4 Telecoms and Networks 135 5 Internet and Online Content 177 6 Post 217 7 Glossary & Table of Figures 247

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

FOTV-Report-Online-SP.Pdf

A FUTURE FOR PUBLIC SERVICE TELEVISION: CONTENT AND PLATFORMS IN A DIGITAL WORLD A report on the future of public service television in the UK in the 21st century www.futureoftv.org.uk 1 2 Contents Foreword by David Puttnam 4 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Television and public service 14 Chapter 2: Principles of public service for the 21st century 28 Chapter 3: Television in a rapidly changing world: channels, content and platforms 38 Chapter 4: The BBC 50 Chapter 5: Channel 4 66 Chapter 6: ITV and Channel 5 78 Chapter 7: New sources of public service content 90 Chapter 8: TV: a diverse environment? 102 Chapter 9: Nations and regions 114 Chapter 10: Content diversity 128 Chapter 11: Talent development and training 144 Chapter 12: Conclusion and recommendations 152 Appendix 1: Sir David Normington’s proposals for appointing the BBC board 160 Appendix 2: BAFTA members’ survey 164 Appendix 3: Onora O’Neill, ‘Public service broadcasting, public value and public goods’ 172 Appendix 4: Inquiry events 176 Acknowledgements 179 3 Foreword by Lord Puttnam Public service broadcasting is a noble 20th If only the same could be said of much of century concept. Sitting down to write this our national popular press. Our democracy preface just a few days before the most suffers a distorting effect in the form of significant British political event of my mendacious axe-grinding on the part of most lifetime, with no idea of what the result might of the tabloid newspapers. In his brilliant be, there is every temptation to escape into new book, Enough Said, the former director neutral generalities. -

Local Commercial Radio Content

Local commercial radio content Qualitative Research Report Prepared for Ofcom by Kantar Media 1 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1 Executive summary .................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Summary of key findings .......................................................................................................... 5 2 Background and objectives ..................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Research objectives ............................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Research approach and sample ............................................................................................ 11 2.3.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................. 11 2.3.2 Workshop groups: approach and sample ........................................................................... 11 2.3.3 Research flow summary .................................................................................................... -

UP/DOWNLINK, Jaargang 2014, Nummer 5

UP/DOWNLINK, jaargang 2014, nummer 5 Voorafje De vaste lezers van UP/DOWNLINK zullen wel gedacht hebben… waar blijft nummer 5? Hoewel niet aan een maand (mei) gebonden brachten we de vorige nummers toch altijd zo’n beetje in de derde/vierde week uit. Een deel van de redactie was op groot verlof. De andere leden hebben doorgewerkt zodat toch een volwaardig nummer nog net in mei kon uitkomen. De redactie (Hans, Gerard, Rob en Rob). Inhoud (Kanalen)nieuws en wijzigingen .....................................................................................................2 Algemeen ......................................................................................................................................2 Astra 19 oost .................................................................................................................................5 Astra 23 oost .................................................................................................................................5 Astra 28 oost .................................................................................................................................6 Hotbird 13 oost .............................................................................................................................6 Reacties van lezers ..........................................................................................................................7 Weetjes .............................................................................................................................................7 -

The BBC's Use of Spectrum

The BBC’s Efficient and Effective use of Spectrum Review by Deloitte & Touche LLP commissioned by the BBC Trust’s Finance and Strategy Committee BBC’s Trust Response to the Deloitte & Touche LLPValue for Money study It is the responsibility of the BBC Trust,under the As the report acknowledges the BBC’s focus since Royal Charter,to ensure that Value for Money is the launch of Freeview on maximising the reach achieved by the BBC through its spending of the of the service, the robustness of the signal and licence fee. the picture quality has supported the development In order to fulfil this responsibility,the Trust and success of the digital terrestrial television commissions and publishes a series of independent (DTT) platform. Freeview is now established as the Value for Money reviews each year after discussing most popular digital TV platform. its programme with the Comptroller and Auditor This has led to increased demand for capacity General – the head of the National Audit Office as the BBC and other broadcasters develop (NAO).The reviews are undertaken by the NAO aspirations for new services such as high definition or other external agencies. television. Since capacity on the platform is finite, This study,commissioned by the Trust’s Finance the opportunity costs of spectrum use are high. and Strategy Committee on behalf of the Trust and The BBC must now change its focus from building undertaken by Deloitte & Touche LLP (“Deloitte”), the DTT platform to ensuring that it uses its looks at how efficiently and effectively the BBC spectrum capacity as efficiently as possible and uses the spectrum available to it, and provides provides maximum Value for Money to licence insight into the future challenges and opportunities payers.The BBC Executive affirms this position facing the BBC in the use of the spectrum. -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

