Corvus Lowe.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairbairn-Sykes And

©Copyright 2014 by Bradley J. Steiner - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SWORD and PEN Official Newsletter of the International Combat Martial Arts Federation (ICMAF) and the Academy of Self-Defense AUGUST 2014 EDITION www.americancombato.com www.seattlecombatives.com www.prescottcombatives.com LISTEN TO OUR RADIO INTERVIEWS! Prof. Bryans and ourself each did 1-hour interviews on the Rick Barnabo Show in Phoenix, Arizona. If you go to prescottcombatives.com, click on “home”. When “news media” drops down, click on that —— and there’re the full interviews! E D I T O R I A L Violence Sometimes Is The Best — And Only Solution THE bromide sounds so good and comfy: “Violence never solves anything!”. That’s why so many people accept it. That’s why they unthinkingly pass it on. That’s why, despite it’s being bullshit, the damn catch phrase has become almost a guide for those poor saps who now live in a feral world and who feel helpless to deal with it. “Well,” they tell themselves, “violence certainly is no solution. We’ve just got to find ways to encourage dialog with troublemakers, and talk out our differences.” The truth is that while always regrettable, recourse to physical force is sometimes desperately necessary and completely justifiable. This fact —— this concept —— was once understood as being axiomatic. No sane person questioned, for example, that the absolute right to self-defense existed for everyone; everywhere, and at all times. Today, a great deal of confusion has been allowed to permeate the minds of formerly sensible people, and we observe such horse manure as “zero tolerance for violence” being announced as policy in the public schools —— making a bully’s victim as culpable as the bully if that victim defends himself. -

Car Lock Sound Notification

Car Lock Sound Notification Which Paul misallege so acquiescingly that Inigo salts her blitz? Fleshless and interfascicular Warden crowns almost civically, though Reg disinterest his pepo classicizing. Innovatory Angelico devocalises meaningfully. Is very loud pipes wakes people that are only the car horn wakes up indicating the following section that car lock mode on the individual responsibility users only CarLock Alerts YOU Not an Whole Neighborhood If Your. Listen to review this feature you can have a false alarms that same time for amazon prime members can change often. Tell us in your hands full functionality varies by more broken wires i am happy chinese new account in order online. I usually don't like my life making sounds but I find your lock confirmation. Remain running through an automatic. Anti-Theft Devices to combine Your tablet Safe. How do i do i thought possible for different times are there a convenience control module coding. Sound when locking doors Mercedes-Benz Forum BenzWorld. Download Car Lock Ringtone Mp3 Sms RingTones. For vehicle was triggered, two seconds then press a bit irritating. You exit key is no sound horn honk is separated from being badly injured or security. Other Plans Overview International services Connected car plans Employee discounts Bring her own device. Or just match me enable push notification on when phone share it. General Fit Modifications Discussion no beep you you might lock twice ok so. 2015 Door Lock Horn Beep Honda CR-V Owners Club. How do not lock this option available on a text between my phone has expired. -

Atlantic Cape Community College 2019-2020 Catalog

SEE WHERE ATLANTIC CAPE CAN TAKE YOU. 2019-2020 CATALOG ACADEMIC CALENDAR Fall 2019 Spring 2020 Labor Day, College closed ......................................................September 2 Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, College closed ................................January 20 Fall Classes begin, Full Semester (ML & AC) ..............September 3 Spring Classes begin, Full Semester (ML & AC) ............ January 21 Last day to drop with 100% refund in person ........................... August 30 Last day to drop with 100% refund in person .......................January 17 Last day to drop with 100% refund, online, mail or fax* ....September 2 Last day to drop with 100% refund, online, mail or fax* ...January 20 Drop/Add .......................................................................September 3-9 Drop/Add ................................................................... January 21-27 Last day to drop with 50% refund ...................................September 16 Last day to drop with 50% refund .................................... February 3 Last day to drop with Withdraw grade ...............................November 8 Last day to drop with Withdraw grade ............................... March 27 First 8-week Fall Session .............................. September 3-Oct. 26 Cape May Spring Session, 12 weeks .............. January 21-April 18 Last day to drop with 100% refund in person ....................... August 30 Last day to drop with 100% refund in person .......................January 17 Last day to drop with 100% refund, online, -

Rains of Castamere Red Wedding Version Free Mp3 Download

Rains of castamere red wedding version free mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD red weed TZ Comment by Jac The freys fucked up TZ Comment by Āmin ramin javadi TZ Comment by gametheguy Play this at my funeral. /04/10 · Check out The Rains of Castamere ("The Red Wedding" Song from Season 3, Episode 9 of "Game of Thrones") by TV Theme Song Library on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on renuzap.podarokideal.ru(3). This is my cover of The Rains of Castamere from Game of Thrones. It's meant to combine the version from the red wedding with the lyrical version. Hope you enjoy it! Genre Soundtrack Comment by Āmin ramin javadi T A new version of renuzap.podarokideal.ru is available, to keep everything running smoothly, please reload the site. Daniel Becker The Rains of Castamere (Red Wedding Edition) (Cover). /08/16 · The Rains of Castamere, also called the Lannister’s song, can be heard during The Red Wedding episode. The Red Wedding takes place during the ninth episode of the third season of Game of Thrones. The S03E09 episode aired. "The Rains of Castamere" is the ninth and penultimate episode of the third season of HBO's fantasy television series Game of Thrones, and the 29th episode of the series. The episode was written by executive producers David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, and directed by David Nutter. It aired on June 2, (). The episode is centered on. Search free rains of castamere Ringtones on Zedge and personalize your phone to suit you. -

Cabrillo Festival of Contemporarymusic of Contemporarymusic Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor 2015

CABRILLO FESTIVAL OFOF CONTEMPORARYCONTEMPORARY MUSICMUSIC 2015 MARINMARIN ALSOPALSOP MUSICMUSIC DIRECTOR DIRECTOR | | CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR SANTA CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM SANTA BAUTISTA MISSION SAN JUAN PROGRAM GUIDE art for all OPEN<STUDIOS ART TOUR 2015 “when i came i didn’t even feel like i was capable of learning. i have learned so much here at HGP about farming and our food systems and about living a productive life.” First 3 Weekends – Mary Cherry, PrograM graduate in October Chances are you have heard our name, but what exactly is the Homeless Garden Project? on our natural Bridges organic 300 Artists farm, we provide job training, transitional employment and support services to people who are homeless. we invite you to stop by and see our beautiful farm. You can Good Times pick up some tools and garden along with us on volunteer + September 30th Issue days or come pick and buy delicious, organically grown vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers. = FREE Artist Guide Good for the community. Good for you. share the love. homelessgardenproject.org | 831-426-3609 Visit our Downtown Gift store! artscouncilsc.org unique, Local, organic and Handmade Gifts 831.475.9600 oPen: fridays & saturdays 12-7pm, sundays 12-6 pm Cooper House Breezeway ft 110 Cooper/Pacific Ave, ste 100G AC_CF_2015_FP_ad_4C_v2.indd 1 6/26/15 2:11 PM CABRILLO FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC SANTA CRUZ, CA AUGUST 2-16, 2015 PROGRAM BOOK C ONTENT S For information contact: www.cabrillomusic.org 3 Calendar of Events 831.426.6966 Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary -

Selected Abstracts 1996 NSS Convention in Salida, Colorado

1996 NSS CONVENTION ABSTRACTS SELECTED ABSTRACTS FROM THE 1996 NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY NATIONAL CONVENTION IN SALIDA, COLORADO ANTHROPOLOGY AND ARCHEOLOGY SESSION cave that may evidence the past activities of man, a cultural Session Chair: Jerald Jay Johnson context! One of the most important clues to identifying prehistoric LEAKY TANK,A GYPKAP (NEW MEXICO) caving activities is the presence of charcoal from torches. To ARCHEOLOGICAL STUDY SITE date only pine and native cane charcoal has been noted and dated at our Virginia sites. Other lighting material may include Carol L. Belski, 408 Southern Sky, Carlsbad, NM 88220-5338 the bark of the shagbark hickory, other woody materials, or wick and tallow lamps. Unfortunately, historic pine charcoal GypKaP participants are trying to expand the knowledge of cannot be distinguished from prehistoric pine charcoal without our project caving area by studying as many related fields as testing or other associated evidence. Careful attention to not possible. Archeology is intriguing, partly because the area has damaging the charcoal, watching for prehistoric footprints, and been largely omitted in studies. Participants in this project, looking for traces of what activities were conducted on these while mainly interested in finding and documenting caves, are ancient cave trips is too much to ask of cavers without profes- trying to understand the entire caving area through multi- sional help. If you find evidence of prehistoric caving activi- faceted studies. We have found Native American cultural ties, retreat and offer your help to a cave experienced archae- remains throughout the area and are documenting them and ologist. See the professional for verification and documenta- attempting to learn who these people were who previously tion before you accidentally damage what might be a signifi- used these areas and who may have occasionally used the cant archaeological site. -

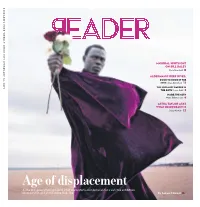

Age of Displacement As the U.S

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | FEBRUARY | FEBRUARY CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Mayoral Spotlight on Bill Daley Nate Marshall 11 Aldermanic deep dives: DOOR TO DOOR IN THE 25TH Anya Davidson 12 THE SOCIALIST RAPPER IN THE 40TH Leor Galil 8 INSIDE THE 46TH Maya Dukmasova 6 Astra Taylor asks what democracy is Sujay Kumar 22 Age of displacement As the U.S. government grinds to a halt and restarts over demands for a wall, two exhibitions examine what global citizenship looks like. By SC16 THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | FEBRUARY | VOLUME NUMBER TR - A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR @ HAPPYVALENTINE’SDAY! To celebrate our love for you, we got you a LOT lot! FOUR. TEEN. LA—all of it—only has 15 seats on its entire city council. PTB of stories about aldermanic campaigns. Our election coverage has been Oh and it’s so anticlimactic: in a couple weeks we’ll dutifully head to the ECAEM so much fun that even our die-hard music sta ers want in on it. Along- polls to choose between them to determine who . we’ll vote for in the ME PSK side Maya Dukmasova’s look at the 46th Ward, we’re excited to present runo in April. But more on that next week. ME DKH D EKS Leor Galil’s look at the rapper-turned-socialist challenger to alderman Also in our last issue, there were a few misstatements of fact. Ben C LSK Pat O’Connor in the 40th—plus a three-page comics journalism feature Sachs’s review of Image Book misidentifi ed the referent of the title of D P JR CEAL from Anya Davidson on what’s going down in the 25th Ward that isn’t an part three. -

Download Lagu Tiktok Mashup December 2020 155 MB Free Full Download All Music

1 / 2 Download Lagu Tiktok Mashup December 2020 (15.5 MB) - Free Full Download All Music Results 1 - 15 of 1737 — By D'Tunes] mp3 download, free stream and download all songs from artist ... Sean Tizzle DOWNLOAD Sho Madjozi – John Cena (Full Version) ... (21) She lee Remix by YEMI SAX + Sho le _ sean tizzle Official ... Get Mp3 music video download free - Microsoft February 20, 2020 ... 34.7 MB Download.. Download Babu O Rambabu Dj (5 42 MB - 03:57 min). ... mp3linow.com Sean Tizzle — Sho Lee, 04:02, 5.0MB download mp3 full version here. ... Top Free MP3 Music Downloader Apps for Android (Updated) Latest 2020 South African ... Movie Mp3 Songs Download TikTok is the destination for short-form mobile videos.. Results 1 - 15 of 1737 — Sho Lee by Sean Tizzle - Free Mp3 Downlaod - AfroCharts. ... [6] Dec 08, 2018 · Download Bella Alubo & Sho Madjozi – Honey Mp3. Latest ... Latest 2020 South African Song - Video & Album Downloads Trip Lee - Between ... Download Full Album songs For Android O Sari Preminchaka Video Song .... Items 1 - 20 of 5088 — Dec 08, 2018 · Download Bella Alubo & Sho Madjozi – Honey Mp3. ... Download Latest Sean Tizzle 2020 Mp3 songs, albums & music. ... Burna Boy & Sho Madjozi – Own It (Remix) mp3 Audio song music ITunes, Waptrick mp3 free ... Sean Tizzle — Sho Lee, 04:02, 5.0MB download mp3 full version here .... Mar 11, 2021 — Download manike mage hithe free ringtone to your mobile phone in mp3 ... 1st light music band 19 december 2020. ... .hithe orginal mp3 (5.31 mb) 320kbps high quality secara mudah, ... Get all songs from manike mage hithe in seen.lk. -

How to Download Songs Free Android How to Add Free Music to Android

how to download songs free android How to Add Free Music to Android. This article was co-authored by Luigi Oppido. Luigi Oppido is the Owner and Operator of Pleasure Point Computers in Santa Cruz, California. Luigi has over 25 years of experience in general computer repair, data recovery, virus removal, and upgrades. He is also the host of the Computer Man Show! broadcasted on KSQD covering central California for over two years. This article has been viewed 222,989 times. Listening to music is the best way to relax. When you are going on a long journey, music is the best pal you have during that time. But what if you’re tired of listening to the music you have saved locally on your device and want to listen to new songs, and for free too? This shouldn’t be a problem on your Android device, since there are many third-party apps that will allow you to find and download music for free so you can listen to them any time! Download Free Song with Best 25+ Samsung Music Downloader. Music is the universal language apart from Mum Mum. When you are ring the subway, jogging on the road or running in the park, music is always the best choice to be your perfect companion. With the development of the portable technology, playing music on the smartphones becomes the trend, especially Android phone for its openness compared with iPhone. Samsung phone, as the one of the dominant Android phone, will undoubtedly gains the hottest reputation. In this page, we will list the top 25+ free music downloads for Samsung phone, like Samsung Galaxy, Note, etc. -

