HHS Public Access Author Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Long-Read Genome Sequencing for the Diagnosis Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.185447; this version posted September 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Long-read genome sequencing for the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders Susan M. Hiatt1, James M.J. Lawlor1, Lori H. Handley1, Ryne C. Ramaker1, Brianne B. Rogers1,2, E. Christopher Partridge1, Lori Beth Boston1, Melissa Williams1, Christopher B. Plott1, Jerry Jenkins1, David E. Gray1, James M. Holt1, Kevin M. Bowling1, E. Martina Bebin3, Jane Grimwood1, Jeremy Schmutz1, Gregory M. Cooper1* 1HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL, USA, 35806 2Department of Genetics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA, 35924 3Department of Neurology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA, 35924 *[email protected], 256-327-9490 Conflicts of Interest The authors all declare no conflicts of interest. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.02.185447; this version posted September 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Purpose Exome and genome sequencing have proven to be effective tools for the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), but large fractions of NDDs cannot be attributed to currently detectable genetic variation. This is likely, at least in part, a result of the fact that many genetic variants are difficult or impossible to detect through typical short-read sequencing approaches. -

Complete Loss of CASK Causes Severe Ataxia Through Cerebellar Degeneration

Complete loss of CASK causes severe ataxia through cerebellar degeneration Paras Patel Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC Julia Hegert Orlando Health Corp Ingrid Cristian Orlando Health Corp Alicia Kerr National Eye Institute Leslie LaConte Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC Michael Fox Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC Sarika Srivastava Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC Konark Mukherjee ( [email protected] ) Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6922-9554 Research article Keywords: CASK, MICPCH, neurodegeneration, X-linked, X-inactivation, cerebellum, ataxia Posted Date: May 4th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-456061/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/34 Abstract Background: Heterozygous loss of X-linked genes like CASK and MeCP2 (Rett syndrome) causes neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) in girls, while in boys loss of the only allele of these genes leads to profound encephalopathy. The cellular basis for these disorders remains unknown. CASK is presumed to work through the Tbr1-reelin pathway in neuronal migration. Methods: Here we report clinical and histopathological analysis of a deceased 2-month-old boy with a CASK-null mutation. We rst analyze in vivo data from the subject including genetic characterization, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) ndings, and spectral characteristics of the electroencephalogram (EEG). We next compare features of the cerebellum to an-age matched control. Based on this, we generate a murine model where CASK is completely deleted from post-migratory neurons in the cerebellum. Results: Although smaller, the CASK-null human brain exhibits normal lamination without defective neuronal differentiation, migration, or axonal guidance, excluding the role of reelin. -

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation from a Neurological Perspective

brain sciences Review Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation from a Neurological Perspective Justyna Paprocka 1,* , Aleksandra Jezela-Stanek 2 , Anna Tylki-Szyma´nska 3 and Stephanie Grunewald 4 1 Department of Pediatric Neurology, Faculty of Medical Science in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, 40-752 Katowice, Poland 2 Department of Genetics and Clinical Immunology, National Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, 01-138 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Pediatrics, Nutrition and Metabolic Diseases, The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, W 04-730 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 4 NIHR Biomedical Research Center (BRC), Metabolic Unit, Great Ormond Street Hospital and Institute of Child Health, University College London, London SE1 9RT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-606-415-888 Abstract: Most plasma proteins, cell membrane proteins and other proteins are glycoproteins with sugar chains attached to the polypeptide-glycans. Glycosylation is the main element of the post- translational transformation of most human proteins. Since glycosylation processes are necessary for many different biological processes, patients present a diverse spectrum of phenotypes and severity of symptoms. The most frequently observed neurological symptoms in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are: epilepsy, intellectual disability, myopathies, neuropathies and stroke-like episodes. Epilepsy is seen in many CDG subtypes and particularly present in the case of mutations -

