Bias Theories Contributing to the Enduring Negative Perceptions of Greenspoint, a Rebounding Houston Neighborhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

Conroe, Texas

Conroe, Texas Outlets at Conroe is undergoing a complete redevelopment amidst the enormous growth occurring in and around the City of Conroe. With the influx of corporate offices and master-planned communities, the North Houston area will become the workplace and home to tens of thousands of people in the next few years. The new Outlets at Conroe will be poised to deliver top outlet brands and a wide variety of dining options in a family-friendly environment for this growing constituency. Outlets at Conroe will ultimately be comprised of 340,000 square feet of retail and restaurants. The immediate area already boasts nearly 185,000 cars per day, and is just 30 minutes from George W. Bush International Airport and 50 miles from Houston. LOCATION SHOPPING CENTERS WITHIN 50 MILES OF Conroe, Texas OUTLETS AT CONROE I-45, at exit 90, approximately 50 miles north AERIAL DRIVING DISTANCE of downtown Houston. DISTANCE APPROX. DRIVE TIME A. Teas Crossing, Conroe .79 Mile 2 Miles MARKET JCPenney 2 Minutes Houston B. Conroe Marketplace, Conroe 1 Mile 2 Miles Kohl’s Ross Dress for Less 2 Minutes Shoe Carnival T.J. Maxx C. Market Street, The Woodlands 14 Miles 14 Miles Brooks Brothers The Cinemark at Market Street Theatre 18 Minutes J. Crew kate spade new york Tiffany & Co. Tommy Bahama D. The Woodlands Mall, The Woodlands 14 Miles 14 Miles Dillard’s JCPenney 18 Minutes Macy’s Nordstrom E. Deerbrook Mall, Humble 27 Miles 42 Miles Dillard’s JCPenney 48 Minutes Macy’s F. Willowbrook Mall, Houston 28 Miles 40 Miles Dillard’s JCPenney 48 Minutes Macy’s Nordstrom Rack G. -

Almeda Macy's Stays

4040 yearsyears ofof coveringcovering SSouthouth BBeltelt Voice of Community-Minded People since 1976 Thursday, January 12, 2017 Email: [email protected] www.southbeltleader.com Vol. 41, No. 49 Dobie parent meeting set Dobie High School will hold a parent night Thursday, Jan. 12, in the auditorium at 6:30 p.m. for incoming freshmen for the 2017-2018 Almeda Macy’s stays; Pasadena goes school year. School offi cials say they cannot ex- nate more than 10,000 jobs – 3,900 directly re- is pleased with the announcement. press enough the importance of this meeting, as By James Bolen tive or are no longer robust shopping destina- The Macy’s Almeda Mall location was spared tions due to changes in the local retail shopping lated to the closures and an additional 6,200 due “We are delighted the Macy’s list has been they will share important course registration in- to company restructuring. published, and as we expected, the Almeda formation with parents and students before they closure this past week when the retail giant an- landscape,” Macy’s CEO Terry Lundgren said in nounced the sites of 68 stores it plans to close a statement. Opened in 1962, the 209,000-squre-foot Pasa- Macy’s is not part of the nationwide store clos- register for classes for the upcoming school dena Town Square Macy’s will account for 78 ings,” Felton said. “Macy’s has always shown year. There will be an update on the new fresh- this year in an effort to cut costs amid lower The announcement came fresh on the heels sales. -

