Amalfi, Byzantium, and the Vexed Question Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

2014 State of Ivory Demand in China

2012–2014 ABOUT WILDAID WildAid’s mission is to end the illegal wildlife trade in our lifetimes by reducing demand through public awareness campaigns and providing comprehensive marine protection. The illegal wildlife trade is estimated to be worth over $10 billion (USD) per year and has drastically reduced many wildlife populations around the world. Just like the drug trade, law and enforcement efforts have not been able to resolve the problem. Every year, hundreds of millions of dollars are spent protecting animals in the wild, yet virtually nothing is spent on stemming the demand for wildlife parts and products. WildAid is the only organization focused on reducing the demand for these products, with the strong and simple message: when the buying stops, the killing can too. Via public service announcements and short form documentary pieces, WildAid partners with Save the Elephants, African Wildlife Foundation, Virgin Unite, and The Yao Ming Foundation to educate consumers and reduce the demand for ivory products worldwide. Through our highly leveraged pro-bono media distribution outlets, our message reaches hundreds of millions of people each year in China alone. www.wildaid.org CONTACT INFORMATION WILDAID 744 Montgomery St #300 San Francisco, CA 94111 Tel: 415.834.3174 Christina Vallianos [email protected] Special thanks to the following supporters & partners PARTNERS who have made this work possible: Beijing Horizonkey Information & Consulting Co., Ltd. Save the Elephants African Wildlife Foundation Virgin Unite Yao Ming Foundation -

Byzantine Conquests in the East in the 10 Century

th Byzantine conquests in the East in the 10 century Campaigns of Nikephoros II Phocas and John Tzimiskes as were seen in the Byzantine sources Master thesis Filip Schneider s1006649 15. 6. 2018 Eternal Rome Supervisor: Prof. dr. Maaike van Berkel Master's programme in History Radboud Univerity Front page: Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas entering Constantinople in 963, an illustration from the Madrid Skylitzes. The illuminated manuscript of the work of John Skylitzes was created in the 12th century Sicily. Today it is located in the National Library of Spain in Madrid. Table of contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1 - Byzantine-Arab relations until 963 7 Byzantine-Arab relations in the pre-Islamic era 7 The advance of Islam 8 The Abbasid Caliphate 9 Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty 10 The development of Byzantine Empire under Macedonian dynasty 11 The land aristocracy 12 The Muslim world in the 9th and 10th century 14 The Hamdamids 15 The Fatimid Caliphate 16 Chapter 2 - Historiography 17 Leo the Deacon 18 Historiography in the Macedonian period 18 Leo the Deacon - biography 19 The History 21 John Skylitzes 24 11th century Byzantium 24 Historiography after Basil II 25 John Skylitzes - biography 26 Synopsis of Histories 27 Chapter 3 - Nikephoros II Phocas 29 Domestikos Nikephoros Phocas and the conquest of Crete 29 Conquest of Aleppo 31 Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas and conquest of Cilicia 33 Conquest of Cyprus 34 Bulgarian question 36 Campaign in Syria 37 Conquest of Antioch 39 Conclusion 40 Chapter 4 - John Tzimiskes 42 Bulgarian problem 42 Campaign in the East 43 A Crusade in the Holy Land? 45 The reasons behind Tzimiskes' eastern campaign 47 Conclusion 49 Conclusion 49 Bibliography 51 Introduction In the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors coming from the Macedonian dynasty. -

Maxi-Catalogue 2014 Maxi-Catalogue 2014

maxi-catalogue 2014 maxi-catalogue 2014 New publications coming from Alexander Press: 1. Διερχόμενοι διά τού Ναού [Passing Through the Nave], by Dimitris Mavropoulos. 2. Εορτολογικά Παλινωδούμενα by Christos Yannaras. 3. SYNAXIS, The Second Anthology, 2002–2014. 4. Living Orthodoxy, 2nd edition, by Paul Ladouceur. 5. Rencontre avec λ’οrthodoxie, 2e édition, par Paul Ladouceur. 2 Alexander Press Philip Owen Arnould Sherrard CELEBR ATING . (23 September 1922 – 30 May 1995 Philip Sherrard Philip Sherrard was born in Oxford, educated at Cambridge and London, and taught at the universities of both Oxford and London, but made Greece his permanent home. A pioneer of modern Greek studies and translator, with Edmund Keeley, of Greece’s major modern poets, he wrote many books on Greek, Orthodox, philosophical and literary themes. With the Greek East G. E. H. Palmer and Bishop Kallistos Ware, he was and the also translator and editor of The Philokalia, the revered Latin West compilation of Orthodox spiritual texts from the 4th to a study in the christian tradition 15th centuries. by Philip Sherrard A profound, committed and imaginative thinker, his The division of Christendom into the Greek East theological and metaphysical writings covered issues and the Latin West has its origins far back in history but its from the division of Christendom into the Greek East consequences still affect western civilization. Sherrard seeks and Latin West, to the sacredness of man and nature and to indicate both the fundamental character and some of the the restoration of a sacred cosmology which he saw as consequences of this division. He points especially to the the only way to escape from the spiritual and ecological underlying metaphysical bases of Greek Christian thought, and contrasts them with those of the Latin West; he argues dereliction of the modern world. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Manolis G. Varvounis * – Nikos Rodosthenous Religious