De Novo Mutations in Epileptic Encephalopathies

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature12439 De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies Epi4K Consortium* & Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project* Epileptic encephalopathies are a devastating group of severe child- were found to be highly improbable (Table 1 and Fig. 1). We performed hood epilepsy disorders for which the cause is often unknown1.Here the same calculations on all of the genes with multiple de novo mutations we report a screen for de novo mutations in patients with two clas- observed in 610 control trios and found no genes with a significant excess sical epileptic encephalopathies: infantile spasms (n 5 149) and of de novo mutations (Supplementary Table 4). Although mutations in Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (n 5 115). We sequenced the exomes of GABRB3 have previously been reported in association with another type 264 probands, and their parents, and confirmed 329 de novo muta- of epilepsy15, and in vivo mouse studies suggest that GABRB3 haplo- tions. A likelihood analysis showed a significant excess of de novo insufficiency is one of the causes of epilepsy in Angelman’s syndrome16, mutations in the 4,000 genes that are the most intolerant to func- our observations implicate it, for the first time, as a single-gene cause of tional genetic variation in the human population (P 5 2.9 3 1023). epileptic encephalopathies and provide the strongest evidence to date for Among these are GABRB3,withde novo mutations in four patients, its association with any epilepsy. Likewise, ALG13, an X-linked gene and ALG13,withthesamede novo mutation in two patients; both encoding a subunit of the uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine genes show clear statistical evidence of association with epileptic transferase, was previously shown to carry a novel de novo mutation in encephalopathy. -

Nephrotoxicity of the BRAF-Kinase Inhibitor Vemurafenib Is Driven By

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.29.428783; this version posted January 31, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Nephrotoxicity of the BRAF-kinase inhibitor Vemurafenib is driven by off-target Ferrochelatase inhibition Yuntao Bai1, Ji Young Kim1, Laura A. Jayne1, Megha Gandhi1, Kevin M. Huang1, Josie A. Silvaroli1, Veronika Sander2, Jason Prosek3, Kenar D. Jhaveri4, Sharyn D. Baker1, Alex Sparreboom1, Amandeep Bajwa5, Navjot Singh Pabla1* 1Division of Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy & Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. 2Department of Molecular Medicine and Pathology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. 3The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA. 4Division of Kidney Diseases and Hypertension, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra-Northwell, Northwell Health, Great Neck, New York, USA. 5Transplant Research Institute, James D. Eason Transplant Institute, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN, USA. Running Title: Off-target mechanisms associated with vemurafenib nephrotoxicity. Correspondence should be addressed to: Navjot Pabla, Division of Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy and Cancer Center, 460 W 12th Ave, Columbus, OH 43221, USA. Phone: 614-292-1063. E-mail: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.29.428783; this version posted January 31, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Cldn19 Clic2 Clmp Cln3

NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation When time to diagnosis matters, the NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation from Athena Diagnostics delivers rapid, 5- to 7-day results on a targeted 1,722-genes. A2ML1 ALAD ATM CAV1 CLDN19 CTNS DOCK7 ETFB FOXC2 GLUL HOXC13 JAK3 AAAS ALAS2 ATP1A2 CBL CLIC2 CTRC DOCK8 ETFDH FOXE1 GLYCTK HOXD13 JUP AARS2 ALDH18A1 ATP1A3 CBS CLMP CTSA DOK7 ETHE1 FOXE3 GM2A HPD KANK1 AASS ALDH1A2 ATP2B3 CC2D2A CLN3 CTSD DOLK EVC FOXF1 GMPPA HPGD K ANSL1 ABAT ALDH3A2 ATP5A1 CCDC103 CLN5 CTSK DPAGT1 EVC2 FOXG1 GMPPB HPRT1 KAT6B ABCA12 ALDH4A1 ATP5E CCDC114 CLN6 CUBN DPM1 EXOC4 FOXH1 GNA11 HPSE2 KCNA2 ABCA3 ALDH5A1 ATP6AP2 CCDC151 CLN8 CUL4B DPM2 EXOSC3 FOXI1 GNAI3 HRAS KCNB1 ABCA4 ALDH7A1 ATP6V0A2 CCDC22 CLP1 CUL7 DPM3 EXPH5 FOXL2 GNAO1 HSD17B10 KCND2 ABCB11 ALDOA ATP6V1B1 CCDC39 CLPB CXCR4 DPP6 EYA1 FOXP1 GNAS HSD17B4 KCNE1 ABCB4 ALDOB ATP7A CCDC40 CLPP CYB5R3 DPYD EZH2 FOXP2 GNE HSD3B2 KCNE2 ABCB6 ALG1 ATP8A2 CCDC65 CNNM2 CYC1 DPYS F10 FOXP3 GNMT HSD3B7 KCNH2 ABCB7 ALG11 ATP8B1 CCDC78 CNTN1 CYP11B1 DRC1 F11 FOXRED1 GNPAT HSPD1 KCNH5 ABCC2 ALG12 ATPAF2 CCDC8 CNTNAP1 CYP11B2 DSC2 F13A1 FRAS1 GNPTAB HSPG2 KCNJ10 ABCC8 ALG13 ATR CCDC88C CNTNAP2 CYP17A1 DSG1 F13B FREM1 GNPTG HUWE1 KCNJ11 ABCC9 ALG14 ATRX CCND2 COA5 CYP1B1 DSP F2 FREM2 GNS HYDIN KCNJ13 ABCD3 ALG2 AUH CCNO COG1 CYP24A1 DST F5 FRMD7 GORAB HYLS1 KCNJ2 ABCD4 ALG3 B3GALNT2 CCS COG4 CYP26C1 DSTYK F7 FTCD GP1BA IBA57 KCNJ5 ABHD5 ALG6 B3GAT3 CCT5 COG5 CYP27A1 DTNA F8 FTO GP1BB ICK KCNJ8 ACAD8 ALG8 B3GLCT CD151 COG6 CYP27B1 DUOX2 F9 FUCA1 GP6 ICOS KCNK3 ACAD9 ALG9 -