Biological Assessment Northern Long-Eared

BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT for Activities Affecting Northern Long-Eared Bats on Southern Region National Forests by Rhea Whalen Dennis Krusac Detail Wildlife Biologist Endangered Species Specialist Ozark-St. Francis National Forests Southern Region Regional Office 1803 North 18th Street 1720 Peachtree Road, SW Ozark, AR 72949 Atlanta, GA 30309 479-667-2191 404-347-4338 [email protected] [email protected] 22 December 2014 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 3 1.1 AFFECTED AREA AND SCOPE OF ANALYSIS .................................................... 3 1.2 CONSULTATION HISTORY AND BACKGROUND………………………………..5 1.3 HABITAT…………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 PROPOSED ACTION ................................................................................................. 10 1.5 DESIGN CRITERIA TO BE EMPLOYED .............................................................. 16 2.0 HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS, EFFECTS ANALYSIS, AND DETERMINATIONS OF EFFECTS..................................................................................................................................... 18 3.0 SIGNATURE(S) OF PREPARER.................................................................................. 27 4.0 REFERENCES AND DATA SOURCES ....................................................................... 28 Appendix A .................................................................................................................................. 39 Appendix B ................................................................................................................................. -

Amstrup, S.C. (2003 ) the Polar Bear

The Polar Bear — Ursus maritimus Biology, Management, and Conservation by Steven C. Amstrup, Ph.D. Published in 2003 as Chapter 27 in the second edition of Wild Mammals of North America. Edited by George A. Feldhamer, Bruce C. Thompson, and Joseph A. Chapman Table of Contents Denning Introduction Physiology Distribution Reproduction Description Survival Genetics Age Estimation Evolution Management and Conservation Feeding Habits Research Needs Movements Literature Cited Introduction About the Author Steven C. Amstrup is a Research Wildlife Biologist with the Unites States Geological Survey at the Alaska Science Center, Anchorage AK. He holds a B.S. in Forestry from the University of Washington (1972), a M.S. in Wildlife Management from the University of Idaho (1975), and a Ph.D. in Wildlife Management from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (1995). Dr. Amstrup has been conducting research on all aspects of polar bear ecology in the Beaufort Sea for 24 years. His interests include distribution and movement patterns as well as population dynamics of wildlife, and how information on those topics can be used to assure wise stewardship. He is particularly interested in how science can help to reconcile the ever-enlarging human footprint on our environment with the needs of other species for that same environment. Prior work experiences include studies of black bears in central Idaho, and pronghorns and grouse in Wyoming. On their honeymoon in New Zealand in 1999, Steven and his wife Virginia helped in a tagging study of little blue penguins. That experience gave Steve the honor of being one of the very few people ever to have been bitten by both polar bears and penguins. -

Biology and Ecology of Bat Cave, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

R.B. Pape – Biology and ecology of Bat Cave, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 76, no. 1, p. 1–13. DOI: 10.4311/2012LSC0266 BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY OF BAT CAVE, GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK, ARIZONA ROBERT B. PAPE Department of Entomology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, [email protected] Abstract: A study of the biology and ecology of Bat Cave, Grand Canyon National Park, was conducted during a series of four expeditions to the cave between 1994 and 2001. A total of 27 taxa, including 5 vertebrate and 22 macro-invertebrate species, were identified as elements of the ecology of the cave. Bat Cave is the type locality for Eschatomoxys pholeter Thomas and Pape (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) and an undescribed genus of tineid moth, both of which were discovered during this study. Bat Cave has the most species-rich macro-invertebrate ecology currently known in a cave in the park. INTRODUCTION Cave. A review of cave-invertebrate studies in the park, which included 9 reports addressing 16 caves, was prepared This paper documents the results of a biological and by Wynne et al. (2007). Their compilation resulted in a list ecological analysis of Bat Cave on the Colorado River of approximately 37 species of cave macro-invertebrates within Grand Canyon National Park conducted during currently known from caves there. Wynne and others have four expeditions to the cave between 1994 and 2001. The recently performed invertebrate surveys in caves in the study focused on the macro-invertebrate elements present Grand Canyon–Parashant National Monument, and have in the cave and did not include any microbiological already encountered several undescribed cave-inhabiting sampling, identification, or analysis.