lane, 6 25 IV Girish Park 65 Kolkata - 700 007 Friend's United Club (Girish Park), 213B 12 58, 59 2 25 IV Girish Park Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata - 700 006 Peary Charan Girls High School, 146B Tarak 13 61, 62, 66, 67, 71 5 25 IV Girish Park Pramanick Road, Kolkata - 700 006 Goenka Hospital Building, 145 Muktaram Babu 14 57, 79, 80 3 25 IV Girish Park Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Sri Ram Narayan Singh Memorial High School, 15 68, 69 2 25 IV Girish Park 10 Dr. -

An Exploration of Hindu Goddess Iconography Evyn Venkateswaran

Venkateswaran 1 Devi: An Exploration of Hindu Goddess Iconography Evyn Venkateswaran ‘Devi’ is a collection of illustrations that emphasize the unifying feminine power in Hinduism, commonly known as shakti. Portrayed within are several deities that have unique stories and corporeal forms, re-contextualized through a modern lens. The ways in which I have achieved this is through my depiction of each of the goddesses, featuring a separate culture or ethnicity found within the Indian Subcontinent. This challenges the current market of Hindu illustrations where all goddesses share the same facial-features, skin-tone, and clothing. In addition, each of the artworks contain compositions that are unique and break away from the typical forward-facing, subject gazing directly at the audience compositions found in the aforementioned illustrations. Lastly, when creating my illustrations, I strove to capture a story or a meaning that would distinguish the identity of that specific deity. Initially, the technique in which I completed this project was through using either oil pastels or nupastels, later adding a layer of digital paint with Photoshop. However, due to different situational changes, I have finished my last images utilizing Procreate on my iPad Pro. With both situations, I focused on impressionistic mark-making, using several colors to create an iridescent quality in each of the pieces. Within my color palettes, I used golden-yellow in each of the pieces to draw significance between the goddesses, for example using the most amount of gold in Durga to emphasize how she’s the ultimate form of shakti. My intent of displaying these images is through posters that can either be used as iconography within worship or hung up as decoration. -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Premendra Mitra - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Premendra Mitra - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Premendra Mitra(1904 - 3 May 1988) Premendra Mitra was a renowned Bengali poet, novelist, short story writer and film director. He was also an author of Bangla science fiction and thrillers. <b>Life</b> He was born in Varanasi, India, though his ancestors lived at Rajpur, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. His father was an employee of the Indian Railways and because of that; he had the opportunity of travelling to many places in India. He spent his childhood in Uttar Pradesh and his later life in Kolkata & Dhaka. He was a student of South Suburban School (Main) and later at the Scottish Church College in Kolkata. During his initial years, he (unsuccessfully) aspired to be a physician and studied the natural sciences. Later he started out as a school teacher. He even tried to make a career for himself as a businessman, but he was unsuccessful in that venture as well. At a time, he was working in the marketing division of a medicine producing company. After trying out the other occupations, in which he met marginal or moderate success, he rediscovered his talents for creativity in writing and eventually became a Bengali author and poet. Married to Beena Mitra, he was, by profession, a Bengali professor at City College in north Kolkata. He spent almost his entire life in a house at Kalighat, Kolkata. <b>As an Author & Editor</b> In November 1923, Mitra came from Dhaka, Bangladesh and stayed in a mess at Gobinda Ghoshal Lane, Kolkata. -

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga

Orissa Review * October - 2004 The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga Pradeep Kumar Gan Shaktism, the cult of Mother Goddess and vast mass of Indian population, Goddess Durga Shakti, the female divinity in Indian religion gradually became the supreme object of 5 symbolises form, energy or manifestation of adoration among the followers of Shaktism. the human spirit in all its rich and exuberant Studies on various aspects of her character in variety. Shakti, in scientific terms energy or our mythology, religion, etc., grew in bulk and power, is the one without which no leaf can her visual representation is well depicted in stir in the world, no work can be done without our art and sculpture. It is interesting to note 1 it. The Goddess has been worshipped in India that the very origin of her such incarnation (as from prehistoric times, for strong evidence of Durga) is mainly due to her celestial mount a cult of the mother has been unearthed at the (vehicle or vahana) lion. This lion is usually pre-vedic civilization of the Indus valley. assorted with her in our literature, art sculpture, 2 According to John Marshall Shakti Cult in etc. But it is unfortunate that in our earlier works India was originated out of the Mother Goddess the lion could not get his rightful place as he and was closely associated with the cult of deserved. Siva. Saivism and Shaktism were the official In the Hindu Pantheon all the deities are religions of the Indus people who practised associated in mythology and art with an animal various facets of Tantra. -

Shuktara October 2014 the Major Festival of Durga Puja Is Now Over

shuktara a new home in the world for young adults 43b/5 Narayan Roy Road P.S. Thakurpukur Kolkata 700008 West Bengal INDIA Contact no: - 91 33 2496 0051 October 2014 The major festival of Durga Puja is now over and by the time you read this, Diwali will also have come and gone. Diwali is celebrated in most of India, but here in West Bengal we celebrate Kali Puja. This is the night when Bengalis let off their fireworks, light candles and an evening that everyone at shuktara really enjoys. Because Diwali is usually the following day, they use this excuse and have two nights of fireworks! However this year, both festivals fall on the same day – but I expect they will keep some fireworks back anyway and celebrate for a couple of nights running. As with the Pujas, I usually hide away somewhere quietly! The Durga Puja festivities were enjoyed by everyone at shuktara. Some of the older boys went out on their own, some stayed at home and some of them went with Pappu to help carry Prity and our new girl Moni around the city. They always hire a big car for this occasion and stay out all night long. Sanjay Sarkar – Durga Puja 2014 Moni on 10th September 2014 Moni had come a short time before the Pujas and was very excited to have new clothes and jewellery to wear for her very first outing. At the beginning of September, Pappu had received a phone call from Childline India Foundation about a little girl who they were unable to care for. -

The Hooghly River a Sacred and Secular Waterway

Water and Asia The Hooghly River A Sacred and Secular Waterway By Robert Ivermee (Above) Dakshineswar Kali Temple near Kolkata, on the (Left) Detail from The Descent of the Ganga, life-size carved eastern bank of the Hooghly River. Source: Wikimedia Commons, rock relief at Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. Source: by Asis K. Chatt, at https://tinyurl.com/y9e87l6u. Wikimedia Commons, by Ssriram mt, at https://tinyurl.com/y8jspxmp. he Hooghly weaves through the Indi- Hooghly was venerated as the Ganges’s original an state of West Bengal from the Gan- and most sacred route. Its alternative name— ges, its parent river, to the sea. At just the Bhagirathi—evokes its divine origin and the T460 kilometers (approximately 286 miles), its earthly ruler responsible for its descent. Hindus length is modest in comparison with great from across India established temples on the Asian rivers like the Yangtze in China or the river’s banks, often at its confluence with oth- Ganges itself. Nevertheless, through history, er waterways, and used the river water in their the Hooghly has been a waterway of tremen- ceremonies. Many of the temples became fa- dous sacred and secular significance. mous pilgrimage sites. Until the seventeenth century, when the From prehistoric times, the Hooghly at- main course of the Ganges shifted decisively tracted people for secular as well as sacred eastward, the Hooghly was the major channel reasons. The lands on both sides of the river through which the Ganges entered the Bay of were extremely fertile. Archaeological evi- Bengal. From its source in the high Himalayas, dence confirms that rice farming communi- the Ganges flowed in a broadly southeasterly ties, probably from the Himalayas and Indian direction across the Indian plains before de- The Hooghly was venerated plains, first settled there some 3,000 years ago.