Social Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Values and Resource Use in the Limmen Bight

NATURAL VALUES AND RESOURCE USE IN THE LIMMEN BIGHT REGION © Australian Marine Conservation Society, January 2019 Australian Marine Conservation Society Phone: +61 (07) 3846 6777 Freecall: 1800 066 299 Email: [email protected] PO Box 5815 West End QLD 4101 Keep Top End Coasts Healthy Alliance Keep Top End Coasts Healthy is an alliance of environment groups including the Australian Marine Conservation Society, the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Environment Centre of the Northern Territory. Authors: Chris Smyth and Joel Turner, Centre for Conservation Geography Printing: Printed on 100% recycled paper by IMAGE OFFSET, Darwin. Maps: Centre for Conservation Geography This report is an independent research paper prepared by the Centre for Conservation Geography commissioned by, and for the exclusive use of, the Keep Top End Coasts Healthy (KTECH) alliance. The report must only be used by KTECH, or with the explicit permission of KTECH. The matters covered in the report are those agreed to between KTECH and the authors. The report does not purport to consider exhaustively all values of the Limmen Bight region. The authors do not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation, compensatory, direct, indirect, or consequential damages and claims of third parties that may be caused directly or indirectly through the use of, reliance upon or interpretation of the contents of the report. Cover photos: Main - Limmen River. Photo: David Hancock Inset (L-R): Green Turtle, Recreational fishing is an important leisure activity in -

Vol. 12 • No. 2 • 2018

Vol. 12 • No. 2 • 2018 Published by Umeå University & The Royal Skyttean Society Umeå 2019 The Journal of Northern Studies is published with support from The Royal Skyttean Society and Umeå University © The authors and Journal of Northern Studies ISSN 1654-5915 Cover picture Scandinavia Satellite and sensor: NOAA, AVHRR Level above earth: 840 km Image supplied by METRIA, a division of Lantmateriet, Sweden. www.metria.se NOAAR. cESA/Eurimage 2001. cMetria Satellus 2001 Design and layout Lotta Hortéll and Leena Hortéll, Ord & Co i Umeå AB Fonts: Berling Nova and Futura Printed by Cityprint i Norr AB Contents Editors & Editorial board ...............................................................................................................5 Dag Avango & Peter Sköld, The Making of the European Arctic. Introduction ............7 Articles Dean Carson, Jeanie Govan & Doris Carson, Indigenous Experiences of the Mining Resource Cycle in Australia’s Northern Territory. Benefits, Burdens and Bridges? . 11 Isabelle Brännlund, Diverse Sami Livelihoods. A Comparative Study of Livelihoods in Mountain-Reindeer Husbandry Communities in Swedish Sápmi 1860– 1920. .37 Åsa Össbo, Recurring Colonial Ignorance. A Genealogy of the Swedish Energy System .................................................................................................................................63 Kristina Sehlin MacNeil, Let’s Name It. Identifying Cultural, Structural and Extractive Violence in Indigenous and Extractive Industry Relations ...........81 Miscellanea: Notes -