BBC Script Agreement for Television and Online March 2017

SCRIPT AGREEMENT FOR TELEVISION AND ONLINE Memorandum of an Agreement made on 21st March 2017. Between The British Broadcasting Corporation whose principal office is at Broadcasting House Portland Place London W1A 1AA (the “BBC”, which term shall where the context so permits include the BBC’s assignees and successors in title including without limitation BBC Studios or any successor to BBC Studios, other production entity or co-producer, distributor, licensee or broadcaster) and The Personal Managers’ Association Limited whose registered office is at Summit House, 170 Finchley Road, London NW3 6BP (Company number 00487049) (the “PMA”) and The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain of First Floor 134 Tooley Street London SE1 2TU (the “WGGB”) establishing the minimum terms which shall be offered by the BBC on commissioning a Writer to write a Script for a television or online programme. 1 CONTENTS 1. Application of Agreement 2. Commissioning 3. Rights 4. Format Rights and Characters 5. Extracts 6. Script Payment and Secondary Channel Use 7. Repeat Fees on Primary Channels 8. Commercial Exploitation 9. Collective Administration 10. Miscellaneous Uses 11. Disputes Procedure 12. Regulation 13. Forum 14. Accounting 15. Publicity 16. Rewrites and Acceptance 17. Moral Rights and Alterations 18. Turnaround 19. Long Running Series 20. Credit 21. Copy of Programme 22. Attendance and Expenses 23. Confidentiality 24. Warranties and Indemnity 25. BBC’s Licensees 26. Term and Termination 27. Notices 28. Assignment 29. No Agency Partnership Joint Venture or Employment 30. Variation 31. Value Added Tax 32. Severability 33. Headings 34. Proper Law 35. Nature of the Agreement SCHEDULES 1. -

Initial Draft Ltr V1.Docx

23 January 2014 STUART MCINTOSH Alex Towers Group Director, Competition BBC Trust 180 Great Portland Street London W1W 5QZ Dear Alex, BBC Trust Significance Test – iPlayer catch-up window extension In accordance with the Terms of Reference of 29 October 2013 and the Addition to the Memorandum of Understanding regarding Significance Tests1, this letter sets out Ofcom’s views on the potential impact on others (“others” being providers or potential providers of alternative products and services) of the BBC Executive’s proposed changes to the BBC iPlayer (‘the Proposals’). We provide our views in order to inform the Trust’s decision on the significance of the Proposals. All aspects of the Proposals (including impact on users) are being considered by the Trust Unit and it is the Trust’s decision as to whether the Proposals are considered significant for the purposes of Clause 25 of the BBC’s Framework Agreement. The Proposals include extending the TV and radio catch-up window from seven to 30 days and removing series stacking from TV. Specifically we understand the Proposals are: To extend the TV catch-up window to enable audiences to stream or download BBC programmes for 30 days after they have been first broadcast rather than seven days; To extend the radio catch-up window to enable audiences to stream or DRM download BBC programmes on the Internet for 30 days after they have been first broadcast rather than seven days; and To remove series stacking for TV (that is, the ability for audiences retrospectively to download or stream multiple episodes of TV programmes). -

Resolution No. 118 Authorizing an Agreement with Insite Wireless Group for Distributed Antenna System for the Times Union Center

RESOLUTION NO. 118 AUTHORIZING AN AGREEMENT WITH INSITE WIRELESS GROUP FOR DISTRIBUTED ANTENNA SYSTEM FOR THE TIMES UNION CENTER Introduced: 4/12/17 By Civic Center Committee: WHEREAS, The Department of General Services through the Purchasing Agent issued a Request for Proposals regarding a Distributed Antenna System (DAS) for the Times Union Center, and WHEREAS, Four Proposals were received and representatives of the Department of General Services reviewed said Proposals and recommended awarding the contract to InSite Wireless Group as the lowest responsible bidder, and WHEREAS, The Commissioner of the Department of General Services indicated that the Times Union Center and Albany Capital Center will split the projected revenues of $500,000 over a ten year period, guaranteed by InSite Wireless Group with the Times Union Center will retain seventy-five percent of revenues and the Albany Capital Center will retain twenty-five percent of revenues collected and paid by InSite Wireless Group, and WHEREAS, The Commissioner of the Department of General Services has proposed to enter into an agreement with InSite Wireless Group for the DAS project to combine services at the Times Union Center and the Albany Capital Center with InSite Wireless Group is responsible for funding of the project, now, therefore be it RESOLVED, By the Albany County Legislature that the County Executive is authorized to enter into an agreement with InSite Wireless Group regarding a Distributed Antenna System, in collaboration with the Times Union Center and Albany Capital Center for a term commencing May 1, 2017 and ending April 30, 2027, and, be it further RESOLVED, That the County Attorney is authorized to approve said agreement as to form and content, and, be it further RESOLVED, That the Clerk of the County Legislature is directed to forward certified copies of this resolution to the appropriate County Officials. -

