Enlistment, Conscription, Exemption, Tribunals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 1

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE EAST LINDSEY LOCAL PLAN ALTERATION 1999 The Local Plan has the following main aims:- x to translate the broad policies of the Structure Plan into specific planning policies and proposals relevant to the East Lindsey District. It will show these on a Proposals Map with inset maps as necessary x to make policies against which all planning applications will be judged; x to direct and control the development and use of land; (to control development so that it is in the best interests of the public and the environment and also to highlight and promote the type of development which would benefit the District from a social, economic or environmental point of view. In particular, the Plan aims to emphasise the economic growth potential of the District); and x to bring local planning issues to the public's attention. East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Page The Aims of the Plan 3 How The Policies Have Been Formed 4 The Format of the Plan 5 The Monitoring, Review and Implementation of the Plan 5 East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 2 INTRODUCTION TO THE EAST LINDSEY LOCAL PLAN 1.1. The East Lindsey Local Plan is the first statutory Local Plan to cover the whole of the District. It has updated, and takes over from all previous formal and informal Local Plans, Village Plans and Village Development Guidelines. It complements the Lincolnshire County Structure Plan but differs from it in quite a significant way. The Structure Plan deals with broad strategic issues and its generally-worded policies do not relate to particular sites. -

The London Gazetted 17 June, 1955 3533

THE LONDON GAZETTED 17 JUNE, 1955 3533 URBAN DISTRICT OF NANTWICH. shall 'be according to the number of thermsi supplied and the Wales Gas Board hereby declare that as. CONFIRMATION OF BYELAWS. and from the said date the Calorific Value of the NOTICE is hereby given that the Urban District Gas to be supplied from the said Works shall be Council of Nantwich, intend, after the expiry of one 47'5 British Thermal Units per cubic foot. calendar month from the date of the publication of 2. This declaration shall take effect for the purpose this notice to apply to the Minister of Housing and of calculating the charge to be made for the Gas Local Government for confirmation of Byelaws made supplied to any consumers! immediately after the by the Council under section 108 of the Public first reading of that consumer's meter after the Health Act, 1936, with respect to the trades of fell- 1st October, 1955. monger or tanner in the Urban District of Nantwich. Dated this 14th day of June, 1955. D. TUDOR EVANS, Clerk of the Council. C. B. MAWER, Secretary, Wales Gas Board. Council Offices, 2, Windsor Place, " Brookfield House," Nantwich, Cheshire. Cardiff. (357) 14th June, 1955. (082) TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT, 1947. TENDRING RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL. COUNTY OF LINCOLN—PARTS OF LINDSEY. COAST PROTECTION ACT, 1949. The County of Lincoln, Parts of Lindsey THE Council of the Rural District of Tendring Development Plan. acting in their capacity as coast protection authority NOTICE is hereby given that on the 26th day of hereby give notice under paragraph 1 of the Second May, 1955, the Minister of Housing and Local Schedule to the above Act that they intend to make Government approved with modifications the above an Order applying the provisions of Section 18 of Development Plan. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Huttoft Boat Shed Visitor Centre.Pdf

Executive Councillor Open Report on behalf of Andy Gutherson, Executive Director – Place Councillor E J Poll, Executive Councillor: Commercial Report to: and Environmental Management Date: 25 October 2019 Subject: Huttoft Boat Shed Visitor Centre Decision Reference: I018558 Key decision? No Summary: This project will add another quality tourist facility to the Lincolnshire Coast, building on the success of the North Sea Observatory and the Gibraltar Point Visitor Centre. Funded by the County Council and the GLLEP the building at Huttoft will replace an existing redundant boat shed, owned by the County Council. The new building will contain a high quality cafe, a rooftop viewing deck (protected by a glass balustrade) and an external ground level deck for hosting larger pop-up food and other events. The building will benefit from floor to ceiling windows (protected when not in use by shutters) giving views inland to the Wolds and North to Sandilands and Sutton On Sea. The project will include the refurbishment of the existing public toilets, an external shower for beach users and connecting the site to main services for the first time. The site will be let, at a commercial rent, to a new commercial operator, who will be responsible for maintaining the building and the toilets. The planning application has been submitted. Subject to receiving planning permission works should start on site early in 2020 and the building open to the public in June 2020. Recommendation(s): That the Executive Councillor :- 1) Approves the delivery of the Huttoft Boat Shed Cafe Visitor Centre Project. 2) Approves in principle the procurement and award of a contract for the 1 Project subject to prior formal documented termination of the occupational arrangements granted to East Lindsey District Council for the existing public conveniences. -

