Ends of the Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

The American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition Are Vinson Massif (1), Mount Shinn (2), Mount Tyree (3), and Mount Gardner (4)

.' S S \ Ilk 'fr 5 5 1• -Wqx•x"]1Z1"Uavy"fx{"]1Z1"Nnxuxprlau"Zu{vny. Oblique aerial photographic view of part of the Sentinel Range. Four of the mountains climbed by the American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition are Vinson Massif (1), Mount Shinn (2), Mount Tyree (3), and Mount Gardner (4). Mount Os- tenso and Long Gables, also climbed, are among the peaks farther north. tica. Although tentative plans were made to answer The American Antarctic the challenge, it was not until 1966 that those plans began to materialize. In November of that Mountaineering Expedition year, the National Geographic Society agreed to provide major financial support for the undertaking, and the Office of Antarctic Programs of the Na- SAMUEL C. SILVERSTEIN* tional Science Foundation, in view of the proven Rockefeller University capability, national representation, and scientific New York, N.Y. aims of the group, arranged with the Department of Defense for the U.S. Naval Support Force, A Navy LC-130 Hercules circled over the lower Antarctica, to provide the logistics required. On slopes of the Sentinel Range, then descended, touched December 3, the climbing party, called the Ameri- its skis to the snow, and glided to a stop near 10 can Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition, assem- waiting mountaineers and their equipment. Twenty- bled in Los Angeles to prepare for the unprece- five miles to the east, the 16,860-foot-high summit dented undertaking. of Vinson Massif, highest mountain in Antarctica, glistened above a wreath of gray cloud. Nearby The Members were Mount Tyree, 16,250 feet, second highest The expedition consisted of 10 members selected mountain on the Continent; Mount Shinn, about 16,- by the American Alpine Club. -

A News Bulletin New Zealand, Antarctic Society

A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND, ANTARCTIC SOCIETY INVETERATE ENEMIES A penguin chick bold enough to frighten off all but the most severe skua attacks. Photo: J. T. Darby. Vol. 4. No.9 MARCH. 1967 AUSTRALIA WintQr and Summer bAsts Scott Summer ila..se enly t Hal'ett" Tr.lnsferrea ba.se Will(,t~ U.S.foAust T.mporArily nen -eper&tianaJ....K5yow... •- Marion I. (J.A) f.o·W. H.I.M.S.161 O_AWN IY DEPARTMENT OF LANDS fa SU_VEY WILLINGTON) NEW ZEALAND! MAR. .•,'* N O l. • EDI"'ON (Successor to IIAntarctic News Bulletin") Vol. 4, No.9 MARCH, 1967 Editor: L. B. Quartermain, M.A., 1 Ariki Road, Wellington, E.2, ew Zealand. Assistant Editor: Mrs R. H. Wheeler. Business Communications, Subscriptions, etc., to: Secretary, ew Zealand Antarctic Society, P.O. Box 2110, Wellington, .Z. CONTENTS EXPEDITIONS Page New Zealand 430 New Zealand's First Decade in Antarctica: D. N. Webb 430 'Mariner Glacier Geological Survey: J. E. S. Lawrence 436 The Long Hot Summer. Cape Bird 1966-67: E. C. Young 440 U.S.S.R. ...... 452 Third Kiwi visits Vostok: Colin Clark 454 Japan 455 ArgenHna 456 South Africa 456 France 458 United Kingdom 461 Chile 463 Belgium-Holland 464 Australia 465 U.S.A. ...... 467 Sub-Antarctic Islands 473 International Conferences 457 The Whalers 460 Bookshelf ...... 475 "Antarctica": Mary Greeks 478 50 Years Ago 479 430 ANTARCTI'C March. 1967 NEW ZEALAND'S FIRST DECAD IN ANTARCTICA by D. N. Webb [The following article was written in the days just before his tragic death by Dexter Norman Webb, who had been appointed Public ReLations Officer, cott Base, for the 1966-1967 summer. -

