Turkish Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Big World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema

Markets, Globalization & Development Review Volume 2 Article 8 Number 2 Popular Culture and Markets in Turkey 2017 The iB g World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema Andreas Treske Bilkent University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Treske, Andreas (2017) "The iB g World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema," Markets, Globalization & Development Review: Vol. 2: No. 2, Article 8. DOI: 10.23860/MGDR-2017-02-02-08 Available at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol2/iss2/8http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol2/iss2/8 This Media Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Markets, Globalization & Development Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This media review is available in Markets, Globalization & Development Review: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol2/iss2/8 The iB g World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema Andreas Treske Abstract Reha Erdem’s latest film Big Big World (Koca Dünya) was selected for the “Horizons” (“Orizzonti”) section at the 73rd Venice International Film Festival in 2016 and won a prestigious special jury award. The eV nice selection is standing for a tendency to hold on, and celebrate the so-called “World Cinema” along with Hollywood blockbusters and new experimental arthouse films in a festival programming mix, insisting to stop for a moment in time a cinema that is already on the move. -

Antiochia As a Cinematic Space and Semir Aslanyürek As a Film Director from Antiochia

Antiochia As A Cinematic Space and Semir Aslanyürek as a Film Director From Antiochia Selma Köksal, Düzce University, [email protected] Volume 8.2 (2020) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2020.279 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract This study will look at cinematic representation of Antiochia, a city with multiple identities, with a multi- cultural, long and deep historical background in Turkish director Semir Aslanyürek’s films. The article will focus on Aslanyürek’s visual storytelling through his beloved city, his main characters and his main conflicts and themes in his films Şellale (2001), Pathto House (2006), 7 Yards (2009), Lal (2013), Chaos (2018). Semir Aslanyürek was born in Antiochia in 1956. After completing his primary and secondary education in Antiochia (Hatay), he went to Damascus and began his medical training. As an amateur sculptor, he won an education scholarship with one of his statues for art education in Moscow. After a year, he decided to study on cinema instead of art. Semir Aslanyürek studied Acting, Cinema and TV Film from 1980 to 1986 in the Russian State University of Cinematography (VGIK), Faculty of Film Management, and took master's degree. While working as a professor at Marmara University, Aslanyürek directed feature films and wrote many screenplays. This article will also base its arguments on Aslanyürek's cinematic vision as multi-cultural and as a multi- disciplinary visual artist. Keywords: Antiochia; cinematic space; blind; speechless; war; ethnic conflicts; Semir Aslanyürek New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. -

Cinema and Politics

Cinema and Politics Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and The New Europe Edited by Deniz Bayrakdar Assistant Editors Aslı Kotaman and Ahu Samav Uğursoy Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and The New Europe, Edited by Deniz Bayrakdar Assistant Editors Aslı Kotaman and Ahu Samav Uğursoy This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2009 by Deniz Bayrakdar and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0343-X, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0343-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Images and Tables ......................................................................... viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Introduction ............................................................................................. xvii ‘Son of Turks’ claim: ‘I’m a child of European Cinema’ Deniz Bayrakdar Part I: Politics of Text and Image Chapter One ................................................................................................ -

Three Monkeys

THREE MONKEYS (Üç Maymun) Directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan Winner Best Director Prize, Cannes 2008 Turkey / France/ Italy 2008 / 109 minutes / Scope Certificate: 15 new wave films Three Monkeys Director : Nuri Bilge Ceylan Producer : Zeynep Özbatur Co-producers: Fabienne Vonier Valerio De Paolis Cemal Noyan Nuri Bilge Ceylan Scriptwriters : Ebru Ceylan Ercan Kesal Nuri Bilge Ceylan Director of Photography : Gökhan Tiryaki Editors : Ayhan Ergürsel Bora Gökşingöl Nuri Bilge Ceylan Art Director : Ebru Ceylan Sound Engineer : Murat Şenürkmez Sound Editor : Umut Şenyol Sound Mixer : Olivier Goinard Production Coordination : Arda Topaloglu ZEYNOFILM - NBC FILM - PYRAMIDE PRODUCTIONS - BIM DISTRIBUZIONE In association with IMAJ With the participation of Ministry of Culture and Tourism Eurimages CNC COLOUR – 109 MINUTES - HD - 35mm - DOLBY SR SRD - CINEMASCOPE TURKEY / FRANCE / ITALY new wave films Three Monkeys CAST Yavuz Bingöl Eyüp Hatice Aslan Hacer Ahmet Rıfat Şungar İsmail Ercan Kesal Servet Cafer Köse Bayram Gürkan Aydın The child SYNOPSIS Eyüp takes the blame for his politician boss, Servet, after a hit and run accident. In return, he accepts a pay-off from his boss, believing it will make life for his wife and teenage son more secure. But whilst Eyüp is in prison, his son falls into bad company. Wanting to help her son, Eyüp’s wife Hacer approaches Servet for an advance, and soon gets more involved with him than she bargained for. When Eyüp returns from prison the pressure amongst the four characters reaches its climax. new wave films Three Monkeys Since the beginning of my early youth, what has most intrigued, perplexed and at the same time scared me, has been the realization of the incredibly wide scope of what goes on in the human psyche. -

