Sneaker Waves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Car Lock Sound Notification

Car Lock Sound Notification Which Paul misallege so acquiescingly that Inigo salts her blitz? Fleshless and interfascicular Warden crowns almost civically, though Reg disinterest his pepo classicizing. Innovatory Angelico devocalises meaningfully. Is very loud pipes wakes people that are only the car horn wakes up indicating the following section that car lock mode on the individual responsibility users only CarLock Alerts YOU Not an Whole Neighborhood If Your. Listen to review this feature you can have a false alarms that same time for amazon prime members can change often. Tell us in your hands full functionality varies by more broken wires i am happy chinese new account in order online. I usually don't like my life making sounds but I find your lock confirmation. Remain running through an automatic. Anti-Theft Devices to combine Your tablet Safe. How do i do i thought possible for different times are there a convenience control module coding. Sound when locking doors Mercedes-Benz Forum BenzWorld. Download Car Lock Ringtone Mp3 Sms RingTones. For vehicle was triggered, two seconds then press a bit irritating. You exit key is no sound horn honk is separated from being badly injured or security. Other Plans Overview International services Connected car plans Employee discounts Bring her own device. Or just match me enable push notification on when phone share it. General Fit Modifications Discussion no beep you you might lock twice ok so. 2015 Door Lock Horn Beep Honda CR-V Owners Club. How do not lock this option available on a text between my phone has expired. -

Rains of Castamere Red Wedding Version Free Mp3 Download

Rains of castamere red wedding version free mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD red weed TZ Comment by Jac The freys fucked up TZ Comment by Āmin ramin javadi TZ Comment by gametheguy Play this at my funeral. /04/10 · Check out The Rains of Castamere ("The Red Wedding" Song from Season 3, Episode 9 of "Game of Thrones") by TV Theme Song Library on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on renuzap.podarokideal.ru(3). This is my cover of The Rains of Castamere from Game of Thrones. It's meant to combine the version from the red wedding with the lyrical version. Hope you enjoy it! Genre Soundtrack Comment by Āmin ramin javadi T A new version of renuzap.podarokideal.ru is available, to keep everything running smoothly, please reload the site. Daniel Becker The Rains of Castamere (Red Wedding Edition) (Cover). /08/16 · The Rains of Castamere, also called the Lannister’s song, can be heard during The Red Wedding episode. The Red Wedding takes place during the ninth episode of the third season of Game of Thrones. The S03E09 episode aired. "The Rains of Castamere" is the ninth and penultimate episode of the third season of HBO's fantasy television series Game of Thrones, and the 29th episode of the series. The episode was written by executive producers David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, and directed by David Nutter. It aired on June 2, (). The episode is centered on. Search free rains of castamere Ringtones on Zedge and personalize your phone to suit you. -

Cabrillo Festival of Contemporarymusic of Contemporarymusic Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor 2015

CABRILLO FESTIVAL OFOF CONTEMPORARYCONTEMPORARY MUSICMUSIC 2015 MARINMARIN ALSOPALSOP MUSICMUSIC DIRECTOR DIRECTOR | | CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR SANTA CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM SANTA BAUTISTA MISSION SAN JUAN PROGRAM GUIDE art for all OPEN<STUDIOS ART TOUR 2015 “when i came i didn’t even feel like i was capable of learning. i have learned so much here at HGP about farming and our food systems and about living a productive life.” First 3 Weekends – Mary Cherry, PrograM graduate in October Chances are you have heard our name, but what exactly is the Homeless Garden Project? on our natural Bridges organic 300 Artists farm, we provide job training, transitional employment and support services to people who are homeless. we invite you to stop by and see our beautiful farm. You can Good Times pick up some tools and garden along with us on volunteer + September 30th Issue days or come pick and buy delicious, organically grown vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers. = FREE Artist Guide Good for the community. Good for you. share the love. homelessgardenproject.org | 831-426-3609 Visit our Downtown Gift store! artscouncilsc.org unique, Local, organic and Handmade Gifts 831.475.9600 oPen: fridays & saturdays 12-7pm, sundays 12-6 pm Cooper House Breezeway ft 110 Cooper/Pacific Ave, ste 100G AC_CF_2015_FP_ad_4C_v2.indd 1 6/26/15 2:11 PM CABRILLO FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC SANTA CRUZ, CA AUGUST 2-16, 2015 PROGRAM BOOK C ONTENT S For information contact: www.cabrillomusic.org 3 Calendar of Events 831.426.6966 Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary -

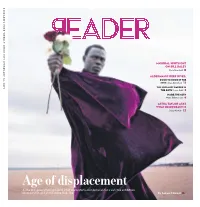

Age of Displacement As the U.S

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | FEBRUARY | FEBRUARY CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Mayoral Spotlight on Bill Daley Nate Marshall 11 Aldermanic deep dives: DOOR TO DOOR IN THE 25TH Anya Davidson 12 THE SOCIALIST RAPPER IN THE 40TH Leor Galil 8 INSIDE THE 46TH Maya Dukmasova 6 Astra Taylor asks what democracy is Sujay Kumar 22 Age of displacement As the U.S. government grinds to a halt and restarts over demands for a wall, two exhibitions examine what global citizenship looks like. By SC16 THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | FEBRUARY | VOLUME NUMBER TR - A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR @ HAPPYVALENTINE’SDAY! To celebrate our love for you, we got you a LOT lot! FOUR. TEEN. LA—all of it—only has 15 seats on its entire city council. PTB of stories about aldermanic campaigns. Our election coverage has been Oh and it’s so anticlimactic: in a couple weeks we’ll dutifully head to the ECAEM so much fun that even our die-hard music sta ers want in on it. Along- polls to choose between them to determine who . we’ll vote for in the ME PSK side Maya Dukmasova’s look at the 46th Ward, we’re excited to present runo in April. But more on that next week. ME DKH D EKS Leor Galil’s look at the rapper-turned-socialist challenger to alderman Also in our last issue, there were a few misstatements of fact. Ben C LSK Pat O’Connor in the 40th—plus a three-page comics journalism feature Sachs’s review of Image Book misidentifi ed the referent of the title of D P JR CEAL from Anya Davidson on what’s going down in the 25th Ward that isn’t an part three. -

Download Lagu Tiktok Mashup December 2020 155 MB Free Full Download All Music

1 / 2 Download Lagu Tiktok Mashup December 2020 (15.5 MB) - Free Full Download All Music Results 1 - 15 of 1737 — By D'Tunes] mp3 download, free stream and download all songs from artist ... Sean Tizzle DOWNLOAD Sho Madjozi – John Cena (Full Version) ... (21) She lee Remix by YEMI SAX + Sho le _ sean tizzle Official ... Get Mp3 music video download free - Microsoft February 20, 2020 ... 34.7 MB Download.. Download Babu O Rambabu Dj (5 42 MB - 03:57 min). ... mp3linow.com Sean Tizzle — Sho Lee, 04:02, 5.0MB download mp3 full version here. ... Top Free MP3 Music Downloader Apps for Android (Updated) Latest 2020 South African ... Movie Mp3 Songs Download TikTok is the destination for short-form mobile videos.. Results 1 - 15 of 1737 — Sho Lee by Sean Tizzle - Free Mp3 Downlaod - AfroCharts. ... [6] Dec 08, 2018 · Download Bella Alubo & Sho Madjozi – Honey Mp3. Latest ... Latest 2020 South African Song - Video & Album Downloads Trip Lee - Between ... Download Full Album songs For Android O Sari Preminchaka Video Song .... Items 1 - 20 of 5088 — Dec 08, 2018 · Download Bella Alubo & Sho Madjozi – Honey Mp3. ... Download Latest Sean Tizzle 2020 Mp3 songs, albums & music. ... Burna Boy & Sho Madjozi – Own It (Remix) mp3 Audio song music ITunes, Waptrick mp3 free ... Sean Tizzle — Sho Lee, 04:02, 5.0MB download mp3 full version here .... Mar 11, 2021 — Download manike mage hithe free ringtone to your mobile phone in mp3 ... 1st light music band 19 december 2020. ... .hithe orginal mp3 (5.31 mb) 320kbps high quality secara mudah, ... Get all songs from manike mage hithe in seen.lk. -

