Day Surgery Development and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CST-On-Demand-Binder.Pdf

Zander Perioperative Education Zander CST Exam Preparation Course Zander Perioperative Education Certification Preparation for CNOR, CAPA-CPAN, CST and CBSPD Wendy Zander MSN/Ed, RN, CNOR [email protected] Test Taking Strategies Objectives: 1. Apply Test Taking Strategies for the CST exam 2. Create a Personal Study Plan 3. Eligibility • Registering for the exam • Exam Format • Time Management • Test Taking Strategies Eligibility • Current or previously Certified Surgical Technologist (CST) ▫ Evidence of CST Certification • Graduate of a surgical technology program accredited by CAAHEP ▫ Evidence of proof of graduation • Graduate of a surgical technology accredited by ABHES ▫ Evidence of proof of graduation www.periop-ed.com 1 Zander Perioperative Education Military Eligible • A graduate of a military training program in surgical technology is always eligible whether it was before, during or after having CAAHEP accreditation. ▫ a copy of your DD214 (must state location of the base where program was completed), ▫ a copy of your graduation certificate from the surgical technology training program ▫ a smart transcript Accelerated Alternate Delivery (AAD) Pathway • Have on-the-job training in surgical technology • Are a graduate from a surgical technology program that did not hold CAAHEP accreditation during your enrollment CST Testing Fees First Time Test Takers Exam Fee (AST Members) Exam Fee (Non Members) $190 $290 Current or Previous Certified Surgical Technologist Renewing First Time Test Takers Certification by Examination Exam Fee -

Minimal Endoscope-Assisted Thyroidectomy Through a Retroauricular Approach: an Evolving Solo Surgery Technique

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Minimal Endoscope-assisted Thyroidectomy Through a Retroauricular Approach: An Evolving Solo Surgery Technique Myung Jin Ban, MD,*w Jae Won Chang, MD,z Won Shik Kim, MD,y Hyung Kwon Byeon, MD, PhD,y Yoon Woo Koh, MD, PhD,y and Jae Hong Park, MD, PhD* (RA), or transoral approach.1–5 Endoscopic thyroidectomy Abstract: This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of through an RA approach is an especially excellent choice minimal endoscope-assisted thyroidectomy (MEAT) through a for head and neck surgeons because of their familiarity with retroauricular (RA) approach. Most of the thyroidectomy oper- the direction of the approach, the short distance to the ative time was accounted for by direct visualization through the thyroid gland, and a good cosmetic outcome without the RA window, minimizing interference between surgical instruments. 6 Endoscope use was minimized and limited to critical surgical need for additional incisions. aspects, including preservation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and Despite the advantages of the RA approach, funda- parathyroid glands. The recurrent laryngeal nerve was neuro- mental limitations of endoscopic surgery still exist, includ- monitored throughout the procedure. MEAT through an RA ing a narrow operative field that restricts the free movement approach was performed in 8 patients with papillary thyroid car- of instruments. Gas insufflation, an additional incision for cinoma (mean tumor size, 1.2 ± 0.5 cm). The mean patient age was the endoscope port, robotic arm assistance, and a flexible 41.1 ± 7.5 years. The endoscopic operating time was endoscope holder for solo surgery have all been used to 19 ± 3.4 minutes, and no postoperative hematoma, seroma, or overcome this limitation.3,7,8 vocal cord paralysis was observed. -

UNMH Orthopedic Surgery Clinical Privileges

UNMH Orthopedic Surgery Clinical Privileges Name: Effective Dates: To: o Initial privileges (initial appointment) o Renewal of privileges (reappointment) o Expansion of privileges (modification) All new applicants must meet the following requirements as approved by the UNMH Board of Trustees effective: 05/30/2014 INSTRUCTIONS Applicant: Check off the "Requested" box for each privilege requested. Applicants have the burden of producing information deemed adequate by the Hospital for a proper evaluation of current competence, current clinical activity, and other qualifications and for resolving any doubts related to qualifications for requested privileges. Department Chair: Check the appropriate box for recommendation on the last page of this form. If recommended with conditions or not recommended, provide condition or explanation on the last page of this form. OTHER REQUIREMENTS 1. Note that privileges granted may only be exercised at UNM Hospitals and clinics that have the appropriate equipment, license, beds, staff, and other support required to provide the services defined in this document. Site-specific services may be defined in hospital or department policy. 2. This document defines qualifications to exercise clinical privileges. The applicant must also adhere to any additional organizational, regulatory, or accreditation requirements that the organization is obligated to meet. Qualifications for Orthopedic Surgery Practice Area Code: 42 Version Code: 05-2014a Initial Applicant - To be eligible to apply for privileges in orthopedic -

Wrvus: Do They Really Measure the Workload and Complexity of What We Do?

