Eastern Wind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concert De Printemps

ASSOCIATION DES ANCIENS #MUSIQUE_DE_CHAMBRE ÉLÈVES ET DES ÉLÈVES DU #RÉCITAL CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS CONCERT DE PRINTEMPS JEUDI 21 MARS 2019 19 H SALLE D'ORGUE CONSERVATOIRE DÉPARTEMENT NATIONAL SUPÉRIEUR DES DISCIPLINES DE MUSIQUE ET INSTRUMENTALES DE DANSE DE PAR I S CLASSIQUES SAISON 2018-2019 ET CONTEMPORAINES CONCERT DE PRINTEMPS CONSERVATOIRE DE PARIS SALLE D'ORGUE JEUDI 21 MARS 2019 19 H L'association des élèves et anciens élèves des Conservatoires nationaux supérieurs de musique, de danse et d'art dramatique a été créée en 1915 par son président fondateur, le compositeur Alfred Bruneau. Elle a été reconnue d'utilité publique dès 1918. Elle est donc sinon la plus ancienne, du moins l'une des plus anciennes associations culturelles de France. Son rôle est essentiellement un rôle de solidarité entre les générations d'artistes formés par ces établissements. Elle organise tous les ans pas moins d'une centaine de concerts dont ce concert de printemps au Conservatoire. L'Association des anciens élèves et élèves du CNSMDP bénéficie du soutien de la Banque de France CONCERT DE PRINTEMPS 3 PROGRAMME JOHANNES BRAHMS Sonate n° 1 en mi mineur op. 38 I. Allegro molto II. Allegretto quasi menuetto III. Allegro Stéphanie Huang, violoncelle LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Didier Nguyen, piano An die ferne Geliebte, op. 98 Thomas Ricart, tenor MARIO CASTELNUOVO-TEDESCO Katia Weimann, piano Prélude et Fugue IX MAREK PASIECZNY ALFRED DESENCLOS Lutoslawski : In memorium Quatuor de saxophones I. Allegro non troppo MAURICE OHANA II. Andante Anonyme du XXe siècle -

Agenda Des Concerts Et Évènements Maurice Ravel

1 AGENDA DES CONCERTS ET ÉVÈNEMENTS MAURICE RAVEL DE LA SAISON 2013-2014 A PARIS (SAUF EXCEPTION) (liste non exhaustive) par Manuel CORNEJO pour les Amis de Maurice RAVEL (Mise en ligne : 16 juillet 2013 ; Dernière actualisation : 23 juin 2014) ● Mardi 1er octobre 2013 12h30 Salle Cortot (« Les Concerts de Midi & Demi ») étudiants de niveaux supérieurs et professeurs de l’École Normale de Musique BEETHOVEN : 6 Bagatelles op. 126 PROKOFIEV : Sonate n°6 op. 82 BOLCOM : New Etudes n°12 « Hymne à l’Amour » Maurice RAVEL : La Valse http://sallecortot.com/fiche.cfm/36901/les_concerts_de_midi_&_demi.html ● Mercredi 2 octobre 2013 20h Salle Pleyel Orchestre de Paris, direction : Paavo Järvi, piano : Piotr Anderszewski Claude DEBUSSY : Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune Béla BARTÓK : Concerto pour piano n°3 Igor STRAVINSKI : Symphonie en trois mouvements Maurice RAVEL : Boléro http://www.sallepleyel.fr/francais/concert/13266-orchestre-de-paris-paavo-jarvi-piotr-anderszewski ● Samedi 5 et dimanche 6 octobre 2013 78490 Montfort-l’Amaury Festival Journées Ravel (18e édition) http://www.lesjourneesravel.com/IMG/pdf/programmeravel2013v7.pdf Samedi 5 octobre 2013 15h, 16h et 17h Concerts « Prom’S » : 3 sur 4 Promenade musicale, invitation au voyage au cœur historique de Montfort l’Amaury. Telle est la formule : Choisissez 3 programmes parmi les 4 proposés et faites ainsi vos Prom’S à la carte, suivant ainsi votre itinéraire musical personnel : 1. L’Atelier, 5 bis, rue de Versailles Clément Lefèbvre, piano W. A. MOZART : Rondo kv 511 J-P. RAMEAU : Les trois mains Francis POULENC : 3e novelette Maurice RAVEL : A la manière de Borodine et Chabrier Emmanuel CHABRIER : Bourrée fantasque 2. -

