MULTIPURPOSE TERMINAL of the PORT of LUANDA Concession of the Seaport Infrastructure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statoil-Environment Impact Study for Block 39

Technical Sheet Title: Environmental Impact Study for the Block 39 Exploratory Drilling Project. Client: Statoil Angola Block 39 AS Belas Business Park, Edifício Luanda 3º e 4º andar, Talatona, Belas Telefone: +244-222 640900; Fax: +244-222 640939. E-mail: [email protected] www.statoil.com Contractor: Holísticos, Lda. – Serviços, Estudos & Consultoria Rua 60, Casa 559, Urbanização Harmonia, Benfica, Luanda Telefone: +244-222 006938; Fax: +244-222 006435. E-mail: [email protected] www.holisticos.co.ao Date: August 2013 Environmental Impact Study for the Block 39 Exploratory Drilling Project TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2. PROJECT SITE .............................................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3. PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE EIS .................................................................................................... 1-5 1.4. AREAS OF INFLUENCE .................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1. Directly Affected area ...................................................................................................... 1-7 1.4.2. Area of direct influence .................................................................................................. -

Angolan Transport Infrastructures

Angolan Transport Infrastructures (Re)Building for the Future Research December 2020 Infrastructure follows pattern of population and natural resources Angola’s population of around 31 million is unequally distributed across the country. Transport Infrastructures The most densely populated areas are around the capital (Luanda) and a few other Tiago Bossa Dionísio major cities (Cabinda, Benguela, Lubango and Huambo). Overall, the coast and the (+351) 964 643 530 southern and eastern parts of the country are less populated than the interior [email protected] highlands. The distribution of the Angolan population results, for the most part, from the devastating impact of the long-lasting civil war period (1975-2002). However, it is also influenced by the presence of vast natural resources and agricultural potential. The interior highlands are abundant in water resources and are, therefore, well suited for agriculture. The south and southeast are dry savanna while the far north is covered by rain forest. Angola’s oil fields are located in the coastal region in the north and west. The country is also rich in various minerals that are found in its western and central parts. Meanwhile, the distribution of infrastructure networks follows the pattern of the population and natural resources. As such, greater density of transport, power and information and communication technology infrastructure is located along the western half of the country. Local authorities have invested heavily in rebuilding infrastructure Angola’s transport infrastructure suffered extensive damage during the civil war period (1975-2002), with destruction and neglect leading to the closure of most of the road and rail networks. -

Angola: Country Profile Report

ANGOLA: COUNTRY PROFILE REPORT 2020-21 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................. 5 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... 6 COUNTRY FACT SHEET ..................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................... 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 10 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ...................................................................... 13 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 13 1.2. Objectives of the Report........................................................................................ 13 1.3. Focus of the Report .............................................................................................. 14 1.4. Methodology ......................................................................................................... 14 1.5. Structure of the Report .......................................................................................... 14 2. OVERVIEW OF ANGOLA -

5.Present Status and Issues of the Target Ports 5-15 5.2 Port of Lobito

THE STUDY ON URGENT REHABILITATION PROGRAM OF PORTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA - FINAL REPORT - 5.Present Status and Issues of the Target Ports 5.2 Port of Lobito 5.2.1 Overview Port of Lobito is located at 30km north of Benguela, in middle area of Angolan coast and physical distribution base in Middle West area utilizing Benguela Railway connecting to inland areas. City of Lobito has about 800 thousand population and the main industries are Benguela Railway, Petroleum, Cement, Brewery, Water and Sewer Company including Lobito Port Authority. The port has been constructed in 1903 by landfill of everglade. The port has the same location pattern as port of Luanda and good natural port. Main handling cargos are daily commodity and restoration related material such as construction material, oil, flour, sugar, grain and general cargo. At this moment, the restoration works of Benguela railways is underway and the port is expected to be important as international hub port for the countries like Zambia, Botswana and Zimbabwe who have no coast and Congo. Figure 5-5 shows the layout of the Port of Lobito and Photo 5-14 shows a panoramic view of the Port of Lobito. Figure 5-5 Present Layout of the Port of Lobito 5-15 THE STUDY ON URGENT REHABILITATION PROGRAM OF PORTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA - FINAL REPORT - 5.Present Status and Issues of the Target Ports Photo 5-14 Panoramic View of the Port of Lobito (2005) 5.2.2 Natural Condition 1) Meteorological Conditions Meteorological information such as temperature, humidity and precipitation for the period from 1991 to 2004 were obtained through the National Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics (INAMET) in Angola. -