Manolis G. Varvounis – Nikos Rodosthenous Religious Traditions of Mount Athos on Miraculous Icons of Panagia (The Mother of God) At the monasteries and hermitages of Mount Athos, many miraculous icons are kept and exhibited, which are honored accordingly by the monks and are offered for worship to the numerous pilgrims of the holy relics of Mount Athos.1 The pil- grims are informed about the monastic traditions of Mount Athos regarding these icons, their origin, and their miraculous action, during their visit to the monasteries and then they transfer them to the world so that they are disseminated systemati- cally and they can become common knowledge of all believers.2 In this way, the traditions regarding the miraculous icons of Mount Athos become wide-spread and are considered an essential part of religious traditions not only of the Greek people but also for other Orthodox people.3 Introduction Subsequently, we will examine certain aspects of these traditions, based on the literature, notably the recent work on the miraculous icons in the monasteries of Mount Athos, where, except for the archaeological and the historical data of these specific icons, also information on the wonders, their origin and their supernatural action over the centuries is captured.4 These are information that inspired the peo- ple accordingly and are the basis for the formation of respective traditions and re- ligious customs that define the Greek folk religiosity. Many of these traditions relate to the way each icon ended up in the monastery where is kept today. According to the archetypal core of these traditions, the icon was thrown into the sea at the time of iconoclasm from a region of Asia Minor or the Near East, in order to be saved from destruction, and miraculously arrived at the monastery. -

Byzantine Legal Culture and the Roman Legal Tradition, 867-1056 1St Edition Download Free

BYZANTINE LEGAL CULTURE AND THE ROMAN LEGAL TRADITION, 867-1056 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Zachary Chitwood | 9781107182561 | | | | | Byzantine Empire See also: Byzantine Empire under the Heraclian dynasty. Retrieved February 23, Theophylact Patriarch of Constantinople With the exception of a few cities, and especially Constantinoplewhere other 867-1056 1st edition of urban economic activities were also developed, Byzantine society remained at its heart agricultural. Born in at ArabissusCappadocia. The Persian Empire is the name given to a series of dynasties centered in modern-day Iran that spanned several Byzantine Legal Culture and the Roman Legal Tradition the sixth century B. Amorian dynasty — [ edit ] See also: Byzantine Empire under the Amorian dynasty. After becoming the emperor's father-in-law, he successively assumed higher offices until he crowned himself senior emperor. Named his sons MichaelAndronikos and Konstantios as co-emperors. In: L. Only son of Andronikos III, he had not been crowned co-emperor or declared heir at his father's death, a fact which led to the outbreak of a destructive civil war between his regents and his father's closest aide, John VI Kantakouzenoswho was crowned co-emperor. Imitating the Campus in Rome, similar grounds were developed in several other urban centers and military settlements. The city also had several theatersgymnasiaand many tavernsbathsand brothels. The "In Trullo" or "Fifth-Sixth Council", known for its canons, was convened in the years of Justinian II — and occupied itself exclusively with matters of discipline. Live TV. Inthe barbarian Odoacer overthrew the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustusand Rome had fallen. They never absolutized natural rights or Roman law or even the Roman people. -

Ancient DNA Reveals the Chronology of Walrus Ivory Trade from Norse Greenland

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/289165; this version posted March 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Title: Ancient DNA reveals the chronology of walrus ivory trade from Norse Greenland Short title: Tracing the medieval walrus ivory trade Bastiaan Star1*†, James H. Barrett2*†, Agata T. Gondek1, Sanne Boessenkool1* * Corresponding author † These authors contributed equally 1 Centre for Ecological and Evoluionary Synthesis, Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo, PO Box 1066, Blindern, N-0316 Oslo, Norway. 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3ER, United Kingdom. Keywords: High-throughput sequencing | Viking Age | Middle Ages | aDNA | Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/289165; this version posted March 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The search for walruses as a source of ivory –a popular material for making luxury art objects in medieval Europe– played a key role in the historic Scandinavian expansion throughout the Arctic region. Most notably, the colonization, peak and collapse of the medieval Norse colony of Greenland have all been attributed to the proto-globalization of ivory trade. -

