Petitioner Circulator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RI Equisetopsida and Lycopodiopsida.Indd

IIntroductionntroduction byby FFrancisrancis UnderwoodUnderwood Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida and Isoetopsida Special Th anks to the following for giving permission for the use their images. Robbin Moran New York Botanical Garden George Yatskievych and Ann Larson Missouri Botanical Garden Jan De Laet, plantsystematics.org Th is pdf is a companion publication to Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida & Isoetopsida at among-ri-wildfl owers.org Th e Elfi n Press 2016 Introduction Formerly known as fern allies, Horsetails, Club-mosses, Fir-mosses, Spike-mosses and Quillworts are plants that have an alternate generation life-cycle similar to ferns, having both sporophyte and gametophyte stages. Equisetopsida Horsetails date from the Devonian period (416 to 359 million years ago) in earth’s history where they were trees up to 110 feet in height and helped to form the coal deposits of the Carboniferous period. Only one genus has survived to modern times (Equisetum). Horsetails Horsetails (Equisetum) have jointed stems with whorls of thin narrow leaves. In the sporophyte stage, they have a sterile and fertile form. Th ey produce only one type of spore. While the gametophytes produced from the spores appear to be plentiful, the successful reproduction of the sporophyte form is low with most Horsetails reproducing vegetatively. Lycopodiopsida Lycopodiopsida includes the clubmosses (Dendrolycopodium, Diphasiastrum, Lycopodiella, Lycopodium , Spinulum) and Fir-mosses (Huperzia) Clubmosses Clubmosses are evergreen plants that produce only microspores that develop into a gametophyte capable of producing both sperm and egg cells. Club-mosses can produce the spores either in leaf axils or at the top of their stems. Th e spore capsules form in a cone-like structures (strobili) at the top of the plants. -

Methods and Work Profile

REVIEW OF THE KNOWN AND POTENTIAL BIODIVERSITY IMPACTS OF PHYTOPHTHORA AND THE LIKELY IMPACT ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES JANUARY 2011 Simon Conyers Kate Somerwill Carmel Ramwell John Hughes Ruth Laybourn Naomi Jones Food and Environment Research Agency Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 13 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Objectives .......................................................................................................................... 15 2. Review of the potential impacts on species of higher trophic groups .................... 16 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 Methods ............................................................................................................................. 16 2.3 Results ............................................................................................................................... 17 2.4 Discussion .......................................................................................................................... 44 3. Review of the potential impacts on ecosystem services ....................................... -

Notes on Some Species of Diphasiastrum

Preslia, Praha, 47: 232 - 240, 1975 Notes on some species of Diphasiastrum Poznamky k n~kterym druhum rodu Dipha11iaatrum Josef Holub HOLUB J. (1975): Notes on some species of Diphasiastrum. - Preslia, Praha, 47: 232- 240. Taxonomic and nomenclatural problems of some species of Diphasiastrum HOLUB are discussed. A special attention is pa.id to the interspecies D. / X / issleri and D. / x / zei leri. Original plants of D. / x / issleri correspond to the combination D. alpinum - D. complanatum. Plants corresponding to the combination D. alpinum - D. tristachyum have been collected in the ~umava Mts. Some taxa described from the subarctic regions of Europe and North America are shown to belong most probably to the neglected interspecies D. / x / zeileri. Botanical I nstitute, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, 25~ 43 Prithonice, Czecho.,lovakia. INTRODUCTION This is a second part of my study of the new genus Diphasiastrum (HOLUB 1975), which could not be published in this journal in its entirety. Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature are selected from materials gathered originally for my "Catalogue of Czechoslovak vascular plants". With regard to the character of that work the present observations summarize the results of my own studies and suggests problems to be studied in the future. OBSERVATIONS f!.iphasiastrum alpinum (L.) HOLUB Two varieties have been described in this species (both under the name Lycopodium alpi nttm L.): var. thellungii HERTER from Switzerland and var. planiramulosum TAKEDA from Japan. Both these taxa, especially the first one, require a taxonomic revision; the possibility cannot be exclu<led that they are conspecific with D. / x / issleri. -

The Role of Protein O-Mannosyltransferase in The

THE ROLE OF PROTEIN O-MANNOSYLTRANSFERASE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF DROSOPHILA TORSION PHENOTYPES A Dissertation by RYAN ANDREW BAKER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Vladislav Panin Committee Members, Gary Kunkel Lanying Zeng Paul Hardin Head of Department, Gregory Reinhart December 2016 Major Subject: Biochemistry Copyright 2016 Ryan Baker ABSTRACT Congenital muscular dystrophies (CMD’s) are serious diseases affecting muscle, brain, eye, and other tissues and often result in premature death of patients. These forms of muscular dystrophy are largely underlain by defects in the glycosylation of dystroglycan, and specifically by defects in the O-mannosylation pathway. The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is a good model system for studying many genetic diseases, including CMD’s, as they utilize many of the same molecular processes as mammals. They have homologues of mammalian Protein O-MannosylTransferase (POMT) 1 and 2 which have been shown to O-mannosylate dystroglycan. In this dissertation I studied the biological defects associated with POMT mutations primarily by using a live imaging approach in Drosophila. In Drosophila the most prominent defect associated with POMT mutations is a clockwise torsion of posterior abdominal segments relative to anterior segments. The mechanism by which this torsion arises was not previously known. Here I characterized the gross physiological mechanism by which torsion arises. I showed that it is present at the embryonic stage, that embryos undergo chiral rolling within their shells during peristaltic contractions, and that abnormal contraction patterning in POMT mutants leads to differential rolling that gives rise to torsion of the dorsal midline. -

