Highlights from Sammlung Klein 08.01 – 30.01.2021 at Michael Reid Berlin Highlights from Sammlung Klein 08.01 – 30.01.2021 at Michael Reid Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

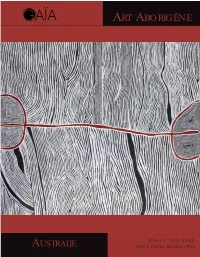

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 Mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie

ART ABORIGÈNE, AUSTRALIE — Samedi 7 mars 2020 — Paris, Salle VV Quartier Drouot Art Aborigène, Australie Samedi 7 mars 2020 Paris — Salle VV, Quartier Drouot 3, rue Rossini 75009 Paris — 16h30 — Expositions Publiques Vendredi 6 mars de 10h30 à 18h30 Samedi 7 mars de 10h30 à 15h00 — Intégralité des lots sur millon.com Département Experts Index Art Aborigène, Australie Catalogue ................................................................................. p. 4 Biographies ............................................................................. p. 56 Ordres d’achats ...................................................................... p. 64 Conditions de ventes ............................................................... p. 65 Liste des artistes Anonyme .................. n° 36, 95, 96, Nampitjinpa, Yuyuya .............. n° 89 Riley, Geraldine ..................n° 16, 24 .....................97, 98, 112, 114, 115, 116 Namundja, Bob .....................n° 117 Rontji, Glenice ...................... n° 136 Atjarral, Jacky ..........n° 101, 102, 104 Namundja, Glenn ........... n° 118, 127 Sandy, William ....n° 133, 141, 144, 147 Babui, Rosette ..................... n° 110 Nangala, Josephine Mc Donald ....... Sams, Dorothy ....................... n° 50 Badari, Graham ................... n° 126 ......................................n° 140, 142 Scobie, Margaret .................... n° 32 Bagot, Kathy .......................... n° 11 Tjakamarra, Dennis Nelson .... n° 132 Directrice Art Aborigène Baker, Maringka ................... -

STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O’Hara, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE by MArguerite o’hArA, jonAthAn jones And amandA PeAcock http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins Front cover: (top) Detail From GinGer riley munDuwalawala, Ngak Ngak aNd the RuiNed City, 1998, synthetic polyer paint on canvas, 193 x 249.3cm, art Gallery oF new south wales. © GinGer riley munDuwalawala, courtesy alcaston Gallery; (Bottom) Kintore ranGe, 2009, warwicK thornton; (inset) hetti perKins, 2010, susie haGon this paGe: (top) Detail From naata nunGurrayi, uNtitled, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 2 122 x 151 cm, mollie GowinG acquisition FunD For contemporary aBoriGinal art 2000, art Gallery oF new south wales. © naata nunGurrayi, aBoriGinal artists aGency ltD; (centre) nGutjul, 2009, hiBiscus Films; (Bottom) ivy pareroultja, rrutjumpa (mt sonDer), 2009, hiBiscus Films Introduction GulumBu yunupinGu, yirrKala, 2009, hiBiscus Films DVD anD WEbsitE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

Art Aborigène, Australie Samedi 10 Décembre 2016 À 16H30

Art Aborigène, Australie Samedi 10 décembre 2016 à 16h30 Expositions publiques Vendredi 9 décembre 2016 de 10h30 à 18h30 Samedi 10 décembre 2016 de 10h30 à 15h00 Expert Marc Yvonnou Tel : + 33 (0)6 50 99 30 31 Responsable de la vente Nathalie Mangeot, Commissaire-Priseur [email protected] Tel : +33 (0)1 48 00 94 24 / Port : +33 (0)6 34 05 27 59 En partenariat avec Collection Anne de Wall* et à divers collectionneurs australiens, belges, et français La peinture aborigène n’est pas une peinture de chevalet. Les toiles sont peintes à même le sol. L’orientation des peintures est le plus souvent un choix arbitraire : c’est à l’acquéreur de choisir le sens de la peinture. Des biographies se trouvent en fin de catalogue. Des certificats d’authenticité seront remis à l’acquéreur sur demande. * co-fondatrice du AAMU (Utrecht, Hollande) 2 3 - - Jacky Giles Tjapaltjarri (c. 1940 - 2010) Eileen Napaltjarri (c. 1956 - ) Sans titre, 1998 Sans titre, 1999 Acrylique sur toile - 45 x 40 cm Acrylique sur toile - 60 x 30 cm Groupe Ngaanyatjarra - Patjarr - Désert Occidental Groupe Pintupi - Désert Occidental - Kintore 400 / 500 € 1 300 / 400 € - Anonyme Peintre de la communauté d'Utopia Acrylique sur toile - 73 x 50,5 cm Groupe Anmatyerre - Utopia - Désert Central 300/400 € 4 5 6 - - - Billy Ward Tjupurrula (1955 - 2001) Toby Jangala (c. 1945 - ) Katie Kemarre (c. 1943 - ) Sans titre, 1998 Yank-Irri, 1996 Awelye; Ceremonial Body Paint Design Acrylique sur toile - 60 x 30 cm Acrylique sur toile - 87 x 57 cm Acrylique sur toile Groupe Pintupi - Désert Occidental Groupe Warlpiri - Communauté de Lajamanu - Territoire du Nord 45 x 60 cm Cette toile se réfère au Rêve d’Emeu. -

