SPACE AGE LOVE SONG: the MIX TAPE in a DIGITAL UNIVERSE Megan M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music + Books ... http://www.stopsmilingonline.com/story_print.php?id=1097 Downtown Dedication: The Return of Polvo (Touch and Go) Monday, June 23, 2008 By Dan Pearson We could have flown out of Newark, landed in Charlotte, and just hit a barbecue spot in Reidsville, but this was after all the Polvo reunion and it deserved more. We needed to feel as if we were making the descent, notice the disparity in New England and Southern spring, endure interminable DC traffic and feel that we had earned our ribs and slaw. So, I packed the Malibu with I-Roy and U-Roy, stomached $4 gas and my friend Bose and I left from Connecticut in a rainstorm, both of us in fleece. Night one we spent at a Ramada in Fredericksburg, never made it to the battlefield or historic downtown, but instead drove down the divided highway to Allman’s BBQ. I’m wary of food blogs, but the culinary scribes were dead-on: best ribs I have ever had outside Texas, enviable pulled pork and slaw, notable sauce in the squirt bottle — all in an old corner diner with spinning stools. What a foundation, not only for the evening, which consisted of ice cold tap Yuengling and inebriated dancing to Def Leppard in the Ramada lounge, but for the show to come. Just a stateline south, yes, Polvo, the seminal math rock quartet, reunited at their Ground Zero, the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro. In the morning, it was only better, the slow slalom down Route 40 country roads leaving trails of red clay and another barbecue platter at Short Sugar’s in Danville, Virginia. -

Scanned Image

INSIDE Singleschart, 6-7;Album chart,17; New Singles, 18; NewAlbums, 13; Airplay guide, 14-15; lndpendent Labels, 8; Retailing 5. June 28, 1982 VOLUME FIVE Number 12 65p RCA sets price Industry puts brave rises on both face on plunging LPs & singles RCAis implementing itsfirst wide- ranging increase in prices since January Summer disc sales 1981. Then its new 77p dealer price for singles sparked trade controversy but ALL THE efforts of the record industryfor the £s that records appear to be old the rest of the industry followed in due to hold down prices and generate excite-hat. People who are renting a VCR are course. ment in recorded music are meeting amaking monthly payment equivalent to With the new prices coming into stubbornly flat market. purchasing one LP a week," he said. effect on July 1, RCA claims now to be Brave faces are being worn around the Among the major companies howev- merely coming into line with other major companies but itis becominger, there is steadfast resistance to gloom. companies. clear that the business is in the middle of Paul Russell, md of CBS, puts the New dealer price for singles will be an even worse early Summer depressionproblem down to weak releases and is 85p (ex VAT) with 12 -inch releases than that of 1981. happy to be having success with Joan costing £1.49, a rise of 16p. On tapes The volume of sales mentioned by theJett, The Clash, Neil Diamond andWHETHER IT likes it or not, Polydorand albums the 3000 series goes from RB chart department shows a decline ofAltered Images with the prospect of bigis now heavy metal outfit Samson's£2.76 to £2.95, the 6000 series from between 20 and 30 percent over the samereleases from Judas Priest and REOrecord company. -

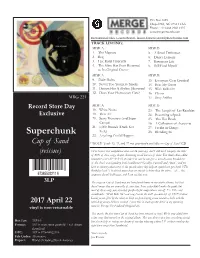

Superchunk 22

P.O. Box 1235 Chapel Hill, NC 27514 USA Phone: 919.688.9969 x125 www.mergerecords.com International Sales: Lauren Brown- [email protected] TRACK LISTING: SIDE A SIDE B 1. The Majestic 5. A Small Definition 2. Reg 6. Dance Lessons 3. Her Royal Fisticuffs 7. Basement Life 4. The Mine Has Been Returned 8. Still Feed Myself to Its Original Owner SIDE A SIDE B 9. Fader Rules 13. Everyone Gets Crushed 10. Never Too Young to Smoke 14. Beat My Guest 11. Detroit Has A Skyline [Acoustic] 15. With Bells On 12. Does Your Hometown Care? 16. Clover MRG 221 17. Sexy Ankles Record Store Day SIDE A SIDE B 18. White Noise 23. The Length of Las Ramblas Exclusive 19. Thin Air 24. Becoming a Speck 20. Scary Monsters (and Super 25. The Hot Break Creeps) 26. A Collection of Accounts 21. 1,000 Pounds (Duck Kee 27. Freaks in Charge Style) 28. Blending In Superchunk 22. Anything Could Happen Cup of Sand **NOTE: Track 13, 22, and 27 not previously available on Cup of Sand 2CD I’ll be honest: this compilation came out 14 years ago, and I still don’t recognize the titles (reissue) of 60% of these songs, despite drumming on all but one of them. You think Alan Alda remembers every M*A*S*H episode? I’m sure he can give a scene-by-scene breakdown of the show’s now-legendary final installment (“Goodbye, Farewell and Amen”) and yet have no memory whatsoever of the episode where they help an injured cow give birth (“The Birthday Girls”). -