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi A struggle for supremacy 867 - 1071 J.J.P. Vrijaldenhoven S0921084 Van Speijkstraat 76-II 2518 GE ’s Gravenhage Tel.: 0628204223 E-mail: [email protected] Master Thesis Europe 1000 - 1800 Prof. Dr. P. Stephenson and Prof. Dr. P.C.M. Hoppenbrouwers History University of Leiden 30-07-2014 CONTENTS GLOSSARY 2 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 1 THE FIRST STRUGGLE OF THE DYNATOI AND THE STATE 867 – 959 16 STATE 18 Novel (A) of Leo VI 894 – 912 18 Novels (B and C) of Romanos I Lekapenos 922/928 and 934 19 Novels (D, E and G) of Constantine VII Porphyrogenetos 947 - 959 22 CHURCH 24 ARISTOCRACY 27 CONCLUSION 30 CHAPTER 2 LAND OWNERSHIP IN THE PERIOD OF THE WARRIOR EMPERORS 959 - 1025 32 STATE 34 Novel (F) of Romanos II 959 – 963. 34 Novels (H, J, K, L and M) of Nikephoros II Phokas 963 – 969. 34 Novels (N and O) of Basil II 988 – 996 37 CHURCH 42 ARISTOCRACY 45 CONCLUSION 49 CHAPTER 3 THE CHANGING STATE AND THE DYNATOI 1025 – 1071 51 STATE 53 CHURCH 60 ARISTOCRACY 64 Land register of Thebes 65 CONCLUSION 68 CONCLUSION 70 APPENDIX I BYZANTINE EMPERORS 867 - 1081 76 APPENDIX II MAPS 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 82 1 Glossary Aerikon A judicial fine later changed into a cash payment. Allelengyon Collective responsibility of a tax unit to pay each other’s taxes. Anagraphis / Anagrapheus Fiscal official, or imperial tax assessor, who held a role similar as the epoptes. Their major function was the revision of the tax cadastre. It is implied that they measured land and on imperial order could confiscate lands. -

China's Ivory Traders Are Moving Online

CHINA’S IVORY AN APPROACH TO THE CONFLICT BETWEEN TRADITION AND ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITY Sophia I. R. Kappus S1994921 [email protected] MA Arts & Culture – Design, Culture & Society Universiteit Leiden Supervisor: Prof. Dr.. R. Zwijnenberg Second Reader: Final Version: 07.12.2017 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. The History of Chinese Ivory Carving ..................................................................................... 7 1.1 A Brief overview............................................................................................................ 7 1.2 The Origins and Characteristics of Ivory .......................................................................... 7 1.3 Ivory Carvings throughout history ................................................................................... 9 1.4 From the Material to the Animal – The Elephant in Chinese Culture ................................ 13 2. Ivory in Present Day China................................................................................................... 17 2.1 Chinese National Pride and Cultural Heritage................................................................. 17 2.2 Consumers and Collectors............................................................................................. 19 2.3 The Artist’s Responsibility............................................................................................ 24 -

Pompey and Cicero: an Alliance of Convenience

POMPEY AND CICERO: AN ALLIANCE OF CONVENIENCE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of ARTS by Charles E. Williams Jr., B.A. San Marcos, Texas May 2013 POMPEY AND CICERO: AN ALLIANCE OF CONVENIENCE Committee Members Approved: ______________________________ Pierre Cagniart, Chair ______________________________ Kenneth Margerison ______________________________ Elizabeth Makowski Approved: ______________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Charles E. Williams Jr. 2013 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94- 553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Charles E. Williams Jr., authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Above all I would like to thank my parents, Chuck and Kay Williams, for their continuing support, assistance, and encouragement. Their desire to see me succeed in my academic career is perhaps equal to my own. Thanks go as well to Dr Pierre Cagnart, without whom this work would not have been possible. His expertise in Roman politics and knowledge concerning the ancient sources were invaluable. I would also like to thank Dr. Kenneth Margerison and Dr. Elizabeth Makowski for critiquing this work and many other papers I have written as an undergraduate and graduate student. -

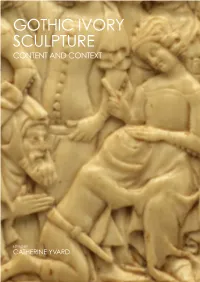

Gothic Ivory Sculpture Content and Context

GOTHIC IVORY SCULPTURE CONTENT AND CONTEXT EDITED BY CATHERINE YVARD Gothic Ivory Sculpture: Content and Context Edited by Catherine Yvard With contributions by: Elisabeth Antoine-König Katherine Eve Baker Camille Broucke Jack Hartnell Franz Kirchweger Juliette Levy-Hinstin Christian Nikolaus Opitz Stephen Perkinson Naomi Speakman Michele Tomasi Catherine Yvard Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Managing Editor: Maria Mileeva Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2017, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-09-1. Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. All rights reserved. Designed by Matthew Cheale Cover Image: Detail of Fig. 10.1, London, The British Museum, Inv.