Antarctic.V12.4.1991.Pdf

500 lOOOMOTtcn ANTARCTIC PENINSULA s/2 9 !S°km " A M 9 I C j O m t o 1 Comandante Ferraz brazil 2 Henry Arctowski polano 3 Teniente Jubany Argentina 4 Artigas uruouav 5 Teniente Rodotfo Marsh emu BeHingshausen ussr Great WaD owa 6 Capstan Arturo Prat ck«.e 7 General Bernardo O'Higgins cmiu 8 Esperanza argentine 9 Vice Comodoro Marambio Argentina 10 Palmer usa 11 Faraday uk SOUTH 12 Rothera uk SHETLAND 13 Teniente Carvajal chile 14 General San Martin Argentina ISLANDS JOOkm NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY MAP COPYRIGHT Vol. 12 No. 4 Antarctic Antarctic (successor to "Antarctic News Bulletin") Vol. 12 No.4 Contents Polar New Zealand 94 Australia 101 Pakistan 102 United States 104 West Germany 111 Sub-Antarctic ANTARCTIC is published quarterly by Heard Island 116 theNew Zealand Antarctic Society Inc., 1978. General ISSN 0003-5327 Antarctic Treaty 117 Greenpeace 122 Editor: Robin Ormerod Environmental database 123 Please address all editorial inquiries, contri Seven peaks, seven months 124 butions etc to the Editor, P.O. Box 2110, Wellington, New Zealand Books Antarctica, the Ross Sea Region 126 Telephone (04) 791.226 International: +64-4-791-226 Shackleton's Lieutenant 127 Fax: (04)791.185 International: + 64-4-791-185 All administrative inquiries should go to the Secretary, P.O. Box 1223, Christchurch, NZ Inquiries regarding Back and Missing issues to P.O. Box 1223, Christchurch, N.Z. No part of this publication may be reproduced in Cover : Fumeroles on Mt. Melbourne any way, without the prior permission of the pub lishers. Photo: Dr. Paul Broddy Antarctic Vol. -

Dr. William Long 28 April 2001 Karen Brewster Interviewer (Begin Tape 1

Dr. William Long 28 April 2001 Karen Brewster Interviewer (Begin Tape 1 - Side A) (000) KB: This is Karen Brewster and today is Saturday, April 28th, 2001. I'm here at the home of William Long in Palmer, Alaska, and we're going to be talking about his Antarctic and Arctic experiences and career. So, thank you very much for having me here. WL: Well, it's great to have you here Karen. It's an opportunity that I'm happy to participate in. KB: Well, good. And this is for the Byrd Polar Research Center at Ohio State. You very nicely wrote everything down and started to answer the questions, but I'm going to go through it so we can talk about things. WL: And I won't have those in my hand, so you can compare my answers to your questions. KB: So, let's just start with when and where you were born and a little bit about your childhood. 2 WL: I was born August 18th, 1930, in Minot, North Dakota. My father was a schoolteacher and he had taken his first job at Belva, which is near Minot, and it was that year that I was born. It was one of the coldest years they had experienced and perhaps that influences my interest in cold areas. But, my mother has told me that it was the year that it was below 50 below there and the cows froze in the field across from the home they lived in. We only lived there one year and from that point, we moved to California when I was one year old, and essentially I was raised in California, until I began adult life. -