Origines•210708-88P-2 30/06/08 16:07 Page 1

Origines•210708-88p-2 30/06/08 16:07 Page 1 Origines•210708-88p-2 30/06/08 16:07 Page 2 Origines•210708-88p-2 30/06/08 16:07 Page 1 ART AFRICAIN, OCÉANIEN, L’AMÉRIQUE PRÉCOLOMBIENNE, PEINTURES ABORIGÈNES D’AUSTRALIE ET ART ANIMISTE DE L’HIMALAYA VENTE LE LUNDI 21 JUILLET 2008 À 17H00 DANS LES SALONS DE L’HÔTEL MARTINEZ 73, Boulevard de la Croisette - 06400 Cannes BESCH CANNES AUCTION Maître Jean-Pierre Besch, commissaire-priseur habilité SVV n° 2002-034 45, Boulevard de la Croisette, 06400 Cannes Tel : 33 (0) 4 93 99 33 49 – 33 (0) 4 93 99 22 60 Fax : 33 (0) 4 93 99 30 03 [email protected] www.cannesauction.com CABINET D’EXPERTISE ORIGINE Serge Reynes, Expert Assisté de Marc Yvonnou, pour l’Art aborigène. 166, Rue Etienne Marcel 93100 Montreuil Tel : 33 (0)1 48 57 91 46 Fax : 33 (0)1 48 57 68 18 www.serge-reynes.org GALERIE EBURNE Joël Bernard, Expert 30, Rue des Tournelles 75004 Paris EXPOSITION CHEZ L’EXPERT Du mardi 1er au vendredi 11 juillet 2008 (sur rendez-vous) EXPOSITION À L’HÔTEL MARTINEZ Vendredi 18 juillet de 17H à 20H Samedi 19 et dimanche 20 juillet de 10H à 19H Lundi 21 juillet de 10H à 12H30 Origines•210708-88p-2 30/06/08 16:08 Page 2 ART DES AMÉRIQUES PRÉOLOMBIENNES 2 3 4 1 VASE ÉTRIER. La panse est modelée de deux têtes de 3 VASE ÉTRIER. La panse ovoïde, à sommet discoïdal, est chevreuil. Terre cuite avec engobe brun. -

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2Pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Tional in Fi Le Only - Over Art Fi Le

Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia tional in fi le only - over art fi le 5 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 6 7 Bonhams The Laverty Collection 1 2 Bonhams Sunday 24 March, 2013 at 2pm Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, Australia Bonhams Viewing Specialist Enquiries Viewing & Sale 76 Paddington Street London Mark Fraser, Chairman Day Enquiries Paddington NSW 2021 Bonhams +61 (0) 430 098 802 mob +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 +61 (0) 2 8412 2222 101 New Bond Street [email protected] +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax +61 (0) 2 9475 4110 fax Thursday 14 February 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] Friday 15 February 9am to 4.30pm Greer Adams, Specialist in Press Enquiries www.bonhams.com/sydney Monday 18 February 9am to 4.30pm Charge, Aboriginal Art Gabriella Coslovich Tuesday 19 February 9am to 4.30pm +61 (0) 414 873 597 mob +61 (0) 425 838 283 Sale Number 21162 [email protected] New York Online bidding will be available Catalogue cost $45 Bonhams Francesca Cavazzini, Specialist for the auction. For futher 580 Madison Avenue in Charge, Aboriginal Art information please visit: Postage Saturday 2 March 12pm to 5pm +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob www.bonhams.com Australia: $16 Sunday 3 March 12pm to 5pm [email protected] New Zealand: $43 Monday 4 March 10am to 5pm All bidders should make Asia/Middle East/USA: $53 Tuesday 5 March 10am to 5pm Tim Klingender, themselves aware of the Rest of World: $78 Wednesday 6 March 10am to 5pm Senior Consultant important information on the +61 (0) 413 202 434 mob following pages relating Illustrations Melbourne [email protected] to bidding, payment, collection fortyfive downstairs Front cover: Lot 21 (detail) and storage of any purchases. -

