The Romanian Post-Avant-Gardes. Between Influence and Equivalence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serban Foarta

Traducerea textelor străine (nu mai puţin aceea,-n vers şi rimă, a basmului lui Charles Perrault) îi aparţine autorului antologiei, Şerban Foarţă • Excepţie fac, în ordinea intrării în scenă, fragmentele din Sei Şōnagon, Însemnări de căpătâi, trad. Stanca Cionca; Rudolf Kassner, Vrăjitorul, trad. Mihnea Moroianu; E.T.A. Hoffmann, Părerile despre viaţă ale motanului Murr, trad. Valeria Sadoveanu; Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, Viaţa mea cu Mozart, trad. Lidia Bodea; Michelangelo Buonarroti, Sonetul V, trad. Eta Boeriu; Alan Brownjohn, Poem cu pisică rea, trad. Denisa Comănescu • La tălmăcirea poeziilor maghiarofone (şi anume, Pisicuţa-Piticuţa de Móricz Zsigmond, respectiv O cheamă Pis-Pis de Eszteró István) şi-a dat concursul Ildikó Gábos-Foarţă • Întreaga noastră gratitudine, în fine, tuturor celor care ne-au acordat copyrighturile de rigoare. Coperta: ANGELA ROTARU Ilustraţia copertei: ANDREI GAMARŢ ISBN 978-973-50-5054-2 Descrierea CIP este disponibilă la Biblioteca Naţională a României. Dario Bellezza, Miosotis, Sfortunata, La gattità din volumul Io, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1983 © Heirs of Dario Bellezza Jorge Luis Borges, Beppo, A un Gato © Maria Kodama, 1995, used by permission of The Wylie Agency (UK) Limited Alan Brownjohn, A bad cat poem © Alan Brownjohn Maurice Carême, Le chat et le soleil din volumul L’arlequin; Il a neigé din volumul La lanterne magique; Si seul din volumul A cloche-pied © Fondation Maurice Carême, toate drepturile rezervate Robert Desnos, Le chat qui ne ressemblait à rien din volumul Destinée arbitraire © Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1975 Colette, Le petit chat noir © Anne de Jouvenel Eleanor Farjeon, Cats © The Estate of Eleanor Farjeon Eugène Ionesco, Rhinocéros (fragmente), din volumul Théâtre III © Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1963 Rudolf Kassner, Der Zauberer (fragment) din volumul Der Gott und die Chimäre. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

”Lost Generation”. the Phoenix Bird of Aesthetics Arising from the Refusal of Aesthetics

CCI3 LITERATURE THE NEW POETRY AND THE NEW POETICS OF THE ”LOST GENERATION”. THE PHOENIX BIRD OF AESTHETICS ARISING FROM THE REFUSAL OF AESTHETICS Sorin Ivan, Prof., PhD, ”Titu Maiorescu” University of Bucharest Abstract: The poets of the Albatros magazine are the heart of a generation that aims to revolutionize literature and to create a new poetry. At the origin of this movement there lies an ontologically based aesthetic explanation: the desire of separation from the literary tradition and the aesthetic canons (a polemical and iconoclastic breakup), the need for poetic renewal in a time under the sign of urgency, of change and of desire for rebirth from the ruins of the war. In the young poets’ vision, poetry must descend from the metaphysical heavens of an empty aesthetics into the immediate reality, as an instrument of life, as a way of living. The new poetry is born from the ashes of an outdated aesthetics and from the ashes of time, with a new, messianic meaning, proclaiming the future and the new man. The poets of the Albatros magazine, and others, who write in the literary press of the time, thus create a revolutionary movement in the literary mentality and poetry. Out of the anti-poetic and anti- aesthetic ideology of this movement, a new aesthetic is born, from which the new poetry grows. In this context, Geo Dumitrescu is an iconic poet for the new aesthetics, raised from negation, and for the new poetry. It is interesting to see which are the defining elements of the anti-aesthetic and anti-poetic aesthetics and what the ”new poetry”, promoted by the war generation, means compared to the ”old poetry”. -