Mem170-Bm.Pdf by Guest on 30 September 2021 452 Index

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] acacamite, 437 anticlines, 21, 385 Bathyholcus sp., 135, 136, 137, 150 Acanthagnostus, 108 anticlinorium, 33, 377, 385, 396 Bathyuriscus, 113 accretion, 371 Antispira, 201 manchuriensis, 110 Acmarhachis sp., 133 apatite, 74, 298 Battus sp., 105, 107 Acrotretidae, 252 Aphelaspidinae, 140, 142 Bavaria, 72 actinolite, 13, 298, 299, 335, 336, 339, aphelaspidinids, 130 Beacon Supergroup, 33 346 Aphelaspis sp., 128, 130, 131, 132, Beardmore Glacier, 429 Actinopteris bengalensis, 288 140, 141, 142, 144, 145, 155, 168 beaverite, 440 Africa, southern, 52, 63, 72, 77, 402 Apoptopegma, 206, 207 bedrock, 4, 58, 296, 412, 416, 422, aggregates, 12, 342 craddocki sp., 185, 186, 206, 207, 429, 434, 440 Agnostidae, 104, 105, 109, 116, 122, 208, 210, 244 Bellingsella, 255 131, 132, 133 Appalachian Basin, 71 Bergeronites sp., 112 Angostinae, 130 Appalachian Province, 276 Bicyathus, 281 Agnostoidea, 105 Appalachian metamorphic belt, 343 Billingsella sp., 255, 256, 264 Agnostus, 131 aragonite, 438 Billingsia saratogensis, 201 cyclopyge, 133 Arberiella, 288 Bingham Peak, 86, 129, 185, 190, 194, e genus, 105 Archaeocyathidae, 5, 14, 86, 89, 104, 195, 204, 205, 244 nudus marginata, 105 128, 249, 257, 281 biogeography, 275 parvifrons, 106 Archaeocyathinae, 258 biomicrite, 13, 18 pisiformis, 131, 141 Archaeocyathus, 279, 280, 281, 283 biosparite, 18, 86 pisiformis obesus, 131 Archaeogastropoda, 199 biostratigraphy, 130, 275 punctuosus, 107 Archaeopharetra sp., 281 biotite, 14, 74, 300, 347 repandus, 108 Archaeophialia, -

Spring Outfitter 2012 FYI Mechanical - 'Clean', Without Phototags

The original expediTion ouTfiTTer Spring Outfitter 2012 FYI Mechanical - 'clean', without phototags 01/13/12_11:01AM FREE SHIPPING Catalog in-home 2/6/20 12 On yOur purchase Of $75 Or mOre. See inSide for detailS. 2012 OuTfITTEr BOOK: volume 2, no. 1 CD12_1_048A_001.pdf ThE OuTfITTEr BOOK + EXPEDITION TravEl: JOrDaN uPrIsINg + ThE ThIrD DIscIPlINE Of guIDINg sPrINg + KayaK BrazIl: amazONIaN WaTErfalls + JaKE NOrTON TaKEs ON challENgE 21 NO CHANGES CAN BE MADE AT THIS TIME. fEaTurED INTErvIEWs: + caroline george + dave HaHn + melissa arnot + ben stookesberry For changes to the distribution list, please call Mary Ward-Smith at extension 6472. Color is not accurate and is to be used as a guide only. The pages can be viewed by clicking on the page number desired in the Bookmark column. Womens 6 - 19, 24/25, 28/29, 36/37, 42/43, 44, 48 Field & Gear 14/15, 20 - 25, 30/31, 34 - 37, 40 - 43 Mens 6 - 21, 28 - 31, 34/35, 40/41, 45, 48 Kids 46/47 Marketing Components At the end PRSRT STD Prices expire 4/29/12 U.S. POSTAGE PO Box 7001, Groveport, OH 43125 PAID EDDIE BAUER Printed in USA Caring for the environment is one of our core values. The paper in this catalog is certified to contain fiber from responsibly managed sources. Please pass this catalog on or recycle it. THE MICROTHERM™ DOWN VEST NEW CORE FOCUS FROM OUR LIGHTEST, WARMEST LAYER EVER. 800 DOWN FILL MICROTHERM DOWN VEST “THE LIGHTEST, WARMEST THINGS ON EARTH.”® Incredibly thin and lightweight, but with all the insulating warmth of 800 fill Premium European Goose Down in a streamlined, non-puffy silhouette. -

