Dr. William Long 28 April 2001 Karen Brewster Interviewer (Begin Tape 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property Owners' Willingness to Pay for Restoring Impaired Waters

ii Property Owners’ Willingness To Pay For Restoring Impaired Lakes: A Survey In Two Watersheds of the Upper Mississippi River Basin This study was conducted on behalf of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Sauk River Watershed District, and City of Lake Shore, Minnesota by Patrick G. Welle, Ph.D.* Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies Bemidji State University Bemidji, Minnesota and Jim Hodgson Upper Mississippi River Basin Coordinator North Central Regional Office Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Brainerd – Baxter, Minnesota October, 2008 wq-b4-01 iii Acknowledgements Assistance with the mail survey and interviews was provided by Laura Peschges, Bridget Sitzer, Emily Seely, Asher Kingery, Scott Gullicksrud and Brent Hennen. The format and certain sections of this report are adapted from three previous reports to the Legislative Commission on Minnesota Resources: one by the lead author “Multiple Benefits from Agriculture: A Survey of Public Values in Minnesota” (2001) and two by the lead author and two co-authors, Daniel Hagen and James Vincent: “Economic Benefits of Reducing Toxic Air Pollution: A Minnesota Study” (1992) and “Economic Benefits of Reducing Mercury Deposition in Minnesota” (1998). Additionally the authors would like to thank the following staff of the MPCA North Central Office staff: Bev Welle for her assistance in setting up the advisory committees, typing and copying the many drafts of the survey, Bonnie Finnerty for review and comments of the survey first as the Crow Wing County Planner and then as a staff member of the MPCA; Maggie Leach, Bob McCarron, and David Christopherson for their editorial and content comments; Greg Van Eeckhout, for assistance in the development of the description of the current conditions for both watersheds; and Pete Knutson for the GIS and mapping assistance. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

The American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition Are Vinson Massif (1), Mount Shinn (2), Mount Tyree (3), and Mount Gardner (4)

.' S S \ Ilk 'fr 5 5 1• -Wqx•x"]1Z1"Uavy"fx{"]1Z1"Nnxuxprlau"Zu{vny. Oblique aerial photographic view of part of the Sentinel Range. Four of the mountains climbed by the American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition are Vinson Massif (1), Mount Shinn (2), Mount Tyree (3), and Mount Gardner (4). Mount Os- tenso and Long Gables, also climbed, are among the peaks farther north. tica. Although tentative plans were made to answer The American Antarctic the challenge, it was not until 1966 that those plans began to materialize. In November of that Mountaineering Expedition year, the National Geographic Society agreed to provide major financial support for the undertaking, and the Office of Antarctic Programs of the Na- SAMUEL C. SILVERSTEIN* tional Science Foundation, in view of the proven Rockefeller University capability, national representation, and scientific New York, N.Y. aims of the group, arranged with the Department of Defense for the U.S. Naval Support Force, A Navy LC-130 Hercules circled over the lower Antarctica, to provide the logistics required. On slopes of the Sentinel Range, then descended, touched December 3, the climbing party, called the Ameri- its skis to the snow, and glided to a stop near 10 can Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition, assem- waiting mountaineers and their equipment. Twenty- bled in Los Angeles to prepare for the unprece- five miles to the east, the 16,860-foot-high summit dented undertaking. of Vinson Massif, highest mountain in Antarctica, glistened above a wreath of gray cloud. Nearby The Members were Mount Tyree, 16,250 feet, second highest The expedition consisted of 10 members selected mountain on the Continent; Mount Shinn, about 16,- by the American Alpine Club. -

1 Grade Fluency Folder

First Grade 0 st 1 Grade Fluency Folder Dear Parent(s), We have created this Fluency Folder to help your child develop effective reading skills. Your child will need and use this folder throughout the school year. Please keep this folder safe . It will be your responsibility to keep this folder intact. It will not be replaced . This folder will need to be brought to school and taken home on a daily basis. Below is a list of ways we will use this reading folder: 1. Sight Words: These lists contain the first 100 and 200 words from the Fry Instant Word Lists (1980).The students will be required to know how to read the words on each set. The daily practice is designed to help the students build reading fluency. Begin by practicing Set 1. The students will be tested weekly for mastery. Mastery is being able to read each word in a second (see it, say it) . The student will move on to the next set when at least 75% (20 words) has been mastered. When the child moves into the next set please continue to review any words that have not been mastered from the previous sets. This is part of the daily homework. Please help your child to achieve this goal. These words may be written on sentence strips to be practiced at home. 2. Sight Word Phrases: In addition to Sight Word Lists, there are Sight Word Phrases. Please follow the directions indicated for Sight Word Lists. As with the Sight Word List, please remember that the student will move on to the next set when at least 75% (20 phrases) has been mastered. -