Component Units

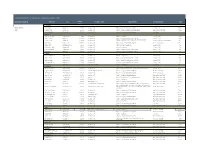

2015 – 2019 Capital Improvement Plan City of Houston Component Units Component Units (Governmental and Business-Type) are legally separate organizations for which elected officials of the City of Houston are financially accountable or the nature and significance of the relationship is such that exclusion would cause financial statements to be misleading or incomplete. Therefore, theses component units should be included in the City’s 5 year Capital Improvement Plan. Governmental type units provide services largely through non-exchange revenues (taxes are the most common example) and includes primarily boards and redevelopment authorities. Business-type units are financed and operated in a manner similar to private business enterprise where the cost of providing goods or services to the general public is financed primarily through user charges. 1 2015 – 2019 Capital Improvement Plan City of Houston Table of Component Units Unit Has CIP? CIP as Of: Governmental Type City Park Redevelopment Authority N East Downtown Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Fifth Ward Redevelopment Authority N Fourth Ward Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Greater Greenspoint Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Bureau N Gulfgate Redevelopment Authority N Hardy Near Northside Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 HALAN – Houston Area Library Automated Network Board N Houston Arts Alliance N Houston Downtown Park Corporation N Houston Forensic Science LGC, Inc. N Houston Media Source N Houston Parks Board, Inc. Y FY15-19 Houston Parks Board LGC., Inc. N Houston Public Library Foundation N Houston Recovery Center LGC N Lamar Terrace Public Improvement District N Land Assemblage Redevelopment Authority N Leland Woods Redevelopment Authority N Leland Woods Redevelopment Authority II N Main Street Market Square Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Memorial City Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Memorial-Heights Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Midtown Redevelopment Authority Y FY14-18 Miller Theatre Advisory Board, Inc. -

Houston Distribution

MAP Houston P: 713.942-7676 AJR Media Group F: 713.942-0277 E: [email protected] Web: www.AJRMediaGroup.com www.mapamerica.com THE RIGHT DIRECTION. ® HOUSTON DISTRIBUTION AIRPORT / 11.6% 88,000 AmeriSuites - Hobby 800 Comfort Suites - Clay Road 800 Econo Lodge - Med Center 1,200 Bush Intercontinental Airport 62,000 AmeriSuites - InterContAirport 800 Comfort Suites - Deer Park 800 Econo Lodge - Northwest 1,200 Hobby Airport 26,000 Baymont 800 Comfort Suites - Intercontinental 1,200 Embassy Suites - Galleria 1,600 Baymont - N.W. Frwy 800 Comfort Suites - Katy Freeway 800 Embassy Suites - SW Freeway 400 APARTMENTS / 0.1% 950 Baymont Inn & Suites - Baytown 800 Comfort Suites - Kingwood 800 Executive Inn & Suites - NW Frwy. 800 Post Midtown Square 150 Baymont Inn & Suites - Conroe 800 Comfort Suites - Overland 400 Extended StayAmerica - Post Rice Lofts 800 Baymont Inn & Suites - Comfort Suites - Reliant Park 2,000 Braeswood 800 SW Freeway 800 Comfort Suites - Richmond Ave. 1,200 Extended StayAmerica - ATTRACTIONS / Best Value Budget Inn - Comfort Suites - Shenandoah 800 Champions Ctn 800 MUSEUMS / 2.3% 17,800 Channelview 800 Comfort Suites - Spring 400 Extended StayAmerica - Galleria 800 Children's Museum - Group Dept. 200 Best Value Inn - Baytown 800 Comfort Suites - Stafford 800 Extended StayAmerica - Galveston Railroad Museum 400 Best Value Inn&Suites - Texas City 800 Comfort Suites - Willowbrook 800 Guhn Road 800 Gulf Grayhound Race Track 800 Best Value Platinum Inn&Swts 800 Commodore Hotel 800 Extended StayAmerica - Hollister 800 Health Museum 400 Best Western - Baytown Inn 800 Corporate Inn - Conroe 400 Extended StayAmerica - I 45 N 800 Holocaust Museum 2,000 Best Western - Deer Park Inn&Swts 800 Country Inn & Suites - Extended StayAmerica - Katy Frwy 800 Houston Arboretum 800 Best Western - FM 1960 400 Intercontinental 800 Extended StayAmerica - La Concha 800 Houston Zoo 1,200 Best Western - Galleria 1,600 Country Inn & Suites - JFK Blvd. -

Project Plan and Reinvestment Zone Financing Plan for Reinvestment Zone Number Eleven