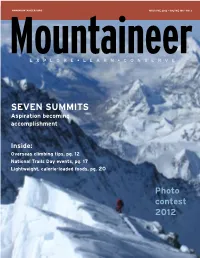

SEVEN SUMMITS Aspiration Becoming Accomplishment

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MAY/JUNE 2012 • VOLUME 106 • NO. 3 MountaineerE X P L O R E • L E A R N • C O N S E R V E SEVEN SUMMITS Aspiration becoming accomplishment Inside: Overseas climbing tips, pg. 12 National Trails Day events, pg. 17 Lightweight, calorie-loaded foods, pg. 20 Photo contest 2012 inside May/June 2012 » Volume 106 » Number 3 12 Cllimbing Abroad 101 Enriching the community by helping people Planning your first climb abroad? Here are some tips explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest. 14 Outdoors: healthy for the economy A glance at the value of recreation and preservation 12 17 There is a trail in need calling you Help out on National Trails Day at one of these events 18 When you can’t hike, get on a bike Some dry destinations for National Bike Month 21 Achieving the Seven Summits Two Olympia Mountaineers share their experiences 8 conservation currents New Alpine Lakes stewards: Weed Watchers 18 10 reachING OUT Great people, volunteers and partners bring success 16 MEMbERShIP matters A hearty thanks to you, our members 17 stepping UP Swapping paddles for trail maintenance tools 24 impact GIVING 21 Mountain Workshops working their magic with youth 32 branchING OUT News from The Mountaineers Branches 46 bOOkMARkS New Mountaineers release: The Seven Summits 47 last word Be ready to receive the gifts of the outdoors the Mountaineer uses . DIscoVER THE MOUntaINEERS If you are thinking of joining—or have joined and aren’t sure where to start—why not attend an information meeting? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine (page 32) for times and locations for each of our seven branches. -

Climbing to Mt.Vinson 4897M, Antarctica

Climbing Mt.Vinson 4897m, Antarctica Regions: Antarctica Objects: Vinson (4897m) Activities: Mountaineering Program's difficulty: 4.5, mid easy ( technical 3 + altitudinal 1.5 ) Group: From 3 Price: 45 900 USD Dates ( Days 16 / Nights 15 ) 2021: November 23 - December 08 ( Rostovtsev Artem ) December 04 - December 19 ( Rostovtsev Artem ) December 15 - December 30 ( Rostovtsev Artem ) December 26 - January 10 ( Rostovtsev Artem ) 2022: January 06 - January 21 ( Rostovtsev Artem ) Trip overview Santiago, Chile - Punta Arenas - Union Glacier - Vinson Massif Base Camp – Summit - Vinson Massif BC – Union Glacier – Punta Arenas - Santiago, Chile Why go there? An expedition to Vinson Peak is often called the “Key to the 7 Summits”. The mountain itself does not present serious technical problems, but it is very difficult to even reach it. Mount Vinson is very remote and therefore any expedition is very expensive. The rewards is great: climbing the highest summit of Antarctica is an incredible experience in itself and for many the final step to reaching their 7 summits goal. A trip to Vinson Massif is exceptionally interesting, beautiful and prestigious. So far very few people have done it and for most, it is the highlight of their "7 summits quest". Our program starts in Punta Arenas (Chile). From there, a special Ilyushin-76 aircraft takes us to the Union Glacier camp in Antarctica and lands on the ice (with wheels). From the Union Glacier camp, a small ski-equipped plane brings us to Vinson Massif Base Camp (BC), where we pitch our tents. From here we start the ascent of Mount Vinson, using another 2 intermediate camps before attempting to reach the summit of Mount Vinson, the highest point of Antarctica. -