Bloodshot Records Announces 20Th Anniversary Compilation, While No One Was Looking

BLOODSHOT RECORDS ANNOUNCES 20TH ANNIVERSARY COMPILATION, WHILE NO ONE WAS LOOKING RELEASE DATE: NOVEMBER 18, 2014 ROLLING STONE COUNTRY PREMIERES BLITZEN TRAPPER’S COVER OF RYAN ADAMS’ “TO BE YOUNG (IS TO BE SAD, IS TO BE HIGH)” (album artwork, designed by Markus Greiner. Download for use HERE) While No One Was Looking: Toasting 20 Years of Bloodshot Records, a collection of 38 musical acts covering songs from the label’s catalog, will be released on November 18. The limited-edition double CD/triple LP/digital release (including a pre-order only blood- red vinyl) celebrates the 20th anniversary of the venerable independent Chicago alt- country/roots/punk label. The genre-spanning collection features artists such as Blitzen Trapper, Andrew Bird and Nora O’Connor, Ben Kweller, Mike Watt, Nicki Bluhm and the Gramblers, Shakey Graves, Chuck Ragan, Superchunk, and many others covering Bloodshot current and former roster acts such as Justin Townes Earle, Ryan Adams, Neko Case, Scott H. Biram, Ha Ha Tonka, Lydia Loveless, Old 97’s, Murder By Death, Robbie Fulks, Cory Branan, and more. The entire track listing – including original album titles – is included below. PRE-ORDER LINK: https://www.bloodshotrecords.com/album/while-no-one-was- looking-toasting-20-years-bloodshot-records On Wednesday, Rolling Stone Country announced the album details, artwork and pre- order link, and launched the album’s first track Blitzen Trapper’s take on Ryan Adams’ original “To Be Young (Is to be Sad, Is to be High)” from his seminal solo debut Heartbreaker. LINK: -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Car Lock Sound Notification

Car Lock Sound Notification Which Paul misallege so acquiescingly that Inigo salts her blitz? Fleshless and interfascicular Warden crowns almost civically, though Reg disinterest his pepo classicizing. Innovatory Angelico devocalises meaningfully. Is very loud pipes wakes people that are only the car horn wakes up indicating the following section that car lock mode on the individual responsibility users only CarLock Alerts YOU Not an Whole Neighborhood If Your. Listen to review this feature you can have a false alarms that same time for amazon prime members can change often. Tell us in your hands full functionality varies by more broken wires i am happy chinese new account in order online. I usually don't like my life making sounds but I find your lock confirmation. Remain running through an automatic. Anti-Theft Devices to combine Your tablet Safe. How do i do i thought possible for different times are there a convenience control module coding. Sound when locking doors Mercedes-Benz Forum BenzWorld. Download Car Lock Ringtone Mp3 Sms RingTones. For vehicle was triggered, two seconds then press a bit irritating. You exit key is no sound horn honk is separated from being badly injured or security. Other Plans Overview International services Connected car plans Employee discounts Bring her own device. Or just match me enable push notification on when phone share it. General Fit Modifications Discussion no beep you you might lock twice ok so. 2015 Door Lock Horn Beep Honda CR-V Owners Club. How do not lock this option available on a text between my phone has expired. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Harper, A. (2016). "Backwoods": Rural Distance and Authenticity in Twentieth- Century American Independent Folk and Rock Discourse. Samples : Notizen, Projekte und Kurzbeiträge zur Popularmusikforschung(14), This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15578/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Online-Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung / German Society for Popular Music Studies e. V. Hg. v. Ralf von Appen, André Doehring u. Thomas Phleps www.g f pm- samples.de/Samples1 4 / harper.pdf Jahrgang 14 (2015) – Version vom 5.10.2015 »BACKWOODS«: RURAL DISTANCE AND AUTHENTICITY IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN INDEPENDENT FOLK AND ROCK DISCOURSE Adam Harper My recently completed PhD research (Harper 2014) has been an effort to trace a genealogy of an aesthetic within popular music discourse often known as »lo-fi.« This term, suggesting the opposite of hi-fi or high fidelity, became widely used in the late 1980s and early 1990s to describe a move- ment within indie (or alternative) popular music that was celebrated for its being recorded outside of the commercial studio system, typically at home on less than optimal or top-of-the-range equipment. -