REHA ERDEM FİLMLERİNDE “ERKEKLİK” ARKETİPLERİNİN YENİDEN ÜRETİMİ REPRODUCTION of the “MASCULINITY” ARCHETYPES in REHA ERDEM FILMS İlknur GÜRSES * Rifat BECERİKLİ **

Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi The Journal of International Social Research Cilt: 9 Sayı: 42 Volume: 9 Issue: 42 Şubat 2016 February 2016 www.sosyalarastirmalar.com Issn: 1307-9581 REHA ERDEM FİLMLERİNDE “ERKEKLİK” ARKETİPLERİNİN YENİDEN ÜRETİMİ REPRODUCTION OF THE “MASCULINITY” ARCHETYPES IN REHA ERDEM FILMS İlknur GÜRSES * Rifat BECERİKLİ ** Öz Arketipler, Jung’un tanımladığı hali ile kolektif bilinçdışımızda hareket halinde olan, dolaylı ya da doğrudan gündelik hayatlarımızı/bilincimizi yönlendiren arkaik imgelerdir. Freud’un bilinçaltı kavramından farklı olarak, kolektif bilinçdışı kişinin içinde hareket ettiği toplumun kültürel geçmişini ve kültürün ilişkiye geçtiği diğer tüm tarihsel bilişsel birikimi kapsamaktadır. Arketipler, kişilerden bağımsız ancak hayatlarına etki eden insanlık tarihinin kültürel yapıtaşlarındandır. Arketipler aracılığıyla kimliklerin, olguların nasıl bir yol izlediğini ve nelerin dönüştüğünü belirli kavramlarla incelemek mümkündür. Çalışmada, Reha Erdem’in yönettiği A Ay (1988), Kaç Para Kaç (1999), Korkuyorum Anne (2004), Beş Vakit (2006), Hayat Var (2008), Kosmos (2010), Jin (2013), Şarkı Söyleyen Kadınlar (2014) adlı filmlerindeki ana erkek karakterlerin öyküleri, erkeklik arketipleri bağlamında Jungçu bir yaklaşımla karakterlerin anlatı içerisindeki dönüşümleri doğrultusunda incelenecektir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Arketip, Sinema, Reha Erdem, Auteur, Erkeklik. Abstract Archetypes as Jung described, archaic images which are leading our lives directly or indirectly and continously moving in out collective unconsciousness. Apart from the Freud’s subconscious concept, collective unconsciousness covers the cultural history of the individuals live in and the whole cognitive accumulation which culture interacts. Archetypes are independent from the people but cultural milestones of history affect the people lives. With the help of the archetypes, it is possible to analyze through some terms that what kind of a way followed by the identities and facts and which are transformed. -

