1 Korngold and the Studio System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazzletter PO Box 240, Ojai CA 93024-0240

Gene Lees - Jazzletter PO Box 240, Ojai CA 93024-0240 Vol. 19 No. 10 October 2000 back in those early New York days. Never did read Constant Mail Bag Lambeit’s book, though I used to see it on library shelves. Pleasants stirred me so with his argtmients that I would ofien, Thank you, thank you! That was like getting permission to even in recent years, grab the book just to read certain, take off a pair of shoes that pinch. chapters’ and get fired up again. You lay it out splendidly, I always wondered what I lacked when others seemed to show correlating ideas about modem art, and then top it off comprehend so much in serial music. Same with modern by demonstrating how Pleasants himselfwas taken in by the dance, with certain exceptions. And, married to a figurative jazz mongers, just as we were bilked by the Serious Music painter for twenty-one years, I saw first-hand the pain felt by hucksters. It was depressing and infuriating to learn how the one who truly tried to create an ordered and empathetic New York Times dealt with his obit. Made him look like a world within the deep space of his own canvas, only to be Moe Berg type. dismissed as unimportant by those who venerated the Thanks for telling me about Schoenberg and the prevail- accidental. - ing attitudes about him and that kind of music. It validates The original Second City troupe in Chicago had a skit in my instincts. The notion that music “progresses” has always which a noted broadcaster-critic-artist was explaining some bothered me. -

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

Die Tote Stadt

Portrait Georges Rodenbach von Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer (1895). Die tote • Die Hauptpersonen Stadt • Paul – Marie – Marietta • Aufführungsgeschichte, Fotos • Fakten • Rodenbachs Roman und Drama • Genesis – Illustrationen – Bedeutung – Textauszug • Korngolds Oper • Korngolds Selbstzeugnis – Genesis – Handlung • Psychologie • Musik • Nähe zu Mahler – Gesangspartien – musikalisches Material – Instrumentation • Videobeispiele © Dr. Sabine Sonntag Hannover, 17. Juni 2011 DIE HAUPTPERSONEN Paul Die verstorbene Marie Die Tänzerin Marietta Die Hauptdarstellerin Brügge Die Hauptdarstellerin Brügge Une Ville Abandonnée von Fernand Khnopff (1904) AUFFÜHRNGSGESCHICHTE FOTOS Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 1967: Wien • 1975: New York City Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 5. Februar 1983, Deutsche Oper Berlin Götz Friedrich, Anmoderation der Sendung von Die tote Stadt, ARD Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 1985: Wien • 1988: Düsseldorf • 1991: New York City • 1990: Niederl. Radio • 1993: Amsterdam • 1995: Ulm • 1996: Catania Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 1997: Spoleto, Wiesbaden • 1998: Washington • 1999: Bremerhaven, Köln • 2000: Karlsruhe • 2001: Straßburg • 2002: Bremen, Gera • 2003: Braunschweig, Zürich, Stockholm Aufführungen Die tote Stadt • 2004: Berlin, Salzburg • 2005: Osnabrück • 2006: Genf, Barcelona, New York City • 2007: Hagen • 2008: Bonn • 2009: Nürnberg, Venedig • 2010: Bern, Helsinki, Regensburg London 2009 Berlin, Deutsche Oper, 2004 Frankfurt 2011 Gelsenkirchen 2010 Madrid 2010 New York 1975 Nürnberg 2010 Palermo 1996 Regensburg 2011 San Francisco 2008 Helsinki 2010 Die Wiederentdeckung 1983 Berlin, Deutsche Oper 1983 FAKTEN • Text von Paul Schott alias Julius Korngold, Erich Wolfgang Korngolds Vater. • UA am 4. Dezember 1920 gleichzeitig im Stadttheater Hamburg (Dirigent: Egon Pollack) sowie im Stadttheater Köln (Dirigent: Otto Klemperer) • 1921 Wien, 1921 Met (Met-Debut von Maria Jeritza) • Das Libretto basiert auf dem symbolistischen Roman Das tote Brügge Bruges-la-morte, 1892; dt. -

Die Tote Stadt Op

Die tote Stadt op. 12 Oper in drei Bildern Frei nach Georges Rodenbachs Roman Bruges-la-morte von Paul Schott Musik von Erich Wolfgang Korngold pERSONEN Paul Tenor Marietta, Tänzerin Sopran Die Erschienung Mariens , pauls verstorbener Gattin } Frank, pauls Freund Bariton Brigitta, bei paul Alt Juliette, Tänzerin Sopran Lucienne, Tänzerin in Mezzosopran Gaston, Tänzer mariettas Mimikerrolle Victorin, der Regisseur Truppe Tenor Fritz, der pierrot } Bariton Graf Albert Tenor Beghinen, die Erscheinung der prozession, Tänzer und Tänzerinnen. Die handlung spielt in Brügge, Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts; die Vorgänge der Vision (II. und zum Teil III. Bild) sind mehrere Wochen später nach jenen des I. Bildes zu denken. La città morta op. 12 Opera in tre quadri Libero adattamento del romanzo Bruges-la-morte di Georges Rodenbach, di Paul Schott Traduzione italiana di Anna Maria Morazzoni (© 2009)* Musica di Erich Wolfgang Korngold pERSONAGGI Paul Tenore Marietta, ballerina Soprano L’apparizione di Marie , defunta moglie di paul } Frank, amico di paul Baritono Brigitta, governante di paul Contralto Juliette, ballerina Soprano Lucienne, ballerina della Mezzosoprano Gaston, ballerino compagnia Mimo Victorin, il regista di marietta Tenore Fritz, il pierrot } Baritono Il conte Albert Tenore Beghine, l’apparizione della processione, ballerini e ballerine. L’azione si svolge a Bruges, alla fine del secolo XIX; gli avvenimenti della visione (Quadro II e parte del III) vanno pensati diverse settimane dopo quelli del Quadro I. Prima rappresentazione assoluta: Amburgo, Stadttheater, 4 dicembre 1920 * per gentile concessione del Teatro La Fenice di Venezia. La traduzione tiene conto anche della versione di Laureto Rodoni ( www.scrivi.com ); alcune scelte lessicali sono desunte dalle varie versioni italiane del romanzo. -