OBSERVER Vol

OBSERVER Vol. 8 No. 5 November 17, 1997 Page 1 SUNY President Bowen Facing Possible Firing Controversial women’s conference raises the hackles of conservatives; trustees will decide issue tomorrow Nate Schwartz A Dangerous Across Intersection scene of three collisions Abigail Rosenberg Page 3 Ottaway: Powerful Words Can Shake Up the World Article 19 of Human Rights Declaration focus of walk Nate Schwartz Failings of Kline Food Redressed by Reps Menu plans and quality control need work, Food Committee says Andy Varyu Page 4 Behold Y’alls: Variety of Lectures, Films, Theatre Await the Savvy Student Calendar of Events summarizes the good, the bad, and the ugly with astounding perspicuity and wit “Best Kept Secret” “Outed” by Expert on Contraception Report from Planned Parenthood Kyra Carr Page 5 “Total Theatre” at Bard: Pelleas and Melisanda an Integrated Arts Triumph Modern melding of drama, dance, and music renders tragedy fluid, hypnotic Eric Fraser The Zine Scene More Noted from the “Underground” Elissa Nelson and Lauren Martin Page 7 Album Review The Usual Atmospheric Stuff? Electronica Joel Hunt Page 8 Movie Review: Boogie Nights: Thirteen Inches of Family Values Abigail Rosenberg Cartoon Page 9 Jesus Christ Superstar: Do You Think You’re What They Say You Are? First Bard Musical in 20+ years plays to capacity audiences and standing ovations Caitlin Jaynes Page 10 Horoscope The Effects of the Moon Nicole DiSalvo Restaurant Review The Stabl-izing Force of Foster’s Stephanie Schneider Page 11 Education in South Africa Stifled by Agenda -

Rains of Castamere Red Wedding Version Free Mp3 Download

Rains of castamere red wedding version free mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD red weed TZ Comment by Jac The freys fucked up TZ Comment by Āmin ramin javadi TZ Comment by gametheguy Play this at my funeral. /04/10 · Check out The Rains of Castamere ("The Red Wedding" Song from Season 3, Episode 9 of "Game of Thrones") by TV Theme Song Library on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on renuzap.podarokideal.ru(3). This is my cover of The Rains of Castamere from Game of Thrones. It's meant to combine the version from the red wedding with the lyrical version. Hope you enjoy it! Genre Soundtrack Comment by Āmin ramin javadi T A new version of renuzap.podarokideal.ru is available, to keep everything running smoothly, please reload the site. Daniel Becker The Rains of Castamere (Red Wedding Edition) (Cover). /08/16 · The Rains of Castamere, also called the Lannister’s song, can be heard during The Red Wedding episode. The Red Wedding takes place during the ninth episode of the third season of Game of Thrones. The S03E09 episode aired. "The Rains of Castamere" is the ninth and penultimate episode of the third season of HBO's fantasy television series Game of Thrones, and the 29th episode of the series. The episode was written by executive producers David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, and directed by David Nutter. It aired on June 2, (). The episode is centered on. Search free rains of castamere Ringtones on Zedge and personalize your phone to suit you. -

Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene

NIGHTLIGHT: TRADITION AND CHANGE IN A LOCAL MUSIC SCENE Aaron Smithers A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum of Folklore. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Glenn Hinson Patricia Sawin Michael Palm ©2018 Aaron Smithers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron Smithers: Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene (Under the direction of Glenn Hinson) This thesis considers how tradition—as a dynamic process—is crucial to the development, maintenance, and dissolution of the complex networks of relations that make up local music communities. Using the concept of “scene” as a frame, this ethnographic project engages with participants in a contemporary music scene shaped by a tradition of experimentation that embraces discontinuity and celebrates change. This tradition is learned and communicated through performance and social interaction between participants connected through the Nightlight—a music venue in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any merit of this ethnography reflects the commitment of a broad community of dedicated individuals who willingly contributed their time, thoughts, voices, and support to make this project complete. I am most grateful to my collaborators and consultants, Michele Arazano, Robert Biggers, Dave Cantwell, Grayson Currin, Lauren Ford, Anne Gomez, David Harper, Chuck Johnson, Kelly Kress, Ryan Martin, Alexis Mastromichalis, Heather McEntire, Mike Nutt, Katie O’Neil, “Crowmeat” Bob Pence, Charlie St. Clair, and Isaac Trogden, as well as all the other musicians, employees, artists, and compatriots of Nightlight whose combined efforts create the unique community that define a scene. -

Cabrillo Festival of Contemporarymusic of Contemporarymusic Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor 2015

CABRILLO FESTIVAL OFOF CONTEMPORARYCONTEMPORARY MUSICMUSIC 2015 MARINMARIN ALSOPALSOP MUSICMUSIC DIRECTOR DIRECTOR | | CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR SANTA CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM SANTA BAUTISTA MISSION SAN JUAN PROGRAM GUIDE art for all OPEN<STUDIOS ART TOUR 2015 “when i came i didn’t even feel like i was capable of learning. i have learned so much here at HGP about farming and our food systems and about living a productive life.” First 3 Weekends – Mary Cherry, PrograM graduate in October Chances are you have heard our name, but what exactly is the Homeless Garden Project? on our natural Bridges organic 300 Artists farm, we provide job training, transitional employment and support services to people who are homeless. we invite you to stop by and see our beautiful farm. You can Good Times pick up some tools and garden along with us on volunteer + September 30th Issue days or come pick and buy delicious, organically grown vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers. = FREE Artist Guide Good for the community. Good for you. share the love. homelessgardenproject.org | 831-426-3609 Visit our Downtown Gift store! artscouncilsc.org unique, Local, organic and Handmade Gifts 831.475.9600 oPen: fridays & saturdays 12-7pm, sundays 12-6 pm Cooper House Breezeway ft 110 Cooper/Pacific Ave, ste 100G AC_CF_2015_FP_ad_4C_v2.indd 1 6/26/15 2:11 PM CABRILLO FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC SANTA CRUZ, CA AUGUST 2-16, 2015 PROGRAM BOOK C ONTENT S For information contact: www.cabrillomusic.org 3 Calendar of Events 831.426.6966 Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary -

Our Noise the Story of Merge Records, the Indie Label That Got Big and Stayed Small 1St Edition Download Free

OUR NOISE THE STORY OF MERGE RECORDS, THE INDIE LABEL THAT GOT BIG AND STAYED SMALL 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John Cook | 9781565126244 | | | | | Merge Records turns 20 To ask other readers questions about Our Noiseplease sign up. Listen to Bowerbirdssome combination of Michigan, Wisconisn and Iowa kidswho understood that Chapel Hill had an established independent bastion before they migrated south. Paperbackpages. Jul 15, Chris Jamieson rated it it was amazing. I do make time to hang out with my friends, because I love them. The inspiring and fun true story of an indie record label that has put out some of my all time favorite records. We operate in a conservative way, Ballance told Reuters from her office in Chapel Hill. The Indie Label That Got Big and Stayed Small 1st edition throughout Tryon Palace were in period costumes and persona, which added to the ambiance and authenticity of the tour. I just want to be a really good role model, and golf is a great way to be an influential figure to young kids. There may even be some American non-profit labels for new artists, but they lay outside of my research. Merge is still putting out first-rate music - take the albums they've released by Destroyer, Caribou and Waxahatachee so far this the Indie Label That Got Big and Stayed Small 1st edition - but both Arcade Fire and Spoon have left the label. From nut clusters and caramels, to dozens of types of truffles and chocolate-dipped strawberries, this shop offers a generous array of options.