Antarctic.V12.4.1991.Pdf

500 lOOOMOTtcn ANTARCTIC PENINSULA s/2 9 !S°km " A M 9 I C j O m t o 1 Comandante Ferraz brazil 2 Henry Arctowski polano 3 Teniente Jubany Argentina 4 Artigas uruouav 5 Teniente Rodotfo Marsh emu BeHingshausen ussr Great WaD owa 6 Capstan Arturo Prat ck«.e 7 General Bernardo O'Higgins cmiu 8 Esperanza argentine 9 Vice Comodoro Marambio Argentina 10 Palmer usa 11 Faraday uk SOUTH 12 Rothera uk SHETLAND 13 Teniente Carvajal chile 14 General San Martin Argentina ISLANDS JOOkm NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY MAP COPYRIGHT Vol. 12 No. 4 Antarctic Antarctic (successor to "Antarctic News Bulletin") Vol. 12 No.4 Contents Polar New Zealand 94 Australia 101 Pakistan 102 United States 104 West Germany 111 Sub-Antarctic ANTARCTIC is published quarterly by Heard Island 116 theNew Zealand Antarctic Society Inc., 1978. General ISSN 0003-5327 Antarctic Treaty 117 Greenpeace 122 Editor: Robin Ormerod Environmental database 123 Please address all editorial inquiries, contri Seven peaks, seven months 124 butions etc to the Editor, P.O. Box 2110, Wellington, New Zealand Books Antarctica, the Ross Sea Region 126 Telephone (04) 791.226 International: +64-4-791-226 Shackleton's Lieutenant 127 Fax: (04)791.185 International: + 64-4-791-185 All administrative inquiries should go to the Secretary, P.O. Box 1223, Christchurch, NZ Inquiries regarding Back and Missing issues to P.O. Box 1223, Christchurch, N.Z. No part of this publication may be reproduced in Cover : Fumeroles on Mt. Melbourne any way, without the prior permission of the pub lishers. Photo: Dr. Paul Broddy Antarctic Vol. -

Adjectives Name Describes

Name Date Reteach 1 Sentences RULES •A sentence is a group of words that expresses a complete thought. A sentence names the person or thing you are talking about. It also tells what happened. SENTENCE: I received a letter from my pen pal. • A sentence fragment is a group of words that does not express a complete thought. FRAGMENT: Friends for a long time. Read each group of words. Circle yes if the words make a sentence. Circle no if they are a sentence fragment. 1. Maritza is my favorite pen pal. yes no 2. Lives in Puerto Rico. yes no 3. I have been writing to Maritza for two years. yes no 4. She is four months older than me. yes no 5. Tall girl with green eyes. yes no 6. We are both in the fourth grade. yes no 7. I visited Puerto Rico with my family. yes no 8. Stayed at Maritza’s house. yes no 9. Maritza introduced me to all her friends. yes no 10. Sometimes her brother. yes no McGraw-Hill School Division McGraw-Hill Language Arts At Home: Choose a sentence fragment from this page. Add Grade 4, Unit 1, Sentences, words to make it a sentence. Write your new sentence on a 10 pages 2–3 separate sheet of paper. 1 Name Date Reteach 2 Declarative and Interrogative Sentences RULES • A declarative sentence makes a statement. My pen pal lives in Japan. It begins with a capital letter. It ends with a period. • An interrogative sentence asks a question. Where does your pen pal live? It begins with a capital letter. -

Introduction

Introduction Dear Future McAuliffe Scholars, This anthology is a collection of narratives written by the sixth graders at Christa McAuliffe Charter School; the same sixth graders who were last year in your shoes. These narratives are about the transition from elementary school to McAuliffe. This collection displays many different stories about students joining a new community. It is made interesting by the diversity all of the scholars bring. Throughout the fall trimester, students have been working on crafting their narratives while being guided by various learning targets. The long term target students have been working on is, “I can craft a narrative about my place in the McAuliffe community.” As we crafted our narratives, we learned to use transition words and figurative language to enrich our work. The purpose of this expedition was to build a stronger community and make connections to other people. We hope that the readers of this anthology will know now that joining a new community may be hard at first, but “bridges” are built more quickly than you may expect. We hope that after reading this anthology you will feel more excited to come to McAuliffe. Sincerely, Class of 2017 Introduction by: Ashna Hille, Alexa Hughes, Marian Rookey, Laszlo Bernstein, Stephen Eckelkamp, and Daniel Xu 1 2 This anthology is dedicated to: The McAuliffe Admissions team, and all students of McAuliffe past, present, and future. 3 4 Left to Right: Will D., Dasan J., Terrence O., Peter M. 5 Dasan J. Mrs. Richards’s Crew November 2014 “PLING!”, beeped the sound of my mother’s e-mail notification. -