Aboriginal Interpreter Service

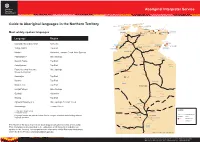

Aboriginal Interpreter Service CROKER ISLAND Guide to Aboriginal languages in the Northern Territory MELVILLE ISLAND Iwaidja GOULBURN ISLANDS BATHURST ISLAND Maung Tiwi ELCHO ISLAND GALIWIN’KU WURRUMIYANGA Ndjebbana MILINGIMBI MANINGRIDA NHULUNBUY DARWIN Burarra Yolngu Matha YIRRKALA Most widely spoken languages GUNBALANYA Kunwinjku RAMINGINING GAPUWIYAK JABIRU Language Region UMBAKUMBA East Side/West Side Kriol Katherine Ngan'gikurrunggurr Nunggubuyu ANGURUGU GROOTE EYLANDT WADEYE East Side Kriol KATHERINE NUMBULWAR Yolngu Matha Top End Anindilyakwa Murrinh Patha NGUKURR West Side Kriol URAPUNGA Warlpiri Katherine, Tennant Creek, Alice Springs HIGHWAY Pitjantjatjara Alice Springs VICTORIA Yanyuwa BORROLOOLA Murrinh Patha Top End Ngarinyman Anindilyakwa Top End Garrwa DAGURAGU Eastern/Central Arrernte, Alice Springs STUART Gurindji Western Arrarnta + KALKARINDJI ELLIOTT Kunwinjku Top End LAJAMANU HIGHWAY Burarra Top End Warumungu Warlpiri BARKLY Modern Tiwi Top End TENNANT CREEK HIGHWAY Luritja/Pintupi Alice Springs Gurindji Katherine ALI CURUNG Alyawarr Maung Top End Alyawarr/Anmatyerr + Alice Springs, Tennant Creek Anmatyerr Warumungu Tennant Creek YUENDUMU Luritja/Pintupi LEGEND Western Desert family PAPUNYA + Arandic family Western Tiwi...................LANGUAGE GROUP Language families are indicated where there is a degree of mutual understanding between Arrarnta ALICE SPRINGS JABIRU .........TOWN language speakers. HERMANNSBURG Eastern/Central Arrernte ELLIOTT ............REMOTE TOWN BARUNGA .........COMMUNITY The Northern Territory -

Local Authority Meeting Agenda

Borroloola Local Authority Meeting Agenda To be held at the Conference Room, Council Services Centre Thursday 11th February 2016 1. Present: 1.1 Elected Members: 1.2 Local Authority Members: 1.3 Staff: 1.4 Visitors/Guests: PLEDGE: “We pledge to work as one towards a better future through effective use of all resources. We have identified these key values and principles of Honesty, Equality, Accountability, Respect, and Trust as being integral in the achievement of our vision that the Roper Gulf Regional Council is Sustainable, Viable and Vibrant”. 2. Apologies: Apologies Accepted Moved: Seconded: 3. Conflict of Interest-Members & Staff: . 4. Minutes of Previous Meeting: Minutes from the previous meeting held on 5th November 2015 pg: 5-9 Motion: That the Borroloola Local Authority accepts the Minutes from the previous Local Authority Meeting held on Thursday 5th November 2015 as a true and accurate record of the meeting. Moved: Seconded: 5. Business Arising/Action List; 5.1. Previous minutes action List Date Item Description Responsible Status Status Comments - Person Completion Date 5.06.2014 LA recommends a Waste DITS Ongoing Action incorporated into Management Strategy is drawn up for RGRC Waste Management the Borroloola region, including Strategy. A newly formed recycling capability and planning for Waste Management Strategy future Committee is driving this Action. * Denotes permanent Agenda items 5.06.2014 LA recommends that Council actively Council Ongoing 10.09.2015-Recommendation: watch & provide information on status Invite NTG Community of housing in Borroloola with regard to Housing & Freehold SIHIP money. Subdivision reps to next LA Mtg for update. -