Disease/Syndrome Features: Mutations in CDKL5 Are Associated

CDKL5 Disease/Syndrome Features: Mutations in CDKL5 are associated with early-onset, difficult to control seizures, X-linked intellectual disability, hypotonia, motor disability, and cortical visual impairment [Olson 2019]. Pathogenic variants in CDKL5 affect one in 40,000 to 60,000 live births with a female:male ratio of 4:1 [Olson 2019]. Individuals with mutations in CDKL5 show considerable phenotypic overlap with Rett syndrome, a disorder most often caused by mutations in MECP2, a gene also located on the X chromosome that is involved in transcriptional silencing and epigenetic regulation of methylated DNA. Features in common include a period of normal development followed by regression, minimal or absent speech, the inability to walk unassisted, hand stereotypies, breathing abnormalities, and autistic features. Infantile seizures are universal in CDKL5 disorders, and not typical of Rett. Individuals with CDKL5 mutations may also suffer from scoliosis, gastrointestinal difficulties, spasticity, hyperreflexia, and visual impairment. The full spectrum of CDKL5-related diseases is still being elucidated and mutations in the gene have so far been found in children previously diagnosed with Rett syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and autism spectrum disorders [Tao 2004, Weaving 2004]. In terms of neuroimaging, most case reports have documented normal brain anatomy or occasional cortical atrophy or T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities in the white matter [Olson 2019], however neuroimaging has not yet been systematically reported in affected individuals. With regard to neuropathology, a single case report described the brain as the solely affected organ in a postmortem examination [Paine 2012]. Findings included cortical and cerebellar atrophy, ventricular enlargement, cerebral cortical gliosis, neuronal heterotopias in the white matter of the cerebellar vermis, gliosis of cerebellar cortex with loss of Purkinje cells and axonal swellings, and perivascular lymphocytes and axonal swellings in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. -