Itinerary Changes 2021

ITINERARY CHANGES 2021 Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic ALE has made some adjustments to our operations in order to ensure the well-being of our guests and staff and to minimize the risk of bringing the infection into Antarctica. Below, you will find how our itineraries across all of our experiences for the 2021-22 season will be modified. Punta Arenas • You will be required to arrive in Punta Arenas 4 nights prior to your departure. • Welcome and Safety Briefings will be done virtually. • There will be no fitting periods for Rental Clothing in the Punta Arenas office, instead clothing will be picked up at a specified location and time. Further information will be given upon arrival in Punta Arenas. • Your Gear Checks will be done virtually and we will explain to you how this will be done once you arrive in Punta Arenas. • Flight Check in and Baggage Drop Off will be done using COVID-19 safe practices and you will receive more information on how this will be done on arrival in Punta Arenas. • You will be required to complete and sign a COVID-19 Declaration prior to your departure. Antarctica ALE has developed COVID-19 management procedures for Antarctica. These will be covered in your briefings in Punta Arenas and on arrival at Union Glacier. Please visit our FAQ for more detailed information on ALE’s COVID-19 Management Strategy https:// bit.ly/3g5e4ql MOUNT VINSON ANTARCTICA’S HIGHEST PEAK Imagine yourself on the summit of Mount ascent due to the challenges of accessing Vinson 16,050 ft (4892 m), the highest its remote location. -

Mt. Vinson (16,067 Ft/4,897 M) Planning Package

Mt. Vinson (16,067 ft/4,897 m) Planning Package Photo by Dave Morton Climber Information Photo by Dave Morton Keep in Touch Flight Information As a member of our Mt. Vinson team we encourage you to contact Given the nature of the flight, there may be delays getting in/ us with any questions as our intent is to provide personal attention out of Antarctica. If we are delayed in Punta Arenas, those are to your preparation needs. While this document will answer many “free” days to tour the city. Alpine Ascents does not provide food, of your questions, we enjoy hearing about your specific interests transport and hotels during your stay in Punta Arenas. and look forward to making the pre-trip planning and training an exciting part of the journey. Please take the time to read this Flight reservations for your climb should be made as soon as document in full. possible. Alpine Ascents uses the services of Charles Mulvehill at Scan East West Travel: (800) 727-2157 or (206) 623-2157. He is very Alpine Ascents Seattle: (206) 378-1927 familiar with our International and Domestic Programs and offers competitive prices on all domestic/international flights. Paperwork We highly recommend using our travel agent as he can best facilitate changes. Flights back to the USA usually need to be Please make sure you complete and return the following changed (as flights to/from Antarctica are subject to delay). If you paperwork as soon as possible. This information assists us in use our travel agent we may be able to call ahead via satellite procuring permits and making final hotel reservations. -

Explorer's Gazette

EEXXPPLLOORREERR’’SS GGAAZZEETTTTEE Uniting all OAE’s in Perpetuating the Memory of U.S. Navy Operations in Antarctica Volume 4, Issue 2 Old Antarctic Explorers Association, Inc Spring 2004 YOG-34 YOG-34 Crew on arrival at McMurdo December 1955. Father Time 34 was the radio callsign for YOG-34. Standing L/R: RMSN John Zegers, ENC Raftery, MM1 Harold Lundy, Unknown, CMCN Michael Clay, AN John Tallon, “Moon Man” Clarko, Unknown, UTCN R.J. Brown, “Balay” Campbell, “Mule” Miller, Mess Cook Creacy, Unknown, Unknown, Unknown, SWCN Colon Roberts, “Nig Wig” Merrell. Knelling L/R: MM3 B.B. Duke, AN Charles Olivera, Jr, “Shaggy Chops #2” Rogers, LT Jehu Blades (CO), CS2 Raymond Spiers, AM3 Aubrey Weems, L.V. “Flags” Thomas, UTCN Donald Scott See Related Story on Page 15 E X P L O R E R ‘ S G A Z E T T E V O L U M E 4, I S S U E 2 S P R I N G 2 0 0 4 PRESIDENT’S CORNER CHAPLAIN’S CORNER Jim Eblen — OAEA President Cecil D. Harper — OAEA Chaplain TO ALL OAE’S — Hope this finds everyone in good There is nothing health and looking forward to Spring. more stirring and The next Symposium/Reunion scheduled to be held in pleasant than to feel Oxnard CA on January 26, 27, & 28, 2005 is moving right that life has been along. I traveled to Oxnard in late January and met with Jim good and that good Maddox, chairman, and his Symposium/Reunion committee things are ahead.