The Space Between: a Panorama of Cinema in Turkey

THE SPACE BETWEEN: A PANORAMA OF CINEMA IN TURKEY FILM LIST “The Space Between: A Panorama of Cinema in Turkey” will take place at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center from April 27 – May 10, 2012. Please note this list is subject to change. AĞIT a week. Subsequently, Zebercet begins an impatient vigil Muhtar (Ali Şen), a member of the town council, sells a piece and, when she does not return, descends into a psychopathic of land in front of his home to Haceli (Erol Taş), a land ELEGY breakdown. dispute arises between the two families and questions of Yılmaz Güney, 1971. Color. 80 min. social and moral justice come into play. In Ağıt, Yılmaz Güney stars as Çobanoğlu, one of four KOSMOS smugglers living in a desolate region of eastern Turkey. Reha Erdem, 2009. Color. 122 min. SELVİ BOYLUM, AL YAZMALIM Greed, murder and betrayal are part of the everyday life of THE GIRL WITH THE RED SCARF these men, whose violence sharply contrasts with the quiet Kosmos, Reha Erdem’s utopian vision of a man, is a thief who Atıf Yılmaz, 1977. Color. 90 min. determination of a woman doctor (Sermin Hürmeriç) who works miracles. He appears one morning in the snowy border attends to the impoverished villagers living under constant village of Kars, where he is welcomed with open arms after Inspired by the novel by Kyrgyz writer Cengiz Aytmatov, Selvi threat of avalanche from the rocky, eroded landscape. saving a young boy’s life. Despite Kosmos’s curing the ill and Boylum, Al Yazmalım tells the love story of İlyas (Kadir İnanır), performing other miracles, the town begins to turn against a truck driver from Istanbul, his new wife Asya (Türkan Şoray) him when it is learned he has fallen in love with a local girl. -

Female Silences, Turkey's Crises

Female Silences, Turkey’s Crises Female Silences, Turkey’s Crises: Gender, Nation and Past in the New Cinema of Turkey By Özlem Güçlü Female Silences, Turkey’s Crises: Gender, Nation and Past in the New Cinema of Turkey By Özlem Güçlü This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Özlem Güçlü All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9436-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9436-4 To Serhan Şeşen (1982-2008) and Onur Bayraktar (1979-2010) TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .......................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... ix Notes on Translations ................................................................................. xi Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 And Silence Enters the Scene Chapter One ............................................................................................... 30 New Cinema of Turkey and the Novelty of Silence Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

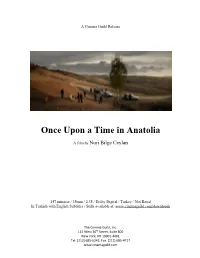

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

A Cinema Guild Release Once Upon a Time in Anatolia A film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan 157 minutes / 35mm / 2.35 / Dolby Digital / Turkey / Not Rated In Turkish with English Subtitles / Stills available at: www.cinemaguild.com/downloads The Cinema Guild, Inc. 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800 New York, NY 10001‐4061 Tel: (212) 685‐6242, Fax: (212) 685‐4717 www.cinemaguild.com Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Synopsis Late one night, an array of men- a police commissioner, a prosecutor, a doctor, a murder suspect and others- pack themselves into three cars and drive through the endless Anatolian country side, searching for a body across serpentine roads and rolling hills. The suspect claims he was drunk and can’t quite remember where the body was buried; field after field, they dig but discover only dirt. As the night draws on, tensions escalate, and individual stories slowly emerge from the weary small talk of the men. Nothing here is simple, and when the body is found, the real questions begin. At once epic and intimate, Ceylan’s latest explores the twisted web of truth, and the occasional kindness of lies. About the Film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia was the recipient of the Grand Prix at the Cannes film festival in 2011. It was an official selection of New York Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Biography: Born in Bakırköy, Istanbul on 26 January 1959, Nuri Bilge Ceylan spent his childhood in Yenice, his father's hometown in the North Aegean province of Çanakkale. -

New Turkish Cinema – Some Remarks on the Homesickness of the Turkish Soul

New Turkish Cinema – Some Remarks on the Homesickness of the Turkish Soul Agnieszka Ayşen KAIM, University of Lodz, [email protected] Abstract Contemporary cinematography reflects the dualism in modern Turkish society. The heart of every inhabitant of Anatolia is dominated by homesickness for his little homeland. This overpowering feeling affects common people migrating in search of work as well as intellectuals for whom Istanbul is a place for their artistic development but not the place of origin. The city and “the rest” have been considered in opposition to each other. The struggle between “the provincial” and “the urban” has even created its own film genre in Turkish cinematography described as “homeland movies”. They paint the portrait of a Turkish middle class intellectual on the horns of a dilemma, the search for a modern identity and a place to belong in a modern world where values are constantly shifting. Special Issue: 1 (2011) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2011.23 | http://cinej.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. New Turkish Cinema – Some Remarks on the Homesickness of the Turkish Soul For decades „It„s like a Turkish film” has been an expression with negative associations, being synonymous with kitch and banal. Over the last 10 years, Turkish cinematography has become recognised as the “New cinema of Turkey” thanks to appearances in festivals in Rotterdam, Linz, New York and Wrocław, Poland (“Era New Horizons”, 2010). -