wRVUs: Do They Really Measure the Workload and Complexity Of What We Do? Raj S. Pruthi MD MHA FACS Rhodes Distinguished Professor and Chair Department of Urology The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill INTRODUCTION Productivity-based Compensation • InCreasing use of wRVU in employed Compensation models • 2007 (16%) à 2016 (> 60%) • Use of benChmarked data (MGMA, AMGA, SC) to determine compensation/produCtivity ($/wRVU) • e.g. AMGA $441,836 / 7649 = $57.76/wRVU 2 INTRODUCTION wRVU • RBRVS - Developed for HCFA by Hsaio et al (1986-92) • Passed in 1989 -- implemented in 1992 INTRODUCTION Work RVU x Work GPCI + Practice Expense RVU x PE GPCI Conversion Payment = x FaCtor Rate + Malpractice RVU x MP GPCI GPCI = geographiC praCtiCe Cost index INTRODUCTION • RVUs à metric of physician productivity • RVUs : CPT code 405 urologiCal serviCes 22 383 Work = Time x Intensity INTRODUCTION Work 100 units INTRODUCTION • RVU assignments initially made in consultation with nominees from various medical specialties • Quarterly adjustments based on survey data • Zero sum game INTRODUCTION Changes to Work RVUs RUC Summary of Recommendation INTRODUCTION Who Gets Surveys? • Respondents seleCted by AUA by random sampling • May be sub-speCialty, e.g. prosthetiCs • May be general, e.g. cysto with dilation • Private praCtiCe (small & large), hospital-based, and aCademiC • Need at least 30-50 responses -- ideally >100 responses INTRODUCTION • Subjective methodology linked with compensation • Accurate measure of surgical complexity? workload? effort? time? -

06-1733 ) Issued: October 17, 2006 DEPARTMENT of the NAVY, MARINE ) CORPS, Camp Lejeune, NC, Employer ) ______)

United States Department of Labor Employees’ Compensation Appeals Board __________________________________________ ) L.S., Appellant ) ) and ) Docket No. 06-1733 ) Issued: October 17, 2006 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY, MARINE ) CORPS, Camp LeJeune, NC, Employer ) __________________________________________ ) Appearances: Case Submitted on the Record Appellant, pro se Office of Solicitor, for the Director DECISION AND ORDER Before: ALEC J. KOROMILAS, Chief Judge MICHAEL E. GROOM, Alternate Judge JAMES A. HAYNES, Alternate Judge JURISDICTION On July 24, 2006 appellant filed a timely appeal from the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs’ June 9, 2006 merit decision terminating her compensation. Pursuant to 20 C.F.R. §§ 501.2(c) and 501.3(d)(2), the Board has jurisdiction over the merits of this case. ISSUE The issue is whether the Office met its burden of proof to terminate appellant’s compensation effective June 10, 2006 on the grounds that she no longer had residuals of her employment injury after that date. FACTUAL HISTORY On May 5, 2000 appellant, then a 52-year-old registered dental hygienist, filed an occupational disease claim alleging that she sustained a ganglion cyst on the dorsum of her right wrist due to repeatedly grasping instruments at work. The Office accepted that appellant sustained a ganglion cyst of her right wrist. She stopped work on May 5, 2000 to undergo an excision of the mass of her ganglion cyst and repair of the extensor tendon of the right long finger. The surgery was performed by Dr. Richard S. Bahner, an attending Board-certified orthopedic surgeon, and was authorized by the Office. In July 2000, appellant returned to light-duty work on a full-time basis for the employing establishment. -

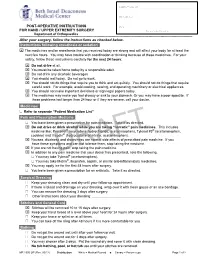

POST-OPERATIVE INSTRUCTIONS for HAND / UPPER EXTREMITY SURGERY Department of Orthopaedics ------After Your Surgery, Follow the Instructions As Checked Below

POST-OPERATIVE INSTRUCTIONS FOR HAND / UPPER EXTREMITY SURGERY Department of Orthopaedics --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- After your surgery, follow the instructions as checked below. Instructions following anesthesia or sedation The medicines and/or anesthesia that you received today are strong and will affect your body for at least the next few hours. You may have trouble with coordination or thinking because of these medicines. For your safety, follow these instructions carefully for the next 24 hours: Do not drive at all. You must be taken home today by a responsible adult. Do not drink any alcoholic beverages You should rest today. Do not go to work. You should not do things that require you to think and act quickly. You should not do things that require careful work. For example, avoid cooking, sewing, and operating machinery or electrical appliances. You should not make important decisions or sign legal papers today. The medicines may make you feel drowsy or sick to your stomach. Or you may have a poor appetite. If these problems last longer than 24 hour or if they are severe, call your doctor. Medicines Refer to separate “Patient Medication List” Pain and Prescription Medicine You have been given a prescription for pain medicine. Take it as directed. Do not drive or drink alcohol while you are taking “narcotic” pain medicines. This includes medicine like: Percocet® (oxycodone hydrochloride; acetaminophen), Tylenol #3® (acetaminophen; codeine) and Vicodin® (hydrocodone bitartrate; acetaminophen). Nausea, dizziness and drowsiness are normal side effects of prescribed pain medicine. If you have these symptoms and can not tolerate them, stop taking the medicine. -