Associated with Low Dehydrodolichol Diphosphate Synthase (DHDDS) Activity S

Sabry et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2016) 11:84 DOI 10.1186/s13023-016-0468-1 RESEARCH Open Access A case of fatal Type I congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG I) associated with low dehydrodolichol diphosphate synthase (DHDDS) activity S. Sabry1,2,3,4, S. Vuillaumier-Barrot1,2,5, E. Mintet1,2, M. Fasseu1,2, V. Valayannopoulos6, D. Héron7,8, N. Dorison8, C. Mignot7,8,9, N. Seta5,10, I. Chantret1,2, T. Dupré1,2,5 and S. E. H. Moore1,2* Abstract Background: Type I congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG-I) are mostly complex multisystemic diseases associated with hypoglycosylated serum glycoproteins. A subgroup harbour mutations in genes necessary for the biosynthesis of the dolichol-linked oligosaccharide (DLO) precursor that is essential for protein N-glycosylation. Here, our objective was to identify the molecular origins of disease in such a CDG-Ix patient presenting with axial hypotonia, peripheral hypertonia, enlarged liver, micropenis, cryptorchidism and sensorineural deafness associated with hypo glycosylated serum glycoproteins. Results: Targeted sequencing of DNA revealed a splice site mutation in intron 5 and a non-sense mutation in exon 4 of the dehydrodolichol diphosphate synthase gene (DHDDS). Skin biopsy fibroblasts derived from the patient revealed ~20 % residual DHDDS mRNA, ~35 % residual DHDDS activity, reduced dolichol-phosphate, truncated DLO and N-glycans, and an increased ratio of [2-3H]mannose labeled glycoprotein to [2-3H]mannose labeled DLO. Predicted truncated DHDDS transcripts did not complement rer2-deficient yeast. SiRNA-mediated down-regulation of DHDDS in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells largely mirrored the biochemical phenotype of cells from the patient. -

(CDKL5) Deficiency Disorder: Clinical Review

Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5) deficiency disorder: clinical review Heather E. Olson1 Scott T. Demarest2, Elia M. Pestana-Knight3, Lindsay C. Swanson1, Sumaiya Iqbal4,5, Dennis Lal4,6, Helen Leonard 7, J. Helen Cross8, Orrin Devinsky9, Tim A. Benke10 1 Department of Neurology, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Neurophysiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA 2 Children’s Hospital Colorado and Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado, School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA 3 Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute Epilepsy Center, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute Pediatric Neurology Department, Neurogenetics, Cleveland Clinic Children’s, Cleveland, OH. 4 Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA 5 Analytic and Translational Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA 6 Cleveland Clinic Genomic Medicine Institute and Neurological Institute, Cleveland, OH, US 7 Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia 8 UCL Great Ormond Street NIHR BRC Institute of Child Health, London, UK 9 Department of Neurology, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10 Children’s Hospital Colorado and Departments of Pediatrics, Pharmacology, Neurology and Otolaryngology, University of Colorado, School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA Corresponding author: Heather Olson, MD, MS Boston Children’s Hospital 300 Longwood Ave., Mailstop 3063 Boston, MA 02115 [email protected] Word count abstract: 146 Word count body: 3665 Abstract CDKL5 deficiency disorder (CDD) is a developmental encephalopathy caused by pathogenic variants in the gene cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5). This unique disorder includes early infantile onset refractory epilepsy, hypotonia, developmental intellectual and motor disabilities, and cortical visual impairment. -

Pharmacological Reactivation of Inactive X-Linked Mecp2 in Cerebral Cortical Neurons of Living Mice

Pharmacological reactivation of inactive X-linked Mecp2 in cerebral cortical neurons of living mice Piotr Przanowskia, Urszula Waskoa, Zeming Zhenga, Jun Yub, Robyn Shermana, Lihua Julie Zhub,c, Michael J. McConnella,d, Jogender Tushir-Singha, Michael R. Greenb,e,1, and Sanchita Bhatnagara,d,1 aDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908; bDepartment of Molecular, Cell and Cancer Biology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01605; cPrograms in Molecular Medicine and Bioinformatics and Integrative Biology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01605; dDepartment of Neuroscience, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908; and eHoward Hughes Medical Institute, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01605 Contributed by Michael R. Green, June 19, 2018 (sent for review March 2, 2018; reviewed by Aseem Z. Ansari and Sukesh R. Bhaumik) Rett syndrome (RTT) is a genetic disorder resulting from a loss-of- Although Xi-linked MECP2 reactivation has implications for function mutation in one copy of the X-linked gene methyl-CpG– the treatment of RTT, the approach has been hampered by a lack binding protein 2 (MECP2). Typical RTT patients are females and, due of complete understanding of the molecular mechanisms of XCI to random X chromosome inactivation (XCI), ∼50% of cells express and the key regulators involved. Recently, however, several large- mutant MECP2 and the other ∼50% express wild-type MECP2. Cells scale screens have identified factors involved in XCI and have expressing mutant MECP2 retain a wild-type copy of MECP2 on the yielded important mechanistic insights (9–11). -