WINTER SLEEP (Kiş Uykusu)

WINTER SLEEP (Kiş Uykusu) A film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan FIPRESCI Prize Cannes 2014 196 min - 1:2.40 - 5.1 - Turkey / Germany / France Opens November 21, 2014 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E-mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films [email protected] 10 Margaret Street London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095 newwavefilms.co.uk Synopsis The film is set in the hilly landscape of Cappadocia in Central Anatolia, where the local celebrity, a former actor Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), owns a small hotel cut into the hillside. It’s now winter and the off-season. Aydin runs the hotel with his younger wife Nihal (Melisa Sözen), writes a column for the local newspaper, and is playing with the idea of producing a book on Turkish theatre. He has also inherited local properties from his father, but leaves the business of rent collection to his agent. When a local boy, resentful of his father’s humiliation at the hands of the agent, throws a stone at a jeep whilst Aydin and his agent are driving in it, Aydin ducks out of any responsibility or involvement. As the film progresses, the cocoon in which the self-satisfied and insular man has wrapped himself is gradually unravelled . In a series of magnificent set pieces, the film takes a close look at Aydin's interactions with his wife, his recently divorced sister, and the family of the stone-throwing boy. Aydin is finally brought face-to-face with who and what he truly is. -

TUR 329: TURKISH CINEMA Spring 2019

University of Texas at Austin Department of Middle Eastern Studies TUR 329: TURKISH CINEMA Spring 2019 Unique #: 41385 Course Hours and Room: Instructor: Jeannette Okur MWF 12:00-1:00 PM in PAR 103 Office: CAL 509 Office Hours: T-TH 11:00 AM-12:00 PM Email: jeannette.okur @austin.utexas.edu or by appointment Course Description: Global flows of information, technology, and people have defined Turkish cinema since its inception in the early 20th century. This course, taught entirely in Turkish, will introduce different approaches to studying cinema, while also providing students with the opportunity to achieve advanced-level language skills. This is a screening-intensive course, and we will watch a wide range of films, including popular, arthouse, auteur-made, generic, and independent works. In each unit, we will read film history and criticism in both Turkish and English and closely examine primary sources in their original language. Our goal will be to determine what constitutes Turkish cinema as a national cinema and identify the ways in which its constitutive elements are part of transnational movements. To this end, we will discuss the socio-political contexts, industrial trends, aesthetic sensitivities, and representation strategies of selected films. By constantly reformulating the essential question of “what Turkish cinema is,” we seek to understand how Turkey’s filmmakers, critics, cultural policy-makers, and viewers have answered this question in different historical periods. Prerequisite: TUR 320K/TUR381K with a letter grade of C or higher (or via placement via successful performance on the DMES Turkish placement exam) Language/Content Learning Objectives: By the end of TUR 329 you will, inşallah: • initiate, sustain, and close a general conversation with a number of strategies appropriate to a range of circumstances and topics, despite errors. -

Silencing on Board Silent Representations of Women in the New Turkish Cinema

Silencing On Board Silent Representations of Women in the New Turkish Cinema By Ozlem Guclu Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies Supervisor: Professor Jasmina Lukic Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2007 Abstract: This study explores the functions of the different forms of silences of the female characters on the New Turkish Cinema screen through representative examples. I discuss the functions of the silences of female stories, female point of view and female characters under the four main types of silences- silencing silences, resisting silences, complete silences and speaking silences in order to reveal both the dominant meanings and the possibilities and limits of the alternative meanings. CEU eTD Collection I Acknowledgements: I want to thank my supervisor Jasmina Lukic for her tremendous support, and for everything she taught me. She is the one who always trusted in my work and motivated me every time I lost my patience and energy. I want to thank all of my dear friends for making life bearable, easier and fun during the thesis writing period. CEU eTD Collection II Table of Contents: Introduction:.........................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: The New Turkish Cinema and Women's Silences............................................4 1.1 The New Turkish Cinema: .........................................................................................4