Urology Scientific Session Monday, September 28, 2020

Urology Scientific Session Monday, September 28, 2020 Moderators/Panelists: Drs. Sabine Zundel, Sameh Shehata, Holger Till, Yuri Kozlov, Philipp Szavay, Eduardo Perez (S26) PNEUMOVESICOSCOPIC CORRECTION OF PRIMARY VESICOURETERAL REFLUX (VUR) IN CHILDREN. - OUR INITIAL EXPERIENCE- A. M. Benaired, Pediatric, Surgeon; H Zahaf, Pediatric, Surgeon; Military Central Hospital Purpose: Vesicoureteral reflux is a common urological abnormality predisposing risk of childhood hypertension and chronic renal failure. It is called primitive when it is due to an abnormality of the vesicoureteral junction. Different treatment approaches have been proposed a long time. Two main trends can be identified, conservative and operative approach. The main objective of our prospective study is to demonstrate the feasibility of vesicoscopic crosstrigonal ureteral reimplantation under CO2 pneumovesicum in treatment on primary vesicoureteral reflux and analyze results of this approach. Methods: A total of 60 patients underwent transvesicoscopic ureteral reimplantation (33 boys, 27 girls) by the same surgeon from Mai 2011 to Mai 2015. All patients had primary vesicoureteral reflux, and surgery was performed because of breakthrough urinary tract infection despite antibiotic prophylaxis, persistent high grade of vesicoureteral reflux especially in association with significant renal scarring, mean age at operation was 47.47 month (5 month - 12 years). Of the 60 patients, 34 had bilateral reflux and 26 had unilateral reflux. The reflux grade in the total of 94 ureters was grade IV, V in 59.57%, grade III in 35.11% and grade II in 5.32% in association with contralateral high grade vesicoureteral reflux. Our surgical methods followed those reported by Valla et al. Results: The transvesicoscopic procedure was successfully completed in all patients without perioperative complication except one case of pneumoperitoneum that required exsufflation by open laparoscopy. -

Laparoscopic Ureteral Repair in Gynaecological Surgery Carlo De Ciccoa, Anastasia Ussiab and Philippe Robert Koninckxb,C

Laparoscopic ureteral repair in gynaecological surgery Carlo De Ciccoa, Anastasia Ussiab and Philippe Robert Koninckxb,c aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Purpose of review University Hospital A. Gemelli, Universita` Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, bGruppo Italo-Belga, Rome, Italy and To review laparoscopic surgery in the treatment options for ureteral lesions in cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, gynaecological surgery. University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Katholieke Recent findings Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium Laparoscopic treatment of ureteral injuries has been increasingly reported over the past Correspondence to Dr Carlo De Cicco, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital A. years. Treatment has progressively shifted from ureteroneocystostomy performed by Gemelli, Universita` Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Largo F. laparotomy to less invasive treatment options such as ureteral stenting or dilatation in Vito 1, 00168 Rome, Italy Tel: +39 06 30155131; case of stricture, stenting under laparoscopic guidance and laparoscopic stitching of e-mail: [email protected] lacerations, laparoscopic ureteral reanastomosis or laparoscopic Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology ureteroneocystostomy for transections. Deep endometriosis surgery of an associated 2011, 23:296–300 hydronephrosis is associated with a high incidence of ureteral lesions making preoperative stenting desirable in order to facilitate the eventual repair, while avoiding the more problematic insertion of a stent after a lesion is made. The available data confirm the excellent outcome of stenting obstructive lesions. When stenting proves difficult or in case of a ureteral leakage, laparoscopic aided stenting is strongly suggested, in order to avoid further damage while permitting simultaneous repair if necessary. Laparoscopic suturing of a laceration over a stent is clearly superior to stenting only. -

Basic Standards for Fellowship Training in Orthopedic Hand Surgery BOT 7/2011, Effective 7/2012 Page 2