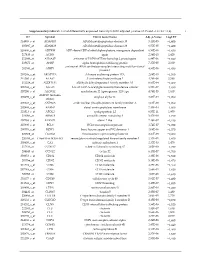

Supplementary Table S1. List of Differentially Expressed

Supplementary table S1. List of differentially expressed transcripts (FDR adjusted p‐value < 0.05 and −1.4 ≤ FC ≥1.4). 1 ID Symbol Entrez Gene Name Adj. p‐Value Log2 FC 214895_s_at ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 3,11E‐05 −1,400 205997_at ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 6,57E‐05 −1,400 220606_s_at ADPRM ADP‐ribose/CDP‐alcohol diphosphatase, manganese dependent 6,50E‐06 −1,430 217410_at AGRN agrin 2,34E‐10 1,420 212980_at AHSA2P activator of HSP90 ATPase homolog 2, pseudogene 6,44E‐06 −1,920 219672_at AHSP alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein 7,27E‐05 2,330 aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex interacting multifunctional 202541_at AIMP1 4,91E‐06 −1,830 protein 1 210269_s_at AKAP17A A‐kinase anchoring protein 17A 2,64E‐10 −1,560 211560_s_at ALAS2 5ʹ‐aminolevulinate synthase 2 4,28E‐06 3,560 212224_at ALDH1A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 8,93E‐04 −1,400 205583_s_at ALG13 ALG13 UDP‐N‐acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit 9,50E‐07 −1,430 207206_s_at ALOX12 arachidonate 12‐lipoxygenase, 12S type 4,76E‐05 1,630 AMY1C (includes 208498_s_at amylase alpha 1C 3,83E‐05 −1,700 others) 201043_s_at ANP32A acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family member A 5,61E‐09 −1,760 202888_s_at ANPEP alanyl aminopeptidase, membrane 7,40E‐04 −1,600 221013_s_at APOL2 apolipoprotein L2 6,57E‐11 1,600 219094_at ARMC8 armadillo repeat containing 8 3,47E‐08 −1,710 207798_s_at ATXN2L ataxin 2 like 2,16E‐07 −1,410 215990_s_at BCL6 BCL6 transcription repressor 1,74E‐07 −1,700 200776_s_at BZW1 basic leucine zipper and W2 domains 1 1,09E‐06 −1,570 222309_at -

Characterization of X-Linked SNP Genotypic Variation in Globally Distributed Human Populations Genome Biology 2010, 11:R10

Casto et al. Genome Biology 2010, 11:R10 http://genomebiology.com/2010/11/1/R10 RESEARCH Open Access CharacterizationResearch of X-Linked SNP genotypic variation in globally distributed human populations Amanda M Casto*1, Jun Z Li2, Devin Absher3, Richard Myers3, Sohini Ramachandran4 and Marcus W Feldman5 HumanAnhumanulation analysis structurepopulationsX-linked of X-linked variationand provides de geneticmographic insights variation patterns. into in pop- Abstract Background: The transmission pattern of the human X chromosome reduces its population size relative to the autosomes, subjects it to disproportionate influence by female demography, and leaves X-linked mutations exposed to selection in males. As a result, the analysis of X-linked genomic variation can provide insights into the influence of demography and selection on the human genome. Here we characterize the genomic variation represented by 16,297 X-linked SNPs genotyped in the CEPH human genome diversity project samples. Results: We found that X chromosomes tend to be more differentiated between human populations than autosomes, with several notable exceptions. Comparisons between genetically distant populations also showed an excess of X- linked SNPs with large allele frequency differences. Combining information about these SNPs with results from tests designed to detect selective sweeps, we identified two regions that were clear outliers from the rest of the X chromosome for haplotype structure and allele frequency distribution. We were also able to more precisely define the geographical extent of some previously described X-linked selective sweeps. Conclusions: The relationship between male and female demographic histories is likely to be complex as evidence supporting different conclusions can be found in the same dataset.