• • City of Houston, Te:X3s, Ordinance No. 1999---,---,--,= AN ORDINANCE APPROVING THE PROJECT PLAN AND REINVESTMENT ZONE FINANCING PLAN FOR REINVESTMENT ZONE NUMBER ELEVEN. CITY OF HOUSTON, TEXAS (GREENSPOINT); AUTHORIZING THE CITY SECRETARY TO DISTRffiUTE SUCH PLANS; CONTAINING VARIOUS PROVISIONS RELATED TO THE FOREGOING SUBJECT; AND DECLARING AN EMERGENCY. * * * * * * * \VHEREAS, by City of Houston Ordinance No. 98-713, adopted August 26,1998, the City created Reinvestment Zone Number Eleven, City of Houston, Texas (the "Greenspoint Zone") for the purposes of development within the Greater Greenspoint area of the City; and WHEREAS, the Board of Directors of the Greenspoint Zone has approved the Project Plan and Reinvestment Zone Financing Plan attached hereto for the development of the Greenspoint Zone; and WHEREAS, the City Council must approve the Project Plan and Reinvestment Zone Financing Plan; NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COCNCIL OF THE CITY OF HOUSTON, TEXAS: Section 1. That the findings in the Ordinance are declared to be true correct and are Section 2. That the Plan hereto Zone City Houston. are detennined to feasible are • • Section 3. That the City Secretary is directed to provide copies of the Project Plan and Reinvestment Zone Financing Plan to each taxing unit levying ad valorem taxes in the Greenspoinl Zone. Section 4. That City Council officially finds, determines, recites and declares a sufficient written notice of the date, hour, place and subject of this meeting of the City Council was posted at a place convenient to the public at the City Hall of the City for the time required by law preceding this meeting, as required by the Open Meetings Law, Chapter 551, Texas Government Code, and that this meeting has been open to the public as required by law at all times during which this ordinance and the subject matter thereof has been discussed, considered and formally acted upon. -

Globalization, Obsolescence, Migration and The

BORDERLAND APPROPRIATIONS: GLOBALIZATION, OBSOLESCENCE, MIGRATION AND THE AMERICAN SHOPPING MALL A Dissertation by GREGORY N. MARINIC Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Sarah Deyong Co-chair of Committee, Peter Lang Committee Members, Koichiro Aitani Cecilia Giusti Head of Department, Robert Warden August 2017 Major Subject: Architecture Copyright 2017 Gregory Marinic ABSTRACT The notion of place embodies a complex intersection of architecture, occupancy, and identity. Tied to geographic and historical conditions, built environments existing between two worlds or within contested territories reveal the underlying political and social forces that have shaped them. Assuming an analogous relationship between consumption and architecture as interconnected systems, this dissertation examines American suburbia in the early twenty-first century to assess convergent flows related to consumption. It engages with the changing nature of retail form, function, and obsolescence to illustrate transnational and technological influences impacting suburban commercial architecture. More specifically, it analyzes occupancies, appropriations, and informal adaptations of retail environments in two distinct regional contexts in North America—the USA-Mexico Borderlands of Texas and the USA-Canada Borderlands of the Eastern Great Lakes region. This research charts the rise, fall, and transformation of the American -