Xyleninae 73.087 2385 Small Mottled Willow

Xyleninae 73.087 2385 Small Mottled Willow (Spodoptera exigua) 73.089 2386 Mediterranean Brocade (Spodoptera littoralis) 73.091 2396 Rosy Marbled (Elaphria venustula) 73.092 2387 Mottled Rustic (Caradrina morpheus) 73.093 2387a Clancy's Rustic (Caradrina kadenii) 73.095 2389 Pale Mottled Willow (Caradrina clavipalpis) 73.096 2381 Uncertain (Hoplodrina octogenaria) 73.0961 2381x Uncertain/Rustic agg. (Hoplodrina octogenaria/blanda) 73.097 2382 Rustic (Hoplodrina blanda) 73.099 2384 Vine's Rustic (Hoplodrina ambigua) 73.100 2391 Silky Wainscot (Chilodes maritima) 73.101 2380 Treble Lines (Charanyca trigrammica) 73.102 2302 Brown Rustic (Rusina ferruginea) 73.103 2392 Marsh Moth (Athetis pallustris) 73.104 2392a Porter's Rustic (Athetis hospes) 73.105 2301 Bird's Wing (Dypterygia scabriuscula) 73.106 2304 Orache Moth (Trachea atriplicis) 73.107 2300 Old Lady (Mormo maura) 73.109 2303 Straw Underwing (Thalpophila matura) 73.111 2097 Purple Cloud (Actinotia polyodon) 73.113 2306 Angle Shades (Phlogophora meticulosa) 73.114 2305 Small Angle Shades (Euplexia lucipara) 73.118 2367 Haworth's Minor (Celaena haworthii) 73.119 2368 Crescent (Helotropha leucostigma) 73.120 2352 Dusky Sallow (Eremobia ochroleuca) 73.121 2364 Frosted Orange (Gortyna flavago) 73.123 2361 Rosy Rustic (Hydraecia micacea) 73.124 2362 Butterbur (Hydraecia petasitis) 73.126 2358 Saltern Ear (Amphipoea fucosa) 73.127 2357 Large Ear (Amphipoea lucens) 73.128 2360 Ear Moth (Amphipoea oculea) 73.1281 2360x Ear Moth agg. (Amphipoea oculea agg.) 73.131 2353 Flounced Rustic (Luperina -

Vulnerability of At-Risk Species to Climate Change in New York (PDF

Vulnerability of At-risk Species to Climate Change in New York Matthew D. Schlesinger, Jeffrey D. Corser, Kelly A. Perkins, and Erin L. White New York Natural Heritage Program A Partnership between The Nature Conservancy and the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation New York Natural Heritage Program i 625 Broadway, 5th Floor Albany, NY 12233-4757 (518) 402-8935 Fax (518) 402-8925 www.nynhp.org Vulnerability of At-risk Species to Climate Change in New York Matthew D. Schlesinger Jeffrey D. Corser Kelly A. Perkins Erin L. White New York Natural Heritage Program 625 Broadway, 5th Floor, Albany, NY 12233-4757 March 2011 Please cite this document as follows: Schlesinger, M.D., J.D. Corser, K.A. Perkins, and E.L. White. 2011. Vulnerability of at-risk species to climate change in New York. New York Natural Heritage Program, Albany, NY. Cover photos: Brook floater (Alismodonta varicosa) by E. Gordon, Spadefoot toad (Scaphiopus holbrookii) by Jesse Jaycox, and Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger) by Steve Young. Climate predictions are from www.climatewizard.org. New York Natural Heritage Program ii Executive summary Vulnerability assessments are rapidly becoming an essential tool in climate change adaptation planning. As states revise their Wildlife Action Plans, the need to integrate climate change considerations drives the adoption of vulnerability assessments as critical components. To help meet this need for New York, we calculated the relative vulnerability of 119 of New York’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) using NatureServe’s Climate Change Vulnerability Index (CCVI). Funding was provided to the New York Natural Heritage Program by New York State Wildlife Grants in cooperation with the U.S. -

Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs

INSECTS THAT FEED ON COLORADO TREES AND SHRUBS1 Whitney Cranshaw David Leatherman Boris Kondratieff Bulletin 506A TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFOLIATORS .................................................... 8 Leaf Feeding Caterpillars .............................................. 8 Cecropia Moth ................................................ 8 Polyphemus Moth ............................................. 9 Nevada Buck Moth ............................................. 9 Pandora Moth ............................................... 10 Io Moth .................................................... 10 Fall Webworm ............................................... 11 Tiger Moth ................................................. 12 American Dagger Moth ......................................... 13 Redhumped Caterpillar ......................................... 13 Achemon Sphinx ............................................. 14 Table 1. Common sphinx moths of Colorado .......................... 14 Douglas-fir Tussock Moth ....................................... 15 1. Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University Cooperative Extension etnomologist and associate professor, entomology; David Leatherman, entomologist, Colorado State Forest Service; Boris Kondratieff, associate professor, entomology. 8/93. ©Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 1994. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension office. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

Mining Index To

MINING INDEX TO HENDERSON, HOLLISTER, AND CANFIELD HISTORIES DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY WESTERN HISTORY DEPARTMENT Typed and edited by Rita Torres February, 1995 MINING INDEX to Henderson, Hollister, and Canfield mining histories. Names of mines, mining companies, mining districts, lodes, veins, claims, and tunnels are indexed with page number. Call numbers are as follows: Henderson, Charles. Mining in Colorado; a history of discovery, development and production. C622.09 H38m Canfield, John. Mines and mining men of Colorado, historical, descriptive and pictorial; an account of the principal producing mines of gold and silver, the bonanza kings and successful prospectors, the picturesque camps and thriving cities of the Rocky Mountain region. C978.86 C162mi Hollister, Orvando. The mines of Colorado. C622.09 H72m A M W Abe Lincoln mine p.155c, 156b, 158a, 159b, p.57b 160b Henderson Henderson Adams & Stahl A M W mill p.230d p.160b Henderson Henderson Adams & Twibell A Y & Minnie p.232b p.23b Henderson Canfield Adams district A Y & Minnie mill p.319 p.42d, 158b, 160b Hollister Henderson Adams mill A Y & Minnie mines p.42d, 157b, 163b,c, 164b p.148a, 149d, 153a,c,d, 156c, Henderson 161d Henderson Adams mine p.43a, 153a, 156b, 158a A Y mine, Leadville Henderson p.42a, 139d, 141d, 147c, 143b, 144b Adams mining co. Henderson p.139c, 141c, 143a Henderson 1 Adelaide smelter Alabama mine p.11a p.49a Henderson Henderson Adelia lode Alamakee mine p.335 p.40b, 105c Hollister Henderson Adeline lode Alaska mine, Poughkeepsie gulch p.211 p.49a, 182c Hollister Henderson Adrian gold mining co. -

Synthesis of Aquatic Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments for the Interior West

FINAL REPORT: SYNTHESIS OF AQUATIC CLIMATE CHANGE VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENTS FOR THE INTERIOR WEST MARCH 31ST, 2015 This report was produced by the Rocky Mountain Research Station as part of the Southern Rockies Landscape Conservation Cooperative project “Vulnerability Assessments: Synthesis and Applications for Aquatic Species and their habitats in the Southern Rockies Landscape Conservation Cooperative”IA#R13PG80650 Report authors: Megan M. Friggens United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Albuquerque, New Mexico Carly K. Woodlief United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Albuquerque, New Mexico For More Information or to request a copy of this report or data, please contact: Megan Friggens Rocky Mountain Research Station 333 Broadway SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 [email protected] Cover: Adapted From Averyt et al. 2013. Sectoral contributions to surface water stress in the coterminous United States. Environmental Research Letters 8: 035046 (9pp). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Vulnerability Assessments ........................................................................................................................ 6 Vulnerability Assessment Approaches ..................................................................................................... -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

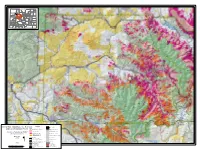

Forest Wide Hazardous Tree Removal and Fuels Reduction Project

107°0'0"W 1 F 8 r H 2 a 2 a 2 0 3 rsh a . s 203 9 .1 Sheephorn Mountain Gu 1 e .1 8.1 lch r A 2 ek Trappers Peak C 0 1 8 4 2 .1 re r 8 C ee 1 m p k 1 20 a . 3 8 C . 9 3 1 . 1 0 M 2 7 M Colorado 8 a iddl 7 rv 3.1 2 Sedgwi1ck e For in k k 8 S e C e 82 5 1 De 18 5 1 r e rby 8. 1 D 1 9 8 1 8 .1 C ree u . k Congor Mesa r n 1 g C Logan y n i n r e ek Battle Mountain d y Jackson Larimer F K Moffat l si Phillips o d pruce C re e e t e 6 r th S k i k r t o e e Weld 2 1 k C N Routt 1 1 f r 8 0 C r r C 5 8 2 . u e Dice Hill 7. 7 1 a e e 1 6 3 b o k 1 8 Project Ao rea Sheep Mountain 6 N i a 2 . .1 5 D 1 1 n e k . 8 R 1 Morgan N C G re 1 3 r C 96 7 e 1 8 ek r . 1 .1 e Grand 30 re l e C Grand Boulder k .1 C il R 1 e - Washington Yuma N . 6 Grand Co. u c M 3 Rio Blanco 1 1 5 1 p r r 8 1 C S k e 8 9 0 P Routt e v 1 1 .