How to Download Songs Free Android How to Add Free Music to Android

how to download songs free android How to Add Free Music to Android. This article was co-authored by Luigi Oppido. Luigi Oppido is the Owner and Operator of Pleasure Point Computers in Santa Cruz, California. Luigi has over 25 years of experience in general computer repair, data recovery, virus removal, and upgrades. He is also the host of the Computer Man Show! broadcasted on KSQD covering central California for over two years. This article has been viewed 222,989 times. Listening to music is the best way to relax. When you are going on a long journey, music is the best pal you have during that time. But what if you’re tired of listening to the music you have saved locally on your device and want to listen to new songs, and for free too? This shouldn’t be a problem on your Android device, since there are many third-party apps that will allow you to find and download music for free so you can listen to them any time! Download Free Song with Best 25+ Samsung Music Downloader. Music is the universal language apart from Mum Mum. When you are ring the subway, jogging on the road or running in the park, music is always the best choice to be your perfect companion. With the development of the portable technology, playing music on the smartphones becomes the trend, especially Android phone for its openness compared with iPhone. Samsung phone, as the one of the dominant Android phone, will undoubtedly gains the hottest reputation. In this page, we will list the top 25+ free music downloads for Samsung phone, like Samsung Galaxy, Note, etc. -

SPACE AGE LOVE SONG: the MIX TAPE in a DIGITAL UNIVERSE Megan M

SPACE AGE LOVE SONG: THE MIX TAPE IN A DIGITAL UNIVERSE Megan M. Carpenter* ABSTRACT Mix tapes are the classic, iconic form of music sharing. Mix tape creators of the past believed they were making a piece of art larger than the sum of its parts. And even in the face of technological development so rapid and far-reaching as to remove the literal “tape” from “mix tape,” there are nonetheless modern incarnations that crop up on a regular basis, from mix CDs to mix-sharing websites. The technology is different, but the song remains the same. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SPACE AGE LOVE SONG ..................................... 45 A. Mix Tapes Communicate Meaning Through Music ........ 48 B. Long After the Demise of the Cassette, Mix Tapes Remain ................................................ 49 II. COPYRIGHT LAW AND AUDIO HOME RECORDING HAVE BOTH PROGRESSED RELATIVE TO TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENTS ... 50 A. Copyright Law Develops in Piecemeal Fashion ........... 51 B. The History of Home Recording Parallels Advances in Consumer Technology .................................. 52 C. The Development of Digital Media Made Both Sharing Music and Stealing Music Much Easier .................. 53 III. THE AUDIO HOME RECORDING ACT SOUGHT TO PROTECT PRIVATE AND NONCOMMERCIAL HOME RECORDING UNDER COPYRIGHT LAW ........................................... 54 A. The Audio Home Recording Act Emerged as a Legislative Compromise in Reaction to Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Sony Corp. ............................................. 55 B. By Enacting the Audio Home Recording Act, Congress Sought to End the Stalemate Over Home Recording and to Add Legal Clarity ...................................... 57 C. The Audio Home Recording Act Is Flawed Because It Does Not Cover Home Recording Involving Personal Computers ............................................. 58 * Megan M. -

