Charles Farrar Browne The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Doing the Right Thing

On Doing the Right Thing AND OTHER ESSAYS ON DOING THE RIGHT THING AND OTHER ESSAYS by Albert Jay Nock 1918 HARPER fc? BROTHERS PUBLISHERS New York and London ON DOING THE RIGHT THING COPYRIGHT, j9ìS, BY HARPER & BROTHERS PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. FIRST EDITION To C. R. W. CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE IX ARTEMUS WARD I THE DECLINE OF CONVERSATION 2.$ ON MAKING LOW PEOPLE INTERESTING 48 A CULTURAL FORECAST 72. TOWARDS A NEW QUALITY-PRODUCT 97 ANARCHIST'S PROGRESS 12.3 ON DOING THE RIGHT THING i6l A STUDY IN MANNERS i79 THOUGHTS ON REVOLUTION 2.O3 TO YOUNGSTERS OF EASY MEANS 12.J Preface IUESB essays, except the first, were published in Harper's Magazine and The American Mercury within the last three years; the first one was printed as an introduction to a small volume, published in 1924 by A. and C. Boni, of selections from the writings of Artemus Ward. My best thanks are due Messrs. Boni and the editors of Harper's and the Mercury for permission to reprint them. They bear on various aspects of the same sub- ject, namely, the quality of civilization in the United States; and hence they have a certain unity, or a certain monotony, according as one is disposed to regard them. They are reprinted as they first appeared, without any changes worth speaking of. The exigencies of magazine publication, chiefly the haunting terror of a space limit, has had its effect upon their con- tinuity and completeness, and to some extent upon their manner, as well. -

The Development and Improvement Of

A CRITICAL STUDY OF JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN AND THE SLANG DICTIONARY A Dissertation by DRAGANA DJORDJEVIC Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Major Subject: English A CRITICAL STUDY OF JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN AND THE SLANG DICTIONARY A Dissertation by DRAGANA DJORDJEVIC Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, J. Lawrence Mitchell Committee Members, C. Jan Swearingen Jennifer Wollock Rodney C. Hill Head of Department, M. Jimmie Killingsworth May 2010 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT A Critical Study of John Camden Hotten and The Slang Dictionary. (May 2010) Dragana Djordjevic, B.A., University of Belgrade; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. J. Lawrence Mitchell Many lexicographers found some words unsuitable for inclusion in their dictionaries, thus the examination of general purpose dictionaries alone will not give us a faithful history of changes of the language. Nevertheless, by taking into account cant and slang dictionaries, the origins and history of such marginalized language can be truly examined. Despite people‘s natural fascination with these works, the early slang dictionaries have received relatively little scholarly attention, the later ones even less. This dissertation is written to honor those lexicographers who succeeded in a truthful documentation of nonstandard language. One of these disreputable lexicographers who found joy in an unending search for new and better ways of treating abstruse vocabulary was John Camden Hotten. -

Great Anniversary of a Tall Tale by the First Thoroughly American Writer

88 ПРЕГЛЕДНИ РАД УДК: 821.111(73).09 Slobodan D. Jovanović* Union University, Belgrade “Dr Lazar Vrkatić” Faculty of Law and Business studies, Novi Sad GREAT ANNIVERSARY OF A TALL TALE BY THE FIRST THOROUGHLY AMERICAN WRITER Abstract: The purpose of this article is to remind the readership that these days mark the 150th anniversary of publication of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County“, Mark Twain’s short story that in 1867 gave its title to his own first book. To be remembered is also the fact that Mark Twain was the first thoroughly American writer, who, unlike his literary predecessors and contemporaries, by conscious choice turned his back upon Europe. He held no reverence for ancient institutions and customs of the Old World and refused to celebrate its art, history, and cultural tradition. Accordingly, he also rejected the established patterns and conventions of English literature that shaped American writing up to the Civil War. He turned to his native land seeking to explore its resources in the realm of subject matter and language, as American reality of his days offered him rich material for story telling. His American types, localities, problems and situations are presented with vividness and familiarity of the first-hand experience, joined by his resolute experiment in language – he was the first to investigate the possibilities that American idiom offered for serious writing. He found the colloquial speech of common Americans a flexible, colourful, although sometimes * [email protected] G R E A T A NNIVERSARY OF A T A L L T ALE B Y T H E F I R S T T H O R O U G H L Y A M E R I C A N 89 W RITER vulgar, medium of expression, more stimulating than the intricate examples of educated and polite British English. -