Creating Markets in Angola : Country Private Sector Diagnostic

CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA MARKETS IN CREATING COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC SECTOR PRIVATE COUNTRY COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA Opportunities for Development Through the Private Sector COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA Opportunities for Development Through the Private Sector About IFC IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of the world. In fiscal year 2018, we delivered more than $23 billion in long-term financing for developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org © International Finance Corporation 2019. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The findings, interpretations, views, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent. -

NILEDUTCH SERVICES to ANGOLA Penang PORT Colombo KLANG Belawan Pasir Gudang

Aalesund Gaevle Helsinki Stockholm Grangemouth Gothenburg Teesport Helsingborg Belfast Aarhus Liverpool Dublin Copenhagen Cork Felixstowe Gdynia Gdansk Amsterdam Rotterdam ANTWERP Dunkerque Rouen LE HAVRE Strasbourg Genua Beijing Livorno Dalian LEIXOES Barcelona XINGANG-TIANJIN Madrid Istanbul Tokyo Valencia Salerno QINGDAO Inchon Yokohama Nagoya Shimizu Lianyungang LISBON Mersin Busan Osaka Nanjing Hakata SHANGHAI NINGBO Casablanca Haifa Wuhan Wenzhou Chongqing Fuzhou XIAMEN Shantou Keelung Dubai Karachi SHEKOU Taichung Jebel Ali HongKong Kaohsiung Haiphong Mumbai Nhava Sheva Bangkok Manila Chennai Laem Chabang Ho Chi Minh City Cochin Tuticorin NILEDUTCH SERVICES Penang TO ANGOLA PORT Colombo KLANG Belawan Pasir Gudang SINGAPORE CABINDA Jakarta SOYO Semarang Surabaya LUANDA LOBITO NAMIBE PORT OF LUANDA PORT OF LOBITO RIO DE JANEIRO Luanda is the main port of Angola, handling more Lobito used to be the principal port of Angola, partly due to the Benguela railway which SANTOS than 70% of imports and exports of Angola. is currently being rebuilt. The access of the port is easy with the entrance of the bay being about 1.5 mile Johannesburwide. g NileDutch offers direct calls to Lobito on the service ex Europe and ex Asia The port has approx. 2,700 m of berths, divided over 5 terminals: / South Africa. ITAJAI • Multiterminais Ex South America we offer Lobito in transshipment via Luanda. RIO GRANDE • Unicargas • Sogester PORT OF NAMIBE BUENOS AIRES • Sonils Namibe is the 3rd largest port of Angola in terms of movement of cargo. Most cargoes • Soportos destined to the south of the country are discharged at Namibe, transiting to Lubango, NileDutch offers direct calls to Luanda on all our services. -

Rebuilding Angola's Infrastructure

Rebuilding Angola’s Infrastructure Tiago Dionisio ‐ Eaglestone 15/01/2014 Angola has been one of the fastest‐growing economies in the world in the last decade. Thanks to its success as Africa’s second biggest oil exporter, the country’s GDP expanded at an annual 11 per cent and per capita income rose more than eight‐fold during this period. Today, GDP per capita stands above US$5000, which is considered a middle‐income level. Angola’s GDP structure has slowly changed in the last decade. However, the oil and gas sector remains the largest contributor to GDP, accounting for 46 per cent of the total in 2012 (vs. 56 per cent in 2002). It also represents more than 95 per cent of Angola’s exports and 80 per cent of its fiscal revenues. This picture is not likely to change significantly any time soon, but other sectors like mining and agriculture are expected to advance more rapidly in part due to the government’s increased efforts to diversify the economy away from oil. Angolan authorities are focused on implementing a development strategy that will ensure stability, growth and employment in the long‐run. The so‐called “Angola 2025” plan is also targeted at reducing the poverty levels and improving the literacy and skill levels of the local population. A major obstacle for the development of Angola remains the poor quality of its infrastructure, as it significantly hinders the movement of the population and goods in the country. Angola has not only the financial resources and the political will to tackle these issues, but it continues to attract increasing levels of international interest. -