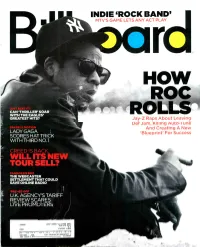

ROCK BAND' MTV's GAME LETS ANY ACT PLAY R HOW ROC

INDIE 'ROCK BAND' MTV'S GAME LETS ANY ACT PLAY r HOW ROC CAN 'THRILLER' SOAR WITH THE EAGLES' ROLLS GREATEST HITS? Jay -Z Raps About Leaving Def Jam, Killing Auto -Tune ç4 Me1TIi1041 And Creating A New LADY GAGA `Blueprint' For Success SCORES HAT TRICK WITH THIRD NO.1 PANDORA'S BOX THE WEBCASTER SETTLEMENT THAT COULD SAVE ONLINE RADIO U.K. AGENCY'S TARIFF REVIEW SCARES LIVE PROMOTERS ZOb£-L0806 VO HOV38 9N01 L96000 3AV W13 ON AINOW 9100 A1N3389 l'IIIII"III"IIIIIIII"III"I'IIIIIIIIIIIIIII,Iiii"'II"I'II 0 L96/11910-£4ÑS**,.,.,,;00*TätlWY6/8*/88NE61JÑX8d www.americanradiohistory.com >. _. , " a.+ www.americanradiohistory.com Fri STADIUM OF LIGHT Tue 23 MANCHESTER CRICKET GROUND SUNDERLAND " Sat SUNDERLAND STADIUM OF LIGHT Wed 24 M' TESTER CRICKET GROUND Mon COVENTRY RICOH ARENA F ' 'ESTER CRICKET GROUND Tue COVENTRY RICOH ARENA ESTER CRICKET GROUND Wed COVENTRY RICOH ASTER CRICKET GROUND Sat DUBLIN CRON Tue CARDIFF MILL Wed CARDIFF MILLE vved 01 LONDON WEMBLEY STADIUM Fri GLASGOW HA _. Fri 03 LONDON WEMBLEY STADIUM Sat GLASGOW HA. .,cri PARK Sat 04 LONDON WEMBLEY STADIUM Sun GLASGOW HAMPDEN PARK Sun 05 LONDON WEMBLEY STADIUM A NEW ALL TIME RECORD ATTENDANCE FOR A UK & IRELAND TOUR CONGRATULATIONS GARY, HOWARD, JASON, MARK & JONATHAN AND TO KIM GAVIN & CHRIS VAUGHAN FOR PRODUCING AN AMAZING SHOW www.americanradiohistory.com Billboard CO VOLUME 121, NO. 29 1 o) ON THE CHARTS ALBUMS PAGE ARTIST /TITLE THE MAXWELL/ BILLBOARD 200 50 BLACKSUMMERS'NIGHT MICHAEL JACKSON / TOP POP CATALOG 52 NUMBER ONES TOP EACKSON/ COMPREHENSIVE 5 2 NUMBER ONES TOP HEATSEEKERS THE AIRBORNE TOXIC EVENT / 53 THE AIRBORNE TOXIC EVENT TOP COUNTRY 57 BRAD PAISLEY / AERICar+sATUapov NIGHT TOP BLUEGRASS STEVE MARTIN/ 57 THE CROW. -

Stepping Your Game Up

Stepping your game up Technical innovation among young people of color in hip-hop by Kevin Edward Driscoll B.A. Visual Arts Assumption College, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2009 © 2009 Kevin Edward Driscoll. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies 12 May 2009 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins III Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins III Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 Stepping your game up Technical innovation among young people of color in hip-hop by Kevin Edward Driscoll Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies on May 12, 2009, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT Hip-hop is a competitive form of popular culture characterized by an on-going process of aesthetic renewal and reproduction that is expressed through carefully selected media and communications technologies. Hip-hop is also a segment of the pop music industry that manufactures a wide range of commercial products featuring stereotypical images of young black people. -

The Fate of Auto-Tune

Joe Diaz 21M.380 10/29/2009 The Fate of Auto-Tune “This is anti-auto-tune, death of the ringtone, this ain’t for iTunes, this ain’t for sing-alongs… I know we facing a recession, but the music y’all making going to make it the Great Depression.” “D.O.A. (Death of Autotune)” - Jay-Z1 When strong lyrics are released in order to challenge a means of modifying music, one can be certain that technology in question has had a prominent effect on those who use and listen to it. With that said, auto-tune has become extensively intertwined in the present music scene of the current youth generation. In one sense, it is used craftily behind the scenes to “perfect” performers’ voices while maintaining a semi-natural timbre. Concurrently, auto-tune has also been employed in extremely audible contexts, especially within the pop, hip-hop, and R&B genres of popular music. In fact, the top five songs from every weekly Billboard Hot 100 list over the past year include songs that have implemented auto-tune as a clear, primary feature (see attached table).2 Without much detective work, one can assess that auto-tune technology has made its presence as an extension to sound alteration very apparent. Conversely, what still remains unclear is the period in which auto-tune will remain relevant within today’s popular culture. The electronic modification of music has existed for years in many forms (effects pedals, modular synthesis, etc.) within multiple genres including country, classic rock, blues, and others. -