Communication Interculturelle Et Littérature

Centrul de Cercetare Comunicare Interculturală şi Literatură, Facultatea de Litere, Universitatea “Dunărea de Jos”, Galaţi COMMUNICATION INTERCULTURELLE ET LITTÉRATURE NR. 1 (28) / 2019 Volum I Coordonatori: Simona Antofi, Nicoleta Ifrim, Oana Cenac Daniel Gălățanu, Elena Botezatu, Iuliana Barna Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Cluj-Napoca 2019 Editor : Centrul de Cercetare Comunicare Interculturală şi Literatură, Facultatea de Litere, Universitatea „Dunărea de Jos”, Galaţi Director: Prof. univ. dr. Doiniţa Milea e-mail: [email protected] Redactor-şef: Prof. univ. dr. Simona Antofi e-mail: [email protected] Secretar de redacţie: Prof. univ. dr. Nicoleta Ifrim e-mail: [email protected] Redactori : Prof. univ. dr. Nicoleta Ifrim, Conf. univ. dr. Oana Cenac e-mail: [email protected],, [email protected] Rezumat în limba engleză / franceză : Prof. univ. dr. Nicoleta Ifrim, Conf. univ. dr. Oana Cenac, Prof. univ. dr. Simona Antofi, Prof. univ. dr. Daniel Gălățanu Administrare site şi redactor web : Prof. univ. dr. Nicoleta Ifrim Corectură: Prof.univ. dr. Nicoleta Ifrim, Conf. univ. dr. Oana Cenac, Prof. Marian Antofi Difuzare: Prof. univ. dr. Nicoleta Ifrim Consiliul consultativ: Academician Eugen Simion, Prof. univ. dr. Silviu Angelescu, Prof. univ. dr. Mircea A. Diaconu Adresa redacţiei: Centrul de Cercetare Comunicare Interculturală şi Literatură, Facultatea de Litere, Universitatea Dunărea de Jos”, Str. Domnească, nr. 111, Galaţi Cod poştal: 800008 Telefon: +40-236-460476 Fax: +40-236-460476 ISSN : 1844-6965 Communication Interculturelle et Littérature Cod CNCSIS 489 / 2008 Abonamentele se fac la sediul redacţiei, Str. Domnească, nr. 111, Galaţi, cod 800008, prin mandat poştal pe numele Simona Antofi. Preţurile la abonamente sunt: 3 luni – 30 lei; 6 luni - 60 lei ; 12 luni – 120 lei. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE VICTOR V. PAMBUCCIAN |ADDRESS, E-MAIL, TELEPHONE | Work: School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences Arizona State University - West campus, P O Box 37100 Phoenix, AZ 85069-7100 | e-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (602)-543-3021 |EMPLOYMENT | Professor of Mathematics, ASU West, Fall 2007 - | Associate Professor of Mathematics, ASU West, Fall 1999 - Spring 2007 | Assistant Professor of Mathematics, ASU West, Spring 1994 - Spring 1999 | Teaching Assistant at the University of Michigan (9/89-5/93), and Lecturer in Mathematics (9/93-12/93) | French and Mathematics teacher at the \National Sports Academy in Lake Placid", Lake Placid, NY (9/88-6/89) |EDUCATION |University of Michigan (9/89 - 8/93) Ph. D. in Mathematics (August 1993) Major Area: Logic, Foundations of Geometry Dissertation Title: The Axiomatics of Euclidean Geometry Thesis Adviser: Prof. Andreas Blass | University of Bucharest, Faculty of Mathematics (1978-1982) Master of Sciences in Mathematics, June 1982 M.S. Thesis Title: The problem of the axiomatic foundation of Euclidean geometry (120pp.) Thesis Adviser: Prof. Kostake Teleman | \Deutsches Lyzeum", Bucharest, Rumania (1974-1978) Baccalaureat (\Abitur") diploma, September 1978 |ACADEMIC AWARDS and SCHOLARSHIPS | 1st; 2nd prizes of the \Gazeta Matematica" (Bucharest, 1975; 1976) | 3rd; 1st; 2nd; 1st; 2nd prizes at the \Bundeswettbewerb Mathematik" (West German Mathematical Competition) (Bonn, 1976; 1977; 1977; 1978; 1978) | Two prizes at the \Prindle, Weber & Schmidt Undergraduate Math. Competition" II -