ROPER GULF REGIONAL COUNCIL Strategic Plan

ROPER GULF REGIONAL COUNCIL Strategic Plan 2018-2021STRATEGIC PLAN 2018-2021 1 ROPER GULF REGIONAL COUNCIL 2018-2021 STRATEGIC PLAN The Roper Gulf Regional Council 2018-2021 Strategic Plan is available online at www.ropergulf.nt.gov.au. For more information about the Strategic Plan, please contact: Manager Governance and Corporate Planning Address: PO Box 1321, Katherine NT 0851 Phone: 08 8972 9005 Email: [email protected] THE LOGO The logo was developed from a concept created by Lainie Joy of Borroloola. The five flowing figures have multiple meanings. They represent the five wards in our region (Never Never, Numbulwar Numburindi, Nyirranggulung, South West Gulf and Yugul Mangi); the five main rivers winding through our Region (the Limmen, McArthur, Robinson, Roper and Rose Rivers); the low-lying hills that are visible on the horizon nearly everywhere in the Roper Gulf Region and the Rainbow Serpent that underlies everything. The colours are based on the different colours of the soil, and the people co-existing in the Roper Gulf region. RGRC ADMINISTRATION CENTRE COUNCIL OFFICES Street Address Phone Fax 2 Crawford Street Katherine NT 0850 Barunga 08 8977 3200 08 8944 7059 Postal Address Beswick 08 8977 2200 08 8975 4565 PO Box 1321 Katherine NT 0851 Borroloola 08 8975 8758 08 8975 8762 Phone 08 8972 9000 Bulman 08 8975 4189 08 8975 4753 Fax 08 8944 7020 Jilkminggan 08 8977 3100 08 8975 4905 Email [email protected] Manyallaluk 08 8975 4055 N/A Website www.ropergulf.nt.gov.au Mataranka 08 8977 2300 08 8975 4608 -

10 Year Infrastructure Plan 2019–2028

ANNUAL REVIEW 10 YEAR INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN 2019–2028 CONTENTS Minister’s Foreword 2 Sectors 16 Northern Territory Cross Sector: Integrated Land Use 16 Economic Environment 3 and Infrastructure Planning Northern Territory Agribusiness, Fisheries and Aquaculture 24 Infrastructure Snapshot 4 Tourism 26 Territory-Wide Logistics Energy and Minerals 36 Master Plan 5 Defence and Related Industries 40 Government’s Infrastructure Focus 6 Education and Training 44 Economic Development Framework 8 Electricity 50 Partnering with the Private Sector 8 Water 54 Onshore Gas Industry Transport and Logistics 60 Development 10 Public Safety and Justice 72 Climate Change 12 Health 78 Development Levers 14 Housing 88 Sectors 15 Art, Culture and Active Recreation 94 Digital 104 Acknowledgements 107 Bibliography 108 How to navigate this document Government initiatives to encourage and support private sector investment are included on pages 8 to 11. Planned and proposed infrastructure projects are provided in each Sector commencing from page 18. The term ‘the Plan’ refers to the 10 Year Infrastructure Plan Annual Review 2019–2028. All statistics referred to in the Plan are based on 2017–18 unless otherwise indicated. Contents I 1 MINISTER’S FOREWORD The Northern Territory provides many opportunities for strategic private sector investment and the Northern Territory Government will support the growth and adaptability of local industry so it is strategically aligned with our growth sectors and global demand. The annual review of the 10 Year Infrastructure Plan This will bridge the gap for local industry to explore provides transparency in planning and prioritises investment diversity opportunities so they can continue projects identified as supporting the future growth and to sustain and grow through changing economic times. -

CW027 2016 Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation Working Paper CW027

Enterprising Pathways: Workshop report Eva McRae-Williams Working paper CW027 2016 Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation Working Paper CW027 ISBN: 978-1-74158-272-7 Citation McRae-Williams E. 2016. Enterprising Pathways: Workshop report. CRC-REP Working Paper CW027. Ninti One Limited, Alice Springs. Acknowledgement The author wishes to acknowledge the following people for their contribution to this research: Steve Blake, Stephanie Hawkins, Karen Lindsay, Morag Dwyer, Indu Balachandran, Kali Balint, Alice Beilby, Mart Motlop, Jude Emmett, Laura Egan, Margaret Duncan, Lillian Tait, Maree Cochrane, Tanya Egerton, Nathaniel Joshua, Sarah Barrow, Jo Fry, Peter Solly, Naomi Bonson, Kim Davis, Katherine Gibson, Eileen Breen, Michelle Evans, Marc Gardner, Helena Lardy, Neil Swan, Mick McCallum, Selena Uibo and Steve Fisher. The Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation receives funding through the Australian Government Cooperative Research Centres Program. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of CRC-REP or its Participants. About the author Based in Darwin, Dr Eva McRae-Williams was the Principal Research Leader for the Pathways to Employment project with the CRC-REP and Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education. Eva’s research interests are in work, employment and livelihood studies; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander studies; and the field of education. For additional information please contact Ninti One Limited Communications Manager PO Box 3971 Alice Springs NT 0871 Australia Telephone +61 8 8959 6000 Fax +61 8 8959 6048 Email: [email protected] www.nintione.com.au The CRC-REP produces two series of reports: working papers and research reports. Working papers describe work in progress for the purposes of reporting back to stakeholders and for generating discussion. -

Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Visions and Violence of Policy An ethnography of Indigenous Affairs bureaucratic reform in the Northern Territory of Australia Thomas Michel Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 1 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. I declare my previously published works are: Michel, T. (2018). The Lifeblood of the Cyborg: Or, the shared organism of a modern energy corporation and a small Northern Territory town. Energy Research & Social Science, 45 (November 2018), 224-234. Michel, T. (2016). Cyborg Wadeye. Arena Magazine, 142, 34-37. Michel, T. (2015). The Special Case of Reform in the Northern Territory: What Are The Lessons? In I. Tiley & B. Dollery (Eds.), Perspectives on Australian Local Government Reform. Sydney: Federation Press. Michel, T., & Bassinder, J. A. (2013). Researching with Reciprocity: Meaningful Participant- Based Research in a Remote Indigenous Community Context. Paper presented at the Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government (ACELG) 3rd National Local Government Researchers' Forum, 6-7 June 2013, University of Adelaide, South Australia. http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ocs/index.php/acelg/PNLGRF/paper/view/478 Michel, T., & Taylor, A. (2012). Death by a thousand grants? The challenge of grant funding reliance for local government councils in the Northern Territory of Australia. -

Regional Plan Was Approved by Council at Its Ordinary Meeting in Katherine on 29 July 2020

ROPER GULF REGIONAL COUNCIL REGIONAL REGIONAL PLAN 2020/21 Council Support Centre WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Street Address Strait Islander readers are advised that 2 Crawford Street Katherine NT 0850 this document may include the images of people who are deceased. Postal Address PO Box 1321 Katherine NT 0851 Phone 08 8972 9000 Fax 08 8911 7020 Email [email protected] Website www.ropergulf.nt.gov.au Roper Gulf Regional Council | ABN 94 746 956 090 The Logo Workshop and Depot 63 Chardon Street Katherine NT 0850 The logo was developed from a concept created by Lainie Joy of Borroloola. Council Offices The five flowing figures have multiple Phone Fax meanings. They represent the five wards Barunga 08 8977 3200 08 8944 7059 in our Region (Never Never, Numbulwar Beswick 08 8977 2200 08 8975 4565 Numburindi, Nyirranggulung, South West Borroloola 08 8975 7700 08 8975 8762 Gulf and Yugul Mangi); the five main Bulman 08 8975 4189 08 8975 4753 rivers winding through our Region (the Jilkminggan 08 8977 3100 08 8975 4905 Limmen, McArthur, Robinson, Roper and Manyallaluk 08 8975 4091 N/A Rose Rivers); the low-lying hills that are Mataranka 08 8977 2300 08 8975 4608 visible on the horizon nearly everywhere in Ngukurr 08 8977 4601 08 8975 4658 the Roper Gulf Region and the Rainbow Serpent that underlies everything. The Numbulwar 08 8977 2101 08 8975 4673 colours are based on the different colours Urapunga 08 8977 4601 N/A of the soil, and the people co-existing in Other Locations the Roper Gulf Region. -