4 Development Directions for Regional Infrastructure

Preparatory Survey for Southern Africa Integrated Transport Program Chapter 4 4 Development Directions for Regional Infrastructure 4.1 Infrastructure Bottlenecks under Growth Scenarios 4.1.1 Current Industrial Situation of the Corridors In parallel with the macro analysis undertaken in Chapter 2, summary information on development potential in the region (especially of mineral resources development accompanied by cross-border transport improvements and an overview of a Mega Project) are presented in this section. More details may be found in Appendix B. The results serve as input to Section 4.1.3 on Infrastructure Bottlenecks under the Growth Scenarios. The figure below visually summarizes the mineral and agricultural potential in the Southern African region. (The number of corridor in Figure 4.1.1 corresponds to this section’s paragraph number.) Figure 4.1.1 Mineral and Agricultural Resources and Corridors (1) Nacala Corridor Nacala is regarded as the best location for a deepwater port on the East African coast. The Nacala Corridor has consequently been at the forefront of ongoing initiatives to rehabilitate the rail link to Malawi, thereby creating a number of “anchor” tenants and promoting development 4-1 Preparatory Survey for Southern Africa Integrated Transport Program Chapter 4 along the corridor. Together with Beira and other corridors (Sena and Tete), these developments have been linked to the possible export of coal from the Moatize and Benga coal fields as well as from the Muchana Vuzi coal fields north of the Cahorra Bassa Dam in Tete Province, Mozambique. The corridor is ultimately seen as linking Lusaka in Zambia with the Port of Nacala. -

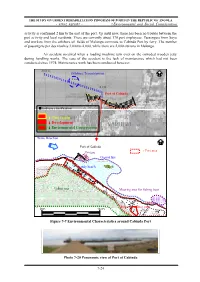

:Concession :Development :Environmental Conservation

THE STUDY ON URGENT REHABILITATION PROGRAM OF PORTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA - FINAL REPORT - 7.Environmental and Social Consideration activity is confirmed 2 km to the east of the port. Up until now, there has been no trouble between the port activity and local residents. There are currently about 170 port employees. Passengers from Soyo and workers from the offshore oil fields of Malongo commute to Cabinda Port by ferry. The number of passengers per day reaches 3,000 to 4,000, while there are 2,000 citizens in Malongo. An accident occurred when a loading machine turn over on the corroded wooden jetty during handling works. The case of the accident is the luck of maintenance which had not been conducted since 1974. Maintenance work has been conducted however. -10.0 m Offshore Transshipment -8.0 m -6.0 m Port of Cabinda ■land-use classification :Concession :Development :Environmental Conservation Wave Direction Port of Cabinda :Port area Dredging Coastal line Existing Shoreline sandy beach Wreck Pavement Port office Urban area Mooring area for fishing boat Empty container yard 0m 1km Existing Container Yard Figure 7-7 Environmental Characteristics around Cabinda Port Photo 7-20 Panoramic view of Port of Cabinda 7-24 THE STUDY ON URGENT REHABILITATION PROGRAM OF PORTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA - FINAL REPORT - 7.Environmental and Social Consideration Photo 7-21 Beach around the jetty Photo 7-22 Dredging work of the basin and the jetty repair work 3) Current environmental issues Table 7-9 Desirable environmental consideration Environmental Issue Desirable environmental consideration Securing the safety of navigation Removal of sunken ships Improvement of charts Installation of navigation aids 7.4 Stakeholders Meeting 7.4.1 Purpose of Stakeholders Meeting Due to the civil war, Angola has not conducted any surveys for water quality, fauna and flora, air, noise and vibration. -