Journalism Hall of Fame

UttiVt OHIO JOURNALISM HALL OF FAME Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Dinner- Meeting of Judges, Newspapermen, and Others to Honor the Journalists Elected Faculty Club Rooms November 20, 193 1, 6:30 p. m. c/~& Journalism Series, No. 10 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS MCMXXXII OHIO JOURNALISM HALL OF FAME Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Dinner- Meeting of Judges, Newspapermen, and Others to Honor the Journalists Elected Faculty Club Rooms November 1 1 p. m. 20, 93 , 6:30 Journalism Series, No. 10 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS MCMXXXII COMMITTEE OF JUDGES (193 I Election) H. W. Amos, The Jejfersonian, Cambridge. W. B. Baldwin, The Gazette, Medina. D. C. Bailev, The Banner, West Liberty Harry F. Busey, The Citizen, Columbus. Louis H. Brush, The News, Salem. Granville Barrere, The News-Herald, Hillsboro. Clarence J. Brown, Secretary of State, Columbus. Karlh Bull, The Herald, Cedarville. James M. Cox, The News, Dayton W. H. Cathcart, Director Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland W. R. Conaway, The Independent, Cardington J. A. Chew, The Gazette, Xenia. Roscoe Carle, The Times, Fostoria. C. R. Callahan, The Gazette, Bellevue. E. C. Dix, Sr., The Record, Wooster. William A. Duff, Ashland. F. A. Douglas, The Vindicator, Youngstown. J. A. Ey, Western Newspaper Lnion, Columbus. Mrs. Ruth Neeley France, The Post, Cincinnati. George H. Frank, The Citizen, Grafton. C. C. Fowler, The Dispatch, Canfield. T. H. Galbraith, The Disfatch, Columbus. C. B. Galbreath, Ohio Historical Society, Campus. O. P. Gayman, The Times, Canal Winchester. H. E. Griffith, The Morrow County Sentinel, Mt. Gilead. Alfred Haswell, The Sentinel-Tribune, Bowling Green. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School Certificate for Approving The

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of __________Peter McClelland Robinson__________ Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________________________ Director (Allan M. Winkler) ____________________________________________ Reader (Sheldon Anderson) ____________________________________________ Reader (Andrew R. L. Cayton) ____________________________________________ Reader (Marguerite S. Shaffer) ____________________________________________ Graduate School Representative (William J. Doan) ABSTRACT THE DANCE OF THE COMEDIANS: THE PEOPLE, THE PRESIDENT, AND THE PERFORMANCE OF POLITICAL STANDUP COMEDY IN AMERICA by Peter McClelland Robinson This dissertation argues that the emergent performance of political standup comedy became a significant agent for mediating and complicating the relationship between the American people and the American presidency, particularly during the middle half of the twentieth century. The Dance of the Comedians examines standup comedy—particularly its ramifications for the presidency and Americans’ perceptions of that institution—as a uniquely compelling form of cultural performance. Part ceremonial ritual and part playful improvisation, the performance of political comedy in its diverse forms became a potent site of liminality that empowered all of its constituents—the comic, the audience, and the object of the joke—to reexamine and renegotiate the roles of all concerned. It is this tripartite bond of reciprocal -

Charles Farrar Browne the Complete Works of Artemus

CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE THE COMPLETE WORKS OF ARTEMUS WARD PART VII 2008 – All rights reserved Non comercial use permited THE COMPLETE WORKS OF ARTEMUS WARD, PART 7, MISCELLANEOUS (CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE) With a biographical sketch by Melville D. Landon, "Eli Perkins" CONTENTS. PART VII. Miscellaneous. 7.1. The Cruise of the Polly Ann. 7.2. Artemus Ward's Autobiography. 7.3. The Serenade. 7.4. O'Bourcy's "Arrah-na-Pogue." 7.5. Artemus Ward among the Fenians. 7.6. Artemus Ward in Washington. 7.7. Scenes Outside the Fair Grounds. 7.8. The Wife. 7.9. A Juvenile Composition On the Elephant. 7.10. A Poem by the Same. 7.11. East Side Theatricals. 7.12. Soliloquy of a Low Thief. 7.13. The Negro Question. 7.14. Artemus Ward on Health. 7.15. A Fragment. 7.16. Brigham Young's Wives. 7.17. A. Ward's First Umbrella. 7.18. An Affecting Poem. 7.19. Mormon Bill of Fare. 7.20. "The Babes in the Wood." 7.21. Mr. Ward Attends a Graffick (Soiree.) 7.22. A. Ward Among the Mormons.--Reported by Himself--or Somebody Else. PART VII. MISCELLANEOUS. 7.1. THE CRUISE OF THE POLLY ANN. In overhaulin one of my old trunks the tother day, I found the follerin jernal of a vyge on the starnch canawl bote, Polly Ann, which happened to the subscriber when I was a young man (in the Brite Lexington of yooth, when thar aint no sich word as fale) on the Wabash Canawl: Monday, 2 P.M.--Got under wa. -