2017-10-31 LGANT Newsletter

For LGANT to lead, represent and be influential for the benefit of local Is this email not displaying correctly? government View it in your browser. November 1... Mayor, President and CEO forum 2... LGANT General Meeting 3... Annual General Meeting A note from our President 7... City of Palmerston 8... West Arnhem Regional Council The Mayors, Presidents and CEO forums 14... City of Darwin followed by the annual general meeting and 15… Belyuen Community general meetings will again take place this Government Council year at the Alice Springs Town Council 21... Wagait Council Chambers on the 1-3 November 2017. The LGANT Executive meeting event will also involve the election of the new Coomalie Community LGANT Executive members from NT councils Government voting for their representatives. Council City of Palmerston The recent 2017 Leadership Symposium at Victoria Daly Regional Council the Rydges Hotel in Palmerston on the 5-6 22... East Arnhem Regional Council October was an outstanding success which Tiwi Islands Regional Council saw many at the leadership level undertake Litchfield Council professional development . The two days West Daly Regional Council consisted of presentations from key note 27... Alice Springs Town Council speakers and a number of workshops around 28... Katherine Town Council leadership such as roles, responsibilities, legislative compliance and meeting City of Darwin procedures. Feedback was extremely positive 30... Central Desert Regional with many council attendees agreeing that Council further training and refresher sessions would benefit both themselves and their fellow December council members. 5… City of Palmerston Many thanks to all the presenters who gave 6… West Arnhem Regional Council informative and practical sessions that were West Arnhem Regional Council most beneficial and engaging. -

Annual Report 2019 Website Facebook Twitter Instagram Visits 27,416 Likes 4,410 Followers 847 Followers 1,499 Artback NT 2019

Section Page 1 Annual Report 2019 Website Facebook Twitter Instagram visits 27,416 likes 4,410 followers 847 followers 1,499 Artback NT 2019 Audience Performances NT 27,501 NT 23 National 44,308 National 5 International 9,142 International 4 Total 80,951 Total 32 Workshops Venue by Location NT 57 NT 78 National 4 National 6 International 6 International 9 Total 67 Total 93 Kilometres travelled: Kilometres travelled: exhibition/event people 83,861 518,269 Artists/arts workers engaged School events NT 745* 49 National 26 Schools visited International 10 Total 781 23 Indigenous artists/ Media activity arts workers (interviews, articles) 730 43 *84% of NT artists and arts workers engaged were from remote or very remote locations throughout the Northern Territory (this figure excludes Darwin, Katherine and Alice Springs). Pirlangimpi (1,1) Wurrumiyanga / Nguiu (Bathurst Island) (9,19) Milikapiti (2,2) Ngaruwanajirri Mudginberri (1,1) Darwin (68,267) Croker Island (1,2) Palmerston (14,39) Bagot (2,3) Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) (5,41) Warruwi (Goulburn Island) (3,30) Howard Springs (2,6) Mandorah (1,2) West Island (1,1) Maningrida (7,36) Girraween (1,2) Belyuen (1,2) Ramingining (4,9) Thursday Island (1,4) ARTBACK NT 2019 Milingimbi (3,8) Bees Creek (1,3) Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island) (4,12) Humpty Doo (2,4) Nhulunbuy (18,46) Noonamah (1,1) Gunyangara (1,1) Berry Springs (1,1) Coomalie (1,1) Yirrkala (7,34) Mapoon (1,1) Batchelor (5,21) Gapuwiyak (2,4) Jabiru (9,45) Garrthalala (1,1) Litchfield (1,2) Cooinda (1,1) Adelaide River (1,6) Bulman (1,2) Andanangki -

Annual Report 2016-2017 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION of the NORTHERN TERRITORY

Annual Report 2016-2017 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Annual Report 2016-2017 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Table of Contents Chief Executive Officer’s Report ..............................................................................................5 President’s Report on Behalf of the Executive .........................................................................7 About this Report .....................................................................................................................9 About the Association ............................................................................................................10 High Level Elements of LGANT’s Strategic Plan....................................................................11 Membership 2016-2017 .........................................................................................................12 Local Government Areas in the Northern Territory as at 30 June 2017 ..................................13 Executive Committee Members 2016-2017............................................................................14 LGANT Organisational Structure as at 30 June 2017.............................................................22 Service Providers and Sponsors ............................................................................................23 Annual Priority Achievements 2016-2017...............................................................................24 Goal 1 – To enhance the status of local