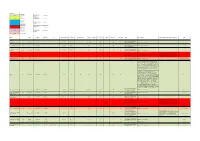

OK to EDIT Section 106 Agreement Master List

Colour Key : Completed/ no Total in S106 Funds Green further action £12,106,547.78 negotiated. required Total S106 Funds Ongoing, monies Yellow received in by the £1,714,805.54 in but not spent Council. Ongoing trigger needs to be Total S106 Funds Spent Blue monitored or £783,995.60 by ELDC checked, money needs to be got in Needs an action Total S106 Funds Red which is not £930,809.94 Unspent normal monitoring Annual payment Not Yet Received inc Purple being made to money for LCC £10,391,742.24 neighbourhoods Education Orange Application expired Section 106 Total Monies Total Monies Monies received not Deadline for Monies not yet Location Parish Planning Ref Notes Total monies negotiated Date monies received Date spent Spend agreed Trigger Terms of Agreement Comments relating to spend / transfer/notes on progress Status agreement date received spent spent spend received 1991 Upon the completion of the transfer of the Banovallum Gardens Horncastle Green Horncastle S/086/182/91 £15,665.00 £15,665.00 £15,665.00 £0.00 £0.00 Yes Public Open Space the owners will pay the Maintenance of Public Open Space Completed council the sum of £15,665.00 1992 Upon the completion of the transfer of the Land off Station Road, Sibsey Green Sibsey S/152/0029/92 £15,000.00 £15,000.00 £15,000.00 £0.00 £0.00 Yes Public Open Space the owners will pay the Maintenance of Public Open Space Completed council the sum of £15,000.00 1993 Upon the completion of the transfer of the Land at Bowl Alley Lane Farm, Green Horncastle S/086/1801/90 £3,910.39 £3,910.39 £3,910.39 £0.00 £0.00 Yes Public Open Space the owners will pay the Maintenance of Public Open Space Completed Horncastle town council the sum of £3,910.39 16/10/19 - Land has never been transferred, found out when the 6 months after commencement the land parish meeting are trying to sort out a potential encroachment on Transfer of land to Haltham Parish meeting to be used as public open Land at Haltham called The Green Red Haltham S/07/615/92 16.2.93 £0.00 should be transferred to the Haltham Parish the land. -

Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Farm Limited Triton Knoll Electrical System All Pre-Existing Rights Reserved

Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Farm Limited TRITON KNOLL ELECTRICAL SYSTEM Environmental Statement Volume 3 Chapter 9: Traffic and Access April 2015, Revision A Document Reference: 6.2.3.9 Pursuant to: APFP Reg. 5(2)(a) Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Farm Ltd Triton Knoll Electrical System Environmental Statement - Volume 3 Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Farm Limited Copyright © 2015 Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Farm Limited Triton Knoll Electrical System All pre-existing rights reserved. Environmental Statement Liability In preparation of this document Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Volume 3: Chapter 9 – Traffic and Access Farm Limited (TKOWFL), a joint venture between RWE Innogy UK (RWE) and Statkraft UK, and subconsultants working on behalf of TKOWFL have made reasonable efforts April 2015 to ensure that the content is accurate, up to date and complete for the purpose for which it was prepared. Neither TKOWFL nor their subcontractors make any warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of material supplied. Other than Drafted By: Ian Wickett, RSK any liability on TKOWFL or their subcontractors detailed in the contracts between the parties for this work neither TKOWFL Approved By: Kim Gauld-Clark or their subcontractors shall have any liability for any loss, damage, injury, claim, expense, cost or other consequence Date of Approval April 2015 arising as a result of use or reliance upon any information contained in or omitted from this document. Revision A Any persons intending to use this document should satisfy themselves as to its applicability for their intended purpose. Where appropriate, the user of this document has the Triton Knoll Offshore Wind Farm Ltd obligation to employ safe working practices for any activities referred to and to adopt specific practices appropriate to local Auckland House conditions. -