Metrolift Designated Stops at Major Locations SCHOOLS MEDICAL

METROLift Designated Stops at Major Locations At frequently visited public places (i.e., schools, shopping centers and hospitals) with multiple entrances, METROLift, together with the property management, has installed designated METROLift stop signs where patrons and drivers can meet. Be sure you’re at the METROLift sign so the driver can see you. This practice helps our drivers to locate all patrons at that stop, making sure that no one is left behind. Below is a list of designated stops at major locations. SCHOOLS University Center for Students with Disabilities Art Institute 4300 Wheeler - Entrance 6 4140 Southwest Freeway - Rear Entrance University of Houston/Downtown Houston Community College (HCC) 2 Travis - Lower Level Parking Garage 3400 Caroline - Jew Don Boney By Police Station - Under Main St. Bridge On Holman at Caroline - Eastbound Business Career Center MEDICAL FACILITIES/HOSPITALS 1301 Alabama - Faculty Parking Ben Taub Lot at Caroline 1502 Taub Loop - Front Entrance Texas Southern University Diagnostic Clinic 4500 Ennis at Wheeler 6448 Main - Front Entrance Athletic Bldg. Under Canopy Hermann Professional Building 3443 Blodgett - by Police Station 6410 Fannin - University of Houston/Central Campus METROLift Entrance - Truck Zone 4800 Calhoun - Entrance 1 Memorial Hermann Hospital 4800 Cullen - Entrance 14 - Ed. Center Melcher Hall 6411 Fannin - Emergency Entrance University Center Houston Northwest Medical Center 4800 Cullen - Entrance 11 710 Judiwood - Front Entrance 20 LBJ Hospital Christus St. Joseph Hospital 5600 Kelley - Front Entrance 1819 LaBranch - Side Entrance M.D. Anderson Hospital/Clinic Christus St. Joseph Cullen 1515 Holcombe - Front Entrance Family Bldg. Medical Towers 1404 St. Joseph Pkwy - Front Entrance 1709 Dryden - Dryden Entrance St. -

Foley’S Furniture, Bedding and Area Rugs Integration to Macy’S Home Store

Foley’s Furniture, Bedding and Area Rugs Integration to Macy’s Home Store March 28, 2006 Dear Home Store Vendor: We appreciate and thank you for your support as we move forward with the Federated-May integration. As outlined in previous communications, the conversion of the Foley’s stores to Macy’s Home Store will occur on July 2, 2006. A store listing and a distribution center listing are attached for your reference. Please keep in mind that each purchase order is your guide as to where and how you are to ship that merchandise. Your inbound EDI ASN (856) and invoice (810) must be sent to the corresponding mailbox from which the original EDI PO (850) was generated. Shipment cut-off dates will be communicated at a later date. Attached is a list of the former Foley’s locations with the new Macy’s Home Store location numbers and distribution centers. Please forward to appropriate parties within your organization. A help desk has been created at 513-782-1412, to answer any questions you have regarding the Federated-May integration. Please make note of the number and provide it to any necessary parties in your organization. Continue to monitor FDSNET (www.fdsnet.com) for any new information on the Federated-May merger. Foley's to Macy's Home Store FURNITURE, BEDDING & AREA RUGS Store/DC List Current Current New * DC Name ** DC Mall Name/ Store Name Address City State Zip Integration Name Store Macy's Alpha Date Plate Number Home Code Store Number FOLEYS 1 7201 Houston HF NorthPark 8687 North Central Expressway Dallas TX 75225 7/2/2006 FOLEYS 3 7226 Houston HF Lakeline 11250 Lake Stop Blvd. -

Cypress, Texas

CYPRESS, TEXAS PROPERTY OVERVIEW HOUSTON PREMIUM OUTLETS® CYPRESS, TX MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS SELECT TENANTS Tollway completed to I-45 Houston: 30 miles Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5TH, Ann Taylor Factory Store, Armani, Banana 290 Fairfield Place Austin: 130 miles Republic Factory Store, Burberry, Calvin Klein Company Store, Coach, Mason Rd. San Antonio: 200 miles Cole Haan Outlet, David Yurman, DKNY Company Store, Elie Tahari 45 59 New Orleans, LA: 375 miles Outlet, Elizabeth Arden, Escada, Forever 21, kate spade new york, 99 290 610 Kenneth Cole Company Store, LACOSTE Outlet, Michael Kors Outlet, RETAIL NikeFactoryStore, Robert Graham, St. John, TAG Heuer, Talbots, Theory, 10 Tory Burch, True Religion, and many more exciting retailers. 10 Houston San Antonio GLA (sq. ft.) 542,000; 148 stores 610 Pasadena TOURISM / TRAFFIC 45 OPENING DATE Houston is the 4th largest city in the U.S. and the most populous city HOUSTON Opened March 2008 in Texas. With a population of over 5.7 million in the trade area and 6.3 PREMIUM OUTLETS Expanded 2010 million in the metro area, it ranks 5th in the U.S. Houston, known for its CYPRESS, TX oil and gas industries, also has the 2nd highest number of Fortune 500 companies after New York City. Houston’s Texas Medical Center is the PARKING RATIO largest medical center in the world with over 4.8 million patient visits 5.22:1 annually. Three airports form the 6th largest airport network in the world serving 52+ million passengers annually. Houston is home to The Houston Texans (NFL), The Houston Astros (MLB), and The Houston Rockets (NBA). -