Ideazione E Coordinamento Della Programmazione a Cura Di Massimo Di Pinto Con La Collaborazione Di Leonardo Gragnoli

Ideazione e coordinamento della programmazione a cura di Massimo Di Pinto con la collaborazione di Leonardo Gragnoli gli orari indicati possono variare nell'ambito di 4 minuti per eccesso o difetto Sabato 6 febbraio 2016 00:00 - 02:00 euroclassic notturno verhulst, johannes (1816-1891) ouverture in do min op. 3 "gijsbrecht van aemstel" netherlands radio symphony orch dir. jac van steen durata: 8.52 NOS ente olandese per le trasmissioni enescu, george (1881-1955) pezzo da concerto per vla e pf tabea zimmermann, vla; monique savary, pf durata: 8.56 RSR radio della svizzera francese marcello, alessandro (1669-1747) concerto in re min allegro - adagio - presto. jonathan freeman-attwood, trba; colm carey, org durata: 8.50 BBC british broadcasting corporation bach, johann sebastian (1685-1750) o jesu christ, mein's lebens licht, cantata BWV 118 concerto vocale ghent dir. philippe herreweghe (reg. breslavia, 05/02/2014) durata: 8.43 PR radio polacca brahms, johannes (1833-1897) rapsodia per pf in sol min op. 79 n. 2 robert silverman, pf durata: 6.53 CBC canadian broadcasting corporation schmitt, matthias (1958) ghanaia, per percus colin currie, marimba (reg. 19/11/2003) durata: 6.54 BBC british broadcasting corporation boeck, august de (1865-1937) fantasia per orch su due canzoni popolari fiamminghe flemish radio orch dir. marc soustrot (reg. at brussels, 25-28/06/2007) durata: 7.00 VRT radiotelevisione belga (fiamminga) mozart, wolfgang amadeus (1756-1791) serenata in do min per ottetto di fiati K388 (K384a) allegro - andante - menuetto in canone - trio al rovescio - allegro. bratislava chamber harmony dir. justus pavlik durata: 22.14 SR radio slovacca norman, ludvig (1831-1885) quartetto per archi in mi mag op. -

Si Pour Un Homme Avoir Vingt Ans C'est

1 i pour un homme avoir vingt ans c’est erveilleuse aventure que celle de nos être encore au seuil de l’enfance, pour "Journées Ravel" qui fêtent cette S un festival c’est déjà l’âge mûr et le M année leur vingtième anniversaire. temps de l’accomplissement. C’est aussi le mo- Si la renommée mondiale de Maurice Ravel conférait ment de mesurer le chemin parcouru, d’évaluer une légitimité évidente à la création d’un festival de les tâches qui restent à accomplir et surtout de musique à Montfort l’Amaury, il aura fallu l’enthou- remercier tous ceux qui ont permis, au long de ces siasme et la détermination d’Annick de Beistegui, vingt années, la réalisation concrète de cette idée entourée de quelques fidèles soutiens, pour que les simple : servir sur les lieux-mêmes de sa vie la "Journées Ravel" voient le jour et acquièrent la noto- musique et la mémoire de Maurice Ravel. riété qui est la leur aujourd’hui. Ils sont nombreux ceux qui, autour du petit cercle Ce rendez vous automnal attendu nous réunit désor- initial de l’Association des Journées Ravel, ont dé- mais depuis vingt ans avec l’ambition de créer un mo- cidé en 1996 de franchir le pas et de se lancer dans ment d’exception et de bonheur partagé autour de la l’aventure de créer à Montfort l’Amaury un festival Musique, du Beau et de l’Excellence… de musique : la Municipalité de la ville, le Conseil Depuis ses débuts, sous la direction artistique d’Eglée Général des Yvelines, les entreprises partenaires, de Crignis puis celle de Rémi Lerner, notre festival a le bénévolat local, les artistes bien sûr, et surtout accueilli à Montfort l’Amaury les meilleurs interprètes. -