Final Report the Study on Urgent Rehabilitation Program of Ports In

No. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ministry of Transport (MINTRANS) Final Report The Study on Urgent Rehabilitation Program of Ports in the Republic of Angola Main Report August 2006 The Overseas Coastal Area Development Institute of Japan Ecoh Corporation S D J R 06-071 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ministry of Transport (MINTRANS) Final Report The Study on Urgent Rehabilitation Program of Ports in the Republic of Angola Main Report August 2006 The Overseas Coastal Area Development Institute of Japan Ecoh Corporation Exchange Rate (As of October 30, 2005) 1.00 USD = 87.6 Kz = 116 JPY PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of the Republic of Angola (hereinafter referred to as “GOA”), the Government of Japan decided to conduct a Study on Urgent Rehabilitation Program of Ports in the Republic of Angola and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team to Angola four times between March 2005 and August 2006, which was headed by Dr. Haruo Okada and composed of members from the Overseas Coastal Area Development Institute of Japan (OCDI) and Ecoh Corporation. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the GOA and conducted the field surveys at the study area. Upon returning to Japan, the team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this rehabilitation plan and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of GOA for their close cooperation extended to the team. -

Luanda, Angola Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Luanda, Angola Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 LUANDA, ANGOLA ANGOLA Population: 30,355,880 (2018 est.) Population Growth Rate: 3.49% (2018 est.) Median age: 15.9 years GDP: USD$193.6 billion (2017 est.) GDP Per Capita: USD$6,800 (2017 est.) City of Intervention: Luanda Urban Population: 65.5% of total population (2018 est.) Urbanization Rate: 4.32% annual rate of change (2015-20 est.) Land Area: 1,246,700 sq km Total Roadways: 26,000 km (2018) Paved Roadways: 13,600 km (2018) Unpaved Roadways: 12,400 km (2018) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi-Scalar Governance Since its independence in 1975, Angola has been ruled by The People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola. The party was also engaged in a 27-year civil war with political opposition that only ended in 2002. Longtime president Jose Eduardo dos Santos’s chosen successor, Joao Lourenco, was elected in 2017. While Lourenco has changed some of Santos’s old leadership, power remains highly concentrated around the president, with a patronage system extending from the president’s office and often circumventing official channels. Angola has two levels of subnational governments, composed of 18 provinces, 163 municipalities, 376 communes, and 1671 towns. -

15. Future Development of Angolan Ports

THE STUDY ON URGENT REHABILITATION PROGRAM OF PORTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA - FINAL REPORT - 15.Future Development of Angolan Ports 15. Future Development of Angolan Ports 15.1 Requirements for Future Development Angolan economic development has just turned the first corner and its growth will continue for a considerable period of time. International trade grows together with economic development and ports enjoy increasing cargoes. However, ships suffer from long waiting queue; the average waiting time has reached 5-7 days in the first quarter of 2006 at the Port of Luanda. Without a dramatic improvement in cargo handling capacity, ship waiting time will increase rapidly. At the early stage of economic development in China, ship waiting time once reached 30 days and caused serious problems for economic activities. Since Angola imports almost all commodities necessary for daily life, construction, agriculture and manufacturing, it is most important to have capable ports and eliminate ship congestion. Port development is therefore essential to continue economic development and stabilize people's daily life. Requirements for Angolan ports are as follow: (Full Scale Container Terminal) Immediately after the rehabilitation of ports, it will become essential to develop a full scale container terminal. Due to port congestion in the Port of Luanda, surcharges are levied and the freight rates to Angola become much higher than the rates to nearby countries. To reduce the port congestion, development of a new full size modern container terminal is indispensable at the Port of Luanda. The Port of Lobito will also need a full scale container terminal as a gateway to Benguela Railway.