Remembering Forward: Paintings of Australian Aborigines Since 1960 240 Pages, Hardback, 310 X 240 Mm, 150 Illustrations

Paul Holberton publishing THIRD FLOOR 89 BOROUGH HIGH STREET LONDON SE1 1NL TEL 020 7407 0809 FAX 020 7407 4615 [email protected] WWW.PAUL-HOLBERTON.NET Remembering Forward Paintings of Australian Aborigines since 1960 Edited by Kasper König, Emily Evans and Falk Wolf The publication Remembering Forward accompanies the exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, 20 November 2010 to 20 March 2011, which presents the work of nine of the most prominent Australian Aboriginal artists of recent years: Paddy Bedford, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Queenie McKenzie, Dorothy Napangardi, Rover Thomas, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri and Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula. This is the first time that an art museum outside Australasia has devoted an exhibition to the works of these artists. The title Remembering Forward refers to the tension among tradition, present and future that determines the demands made of artists. On the one hand, they usually take as their subject the so-called ‘Dreamtime’ of prehistory from which myths of the earth’s and humankind’s creation have been handed down. In that regard they are deeply traditional. On the other, these artists have radically changed their medium and method of art-making over the last forty years. Inherited practices of sand- and body-painting have been transformed such that the paintings are executed in acrylic on canvas or other portable media. These changes afforded the artists entry to the global art market. Thus they have adjusted to address an outside public and keep the images free of those parts of the Dreamings that, in their own culture, are reserved for the initiated. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

The Dream of Aboriginal

The Dream of • Aboriginal Art The author reflects on the vil1lal richness and symbolic complexity oj an artjorm that has come to occupy a significant place in the his/my oj modernism. BY RICHARD KALINA " W IO'S that bugger who Ila ints like me?" asked Ho\'cr Thomas, olle of AustralL.'1's greatest Aboriginal IxllnlCrs, when, in 1990, he first encountered Mark Rothko's 1957 '20 at the National Gal lery of AUSlI'aIia. The question is a re.'ealing inversion of the art is diminished or patronized; \iewed as a bastardized modernism, a often Eurocenuic view of marginally interesting branch of folk art. or simply a subject for cultural Aborigi nal art. Thomas, an anthropology. In fact, the week before I visited ~ Dreaming Their Way,ft artist from the \\estem Des a magnificent exhibition of art by 33 Aboriginal women, at Dartmouth en, 1)''I.inted seemingly simille, College's Hood Museum in New lIam pshire {it originated at the National often blocky forms using a Museum of Women in the Art.'! in Washington, D.C.), I mentioned IllY inter range of na tural ocher pig est in Aboriginal art, and this show in particular, to a vcry senior American menls. I.ike Rathko's, his work crilic. He dismissed it all out of hand. 1 don't remember the exact words, is spare yet ~boIic and emo but "third·rale lyrical abstractionft .....ou ld certa.inly com'C}' hisjudgmenL tionally resonant, and though he lived in a \'el'l' remote area he best-knO\\'T1 fonn of modem Aboriginal art, characterized by all and came to art lale in his life, T O\'ef dotting and associated with desert communities. -