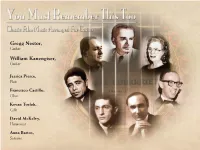

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

1 Filmmuziekmagazine Ennio Morricone

FILMMUZIEKMAGAZINE ENNIO MORRICONE - Eindelijk NUMMER 186 – 45ste JAARGANG – MAART 2016 1 Score 186 Maart 2016 45ste jaargang ISSN-nummer: 0921- 2612 Het e-zine Score is een uitgave van de stichting FILMMUZIEKMAGAZINE Cinemusica, het Nederlands Centrum voor Filmmuziek REDACTIONEEL Informatienummer: ste +31 050-5251991 Vorige week werden voor de 88 keer de Oscars uitgereikt. Het werd een gedenkwaardige editie omdat onder de vijf kan- E-mail: didaten twee oudgedienden uit de rijke wereld van de filmmu- [email protected] ziek tegen elkaar in het strijdperk traden: John Williams ver- sus Ennio Morricone. De laatste won en kan zich nu ook scharen onder een lange reeks winnaars van deze volgens Kernredactie: Paul velen nog steeds belangrijkste filmprijs ter wereld. Over de Stevelmans en Sijbold score waarmee de Maestro dan eindelijk een Oscar won, leest Tonkens u helemaal aan het einde van deze nieuwe editie van Score. Aan Score 186 werkten Een Oscar winnende score van Morricone is een gebeurtenis mee: Paul Stevelmans, waarbij flink wordt uitgepakt. Sijbold Tonkens en Julius Wolthuis Wat velen in Nederland niet weten is dat ooit, in een grijs verleden - om precies te zijn vlak vóór de donkere bezet- tingsjaren - een van oorsprong Nederlandse filmcomponist Eindredactie: Paul een Oscar won als beste filmcomponist van het jaar. Score Stevelmans was aanwezig bij de onthulling van een plaquette voor deze vergeten componist in zijn geboorteplaats Leeuwarden. In een portret over deze Richard Hageman komt u meer te weten Vormgeving: Paul over een componist die een rijk leven heeft geleid. Stevelmans Met dank aan: AMPAS, Alex Simu INHOUDSOPGAVE 3 Oscar 2016: Dat oude mannetje 9 Richard Hageman - Portret 13 Interview met Alex Simu 16 Georges Delerue versus Disney 18 Boekbespreking 19 Recensies 2 OSCAR 2016 DAT OUDE MANNETJE En daar zaten ze weer in die zijloge van het Dolby Theatre in Hollywood: de genomineerde filmcomponisten en hun entourage. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

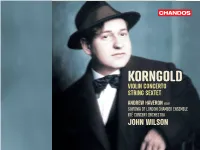

Korngold Violin Concerto String Sextet

KORNGOLD VIOLIN CONCERTO STRING SEXTET ANDREW HAVERON VIOLIN SINFONIA OF LONDON CHAMBER ENSEMBLE RTÉ CONCERT ORCHESTRA JOHN WILSON The Brendan G. Carroll Collection Erich Wolfgang Korngold, 1914, aged seventeen Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) Violin Concerto, Op. 35 (1937, revised 1945)* 24:48 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Dedicated to Alma Mahler-Werfel 1 I Moderato nobile – Poco più mosso – Meno – Meno mosso, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Poco meno – Tempo I – [Cadenza] – Pesante / Ritenuto – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Meno, cantabile – Più – Più – Tempo I – Meno – Più mosso 9:00 2 II Romanze. Andante – Meno – Poco meno – Mosso – Poco meno (misterioso) – Avanti! – Tranquillo – Molto cantabile – Poco meno – Tranquillo (poco meno) – Più mosso – Adagio 8:29 3 III Finale. Allegro assai vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco meno (maestoso) – Fließend – Più tranquillo – Più mosso. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco meno 7:13 String Sextet, Op. 10 (1914 – 16)† 31:31 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur Herrn Präsidenten Dr. Carl Ritter von Wiener gewidmet 3 4 I Tempo I. Moderato (mäßige ) – Tempo II (ruhig fließende – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III. Allegro – Tempo II – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Tempo II – Allmählich fließender – Tempo III – Wieder Tempo II – Tempo III – Drängend – Tempo I – Tempo III – Subito Tempo I (Doppelt so langsam) – Allmählich fließender werdend – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo I – Tempo II (fließend) – Festes Zeitmaß – Tempo III – Ruhigere (Tempo II) – Etwas rascher (Tempo III) – Sehr breit – Tempo II – Subito Tempo III 9:50 5 II Adagio. Langsam – Etwas bewegter – Steigernd – Steigernd – Wieder nachlassend – Drängend – Steigernd – Sehr langsam – Noch ruhiger – Langsam steigernd – Etwas bewegter – Langsam – Sehr breit 8:27 6 III Intermezzo. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere