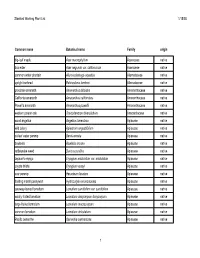

Appendix E Refuge Plant Species List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Biological Report

Biological Report 3093 Beachcomber Drive APN: 065-120-001 Morro Bay, CA Owner: Paul LaPlante Permit #29586 Prepared by V. L. Holland, Ph.D. Plant and Restoration Ecology 1697 El Cerrito Ct. San Luis Obispo, CA 93401 Prepared for: John K Construction, Inc. 110 Day Street Nipomo, CA 93444 [email protected] and Paul LaPlante 1935 Beachcomber Drive Morro Bay, CA 93442 March 5, 2013 BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF 3093 BEACHCOMBER DRIVE, MORRO BAY, CA 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE ...................................................................... 4 LOCATION AND PHYSICAL FEATURES ........................................................ 10 FLORISTIC, VEGETATION, AND WILDLIFE INVENTORY ............................. 11 METHODS ......................................................................................................... 11 RESULTS: FLORA AND VEGETATION ON SITE .......................................... 12 FLORA .............................................................................................................. 12 VEGETATION ..................................................................................................... 13 1. ANTHROPOGENIC (RUDERAL) COMMUNITIES ................................................... 13 2. COASTAL DUNE SCRUB ................................................................................. 15 SPECIAL STATUS PLANT SPECIES .............................................................. -

Thistles of Colorado

Thistles of Colorado About This Guide Identification and Management Guide Many individuals, organizations and agencies from throughout the state (acknowledgements on inside back cover) contributed ideas, content, photos, plant descriptions, management information and printing support toward the completion of this guide. Mountain thistle (Cirsium scopulorum) growing above timberline Casey Cisneros, Tim D’Amato and the Larimer County Department of Natural Resources Weed District collected, compiled and edited information, content and photos for this guide. Produced by the We welcome your comments, corrections, suggestions, and high Larimer County quality photos. If you would like to contribute to future editions, please contact the Larimer County Weed District at 970-498- Weed District 5769 or email [email protected] or [email protected]. Front cover photo of Cirsium eatonii var. hesperium by Janis Huggins Partners in Land Stewardship 2nd Edition 1 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Introduction Native Thistles (Pages 6-20) Barneyby’s Thistle (Cirsium barnebyi) 6 Cainville Thistle (Cirsium clacareum) 6 Native thistles are dispersed broadly Eaton’s Thistle (Cirsium eatonii) 8 across many Colorado ecosystems. Individual species occupy niches from Elk or Meadow Thistle (Cirsium scariosum) 8 3,500 feet to above timberline. These Flodman’s Thistle (Cirsium flodmanii) 10 plants are valuable to pollinators, seed Fringed or Fish Lake Thistle (Cirsium 10 feeders, browsing wildlife and to the centaureae or C. clavatum var. beauty and diversity of our native plant americanum) communities. Some non-native species Mountain Thistle (Cirsium scopulorum) 12 have become an invasive threat to New Mexico Thistle (Cirsium 12 agriculture and natural areas. For this reason, native and non-native thistles neomexicanum) alike are often pulled, mowed, clipped or Ousterhout’s or Aspen Thistle (Cirsium 14 sprayed indiscriminately. -

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

Butterflies and Moths of Brevard County, Florida, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Autographa Gamma

1 Table of Contents Table of Contents Authors, Reviewers, Draft Log 4 Introduction to the Reference 6 Soybean Background 11 Arthropods 14 Primary Pests of Soybean (Full Pest Datasheet) 14 Adoretus sinicus ............................................................................................................. 14 Autographa gamma ....................................................................................................... 26 Chrysodeixis chalcites ................................................................................................... 36 Cydia fabivora ................................................................................................................. 49 Diabrotica speciosa ........................................................................................................ 55 Helicoverpa armigera..................................................................................................... 65 Leguminivora glycinivorella .......................................................................................... 80 Mamestra brassicae....................................................................................................... 85 Spodoptera littoralis ....................................................................................................... 94 Spodoptera litura .......................................................................................................... 106 Secondary Pests of Soybean (Truncated Pest Datasheet) 118 Adoxophyes orana ...................................................................................................... -

The Vascular Flora of the Upper Santa Ana River Watershed, San Bernardino Mountains, California