2019 Winter NASIS Nebraska Annual Social Indicators Survey

2019 Winter NASIS Nebraska Annual Social Indicators Survey Life In Nebraska 6. Researchers grow cultured meat from cells without slaughtering animals. They are trying to develop 1. Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with cultured meat for the general public. We have some living in Nebraska? questions for you about cultured meat. Very satisfied Don’t Yes No Somewhat satisfied know Neutral a. Have you ever heard of Somewhat dissatisfied cultured meat? Very dissatisfied b. Would you like to learn more about cultured 2. All in all, do you think things in Nebraska are meat? generally headed in the right direction or the wrong c. Would you be willing to direction? eat cultured meat? Right direction Wrong direction 7. Do you think that researchers should work on making Unsure cultured meat available and affordable for the following groups? 3. All in all, do you think things in the country as a Don’t Yes No whole are generally headed in the right direction or know the wrong direction? a. The general public in Right direction grocery stores Wrong direction b. Public school children Unsure c. People in nursing homes Food Science d. People in remote areas, 4. Does each of the following statements describe you? such as rural or tribal Don’t communities or Yes No know astronauts on the moon a. I would share my health e. People with limited information with food access to meat, such as service members on manufactures if they could create food that is submarines just right for me. f. People with health issues b. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title Title - Be 02 Johnny Cash 03-Martina McBride 05 LeAnn Rimes - Butto Folsom Prison Blues Anyway How Do I Live - Promiscuo 02 Josh Turner 04 Ariana Grande Ft Iggy Azalea 05 Lionel Richie & Diana Ross - TWIST & SHO Why Don't We Just Dance Problem Endless Love (Without Vocals) (Christmas) 02 Lorde 04 Brian McKnight 05 Night Ranger Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer Royals Back At One Sister Christian Karaoke Mix (Kissed You) Good Night 02 Madonna 04 Charlie Rich 05 Odyssey Gloriana Material Girl Behind Closed Doors Native New Yorker (Karaoke) (Kissed You) Good Night Wvocal 02 Mark Ronson Feat.. Bruno Mars 04 Dan Hartman 05 Reba McIntire Gloriana Uptown Funk Relight My Fire (Karaoke) Consider Me Gone 01 98 Degress 02 Ricky Martin 04 Goo Goo Dolls 05 Taylor Swift Becouse Of You Livin' La Vida Loca (Dance Mix) Slide (Dance Mix) Blank Space 01 Bob Seger 02 Robin Thicke 04 Heart 05 The B-52's Hollywood Nights Blurred Lines Never Love Shack 01 Bob Wills And His Texas 02 Sam Smith 04 Imagine Dragons 05-Martina McBride Playboys Stay With Me Radioactive Happy Girl Faded Love 02 Taylor Swift 04 Jason Aldean 06 Alanis Morissette 01 Celine Dion You Belong With Me Big Green Tractor Uninvited (Dance Mix) My Heart Will Go On 02 The Police 04 Kellie Pickler 06 Avicci 01 Christina Aguilera Every Breath You Take Best Days Of Your Life Wake Me Up Genie In A Bottle (Dance Mix) 02 Village People, The 04 Kenny Rogers & First Edition 06 Bette Midler 01 Corey Hart YMCA (Karaoke) Lucille The Rose Karaoke Mix Sunglasses At Night Karaoke Mix 02 Whitney Houston 04 Kim Carnes 06 Black Sabbath 01 Deborah Cox How Will I Know Karaoke Mix Bette Davis Eyes Karaoke Mix Paranoid Nobody's Supposed To Be Here 02-Martina McBride 04 Mariah Carey 06 Chic 01 Gloria Gaynor A Broken Wing I Still Believe Dance Dance Dance (Karaoke) I Will Survive (Karaoke) 03 Billy Currington 04 Maroon 5 06 Conway Twitty 01 Hank Williams Jr People Are Crazy Animals I`d Love To Lay You Down Family Tradition 03 Britney Spears 04 No Doubt 06 Fall Out Boy 01 Iggy Azalea Feat. -