Art Aborigène

ART ABORIGÈNE LUNDI 1ER JUIN 2009 AUSTRALIE Vente à l’Atelier Richelieu - Paris ART ABORIGÈNE Atelier Richelieu - 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Vente le lundi 1er juin 2009 à 14h00 Commissaire-Priseur : Nathalie Mangeot GAÏA S.A.S. Maison de ventes aux enchères publiques 43, rue de Trévise - 75009 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 00 - Fax : 33 (0)1 44 83 85 01 E-mail : [email protected] - www.gaiaauction.com Exposition publique à l’Atelier Richelieu le samedi 30 mai de 14 h à 19 h le dimanche 31 mai de 10 h à 19 h et le lundi 1er juin de 10 h à 12 h 60, rue de Richelieu - 75002 Paris Maison de ventes aux enchères Tous les lots sont visibles sur le site www.gaiaauction.com Expert : Marc Yvonnou 06 50 99 30 31 I GAÏAI 1er juin 2009 - 14hI 1 INDEX ABRÉVIATIONS utilisées pour les principaux musées australiens, océaniens, européens et américains : ANONYME 1, 2, 3 - AA&CC : Araluen Art & Cultural Centre (Alice Springs) BRITTEN, JACK 40 - AAM : Aboriginal Art Museum, (Utrecht, Pays Bas) CANN, CHURCHILL 39 - ACG : Auckland City art Gallery (Nouvelle Zélande) JAWALYI, HENRY WAMBINI 37, 41, 42 - AIATSIS : Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres JOOLAMA, PADDY CARLTON 46 Strait Islander Studies (Canberra) JOONGOORRA, HECTOR JANDANY 38 - AGNSW : Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney) JOONGOORRA, BILLY THOMAS 67 - AGSA : Art Gallery of South Australia (Canberra) KAREDADA, LILY 43 - AGWA : Art Gallery of Western Australia (Perth) KEMARRE, ABIE LOY 15 - BM : British Museum (Londres) LYNCH, J. 4 - CCG : Campbelltown City art Gallery, (Adelaïde) -

THE DEALER IS the DEVIL at News Aboriginal Art Directory. View Information About the DEALER IS the DEVIL

2014 » 02 » THE DEALER IS THE DEVIL Follow 4,786 followers The eye-catching cover for Adrian Newstead's book - the young dealer with Abie Jangala in Lajamanu Posted by Jeremy Eccles | 13.02.14 Author: Jeremy Eccles News source: Review Adrian Newstead is probably uniquely qualified to write a history of that contentious business, the market for Australian Aboriginal art. He may once have planned to be an agricultural scientist, but then he mutated into a craft shop owner, Aboriginal art and craft dealer, art auctioneer, writer, marketer, promoter and finally Indigenous art politician – his views sought frequently by the media. He's been around the scene since 1981 and says he held his first Tiwi craft exhibition at the gloriously named Coo-ee Emporium in 1982. He's met and argued with most of the players since then, having particularly strong relations with the Tiwi Islands, Lajamanu and one of the few inspiring Southern Aboriginal leaders, Guboo Ted Thomas from the Yuin lands south of Sydney. His heart is in the right place. And now he's found time over the past 7 years to write a 500 page tome with an alluring cover that introduces the writer as a young Indiana Jones blasting his way through deserts and forests to reach the Holy Grail of Indigenous culture as Warlpiri master Abie Jangala illuminates a canvas/story with his eloquent finger – just as the increasingly mythical Geoffrey Bardon (much to my surprise) is quoted as revealing, “Aboriginal art is derived more from touch than sight”, he's quoted as saying, “coming as it does from fingers making marks in the sand”. -

AUSTRALIA : CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUS ART from the CENTRAL DESERT Kathleen PETYARRE, “My Country - Bush Seeds” Acrylic on Canvas, 137 X 137 Cm, 2010

AUSTRALIA : CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUS ART FROM THE CENTRAL DESERT Kathleen PETYARRE, “My Country - Bush Seeds” acrylic on canvas, 137 x 137 cm, 2010 The paintings of Australian Indigenous artist Kathleen Petyarre have been compared internationally to those of the minimalist modern artists Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin, not so much for their formal structure: but for what underlies beneath, partially hidden from the observers view. In actuality, Kathelen Petyarre’s paintings are mental territorial maps which portray her country and the narrative associated with her inherited Dreaming stories. Her celebrated work, “My Country - Bush Seeds”, presents a seasonal snapshot within: a close-up of a geographical location spiritually important to the artist. The prominent parallel lines represent a group of red sand-hills – a sacred site - that rise majestically from the desert floor. Abie Loy KEMARRE, “Bush Hen Dreaming” acrylic on canvas, 91 x 152 cm, 2009 Australian Indigenous artist Abie Loy Kemarre began painting in 1994 under the formidable guidance of her famous grandmother, Kathleen Petyarre, who imparted the methodology for creating the depth-of-field of tiny shimmering dots in her highly delicate Bush Hen Dreaming painting that represents her Ancestral country. The Bush Hen travels through this country looking for bush seeds which are scattered over the land, represented by the fine dotting. The centre of this painting shows body designs used in traditionel women’s sacred ceremonies. These ceremonies are performed with songs and dance cycles telling stories of the Bush Hen Dreaming. Ngoia Pollard NAPALTJARRI, “Swamp around Nyruppi” acrylic on canvas, 180 x 180 cm, 2006 Western Desert artist Ngoia Pollard frequently paints particular Dreamings, or stories, for which she has personal responsibility or rights.