Ion Creangă Clasic Al Artei Naive

Apare sub egida UniuniiExpres Scriitorilor din România cultural Anul III, nr. 6 (30), iunie 2019 • Apare lunar 24 pagini Aproape de aproape Aproape de aproape în rădăcina asta ceva se străduie să redevină iar noi rămâne să ne întrebăm dacă să trecem cu Homo vederea blândețea lui nimicitoare academicus urmează o rostogolire și poate o zguduită claritate sub vremi care falsifică și uită atunci cu greu mai recunoaștem grația electrică a vechilor bărbați pe care îi văzusem mai demult cum își cărau cămășile coclite pag. 4 prin mlaștina care îi dogorea și se plantau cu brațele în cruce cu un condor pe fiecare umăr Alexandru ZUB bărbații care vroiau să moară și își zdrobeau și oa- sele ca mama mamei lor și ies în ploaie să-mi dezleg frânghia de care sunt legat Gellu Naum Liviu Ioan STOICIU Al. CISTELECAN Nu e de ajuns talentul, trebuie să aibă și... Radu FLORESCU, Dan Bogdan HANU pag. 3 O fată fericită (Raymond Han) Constantin COROIU POESIS pag. 7 pag. 12,13 G. Călinescu și „fapta văzută din viitor” Christian W. SCHENK pag. 5 Florin FAIFER Rainer Maria Rilke - poezie universală pag. 15 Îndrăgostiți într-o lume de minunății Adrian Dinu RACHIERU pag. 5 Constantin DRAM Un histrion mediatic. Adrian Păunescu (I) pag. 18 Catharsis! Theodor CODREANU pag. 6 Gellu DORIAN Numere în labirint (IV) pag. 21 De ce n-au devenit Ipoteștii și Botoșanii... Victor DURNEA pag. 7 Al. CISTELECAN Radu Rosetti pag. 23 O poetă „miss România” (sau invers) Constantin PRICOP pag. 9 Magda URSACHE Direcția critică (XXIV) Proletcult după proletcult - .. -

Gellu Naum in Heterotopia

НАУЧНИ ТРУДОВЕ НА РУСЕНСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ - 2009, том 48, серия 6.3 Gellu Naum in Heterotopia Brînduşa Dragomir Abstract: The paper relates the concept of heterotopia, created by Michel Foucault, with Avant-garde, surrealist poetry, and with Gellu Naum’s poetry in particular. Michel Foucault’s concept provides a means of approaching the avant-garde literature from outside the literary ground, rejected by the Avant-garde writers. Transfered to literature, this concept makes it possible for the Avant-garde to preserve its particular characteristics, opening new, interesting perspectives for the analysis of these obscure texts. Key words: heterotopia, Avant-garde, Surrealism. In an article published in 1984, reproducing the text of a conference in 1967, Of Other Spaces, which was translated in Romanian by Bogdan Ghiu, Michael Foucault – phylosopher, literary analist, historian and sociologist, formulates and proposes the concept of heterotopia. Discussing the obsessions that mark the collective mentality, Michael Foucault affirms that the epoch we live in is an “epoch of space”, just as the nineteenth century belonged to history. “We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed. We are at a moment. I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.” The author underlines the fact that the concept of space does not represent an innovation, but it has a history of its own, and he gives as an example the case of the Middle Ages – period in which space was regarded as “a hierarchic ensemble of places: sacred places and profane plates: protected places and open, exposed places: urban places and rural places (all these concern the real life of men). -

Ion Horea. Biographical Exploration

SECTION: LITERATURE LDMD I ION HOREA. BIOGRAPHICAL EXPLORATION Anamaria ŞTEFAN (PAPUC), PhD Candidate, ”Petru Maior” University of Târgu- Mureş Abstract: Although the biography of a writer should not be the tool for evaluation of his work, it has the task of enriching some directions of interpretation and also of the close as the writer to the reader. Biography is an important dimension because sometimes improves the comprehension of the text. This paper treats the Transylvanian poet biography Ion Horea, as evidenced lesser known aspects of his life and details about the circumstances of writing and publishing his works. Keywords: biography, Ion Horea, Transylvanian poet, new traditionalism Cu toate că biografia unui scriitor nu trebuie să constituie instrumentul de evaluare a operei acestuia, ea are sarcina de a îmbogăţi unele direcţii de interpretare şi totodată, de a-l apropia cât mai mult pe scriitor de cititor. Lucrarea de faţă se ocupă de biografia poetului ardelean Ion Horea, fiind evidenţiate aspecte mai puţin cunoscute ale vieţii sale, precum şi detalii legate de circumstanţele scrierii şi publicării operelor sale. Cunoaşterea vieţii autorului, precum şi a contextului socio-politic în care acesta şi-a desfăşurat activitatea – ca secretar al Uniunii Scriitorilor, ca redactor la „România literară”, este esenţială pentru înţelegerea anumitor aspecte ale operei sale. Nu sunt neglijate nici perioada copilăriei şi cea a adolescenţei, foarte importante pentru scriitorul de mai târziu, chiar determinante. Situat în centrul podişului Transilvaniei, la o distanţă de 21 de kilometri de Târgu- Mureş, satul unde au trăit generaţiile neamului Horgoş – de unde provine Ion Horea – poartă azi denumirea de Petea, în trecut fiind denumit Petea de Câmpie, aflându-se în subordinea comunei Band, judeţul Mureş. -

Dialectica Imaginarului În Opera Lui Gellu Naum

Dialectica imaginarului în opera lui Gellu Naum Titlul eseului nostru critic, Dialectica imaginarului în opera lui Gellu Naum, sintetizează, întro formulă tehnică, intenţia de a investiga textul poetic al unui mare scriitor român suprarealist din perspectiva deschiderilor semantice proprii conceptului de ,,imaginar”. De aceea, incursiunea în opera poetului a presupus, mai întâi, actualizarea reflexelor dominante ale acestui termen, marcate de cercetătorul Jean Burgos, conjugate cu cele ale lui Gilbert Durand şi ale lui Gaston Bachelard. Acceptarea imaginarului nu ca o structură de imagini, ci ca o structurare, o devenire a acestora, niciodată finită şi definită, reactualizată prin actul lecturii, al receptării operei, nea creat spaţiul unei ample cuprinderi a operei lui Gellu Naum, în sensul configurării specificităţii acesteia. Raportarea imaginarului la estetica suprarealismului, curent literar de avangardă din secolul trecut, ale cărui ecouri surprind şi astăzi, a relevat ideea că, în ansamblul său, acest concept suportă abordarea ca un posibil reflex al doctrinei suprarealiste, prin caracterul său deschis, discontinuu, supus intuiţiei şi viziunii creatorului său. Având în vedere aceste delimitări, am învestit structura ,,dialectica imaginarului” cu valenţele unei metode hermeneutice, opţiune ce nea orientat structurarea demersului nostru analitic în cinci părţi, structurare impusă şi de vastitatea şi plurisemantismul operei lui Gellu Naum. Prima secvenţă a lucrării, Profilul biobibliografic adnotat (cu opinii ale autorului şi ale -

Geo Dumitrescu. from the Apprenticeship to Mentorship

I.Boldea, C. Sigmirean, D.-M.Buda THE CHALLENGES OF COMMUNICATION. Contexts and Strategies in the World of Globalism GEO DUMITRESCU. FROM THE APPRENTICESHIP TO MENTORSHIP Viorica-Macrina Lazăr PhD, ”George Sbârcea” Municipal Library Toplița Abstract: The study shows Geo Dumitrescu`s evolution in his literay and journalistic as a writer, from the first steps to the last from the montorship point of wiew. We also present the direction which he embraced in crucial moments, when the comunism took the power in Romania, above all his change of perspective, in the his last period of creation. Our article reveal his important role in the the renewal of the poetry, observing his marks for the future generation. As a wholeness we atach in this point a wiew upon his work at the Albatros Literary Magazine and upon the important step that he made with The liberty to shoot shotgun. We present to his oscillations, his fights to return to the values that he had and wich are visible in his lyrics, too. In the final part we reveal the most important aspects and significances of the lyrics he wrote in the last period of life. Keywords: Geo Dumitrescu inconformism mentor modern poetry Rămas în memoria literaturii ca mentor al grupului de la revista „Albatrosŗ, Geo Dumitrescu este acel poet al generației „pierduteŗ, care a concentrat suferințele și întrebările acesteia, integrând-o într-o viziune literară catalizatoare antipoetică şi antiutopică. Înrădăcinat într-o creație fundamental înnoită, acesta a dat naștere, pe nesimțite, unor noi perspective în poezia românească. Poezia sa iconoclastă făcea apel la rațiune și a reprezentat un izvor literar pentru viitorii poeți, în special prin „fanfaronada cu substrat manifestŗ pe care o reprezenta în poeme eul liric. -