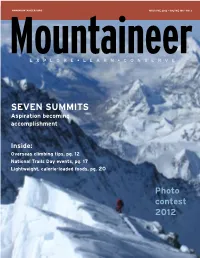

SEVEN SUMMITS Aspiration Becoming Accomplishment

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MAY/JUNE 2012 • VOLUME 106 • NO. 3 MountaineerE X P L O R E • L E A R N • C O N S E R V E SEVEN SUMMITS Aspiration becoming accomplishment Inside: Overseas climbing tips, pg. 12 National Trails Day events, pg. 17 Lightweight, calorie-loaded foods, pg. 20 Photo contest 2012 inside May/June 2012 » Volume 106 » Number 3 12 Cllimbing Abroad 101 Enriching the community by helping people Planning your first climb abroad? Here are some tips explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest. 14 Outdoors: healthy for the economy A glance at the value of recreation and preservation 12 17 There is a trail in need calling you Help out on National Trails Day at one of these events 18 When you can’t hike, get on a bike Some dry destinations for National Bike Month 21 Achieving the Seven Summits Two Olympia Mountaineers share their experiences 8 conservation currents New Alpine Lakes stewards: Weed Watchers 18 10 reachING OUT Great people, volunteers and partners bring success 16 MEMbERShIP matters A hearty thanks to you, our members 17 stepping UP Swapping paddles for trail maintenance tools 24 impact GIVING 21 Mountain Workshops working their magic with youth 32 branchING OUT News from The Mountaineers Branches 46 bOOkMARkS New Mountaineers release: The Seven Summits 47 last word Be ready to receive the gifts of the outdoors the Mountaineer uses . DIscoVER THE MOUntaINEERS If you are thinking of joining—or have joined and aren’t sure where to start—why not attend an information meeting? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine (page 32) for times and locations for each of our seven branches. -

Sluts of the Block (30171:30226) Well Your Ass Is So Tight, You're the Sluts of the Block

Project: FINNNNALLLL PROJECT Report created by wtd220 on 12/14/2017 Codes Report All (393) codes ○ abuse Created by Whitney Davis on 12/13/2017 1 Groups: Rape 29 Quotations: D 2: Adolescents - 2:57 Abused our trust and broke our ties (36255:36289) Abused our trust and broke our ties D 9: Bad Religion - 9:49 I refuse to abuse what is kind to the Muse, (23398:23440) I refuse to abuse what is kind to the Muse, D 11: Black Flag lyrics - 11:55 It's no use I can't take no more abuse (1594:1631) It's no use I can't take no more abuse D 11: Black Flag lyrics - 11:56 We are tired of your abuse (8218:8243) We are tired of your abuse D 11: Black Flag lyrics - 11:57 We are tired of your abuse (8563:8588) We are tired of your abuse D 11: Black Flag lyrics - 11:58 We are tired of your abuse (8621:8646) We are tired of your abuse D 11: Black Flag lyrics - 11:59 We are tired of your abuse (8934:8959) We are tired of your abuse D 14: Circle Jerks - 14:43 Abuse that stuff you'll only loose (30901:30934) Abuse that stuff you'll only loose D 15: Corrosion of Conformity - 15:5 Burned limbless victims of power's abuses (226:266) Burned limbless victims of power's abuses D 17: D.O.A. - 17:29 into the badlands, the white man came. killing out of fear, what they… (21076:21867) into the badlands, the white man came. -

Lent & Easter Customs 2

Part Two Ways Families Celebrate Lent and Easter 2011 SURVEY RESULTS LENTEN PRACTICES FOR ADULTS AND CHILDREN, RECIPES, AND MORE Compiled by Catholic Heritage Curricula www.chcweb.com As a parent, which Lenten activity/prayer/practice is the most helpful to your own spiritual growth and renewal? Doing sacrifi cial things as a family is helpful to We prac ce the “Our Father” during Lent each me. It is like holding hands through life. It’s a per- day. It helps the li le ones to learn the words. sonifi ca on of our Lord suff ering with us as we It also gives everyone a chance to ask ques- are met with each day. ons about what the words mean especially if Renee in Belleville, WI they don’t understand. Some mes the kids ask ques ons that I’m able to answer right away and During Lent, I try to pray the rosary more dili- others I have to research. The ques ons help gently. At the beginning of the Lenten season me with spiritual growth because it gives me a it seems so labored to try to squeeze it into my chance to think about Our Lord for a longer pe- already busy schedule of raising 3 young children, riod during my busy day. but by the end of Lent it is like second nature. I Tiff any in Disputanta, VA love that. I feel so much closer to Jesus and Our Mother Mary by the me Easter is here. Trying to keep all of Lent austere - no celebra ng Lindsey in Boerne, TX if possible, trying to turn off as much interior and exterior noise as possible, and par cularly trying The Rosary and prayer to Padre Pio help to calm to keep the Triduum as solemn a me as the li le my soul and prepare for motherhood as a daily ones will allow.