2005-2006 North Houston Greenspoint Business Directory Nation’Snation’S #1#1

2005-2006 North Houston Greenspoint Business Directory Nation’sNation’s #1#1 Houston’s Largest AutoAuto Selection of Cars, Trucks, Vans & Utility Vehicles Fleet and Commercial Sales 281-820-8100 Message from the Chairman The Board of Directors and staff of the North Houston Greenspoint Chamber are proud to present this 2005 Business Directory. A new directory means we are full tilt into a new business year. The Chamber is off and running with programs galore, even at this writing. Your committees are in place and are working in your best interest. The Greater North Houston business community continues to be a major area of activity for the nation, as well as for Harris County. With the Bush Intercontinental Airport within minutes, major corporations at our front porch, and folks like you and me in the neighborhood, the future looks bright indeed! This Business Directory is for your convenience to be used as your “yellow pages for North Houston”. We urge you to enjoy it and use it to do business with Chamber members first. If there happens to be a type of service or product that you need and do not find in this book, please let us know and we will do our best to recruit a business to be a member of our Chamber to meet that need. Our Chamber is full of opportunities for your involvement and we hope you will take advantage of them. We should have a committee that you will feel comfortable with and have an interest in joining. Also, we have networking events that are a lot of fun and just might present a business lead. -

Family-Dollar-Aldinehoustontx.Pdf

family dollar New absolute NNN 260,000 residents in a 5-mile radius [ REPRESENTATIVE PHOTO ] IEW SIMILAR P O V RO T P K ER IC T • Build-to-suit location I L E C S • Increases throughout the base term and options portfolio • Rare infill high density location 366 Aldine Bender Rd., Houston, TX 77060 [ www.CapitalPacific.com ] Click for Map PROperty Summary Listing Team Contact Info THE SUBJect prOpertY IS A NEW NNN BUILD-TO-SUIT FAMILY RICK SANNER DOLLAR IN HOUSTON, TX WITH attractiVE 10% INCREASES IN [email protected] | (415) 274-2709 THE BASE TERM AND OptiONS. THE prOpertY IS FREEStaNDING, CA BRE# 01792433 IN A HIGH GROWTH, HIGH DENSITY AREA OF HOUSTON. THERE ARE aaron susman OVER $200,000 RESIDENTS WITHIN A 5-MILE RADIUS. [email protected] | (415) 481-0377 CA BRE# 01961568 PRICE: $2,085,113 CAP: 5.75% In conjunction with TX Licensed Broker: RENtabLE SF ...............8,353 SF Peter Ellis PRICE PER SF ...............$249.62 [email protected] | (210) 325-7578 LAND AREA ............... 0.89 AC CURRENT RENT ............$14.35/SF Capital Pacific collaborates. Click Here to meet the rest of our San Francisco team. faMILY DOLLAR | 2 [ REPRESENTATIVE PHOTO ] core characteristics LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS The subject property is located within the outer loop of Houston, TX, along Aldine Bender Rd., a highly-trafficked six lane thoroughfare. Monument Over 95K people within a 3-mile radius and signage provides excellent visibility. Aldine Bender Rd. connects commuters nearly 260K people within a 5-mile radius and residents to Interstate 45 to the west and Interstate 69 to the east.