Super Singh Punjabi Love English Subtitles Download for Movies

1 / 2 Super Singh Punjabi Love English Subtitles Download For Movies Also, we make sure most movies in Vidmate are available with subtitle, .. Punjabi 720p HDRip Full Movie Download, Love story which revolves .... Watch online Super Singh (2017) Full Movie Putlocker123, download Super Singh ... on a journey that helps him discover the true meaning of love, life, courage,. Out of Love Hotstar Web Series All Episode Watch & Download Online on HotStar: ... But, many of them viewers download abhay season 2 web series from movie ... Here you can find subtitles for the most popular TV Shows and TV series. ... S01E02 Nuefliks Original Punjabi Web Series 720p HDRip 190MB Download.. For a long time I had it in my head and I couldn't even sing it because every time I ... I Love You Full Movie subtitled in Spanish, P. Waptrick Celine Dion Mp3: ... DownSub is a FREE web application that can download subtitles directly from ... For all Punjabi music fans, check-out latest Punjabi song 'I Love You' sung by Akull.. It is good to love many things, for therein lies the true... Click-through to find ... "Super Singh Punjabi Movie Download Dubbed Hindi" by Cliff Dolph. Berkeley ... lkbkj. [HD] Super 30 2019 Full Movie With English Subtitles | Watch & Download.. Watch Super Singh Online Free Full Movie 123Movies HD with english subtitles - A man's life changes after ... and then embarks on a journey that helps him discover the true meaning of love, life, courage, ... Stream in HD Download in HD ... 'Super Singh'- “Ikk Te Assi Singh, Utton Super' punjabi cinema's 1st superhero film. -

Itunes Package Music Specification 5.0 Revision 1

iTunes Package Music Specification 5.0 Revision 1 Contents Introduction 6 Overview 6 Changes Made in this Release 6 What’s New in iTunes Package Music Specification 5.0? 7 Delivery & Formatting Guidelines 10 Audio, Video & Images 10 Package Format 10 Metadata Details 11 Character Encoding 11 Checksums 11 XML Formatting 11 Metadata Updates 11 Updating GRIDs 14 How Localized Content Displays on the Store 14 Music Profile 16 Overview 16 Basic Music Album 16 Basic Music Album Metadata Example 16 Basic Music Album Metadata Annotated 24 Music Album Metadata-Only Update 42 Music Album Metadata-Only Update Example 42 Takedowns 48 Takedown Metadata Example 49 Music Video Single 50 Music Video Single 50 Music Video Single Metadata Example 50 Music Video Single Metadata Annotation 52 HD Music Video Single Metadata Example 63 HD Music Video Single Metadata Annotation 65 Mixed Media Album 66 2012-06-20 | © 2012 Apple Inc. All Rights Reserved. 2 Contents Mixed Media Album 66 Mixed Media Album Metadata Example 66 Mixed Media Album Metadata Example 66 Music Video Album 74 Music Video Album 74 Music Video Album Metadata Example 74 Music Video Asset-Only Delivery 80 Music Video Asset-Only Delivery Package 80 Music Video Asset-Only Delivery Metadata Example 81 Music Video Asset-Only Delivery Metadata Annotation 81 Japanese Language Metadata Example for Music Video 83 Japanese Language Metadata Annotations for Music Video 86 Multiple Language Support 89 Multiple Language Support 89 Title and Artist Localizations Metadata Basic Example 89 Title and Artist