EURESIS 1-200 C1 12/2/10 8:36 AM Page 1

EURESIS 1-200 c1 12/2/10 8:36 AM Page 1 Le postmodernisme roumain, alors et maintenant Romanian Postmodernism, then and now EURESIS 1-200 c1 12/2/10 4:45 PM Page 2 Sur la couverture: Dessin de Vasile Kazar Illustrated by: Vasile Kazar EURESIS 1-200 c1 12/2/10 8:36 AM Page 3 EURESIS no. 1–4/2009 cahiers roumanins d’études littéraires et culturelles Romanian Journal of Literary and Cultural Studies Le postmodernisme roumain, alors et maintenant Romanian Postmodernism, then and now TABLE DE MATIÈRES Le postmodernisme alors/ postmodernism then… MIRCEA MARTIN – D’un postmodernisme sans rivages et d’un postmodernisme sans postmodernité . 11 VIRGIL NEMOIANU – Notes sur l’état de postmodernité. 23 IOANA. EM. PETRESCU – Modernism/Postmodernism: A Hypothetical Model . 26 DAN GRIGORESCU – Modernisme/postmodernisme: un processus de continuité?. 33 ANGÈLE KREMER°MARIETTI – La postmodernité: achèvement ou commencement? . 40 LINDA HUTCHEON – Postmodernism Goes to the Opera . 54 AMELIA PAVEL – Le postmodernisme et l’historiographie de l’art . 67 VALENTINA SANDU°DEDIU – Points de vue sur le postmodernisme musical . 72 *** ALEXANDRU MUØINA – Le postmodernisme aux portes de l’Orient. 85 ION BOGDAN LEFTER – La reconstruction du moi de l’auteur . 99 GHEORGHE CRÆCIUN – Entre le modernisme et le postmodernisme. 103 LIVIU PAPADIMA – Postmodernisme littéraire et modèles culturels. 117 ION MANOLESCU – La prose postmoderniste et le textualisme médiatique . 125 ANA°MARIA TUPAN– The Rhetoric of Displacement . 131 RODICA ZAFIU – Postmodernisme et langage. 136 AUGUSTIN IOAN – Le postmodernisme dans l’architecture: ni sublime, ni complètement absent . 145 MAGDA CÂRNECI – The Debate Around Postmodernism in Romania in the 1980s . -

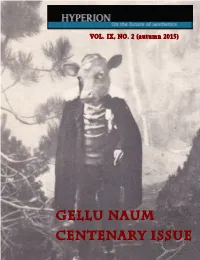

Gellu Naum Centenary Issue

VOL. IX, NO. 2 (autumn 2015) GELLU NAUM CENTENARY ISSUE !!! MAST HEAD Publisher: Contra Mundum Press Location: New York, London, Paris Editors: Rainer J. Hanshe, Erika Mihálycsa PDF Design: Giuseppe Bertolini Logo Design: Liliana Orbach Advertising & Donations: Giovanni Piacenza (To contact Mr. Piacenza: [email protected]) Letters to the editors are welcome and should be e-mailed to: [email protected] Hyperion is published biannually by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. P.O. Box 1326, New York, NY 10276, U.S.A. W: http://contramundum.net For advertising inquiries, e-mail Giovanni Piacenza: [email protected] Contents © 2015 Contra Mundum Press & each respective author unless otherwise noted. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Contra Mundum Press. Republication is not permitted within six months of original publication. After two years, all rights revert to each respective author. If any work originally published by Contra Mundum Press is republished in any format, acknowledgement must be noted as following and include, in legible font (no less than 10 pt.), a direct link to our site: “Author, work title, Hyperion: On the Future of Aesthetics, Vol. #, No. # (YEAR) page #s. Originally published by Hyperion. Reproduced with permission of Contra Mundum Press.” Vol. IX, No. 2 — GELLU NAUM CENTENARY ISSUE Curated by Guest Editor VALERY OISTEANU 0 Valery Oisteanu, Gellu Naum: Surreal-Shaman of Romania 16 Petre Răileanu, Poésie & alchimie 25 Petre Răileanu, Poetry & Alchemy 36 Sebastian Reichmann, Ici & Maintenant (de l’Autre Côté)..