Basic Standards for Fellowship Training in Orthopedic Hand Surgery American Osteopathic Association and American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics TABLE OF CONTENTS Article I: Introduction .................................................................................................. 3 Article II: Mission ........................................................................................................... 3 Article III Educational Program Goals/Core Competencies .................................... 3 Article IV: Institutional Requirements .......................................................................... 3 Article V: Program Requirements and Content .......................................................... 4 Article VI: Program Director / Faculty Qualifications ............................................... 5 Article VII: Fellow Requirements ..................................................................................... 5 Article VIII: Evaluation ....................................................................................................... 5 Basic Standards for Fellowship Training in Orthopedic Hand Surgery BOT 7/2011, Effective 7/2012 Page 2 Basic Standards for Fellowship Training in Orthopedic Hand Surgery This is an amendment to the Basic Standards for Residency Training in Orthopedic Surgery which governs and defines orthopedic surgical training. The Basic Standards are, therefore, incorporated into this document. SECTION I - INTRODUCTION These are the Basic Standards for Fellowship Training in Orthopedic -

Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical Practice Prasad P

Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical Practice Prasad P. Godbole • Martin A. Koyle Duncan T. Wilcox (Editors) Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical Practice Editors Prasad P. Godbole Martin A. Koyle Department of Pediatric Surgery Department of Urology and Urology and Pediatrics Sheffield Children’s Hospital University of Washington Sheffield, UK and Department of Urology Duncan T. Wilcox and Pediatrics Department of Pediatric Urology Seattle Children’s Hospital Denver Children’s Hospital Seattle, WA University of Colorado at Denver USA Denver, CO USA ISBN 978-1-84996-365-7 e-ISBN 978-1-84996-366-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-84996-366-4 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2010933607 © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2011 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criti- cism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Hand Surgery: a Guide for Medical Students

Hand Surgery: A Guide for Medical Students Trevor Carroll and Margaret Jain MD Table of Contents Trigger Finger 3 Carpal Tunnel Syndrome 13 Basal Joint Arthritis 23 Ganglion Cyst 36 Scaphoid Fracture 43 Cubital Tunnel Syndrome 54 Low Ulnar Nerve Injury 64 Trigger Finger (stenosing tenosynovitis) • Anatomy and Mechanism of Injury • Risk Factors • Symptoms • Physical Exam • Classification • Treatments Trigger Finger: Anatomy and MOI (Thompson and Netter, p191) • The flexor tendons run within the synovial tendinous sheath in the finger • During flexion, the tendons contract, running underneath the pulley system • Overtime, the flexor tendons and/or the A1 pulley can get inflamed during finger flexion. • Occassionally, the flexor tendons and/or the A1 pulley abnormally thicken. This decreases the normal space between these structures necessary for the tendon to smoothly glide • In more severe cases, patients can have their fingers momentarily or permanently locked in flexion usually at the PIP joint (Trigger Finger‐OrthoInfo ) Trigger Finger: Risk Factors • Age: 40‐60 • Female > Male • Repetitive tasks may be related – Computers, machinery • Gout • Rheumatoid arthritis • Diabetes (poor prognostic sign) • Carpal tunnel syndrome (often concurrently) Trigger Finger: Subjective • C/O focal distal palm pain • Pain can radiate proximally in the palm and distally in finger • C/O finger locking, clicking, sticking—often worse during sleep or in the early morning • Sometimes “snapping” during flexion • Can improve throughout the day Trigger Finger: -

Rapid HTA Report Ultrasonic Energy Devices for Surgery July 2014

Rapid HTA report 1 Ultrasonic energy devices for surgery July 2014 1 This report should be cited as: Migliore A, Corio M, Perrini MR, Rivoiro C, Jefferson T. Ultrasonic energy devices for surgery: rapid HTA report. Agenas, Agenzia nazionale per i servizi sanitari regionali. Rome, July 2014. Contributions Authors Antonio Migliore, Mirella Corio, Maria Rosaria Perrini, Chiara Rivoiro, and Tom Jefferson Agenas, Agenzia nazionale per i servizi sanitari regionali, Area Funzionale Innovazione, Sperimentazione e Sviluppo, via Puglie 23, 00187 Rome (Italy) Corresponding author Antonio Migliore, MSc ([email protected]) Clinical experts Mario Alessiani, MD FACS Division of General Surgery, Varzi Hospital, University of Pavia (Italy) Marco Filauro, MD Division of General and Hepatobiliopancreatic Surgery, Galliera Hospital, Genova (Italy) Invited reviewers Chuong Ho, MD MSc Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa (Canada) Björn Fahlgren, MSc 2 Comité d’évaluation des technologies de santé (CEDIT), Paris (France) Acknowledgements Authors would like to thank Marina Cerbo (Agenas) and Simona Paone (Agenas), for the valuable help in reviewing the research protocol and the first draft of the report, Patrizia Brigoni (Agenas) for performing the systematic literature searches, Fabio Bernardini (Agenas) for his relevant support in retrieving the publications, and Laura Velardi (Agenas) for supporting consultation and analysis of databases. Declaration on the conflict of interest and privacy Authors, Clinical expert and External Reviewers declare that they do not receive benefits or harms from the publication of this report. None of the authors have or have held shares, consultancies or personal relationships with any of the producers of the devices assessed in this document.