Draft Recommendations for East Lindsey District Council on Our Interactive Maps At

Contents Summary 1 1 Introduction 3 2 Analysis and draft recommendations 5 Submissions received 6 Electorate figures 6 Council size 6 Electoral fairness 7 General analysis 7 Electoral arrangements 8 Rural East Lindsey 8 Louth 12 Mablethorpe 14 Skegness 15 Conclusions 16 Parish electoral arrangements 17 3 What happens next? 19 4 Mapping 21 Appendices A Table A1: Draft recommendations for East Lindsey 22 District Council B Glossary and abbreviations 25 Summary The Local Government Boundary Commission for England is an independent body that conducts electoral reviews of local authority areas. The broad purpose of an electoral review is to decide on the appropriate electoral arrangements – the number of councillors, and the names, number and boundaries of wards or divisions – for a specific local authority. We are conducting an electoral review of East Lindsey District Council to provide improved levels of electoral equality across the authority. The review aims to ensure that the number of voters represented by each councillor is approximately the same. The Commission commenced the review in December 2011. This review is being conducted as follows: Stage starts Description 3 September 2012 Consultation on council size 27 November 2012 Submission of proposals for warding arrangements to LGBCE 19 February 2013 LGBCE’s analysis and formulation of draft recommendations 14 May 2013 Publication of draft recommendations and consultation on them 6 August 2013 Analysis of submissions received and formulation of final recommendations Submissions received We received 12 submissions during our consultation on council size and nine submissions during consultation on warding arrangements. All submissions can be viewed on our website at www.lgbce.org.uk Analysis and draft recommendations Electorate figures As part of this review, East Lindsey District Council submitted electorate forecasts for the year 2018, projecting an increase in the electorate of approximately 5% over the six-year period from 2012–18. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25Ra APRIL 1969 4407

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25ra APRIL 1969 4407 LINCOLN—PARTS OF LINDSEY COUNTY is to prohibit the waiting of vehicles on the east side COUNCIL of North Street, Gainsborough, and to restrict the The County Council of Lincoln—Parts of Lindsey waiting of vehicles on the west side of North Street, (Spilsby) (Traffic Regulation) Order, 1969 Gainsborough. A copy of the Order and a map showing the road Notice is hereby given 'that the County Council of to which the Order relates may be inspected at Lincoln, Parts of Lindsey propose to make an Order County Offices, Newland, Lincoln, during normal under section 1 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act office hours. 1967, as amended by Part IX of the Transport Act 1968, which will impose waiting restrictions in Post W. E. Lane, Clerk of the County Council. Office Lane, Reynard Street, Market Street, Halton County Offices, Road, Queen Street and Ashby Road, Spilsby. Lincoln. A copy of the proposed Order and a map showing 25th April 1969. (3H) the roads to which the proposed Order relates, to- gether with a statement of the reasons for proposing to make the Order, may be inspected free of charge at County Offices, Newland, Lincoln, and the offices LINCOLN—PARTS OF LINDSEY COUNTY of the Spilsby Rural District Council, Council Offices, COUNCIL Toynton Hall, Spilsby, during normal office hours. The County Council of Lincoln—Parts of Lindsey Objections to the proposals, together with the (Immingham) (Traffic Regulation) Order 1969 grounds on which they are made, must be sent in Notice is hereby given that on the 18th April 1969 writing to the undersigned by 17th May 1969. -

Authority Monitoring Report 2018-19

EAST LINDSEY DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL PLAN MONITORING FRAMEWORK AUTHORITY MONITORING REPORT 1st March 2018 to 28th February 2019 Supporting Economic Growth for the Future 1 .............................................................................................................. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 4 2.0 THE EAST LINDSEY DEVELOPMENT PLAN ....................................... 6 2.8 Neighbourhood Plans ................................................................................. 6 2.11 Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) ..................................................... 7 2.12 Duty to Co-operate ................................................................................. 7 2.14 Shared Information ................................................................................ 7 3.0 DATA COLLECTION AND REVIEW ................................................... 8 4.0 OVERSIGHT AND SCRUTINY .......................................................... 9 5.0 EAST LINDSEY ECONOMIC ACTION PLAN ...................................... 9 6.0 HOUSING GROWTH AND LAND SUPPLY ANNUAL POSITION STATEMENT. ........................................................................................ 10 6.14 Second Hand Housing Market ............................................................... 13 6.17 Affordable Housing ............................................................................... 13 6.26 Brownfield Land Register ..................................................................... -

Lincol~Shire

7 554 RPILSBY. .LINCOL~SHIRE. [KELLY 8 ing 30 acres of glebe, with residPnce, in the gift of the · The charities amount to [r34 6s. yearly, for the·benefit of Earl of Ancaster, and held since 1910 by the Rev. BPr- the poor, and consist of the fo.lowing yearly rent-charges: nard-Steinmetz M.A. of New College, Oxford, who is also /1 ss. left by Tobias Anderson, a former vicar; ss. by Wm. vicar {)f Hundlrby. The churchyard was closed, except Wayet; 4s. by John Wayet, in 1705, and zos. for apprentice for interments in vaults and brick graves, by an Order in fees; 10s. by John Hutton in 1759, and zos. left by Henry Council, dated 13th September, 1884. 'fhe parish rooms, Mowbray, in 1697, for apprentice fees. The poor's land has New Spilsby, formerly a Primitive Methodist chapel, been vested in trust for the benefit of the po<Jr from time were purchased in r89r. The Catholic church, in immemorial; it comprises about 22 a.cres, including an Church ·street., a structure in the Gothic style, is allotment of r3a. I7P· awarded to it at the inclosure of the dedicated to Our Lady and the English Martyrs, and East Fen; upon the old poor's land are several tenements was opened in 1902 by the Right Rev. Dr. Brindle and the Red Lion public-house; the whole lets for about D.S.O. and affords sittings for about. 140 persons. The £rog which is distributed in half-yearly moieties. Wesleyan chapel was erected in 1878, at a cost of £7,ooo, Sir John .Franklin Id. -

The London Gazette, 13Th February. 1970 1883

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13TH FEBRUARY. 1970 1883 A copy of the proposed Order and the map A copy of the proposed Order together with a showing the road to which the proposed Order map showing the land to which the Order relates relates together with a statement of reasons may be may be seen at the Town Hall, Widmore Road, inspected ait County Offices, Newland, Lincoln, and Bromley, on Monday to Friday between the hours the offices of the Spilsby Rural District Council, of 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. Council Offices, Toynton Hall, Spilsby, during If anyone wishes to object to the Order, the normal office hours. objection, with the grounds for making it, should Objections to the proposals, together with the be -made in writing to the undersigned not later grounds on which they are made, must be sent in than -the 6th March 1970. writing to .the undersigned by 9flh March 1970. T. W. Fagg, Town Clerk. W. E. Lane, Clerk of the County Council. Town Hall, County Offices, Bromley. (430) Lincoln. Dated 13th February 1970. (322) LONGBENTON URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL The Urban District of Longbenton (Benton Lane LINCOLN COUNTY COUNCIL- and Great Lime Road) (Prohibition of Driving) PARTS OF LINDSEY Order 1970. The County Council of Lincoln—Parts of Lindsey Notice is hereby given that the Urban District (Frithville) (Weight Restriction) Order 1970 Council of Longbenton have made an Order under Notice is hereby given that the County Council of section 1 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1967, Lincoln, Parts of Lindsey propose to make an Order as amended by Part IX of the Transport Act 1968, under section 1 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act which will come into force on the 23rd February 1967, as amended by Part IX of the Transport Act 1970. -

East Lindsey Coastal Zone Skills Audit

EAST LINDSEY COASTAL ZONE SKILLS AUDIT FINAL REPORT Terence Hogarth, David Owen, Anne Green, Mark Samuel, Maria de Hoyos and Lynn Gambin Institute for Employment Research (in collaboration with IFF Research) University of Warwick Coventry UK-CV4 7AL Tel: +44 24 76 52 44 20 Fax: +44 24 76 52 42 41 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] June 2010 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. x 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Aims of the Study ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Method ................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 East Lindsey and the Coastal Zone .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Structure of the Report ........................................................................................................... 3 2. Skills Investments – the Special Case of Rural, Peripheral and Coastal Areas ................................ 4 2.1 Stimulating Skill Demand ........................................................................................................ 4 2.2 The Low Skill Equilibrium? .....................................................................................................