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281748553 THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE UPPER SANTA ANA RIVER WATERSHED, SAN BERNARDINO MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA Article · January 2013 CITATIONS READS 0 28 6 authors, including: Naomi S. Fraga Thomas Stoughton Rancho Santa Ana B… Plymouth State Univ… 8 PUBLICATIONS 14 3 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Thomas Stoughton Retrieved on: 24 November 2016 Crossosoma 37(1&2), 2011 9 THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE UPPER SANTA ANA RIVER WATERSHED, SAN BERNARDINO MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA Naomi S. Fraga, LeRoy Gross, Duncan Bell, Orlando Mistretta, Justin Wood1, and Tommy Stoughton Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1500 North College Avenue Claremont, California 91711 1Aspen Environmental Group, 201 North First Avenue, Suite 102, Upland, California 91786 [email protected] All Photos by Naomi S. Fraga ABSTRACT: We present an annotated catalogue of the vascular flora of the upper Santa Ana River watershed, in the southern San Bernardino Mountains, in southern California. The catalogue is based on a floristic study, undertaken from 2008 to 2010. Approximately 65 team days were spent in the field and over 5,000 collections were made over the course of the study. The study area is ca. 155 km2 in area (40,000 ac) and ranges in elevation from 1402 m to 3033 m. The study area is botanically diverse with more than 750 taxa documented, including 56 taxa of conservation concern and 81 non-native taxa. Vegetation and habitat types in the area include chaparral, evergreen oak forest and woodland, riparian forest, coniferous forest, montane meadow, and pebble plain habitats. -

Mcgrath State Beach Plants 2/14/2005 7:53 PM Vascular Plants of Mcgrath State Beach, Ventura County, California by David L

Vascular Plants of McGrath State Beach, Ventura County, California By David L. Magney Scientific Name Common Name Habit Family Abronia maritima Red Sand-verbena PH Nyctaginaceae Abronia umbellata Beach Sand-verbena PH Nyctaginaceae Allenrolfea occidentalis Iodinebush S Chenopodiaceae Amaranthus albus * Prostrate Pigweed AH Amaranthaceae Amblyopappus pusillus Dwarf Coastweed PH Asteraceae Ambrosia chamissonis Beach-bur S Asteraceae Ambrosia psilostachya Western Ragweed PH Asteraceae Amsinckia spectabilis var. spectabilis Seaside Fiddleneck AH Boraginaceae Anagallis arvensis * Scarlet Pimpernel AH Primulaceae Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa PH Saururaceae Apium graveolens * Wild Celery PH Apiaceae Artemisia biennis Biennial Wormwood BH Asteraceae Artemisia californica California Sagebrush S Asteraceae Artemisia douglasiana Douglas' Sagewort PH Asteraceae Artemisia dracunculus Wormwood PH Asteraceae Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata Big Sagebrush S Asteraceae Arundo donax * Giant Reed PG Poaceae Aster subulatus var. ligulatus Annual Water Aster AH Asteraceae Astragalus pycnostachyus ssp. lanosissimus Ventura Marsh Milkvetch PH Fabaceae Atriplex californica California Saltbush PH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex lentiformis ssp. breweri Big Saltbush S Chenopodiaceae Atriplex patula ssp. hastata Arrowleaf Saltbush AH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex patula Spear Saltbush AH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex semibaccata Australian Saltbush PH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex triangularis Spearscale AH Chenopodiaceae Avena barbata * Slender Oat AG Poaceae Avena fatua * Wild -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Pala Park Habitat Assessment

Pala Park Bank Stabilization Project: Geotechnical Exploration TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1.0 COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE ATTACHMENTS Biological Report Summary Report (Attachment E-3) Level of Significance Checklist (Attachment E-4) Biological Resources Map (Attachment E-5) Site Photographs (Attachment E-6) SECTION 2.0 HABITAT ASSESSMENT General Site Information ............................................................................................................... 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Existing Conditions ....................................................................................................................... 4 Special Status Resources ............................................................................................................. 8 Other Issues ................................................................................................................................ 14 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................... 14 References .................................................................................................................................. 16 LIST OF TABLES Page 1 Special Status Plant Species Known to Occur in the Vicinity of the Survey Area ........... 10 2 Chaparral Sand-Verbena Populations Observed in the Survey Area ............................. 12 3 Paniculate Tarplant -

Milk Thistle

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Biological Control BIOLOGY AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF EXOTIC T RU E T HISTL E S RACHEL WINSTON , RICH HANSEN , MA R K SCH W A R ZLÄNDE R , ER IC COO M BS , CA R OL BELL RANDALL , AND RODNEY LY M FHTET-2007-05 U.S. Department Forest September 2008 of Agriculture Service FHTET he Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team (FHTET) was created in 1995 Tby the Deputy Chief for State and Private Forestry, USDA, Forest Service, to develop and deliver technologies to protect and improve the health of American forests. This book was published by FHTET as part of the technology transfer series. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/ On the cover: Italian thistle. Photo: ©Saint Mary’s College of California. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for information only and does not constitute an endorsement by the U.S.