Cello Biënnale 2010 M.M.V

welkom 2 welcome 3 programma-overzicht 4 programme overview 4 programma’s 9 programmes 9 musici 103 musicians 103 informatie 139 information 139 amsterdamse cellobiënnale amsterdamse cellobiënnale Beste Biënnale-bezoeker, Dear Biennale visitor, Zelfs de grootste liefhebbers van de Amsterdamse Cello Biënnale hebben hun hart Even the Amsterdam Cello Biennale’s most fanatical devotees endured doubts as vast gehouden of het in deze financieel moeilijke tijden nog wel mogelijk zou zijn to whether a festival of such dimensions could still be realised in these troubled een festival van die omvang te realiseren. Maar de Biënnale 2010 is er. En hoe! financial times. However, the 2010 Biennale has indeed arrived – and how! With Met de muziek voor cello-ensembles als rode draad door de programmering is de music for cello ensembles as the main theme of the programming, the 2010 Biennale Biënnale 2010 nog omvangrijker en internationaler dan de vorige edities. De spelers is even more extensive and internationally oriented than the previous editions. The komen uit Berlijn, New York en Parijs, maar ook uit Peking en Riga. Daarom willen players come from afar: Berlin, New York and Paris, even Beijing and Riga. So first we allereerst onze grote dank en waardering uitspreken voor de sponsors, culturele of all we would like to express our deepest gratitude and appreciation towards the fondsen, begunstigers en vrienden die het opnieuw mogelijk hebben gemaakt onze sponsors, cultural funds, patrons and friends who have once again enabled us to (en wellicht ook uw) droombiënnale te realiseren. realise our (and maybe also your) dream Biennale. Dit Festivalboek biedt u een overzicht van alle concerten en evenementen met This Festival booklet provides an overview of all concerts and events with descriptive samenvattende beschrijvingen. -

Cello Biënnale 2008 M.M.V

20 20 20 20 20082008 082008 programma Hoe klinktHoe klinkt het geluid geluid van eenvan een cellokist? cellokist? Mascha van Nieuwkerk, Zeist 1990, celliste. Met alleen een lege cellokist begint ze niet veel. Maar een cello kost heel veel geld – zoveel dat veel musici zich de aanschaf niet kunnen veroorloven. Het Nationaal Muziekinstrumenten Fonds (NMF) helpt hen. Mascha bijvoorbeeld heeft eerder een cello van Jacobus Stainer (Absam 1600 - 1650) in bruikleen gekregen en speelt tegenwoordig op een cello van het NMF (Jaap Bolink, Hilversum 1984). Zodat u daarvan kunt genieten. TALENT ZOEKT INSTRUMENT | FONDS ZOEKT DONATEURS | NMF | Sint Annenstraat 12, 1012 HE Amsterdam | 020 6221255 | [email protected] | | www.muziekinstrumentenfonds.nl | ABN AMRO 55 50 28 666 | NMF_Mascha_cellobien_2008.indd 1 24-09-2008 16:47:21 welkom 004 programma-overzicht 006 programma’s & toelichtingen 014 deelnemers nationaal celloconcours 103 biografieën 108 informatie 130 inhoud Welcome to all visitors of the Amsterdam Cello Biennale! The musical success of the first Amsterdam Cello Biennale and, equally, the festive feeling of solidarity uniting visitors and performers alike have been a continual source of inspiration in conceiving and realising the new Festival programme. Besides countless new faces, new music and new formulas, we have consciously retained those elements that proved to be so enriching last time that they are worthy of repetition. For, just as in music itself, the repetition of certain themes can have an even stronger impact through subtle variations or fine embellishments. The second time around, one is struck by details that previously escaped notice. And behold, suddenly an entirely new melody or unexpected rhythmic element is created. -

Du 22 Août Au 1Er Septembre 2019 Giverny, Vernon, Notre Dame De L’Isle, Saint Pierre D’Autils Normandie

du 22 août au 1er septembre 2019 Giverny, Vernon, Notre Dame de l’Isle, Saint Pierre d’Autils Normandie 16ème édition : “L’Europe dans tous ses états” Direction Artistique : Michel STRAUSS 13 concerts exceptionnels – 33 musiciens Compositeurs invités : Peter EÖTVÖS, Martial SOLAL et Vladimir COSMA Œuvres de BARTÓK, BEETHOVEN, BRAHMS, CHAUSSON, SCHUMANN, COSMA, CRAS, DOHNANYI, DUPARC, DVOŘÁK, ELGAR, ENESCO, ETÖVÖS, FAURE, FRANCK, GERSHWIN, HONNEGER, JÁNAČEK, LUTOSLAWSKI, MAHLER, MASSENET, MENDELSSOHN, MOZART, POULENC, RAVEL, SCHREKER, SCHUBERT, SMETANA, SOLAL, STRAUSS, SUK, ZEMLINSKY DOSSIER DE PRESSE Contact presse : Nathalie Tiberghien [email protected] - 06 03 21 48 98 1/30 Les partenaires en 2019 la force des artistes 2/30 Partenaire principal du festival Ker-Xavier Roussel. Jardin privé, jardin rêvé 27 juillet – 11 novembre 2019 L’exposition Ker-Xavier Roussel. Jardin privé, jardin rêvé propose de découvrir une centaine d’œuvres du peintre Ker-Xavier Roussel (1867-1944), depuis ses expérimentations nabies des années 1890 jusqu’aux vastes narrations mythologiques qu’il revisite avec une force constante au tournant du XXe siècle. L’exposition montre la puissance décorative de l’artiste ainsi que des estampes évoquant la mélancolie crépusculaire du symbolisme fin-de-siècle. C’est également l’occasion de reconstituer certains décors dispersés dont le format et la palette ne manqueront pas de surprendre. Exposition organisée par le musée des impressionnismes Giverny avec le soutien exceptionnel du musée d’Orsay. Le Pêcheur, -