Owner's Guide

English Deutsch Owner’s Guide v1.0 Français Italiano TECHNICAL SUPPORT WARRANTY Should you encounter problems using this product, please refer to the Revo Technologies Ltd warrants to the end user that this product will troubleshooting section on page 38 of this owner’s guide. be free from defects in materials and workmanship in the course of Alternatively, call Revo technical support on : normal use for a period of one year from the date of purchase. This guarantee covers breakdowns due to manufacturing faults and UK 01555 666161 does not apply in cases such as accidental damage, general wear From outside the UK + 44 1555 666161 and tear, user negligence, modifi cation or repair not authorised by Revo Technologies Ltd. Alternatively, e-mail [email protected] or visit the troubleshooting To register your purchase please visit www.revo.co.uk/register section of our website at: www.revo.co.uk/support ENVIRONMENTAL INFO COPYRIGHTS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PRODUCT DISPOSAL INSTRUCTIONS (WEEE DIRECTIVE) Copyright 2013 Revo Technologies Ltd. All rights reserved. The symbol shown here and on the product means that it is classed as Electrical or Electronic Equipment and should not be disposed with No part of this publication may be copied, distributed, transmitted or other household or commercial waste at the end of its working life. transcribed without the permission of Revo Technologies Limited. The Waste of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive REVO and SUPERCONNECT and are trademarks or registered (2002/96/EC) has been put in place to recycle products using best trademarks of Revo Technologies Ltd. -

FTSE Factsheet

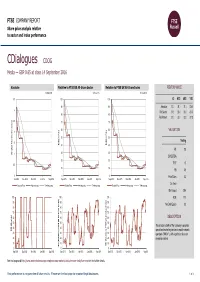

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance Data as at: 14 September 2016 CDialogues CDOG Media — GBP 0.65 at close 14 September 2016 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 14-Sep-2016 14-Sep-2016 14-Sep-2016 3.5 100 100 1D WTD MTD YTD 90 90 Absolute 31.3 31.3 31.3 -23.5 3 Rel.Sector 31.5 33.0 33.2 -24.0 80 80 Rel.Market 31.2 33.3 33.2 -27.8 2.5 70 70 60 60 VALUATION 2 (local currency) (local 50 50 Trailing 1.5 Relative Price 40 Relative Price 40 PE 2.8 30 30 Absolute Price Price Absolute 1 EV/EBITDA - 20 20 0.5 PCF 1.0 10 10 PB 0.5 0 0 0 Price/Sales 0.3 Sep-2015 Dec-2015 Mar-2016 Jun-2016 Sep-2016 Sep-2015 Dec-2015 Mar-2016 Jun-2016 Sep-2016 Sep-2015 Dec-2015 Mar-2016 Jun-2016 Sep-2016 Div Yield - Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Div Payout 29.4 100 100 100 ROE 17.7 90 90 90 Net Debt/Equity 0.0 80 80 80 70 70 70 60 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 The principal activity of the Company is provides 40 40 40 RSI (Absolute) RSI specialised marketing services to mobile network 30 30 30 operators ("MNOs" ), with a particular focus on 20 20 20 emerging markets. -

Media Nations: Wales 2019

Media nations: Wales 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations: Wales report. The report reviews key trends in the television and audio-visual sector as well as the radio and audio industry in Wales. It provides context to the work Ofcom undertakes in furthering the interests of consumers and citizens in the markets we regulate. In addition to this Wales report, there are separate reports for the UK as a whole, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, as well as an interactive data report. The report provides updates on several datasets, including bespoke data collected directly from licensed television and radio broadcasters (for output, spend and revenue in 2018), Ofcom’s proprietary consumer research (for audience opinions), and BARB and RAJAR (for audience consumption). It should be noted that our regulatory powers do not permit us to collect data directly from online video-on-demand and video-sharing services (such as ITV Player, Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and YouTube) for research purposes, and therefore we also use third-party sources for information relating to these services. 1 Contents Overview............................................................................................................ 2 Key points .......................................................................................................... 3 TV services and devices...................................................................................... 5 Screen viewing ..................................................................................................