The Complete Works of Artemus Ward, Part 1

The Complete Works of Artemus Ward, Part 1 Charles Farrar Browne The Complete Works of Artemus Ward, Part 1 Table of Contents The Complete Works of Artemus Ward, Part 1....................................................................................................1 Charles Farrar Browne...................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY NOTES BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN.........................................................................4 A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH BY MELVILLE D. LANDON...................................................................6 INTRODUCTION BY T.W. ROBERTSON...............................................................................................12 PREFATORY NOTE...................................................................................................................................15 1.1. ONE OF MR. WARD'S BUSINESS LETTERS..................................................................................23 1.2. ON "FORTS.".......................................................................................................................................24 1.3. THE SHAKERS....................................................................................................................................25 1.4. HIGH−HANDED OUTRAGE AT UTICA..........................................................................................28 1.5. CELEBRATION AT BALDINSVILLE IN HONOR OF THE ATLANTIC CABLE........................29 -

California State University, Nohthridge Vanity Fair

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NOHTHRIDGE VANITY FAIR II AMERICAN HUl-IOR, 11359-63 A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction rJf tl1e requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by William A. Coonfield / .June, 1980 The thesis of William A. Coonfield is approved: p:r::ofessor '1arvi.n Klotz c:J Pro:fessorHichard Abcarian Professolf Arnotrt:l:-.f.:' stafford, Chairman California Stat.e University, Northridge ii TABLg OF CONTENTS Section ABSTRACT . .iv I THE TIMES 1 II FORJ'1S OF HUMOR 13 III REFORI1ERS AND REFOR11 41 IV ENDINGS . 70 In Sununary 70 Later Years 78 Effects . 79 In Re·trospect 81) NOTES . 84 BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 ····-···· ·-------: iii ABSTRACT VANITY F;\IR A."'!ERICAN HUMOR, 1859-63 by William A. Coonfield Master of Arts in English Vanity Fair was an American (New York City) humor publication from 1859-63. Managing editors w~Te Frank Wood, Cha-cles G. Leland, Charles Fa:..·rar Browne, and Charles Dawson Shanly. However, the St<o-,phens brothers held the magaziEe together; throughout the magazine's life, Henry Louis Stephens was art director, Allan Stephens was editor, and Louis St:ephens was pub lis.her. The magazine's stated intent was ·to view its day and age, condemn vice and praise merit, all for the ultimate pur pose of reformation. Fundamentally Democratic, the ma.ga zine came to r<>r;pect and extoll Lincoln. Cartoons, jokes, puns, cacograp:1y, cor:unent on current speech and events, proverbs, fu.l:-les, parody~ verse, and satirical. sketch(~S iv poked fun at cultural variations and satirized international, state, and metropolitan political figures and reformers. -

Charles Farrar Browne the Complete Works of Artemus

CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE THE COMPLETE WORKS OF ARTEMUS WARD PART IV 2008 – All rights reserved Non comercial use permited THE COMPLETE WORKS OF ARTEMUS WARD PART 4, TO CALIFORNIA AND RETURN (CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE) With a biographical sketch by Melville D. Landon, "Eli Perkins" CONTENTS. PART IV. TO CALIFORNIA AND RETURN. 4.1. On the Steamer. 4.2. The Isthmus. 4.3. Mexico. 4.4. California. 4.5. Washoe. 4.6. Mr. Pepper. 4.7. Horace Greeley's Ride to Placerville. 4.8. To Reese River. 4.9. Great Salt Lake City. 4.10. The Mountain Fever. 4.11. "I am Here." 4.12. Brigham Young. 4.13. A Piece is Spoken. 4.14. The Ball. 4.15. Phelp's Almanac. 4.16. Hurrah for the Road. 4.17. Very Much Married. 4.18. The Revelation of Joseph Smith. PART IV. TO CALIFORNIA AND RETURN. 4.1. ON THE STEAMER. New York, Oct. 13, 1868. The steamer Ariel starts for California at noon. Her decks are crowded with excited passengers, who instantly undertake to "look after" their trunks and things; and what with our smashing against each other, and the yells of the porters, and the wails over lost baggage, and the crash of boxes, and the roar of the boilers, we are for the time being about as unhappy a lot of maniacs as was ever thrown together. I am one of them. I am rushing around with a glaring eye in search of a box. Great jam, in which I find a sweet young lady, with golden hair, clinging to me fondly, and saying, "Dear George, farewell!"-- Discovers her mistake, and disappears. -