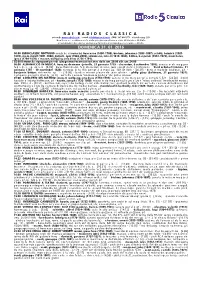

R a I R a D I O 5 C L a S S I C a Domenica 31. 01. 2016

RAI RADIO5 CLASSICA sito web: www.radio5.rai.it e-mail: [email protected] SMS: 347 0142371 televideo pag. 539 Ideazione e coordinamento della programmazione a cura di Massimo Di Pinto gli orari indicati possono variare nell'ambito di 4 minuti per eccesso o difetto DOMENICA 31. 01. 2016 00:00 EUROCLASSIC NOTTURNO: musiche di veracini, francesco (1690-1768), brahms, johannes (1833-1897), schütz, heinrich (1585- 1672), matz, rudolf (1901-1988), kuljeric, igor (1938-2006), schumann, robert (1810-1856), britten, benjamin (1913-1976), moscheles, ignaz (1794-1870) e mozart, wolfgang amadeus (1756-1791). 02:00 Il ritornello: riproposti per voi i programmi trasmessi ieri sera dalle ore 20:00 alle ore 24:00 06:00 ALMANACCO IN MUSICA: françois devienne (joinville, 31 gennaio 1759 - charenton, 6 settembre 1803): sonata in do mag per fag e b. c. op. 24 n. 6 - [8.10] - klaus thunemann, fag; klaus stoll, violone; jörg ewald dahler, fortepiano - franz schubert (vienna, 31 gennaio 1797 - 19 novembre 1828): fantasia in fa min per pf a 4 mani op. 103 (D 940) - [20.29] - katia e marielle labeque, pf - benjamin britten: sinfonietta op. 1 - [15.06] - london mozart player dir. jane glover - philip glass (baltimora, 31 gennaio 1937): company, per orch d'archi - [8.14] - orch da camera "kremerata baltica" dir. gidon kremer 07:00 CONCERTO DEL MATTINO: mozart, wolfgang amadeus (1756-1791): sonata in do mag per pf a 4 mani K 521 - [24.50] - ingrid haebler e ludwig hoffmann, pf - haydn, joseph (1732-1809): messa in do mag per soli coro e orch "missa cellensis" (mariazeller messe) Hob. -

Maja Bogdanovic Cellist

Maja Bogdanovic Cellist Following her stunning recital debut at Carnegie’s Weill Hall, The Strad hailed cellist Maja Bogdanovic for “an outstanding performance of exceptional tonal beauty and great maturity of interpretation.” Since then, she has taken her place among today’s foremost cellists. In the U.S., Ms. Bogdanovic made her debut at the 2017 Grand Teton Music Festival, playing Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 under the baton of guest conductor Cristian Macelaru. She has also performed with the Spokane Symphony (Elgar Concerto) and twice with the Lubbock Symphony (Shostakovich Concerto No. 1 and Dvorák Concerto). This season, she brought the Dvorák Concerto to California for her debut with the Bakersfield Symphony. In 2018/2019, she returns to the Americas to make debuts with the Ft. Worth Symphony, performing the Saint-Saëns Concerto No. 1, as well as with the Minas Gerais Philharmonic in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, performing Friedrich Gulda’s Cello Concerto. While in Texas, she will also appear with the Lubbock Symphony, playing the Schumann Concerto. Worldwide concerto engagements include the Belgrade Philharmonic, Berlin Symphony, Bergische Philharmonie, Bremerhaven Staatsorchester, Korean Wonju Philharmonic Orchestra, Morelia Philharmonic/Mexico, Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire, Salta Symphony/Argentina, Serbian Radio Orchestra, Slovenian Philharmonic, St. Bartholomew Orchestra/London, Sydenham Festival Orchestra, Tokyo Philharmonic, the Tonhalle Orchester/Zurich, as well as chamber orchestras which include Nouvelle Europe, Dušan Skovran, St. George Strings, Sejong Soloists, and the Munich Chamber Orchestra. An avid chamber musician, Maja Bogdanovic performs regularly at the Kuhmo Festival in Finland, and has performed recently at the Stift International Chamber Music Festival in The Netherlands. -