Artemus Ward Collection Charles Farrar Browne

ARTEMUS WARD COLLECTION CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE ARTEMUS WARD (April 26, 1834 – March 6, 1867, born Charles Farrar Brown[e]) was one of America's greatest humorists of the nineteenth century. He was patronized eagerly from coast to coast in his writings and stand-up comedy "lecture" performances. During a tour of the West in 1863-64, he befriended the somewhat younger Samuel Clemens (as yet a relative unknown), and then nearly died of a fever in Salt Lake City where admiring residents nursed him back to health. Thenceforth, his principal topics and entertainments centered around his experience among the Mormons, whom he caricatured fondly to full houses, and in large publication runs of his various books. Ward was enjoyed by Abraham Lincoln and applauded in crowded halls across the nation. He was ultimately praised and courted by sophisticated readers and audiences in London, where he gave his final performance on January 23, 1867, dying soon afterward before reaching his thirty-third birthday. For an overview of the life of Charles Farrar Browne, see a biographical article in the Dictionary of American Biography III:162-64, nicely written by the celebrated Canadian humorist and author Stephen Leacock. For works quoted in this article, see the listing of SOURCES CITED, at the end. 2 THE COLLECTION assembled here includes: – Five autograph LETTERS signed by Ward, with good humor. Items 1-5. – Three contemporary albumen PHOTOGRAPHS of Ward, clearly showing his physical decline after his sickness in Salt Lake City (and curled hair, referenced in his subsequent lectures and in the London manuscript below). -

Artemus Ward (Charles Farrar Browne) Part 7 the COMPLETE WORKS

Artemus Ward (Charles Farrar Browne) Part 7 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF ARTEMUS WARD, PART 7, MISCELLANEOUS (CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE) With a biographical sketch by Melville D. Landon, "Eli Perkins" CONTENTS. PART VII. Miscellaneous. 7.1. The Cruise of the Polly Ann. 7.2. Artemus Ward's Autobiography. 7.3. The Serenade. page 1 / 91 7.4. O'Bourcy's "Arrah-na-Pogue." 7.5. Artemus Ward among the Fenians. 7.6. Artemus Ward in Washington. 7.7. Scenes Outside the Fair Grounds. 7.8. The Wife. 7.9. A Juvenile Composition On the Elephant. 7.10. A Poem by the Same. 7.11. East Side Theatricals. 7.12. Soliloquy of a Low Thief. 7.13. The Negro Question. 7.14. Artemus Ward on Health. page 2 / 91 7.15. A Fragment. 7.16. Brigham Young's Wives. 7.17. A. Ward's First Umbrella. 7.18. An Affecting Poem. 7.19. Mormon Bill of Fare. 7.20. "The Babes in the Wood." 7.21. Mr. Ward Attends a Graffick (Soiree.) 7.22. A. Ward Among the Mormons.--Reported by Himself--or Somebody Else. PART VII. MISCELLANEOUS. 7.1. THE CRUISE OF THE POLLY ANN. In overhaulin one of my old trunks the tother day, I found the follerin jernal of a vyge on the starnch canawl bote, Polly Ann, page 3 / 91 which happened to the subscriber when I was a young man (in the Brite Lexington of yooth, when thar aint no sich word as fale) on the Wabash Canawl: Monday, 2 P.M.--Got under wa. Hosses not remarkable frisky at fust. -

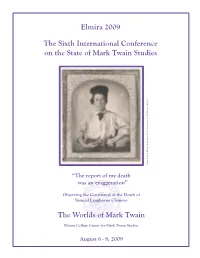

Elmira 2009 Conference Program

Elmira 2009 The Sixth International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. of California, Bancroft University Library, Papers, Twain Mark “The report of my death was an exaggeration” Observing the Centennial of the Death of Samuel Langhorne Clemens The Worlds of Mark Twain Elmira College Center for Mark Twain Studies August 6 - 8, 2009 Mark Twain Exhibit Open 9 am to 5 pm Open 9 am to 5 pm Open 8:30 am to 5 pm on Thursday and Friday 11 am to 2 pm on Saturday SHUTTLE PICK-UP POINT: Woodlawn To Cemetery -- Saturday afternoon To Quarry Farm Picnic -- Saturday evening Refreshments available: 10:15 am to 10:25 am GANNETT-TRIPP LIBRARY: 2:15 pm to 2:25 pm EMERSON HALL: irstF floor : owerL level: CAMPUS CENTER: 3:45 pm to 355 pm Registration (Panels)Tripp Lecture Hall Gibson Theatre irstF floor: Second floor: Plenary Session: 28.Olivia Langdon Statue Book Sales Tifft Lounge (Panels) Dining Hall Shirt and Mug Sales condSe floor: Robert H. Hirst Mark Twain Statue Buechner Room (Panels) Keynote Address: Mark Twain Archive George Waters Gallery: Open 12:30 pm to 1 pm Russell Banks Mark Twain in the Comics Closing Roundtable See Mark Woodhouse Mackenzie’s (Breakfast) to arrange additional visits. The Sixth International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies The Worlds of Mark Twain Wednesday, August 5th 9 am - 9:30 pm REGISTRATION Gannett-Tripp Library After 9:30 pm Please go to the Campus Security Office Tompkins Hall to pick up your Conference packet and keys.