21-28 Juillet 2010

1er FESTIVAL DE MUSIQUE DE CHAMBRE D’OBERNAI 21-28 Juillet 2010 1 er FESTIVAL DE M USIQUE DE CHAMBRE D’OBERNAI 21-28 Juillet 2010 REVUE DE PRESSE REVUE DE PRESSE 2010 1 www.festivalmusiqueobernai.com 1er FESTIVAL DE MUSIQUE DE CHAMBRE D’OBERNAI 21-28 Juillet 2010 Dernières Nouvelles d'Alsace Vendredi 30 juillet 2010 « Feux d'artifice romantiques » Geneviève Laurenceau (à gauche), a excellé dans son rôle de prima donna pendant une semaine musicale à succès. (Photo DNA) Le Festival vient d'achever mercredi un premier parcours sans faute. C'est promis, ce ne sera pas le dernier. Geneviève Laurenceau, âme de cette riche semaine musicale et culturelle, s'est à bon droit félicitée d'une évidente réussite marquée par une fréquentation sans fléchissement. Obernai représente avec elle, par la voix de son maire, l'engagement d'une équipe et l'accueil d'un public conquis. La flamme du sextuor formé pour le concert de clôture a ainsi mis le comble à l'enthousiasme. Bien remplie par les deux oeuvres inscrites au programme, cette soirée s'ouvrait par le rarissime Quintette à cordes en la mineur posthume de Max Bruch. L'oeuvre est la musique de chambre de Bruch étant restée longtemps limitée aux belle Pièces pour clarinette, alto et piano de 1908. Ce quintette-ci date de 1918. On y retrouve le charme mélodique que déployait le compositeur dans les deux quatuors de sa pétulante jeunesse. Mais, alors que ces derniers étaient imprégnés de l'influence de Mendelssohn, c'est le patronage de Brahms qui transparaît ici. -

DDP Musique De Chambre À Giverny 06.08.2020

1 Giverny • Vernon • Notre Dame de l’Isle • Saint Pierre d’Autils Normandie Direction artistique Michel Strauss « Musique de Chambre en Normandie » association loi 1901 www.musiqueagiverny.fr 2 Siège social : c/o Yves Druet – 4 rue Lucien Lefrançois – 27 940 Notre Dame de l’Isle Adresse postale: c/o Nathalie Tiberghien – 22 rue Auguste Baudon – 60250 Mouy Siret : 441 555 604 00020 – APE : 9001 Z – Licences : 2-1022714 ; 3-1022713 Président : Philippe HERSANT, compositeur Vice Président : Marcel ERNST, retraité Trésorier : Monique ERNST, retraité Secrétaire : Laurent DUVILLIER, compositeur Equipe Directeur Artistique : Michel Strauss - Port : 06 11 44 44 48 – [email protected] Administration et production : Nathalie Tiberghien - Port. 06 03 21 48 98 – [email protected] Assistantes de production : Audrey Germain, Soline de Warren Communication et relations presse : Simone Strähle - Agence Music ’N Com - Port. 06 60 99 18 24 – [email protected] - Assistée par Zuzanna Wesolowska Actions pédagogiques : Fabienne Radzynski Communication : Pierre Movila - Studio Movila Bénévoles Yveline Dumont, Monique Delemme, Jean Pierre Paul, Yves et Eilish Druet, Muriel Huet, Marie Noëlle Terrasse, Martine Champedal, Patricia Gallucci, Marie-Françoise Druet-Bonis, Catherine Durand, Elena Strauss, Claudine Caussin, Sylvie Moreau, Anne Rosier, Margaret Pâques, Joëlle Müller, Fabienne Radzynski, Michel Muszynski, Mireille Chaleyat Soutiens 2020 Soutiens publics : La Région Normandie, Le Conseil Général de l’Eure, Seine Normandie Agglomération,